published: 23 /

12 /

2021

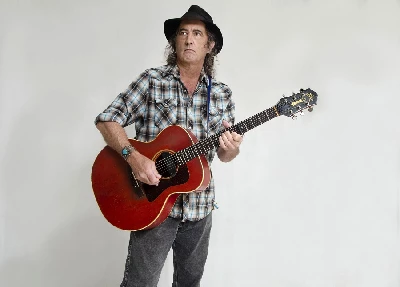

Austin, Texan singer-songwriter James McMurtry talks to Lisa Torem about his first album,in six years ‘The Horses and The Hounds’, and songcraft, politics, early influences and why he never could play like Johnny Cash.

Article

By phone from Austin, Texas, James McMurtry makes the best out of a maddening year: “I don’t mind staying home and streaming from my kitchen table. My back doesn’t hurt as much. We’re starting to play out a little more. We hit Houston and Dallas over the weekend. It’s the first indoor shows we’ve done as a band since 2020.”

In many ways, the Texas-based, Virginia-raised singer-songwriter-guitarist exemplifies the endearing but hard-scrabble characters he creates: hard-working, resilient, communicative people who rise above adversity in real time, but don’t require fanfare.

A seeker whose suitcase gathers no dust, McMurtry studied Spanish at the University of Tucson, busked in Alaska and painted houses in San Antonio, when he wasn’t tending bar or competing for stage time at open mics. Conversations, perhaps from those years, and certainly beyond, colour his guitar-driven crusades.

Fans have waited six years to hear McMurtry’s new album, ‘The Horses and the Hounds,’ the follow-up to 2015’s ‘Complicated Game’. The Russ Hogarth-produced project was recorded at Jackson Browne’s Groovemasters Studios and includes guest guitarist Dave Grissom and drummer Kenny Aronoff. McMurtry’s matter-of-fact demeanor and grinding guitar work was tastefully enhanced by strings and quality microphones.

Of course, McMurtry is no stranger to the studio. John Mellencamp co-produced his debut studio project, ‘Too Long in the Wasteland’, there back in 1989. Between 1992 and 2002, he recorded four more studio albums. In the spring of 2004, ‘Live in Aught-Three’ featured ‘Choctaw Bingo,’ which also appeared on ‘St. Mary of the Woods.’ It’s one of his signature songs; rife with struggling characters, a bustling casino, addictive drugs, you name it. And it’s got an irresistible beat.

In 2005, McMurtry made a name for himself in Nashville, when ‘Childish Things’ won at the 5th Annual Americana Music Awards. ‘We Can’t Make It Here’ spoke to disillusioned working-class people, and pointed fingers at unjust politicians.

Three years later, ‘Just Us Kids’ included songs targeting the policies of American president George W. Bush, along with songs that examined human emotions and places that most of us might overlook, but where McMurtry discovers austere beauty.

‘The Horses and The Hounds’ has elements of albums past, but the session musicians, clean production and unexpected reveals make it a stunner. McMurtry is still a keen observer of life; society’s limitations and small, unexpected pleasures. But it’s not only the exemplary meter and structure that’s evident here; it’s also that this unique songwriter seems more open than ever.

In this Pennyblackmusic interview, James McMurtry talks songcraft, politics, early influences and why he never could play like Johnny Cash.

PB: Congratulations on ‘The Horses and the Hounds’. You don’t generally collaborate as a songwriter. Do you simply prefer writing solo?

JM: I like the result better solo. I used to write with Fred Koller in Nashville back in the 1980s. We wrote things that sounded like songs and usually that was okay for Nashville at the time but a lot of the songs we got recorded were not really complete songs.

I never got lucky in that vein. I can take an idea or line and build a song around it and somebody gets a writer credit if they gave me the line, but I’ve never been able to bat ideas back and forth and come up with anything I liked.

Fred Koller co-wrote hits for Kathy Mattea and co-wrote with Shel Silverstein. He wrote with everybody. He and John Prine wrote a song, ‘Let’s Talk Dirty in Hawaiian’ which John Prine used to do a lot on his shows.

‘Complicated Game’ was not so much that way. I did it piecemeal over every year but this one I had Russ Hogarth producing. We had to juggle our schedules to make it happen because Russ is pretty busy.

PB: Do you ever get ideas from a newspaper article or a dream?

JM: I’ll hear something in my head accidently and that’s the seed. I’ll start with that.

PB: And that’s a phrase, not a melody?

JM: I get the melody and the line at the same time.

PB: Who are your favorite songwriters?

JM: The first artist who was identified to me as a songwriter was Kris Kristofferson. I always like his stuff. He wrote a very tight verse. He was a Rhodes Scholar. He studied the art. All of his syllables fall in the pocket. He can sing them or talk them with both equal results. So, Kristofferson, Prine, and much later, Tom Petty. Tom Petty wrote little bitty songs that got to be great big hits. That was really cool.

PB: Your father, Larry McMurtry wrote prose; you write lyrics. Can you envision your songs becoming short stories or outlines for novels?

JM: If somebody wants to write them, yeah. I don’t like to write prose; I find it a chore.

PB: Are there songs that you could imagine being expanded upon?

JM: ‘Ruby and Carlos.’ A lot of them are story-songs. You could definitely flesh them out.

PB: If you could have a drink or meal with one of your characters, which one would you choose?

JM: Probably Ruby.

PB: Why?

JM: I don’t know. She’s a tough woman.

PB: Speaking of “tough women,” what goes through your mind when you write from a female character’s point-of-view? Do you do a reality check with women you know?

JM: I just make it up. It might not be accurate, but I follow the lines.

PB: Two big requests when you perform live are ‘Choctaw Bingo’ and “You Can’t Make it Here.’ On those songs, there is a focus on the community at large. On ‘The Horses and the Hounds’ album, the focus seems to be more reflective and introspective. Did you consciously change your approach to writing for this album project?

JM: No, I’ve never changed my approach. I start with a couple of lines and I try to figure out who said those lines so I can get a character and maybe get a story. I didn’t consciously change any kind of focus but when I make a record, I record whatever songs I finish in time.

PB: So, you’re deadline-driven?

JM: Usually, yeah.

PB: Percussionist Kenny Aronoff guested on the album. He worked from 1980-1996 with one of your colleagues John Mellencamp. Kenny’s beats add a lot to your arrangements. Did you speak with Kenny about the sound you wanted to achieve on this record?

JM: No. He was brought in later for percussion. He did hand drums. And I really had no input. He and Russ did that in L.A. during the lockdown in 2020, I guess. It might have been earlier than lockdown, but I was not there for those sessions. Kenny emailed those parts to Russ and Russ edited out whatever he wanted.

PB: How long did it take to complete ‘The Horses and the Hounds’?

JM: Well, we tracked in June of 2019 and I think the final mixes were done in late 2020. We were just about to do keyboard overdubs when we had a session booked at Sunset Sound in March, 2020. Then, L.A. shut down. We couldn’t do it. So, it took a while to get the rest of the keyboards done—various places with various players.

PB: Some of your songs are rooted in specific places. To what degree do those places and the cultures there inspire your lyrics?

JM: I don’t know. I happen to see something through a windshield usually. I connect the details. I look everywhere for a song. If it happens to be in Maryland, then the song is set in Maryland, that sort of thing.

PB: I’d like you to comment on specific tracks. Let’s start with ‘Canola Fields.’ Here,

you juxtapose a beautiful landscape with memories of an old girlfriend. It’s urban and anachronistic. ‘We met up in Brooklyn before it went hipster.’ You appear to value long-term love here: ‘Cashing in on a thirty-year crush. You can’t be young and do that.’ What was the back story?

JM: That song came in pieces. I don’t know how I had that original, but I started with the line about the ‘second best surfer on the central coast.’ So, I had part of it set around Santa Cruz, San Jose.

Then, we spent time touring back and forth across Western Canada and there’s this crop that glows in the sun that makes this incredible chartreuse blossom and we didn’t know what it was. Then, we go through there in the fall and through the window, it looks like tumbleweeds raked up. And they had these weird machines going up and scooping up the rows and spitting chaff out the back.

Finally, we came to an empty field with a big sign and it said, ‘Canola Processing’ with a phone number. That’s how we knew it was ‘Canola.’ And somehow, I connected that with the color of some of those old Volkswagens that were painted in that bright chartreuse. I got the pieces over the years and just stuck them together.

PB: ‘Operation Never Mind’ feels like a wakeup call to complacent Americans. You don’t shy away from writing controversial lyrics. Has this always been the case or more so lately?

JM: ‘We Can’t Make it Here’ was kind of in your face. I got some of the story from a friend of mine who was in the army for a long time. He watched it change and become more privatized, but part of what bothers me about the American Military Organization is the lack of coverage since Vietnam.

We haven’t had that kind of war coverage. The last time I saw journalists walking around interviewing random servicemen was with the Marines in Beirut. The crews were walking up to these Marines and the Marines were allowed to talk. They were looking straight into the camera and saying, ‘Why did you send us to this mission? We’re an offensively trained unit but you got us sitting around at an airport getting shot at because we’re on high ground and we can’t go out and take the high ground and this is not our mission.’

Shortly after that, somebody drove a truck bomb into the barracks and killed about 360 guys. Weinberger (secretary of defense) and Reagan (Ronald Reagan, 40th U.S. President) didn’t look good. Suddenly, in a matter of weeks, we’re invading the tiny island of Grenada, by Trinidad in the Caribbean, and nobody really knows why. They said there was a 12,000-foot roadway that they were building.

Mike Royko, from the Chicago Tribune at that time, he simply called up the British architectural firm that designed the airport and asked, “Hey, is that a military airport?” and they said, “No, the military would have more than one runway so you can send jets in different directions at the same time.”

So, obviously they were building a big runway so they could land DC10s and 747s. Reagan decided to invade. It was obvious, to me, that it was mostly to take their minds off of the fiasco in Beirut and have something he could call good news, but it went a little further. There were two journalists that went ashore with U.S. forces As soon as they got ashore, they were immediately arrested, detained and taken back out to the aircraft carrier. The only journalists who got on the island snuck in with Grenadian civilians coming in from Barbados. That’s what

ended the first amendment with regard to war coverage and we never got it back.

During Desert Storm, we had General Schwarzkopf in a tent, spoon feeding the war to the press pool, with the video clips that he wanted us to see and we have embeds that thought they were doing pretty good journalism but they have to pick the units that they’re embedded with so they’re not giving a clear picture and you have to dig for that stuff; it’s not a media splurge.

Back in Vietnam, we had Walter Cronkite, and a couple of other people that were trying to be

Walter Cronkite and everybody listened to that, so there was a central voice for the nation but when cable air took off, suddenly everybody had their own news show to tell them what they’re already thinking and nobody is really out there reporting because they’re not allowed to, so that’s part of the chorus: “No one knows cause no one sees it on TV.” Instead, we have very well-scripted and well-acted dramas but they’re recreations.

PB: ‘Jackie’ is a woman who tends judiciously to her horse ranch. She comes across, to me, as a no-nonsense person, but the instrumental arrangement feels very dreamy. There’s that juxtaposition. How did you come to that decision?

JM: I didn’t. I didn’t produce this record. Russ stuck the cellos in there. It seemed to work.

PB: You’ve got great rhymes in there: “She jack-knifed on black ice.” You mastered the meter.

JM: That was actually two songs. Once again, I had pieces. I was scrolling through my hard drive. I took my notes out. I had something about “jack-knife” and “black ice” and I had something about “Jackie” and realized I had kept the same line and rhyme scheme and that’s when ‘’Jackie’ became a trucker. Originally, the trucker was male.

PB: Were you ever a trucker?

JM: No, I’d never go near an 18-wheeler.

PB: ‘Decent Man’ was inspired by a Wendell Berry short story. You condensed your observations into a single song.

JM: No, I just changed the point-of-view and the chamber of the pistol. That’s about it. And the season of the year. In the Wendell story, it was mid-summer, real hot.

PB: The title song, ‘The Horses and the Hounds,’ to me, is about escape, when there is no way to escape without looking in the mirror.

JM: It’s just about internal demons, to me. The listener can take whatever he wants from it. The cool thing about songs--they’re very sparse, so the listener can maybe hear himself in it.

PB: In ‘Ft. Walton Wake-Up Call,’ you have the line, “I keep losing my glasses” which you have said in interviews was pretty much a placeholder, yet the line brings to mind the ‘third act’, perhaps looking back at life with humor and a certain degree of resolve. Despite your intentions, the line seems to have created a life all its own.

JM: I just heard it in my head and I needed something to indicate that there would be lyrics in that spot. I didn’t think anything about the meaning of it. I just put it in there and played it at soundcheck a couple of times and the guys thought it was fine. “You don’t need to change that—it worked.” I just left it in because it didn’t bother anybody.

PB: ‘What’s the Matter’ is a very human song that I believe will strike home for many musicians and their partners: “I know, it ain’t healthy but this is what I do. Same thing I was doing before I met you.” Has juggling a career with a domestic life been a challenge?

JM: Well, it sure is for everybody. But I do most of the driving, so for decades, I was driving along listening to guys walking around on cell phones. And as soon as we leave town, everybody’s washing machine would break, or something would go wrong that they would normally fix themselves if they were home, but they can’t.

PB: There’s a sense that the partner wants more of you, but you’re not there to give it.

JM: Yeah, but that’s not unique to a music career; probably any career would do that.

PB: In ‘Blackberry Winter,’ a line is: “I don’t pick up signs like I ought to.” It’s true that we don’t always recognise other points of view or feelings which leads to poor communication. Did anything in particular trigger that insight?

JM: I think I was trying to rhyme something with “bought you.” I think, the “bought you” came first and I rhymed “ought to” just so it would rhyme.

PB: Did you study poetry? Did your parents read poetry to you when you were growing up?

JM: I studied it a little bit in high school and college. I thought poetry would be an elective I would need, but I never did graduate anyway. But I put it to practice.

PB: Can you tell me about your guitar playing?

JM: I play 12 and six and I actually have an eight-string baritone. It’s the same. The only difference with a 12 string is double strings, where you’re pressing down two strings at a time and every note is a chord; some are octaves; split. But you have to play a little different; you have to slow down. The number of strings doesn’t matter so much but I do use a lot of drop tunings just to get more low end.

PB: How did you learn to play?

JM: My mother taught me three or four chords when I was about seven-years-old and I just kept doing it until my fingers would find note for note, because I didn’t know where they were to start with. Sometimes I might hear somebody do something and I’d copy it. Just like anybody, you know?

PB: Who did you try to imitate?

JM: I guess Luther Perkins very early on, because I was a big Johnny Cash fan, but I didn’t have a Telecaster so I couldn’t really do that palm mute thing like you hear.

PB: You have a distinctive style.

JM: I can’t really play like anybody else. I can only play like me.

PB: I saw you perform in Chicago at Old Town School last time you were here. I got the impression that most of the audience knows most of your songs. Does that make it easier for you to perform or does it put you under more pressure?

JM: It probably makes it easier to connect. It is interesting playing brand new stuff that they’ve never heard. It’s a little more challenging.

PB: Do you have any advice for new acts that want to do original music?

JM: Quit if you can. Those who can’t quit might make it.

PB: Thank you.

Photos by Mary Keating-Bruton

Band Links:-

https://www.jamesmcmurtry.com/

https://www.facebook.com/JamesMcMurtry

https://twitter.com/jamesmcmurtry

Play in YouTube:-

Have a Listen:-

Picture Gallery:-