Beat

-

Interview

published: 23 /

2 /

2020

Frontman Dave Wakeling reminisces on the 40th anniversary of the Beat’s fiery debut ‘I Can’t Help It’ and updates Lisa Torem about the band’s ambitious 2020 tour.

Article

Everything about Dave Wakeling screams music. His vocal inflexion is as animated over the phone as it is on stage. As far as street cred goes, Dave's is as impressive as the fruit salad on an admiral's jacket.

Hailing from Birmingham UK, a town with rich, multi-cultural musical roots, Dave began his career in the late 1970s as part of ska band The Beat. The Beat's 'I Just Can't Stop It' struck gold, featuring hits such as 'Mirror in the Bathroom,' 'Hands Off She's Mine' and 'Can't Get Used to Losing You.' With that last song in mind, Dave has a way of pumping new life into standards of ages past.

Sadly, his dear friend and bandmate, Ranking Roger, recently passed away. In 1984, they formed General Public; within half-a-year, they appeared on Top of the Pops. During their time together, they recorded 'All The Rage,' 'Hand to Mouth' and 'Rub It Better' before dissolving in the mid-90s.

Besides performing regularly as frontman and songwriter for the Beat, Dave has scored multiple films; an unsurprising move as his lyrics are rife with imagery.

There's nothing quite like seeing Dave and the Beat, or the English Beat, as they are called in North America, live. No one with a pulse can sit still during their shows. Skipping rhythms, blasting horns, intrepid riffs and climactic vocal incantations burst forward like a fireworks display.

In his second Pennyblackmusic interview, Dave talks about "two-tone" history, touring, Ranking Roger and discovering his Neanderthal roots.

PB: Hi, Dave. You're celebrating the 40th anniversary of 'I Just Can't Stop It'. What memories do you have of creating music for your debut?

DW: There was something charmed about the whole thing, the way the band came together. It was almost like drawing a cartoon of wanting to be in a pop group. We rehearsed, but not for very long. We started doing shows, and The Specials came and offered us more gigs, then they offered us a single. Within 12 months of us starting, we were number six in the charts. The album was recorded with that sort of attitude. We kind of felt unbeatable.

We didn't actually know much about what we were doing. Luckily, Bob Sargeant, our producer – he'd spent afternoons with most punk bands over the last five years, trying to get three songs out of them, so we got amazing studio discipline without knowing it. He just kept you working until it was as good as it could get.

It's a very fast record (laughs). People put it on the record player and think it was on the wrong speed. But we were young and enthusiastic and fueled.

It was also an interesting time because most of the major record labels had egg on their faces from having missed punk. The record companies were keen not to miss anything again. You'd have a dancehall full of people at your gigs, and they'd be terribly eager to sign you. Because of that, nobody ever mentioned anything about lyrics or politics or mixing the two. Not once did anybody from the record label say anything about 'Stand Down, Margaret'. They didn't even say anything when we released it as a single and donated all the money to anti-nuclear campaigns. There were no complaints about it. I don't know if they were more tolerant times; I don't think they were.

PB: Fans have many great memories of the charismatic Rankin' Roger who died last year. What were the onstage highlights of working with him? Your original song, 'Never Die' ('Here We Go Love') stands as a beautiful tribute. What thoughts and memories of Roger drift through your mind when you perform 'Never Die'?

DW: It was written over a number of years. It was based on several different people: my father's death, my mother's death, my older son's near-death experience and then Roger. It's a sort of tapestry of loss and grief.

Roger's was much more surprising than the other deaths because he was the baby and he always looked as fit as a fiddle. I used to worry about him a bit, and I told him about it. Sometimes when he came on stage, he and his audience seemed to be acting as if they were about twenty, as if they were recreating the '80s. Well, that's all well and good, but it's not safe to pretend you're 20 when you're 50.

That worried me a bit. The last few times I saw him, he didn't look very well, and I asked him if he'd had his thyroid checked because he looked so skinny.

He'd say, "Oh, no, no. I'm fine. Just working too much." But it did turn out, I would imagine from the details of his death, that he'd been sick for years. It's not something that would have developed the way it had within a short space of time. Of course, if you only see somebody every now and then, you notice it more, don't you?

I never kind of understood how he got missed in England. It's slightly different in England than in America. People don't go to doctors that much. "Oh, I'm fine. I'm fine." Perhaps he told them what he told me.

PB: 'Mirror in the Bathroom' is still heard all the time on TV and on soundtracks. What inspired the song?

DW: Well, David Steele's incredible music was a big part of it and the tempo, the signature of the song, is in 2/2, not 4/4. (Dave counts manically to reenact the beat) so there's this foreboding sense that something is happening.

The lyrics came about in somewhat of a hangover. I was working at a construction site. I'd forgotten to hang my clothes up that night, so I came in, and the jeans were still wet up to the knee. I had to put them back on to get to work. They were cold, snowy, itchy, Chicago-y so I took a shower and tried to warm them in the bathroom in the cold. I thought: I'll steam them, at least they'll be more comfortable. I left them steaming and tried to warm up the bathroom, and I started talking to myself, feeling very sorry for myself.

"We don't have to go to work. It's just me and you here." I was having a shave and talking in the mirror. I could actually see the lock of the door in the mirror as I was talking to myself. I did have to go to work. For one thing, we needed more guineas for that evening, so to work we went, and I couldn't get that poem out of my head.

It started to develop into this sense I had that the more people were fixated on themselves, the lonelier they felt. There is much in our society that encouraged that. People obsess on themselves and feel socially limited.

So I started thinking about that. Often with the songs, on the second verse, there are things I've seen in other people that reinforce that feeling. Then the third verse seemed to sum it up.

Punk can be sort of egocentric. People would really dress up and just stand there like a statue, looking gorgeous. But that was kind of tongue and cheek. It was more generally what I saw through society and the way that people were so wrapped up in themselves. It was difficult to reach out and touch.

PB: With both The Beat and General Public, you performed and recorded great originals, but also enjoyed success with cover tunes, 'Tears of a Clown' and 'I'll Take You There,' two American ballads. Can you choose one of those covers and tell us what intrigued you enough to want to create a new arrangement?

DW: Well, I suppose because I like syncopated or reggae beats—does it work well with that off-beat? 'Tears of a Clown' is a funny story because we'd started practising and sometimes it would sound fantastic just for a minute or two, or we'd veer off into our own style, or it would fade away.

Then Everett, the drummer, said: "Why don't we practice a song that we already know? When we've got that one tight, we can practice one of your weird ones." It took us about ten minutes to find one that we all actually knew. 'Tears of a Clown' was that song. We knew the chorus, but on our first version of it on the John Peel Show, we didn't bother with any of the difficult chords (Laughs). We just played all of the easy chords.

So anyway, we'd practice 'Mirror in the Bathroom', then 'Tears of a Clown'. Then 'Click Click', then 'Tears of a Clown'. Then 'Twist and Crawl' and 'Tears of a Clown', so in rehearsal, we practised 'Tears of a Clown' five or six times more than anything else. So we stuck it in the set because we'd only got eight songs and we needed nine.

At first gigs, you take whatever gig you can get. Sometimes they were punky shows, sometimes reggae, sometimes a factory Christmas party for old-age pensioners. Sometimes the different styles of our songs would go down better. 'Tears of a Clown' went down great everywhere we went: black, white, young, old.

In October, Jerry Dammers of The Specials, said: "Would you like to make a single for Two-Tone?" We presumed it would be, 'Mirror in the Bathroom', but Chrysalis Records jumped in and said: "Whichever song that is, you can't have it on your album because we own it for five years." We begged and begged and begged, but they wouldn't let it on.

In many ways, it was a much better choice because it came out in October and by December it was number six in the singles chart. Half of our friends despised us for that.

In many ways, that version of 'Tears of a Clown' was a much happier tune to have as a Christmas party song. Whereas 'Mirror in the Bathroom'?... Hi, thinking about having a nervous breakdown? Here's a brand new song.

PB: You'll be kicking off your upcoming UK tour with dates on the US coasts, then you'll be off to Brighton (June 3) and ending in Bristol (July 10). What can fans expect from this tour?

DW: Well, I've been going every year for the last four or five years. I didn't go last year out of respect for Roger's passing. As far as Birmingham, you'd expect there'd be a lot of conversations about Roger since he died. So that will be kind of bittersweet.

It's the anniversary tour of the first album and the forming of the band. It was quite a year for Roger. We'll be playing quite a lot of the first album, and there was some talk of playing them all in the same order of the recording. We've been through different things at different concerts. I don't know if it's appropriate, but we'll play most of the first album, not all of it, and we'll also play a couple of General Public hits. Though they were hits in England, they've become very popular over the years in the US since they've become standards. We'll play 'Tenderness' probably and 'I'll Take You There.'

PB: You've used alternative tuning in your repertoire. How does that process work? In other words, do you decide to use alternative tuning and then proceed to write? Or is it the other way around?

DW: Well, I wish I was in control of that. My dad gave me an acoustic guitar when I was 12, and neither of us knew how to play it. I was very confused by my posters of Jimi Hendrix and Paul McCartney. I thought that was the way you held it. So for three years, I played the guitar – unbeknownst to me – upside down. I had no idea, but it seemed right to me.

The hand on the fretboard with the funny shapes you have to make was difficult, whereas the other hand, strum, strum, strum— that seemed pretty easy, so I played with that one.

I bought a Rolling Stones and a Beatles songbook. After two years, I gave up. I couldn't play a bloody thing. So I tuned the guitar up to something that I thought sounded nice and just kept playing up and down with barre chords and added a finger here or there and created my own chords – so I thought.

I had tuned my guitar to Keith Richards' "G" tuning that he used in the Rolling Stones. Once I realised that, all of a sudden I could play Rolling Stones rock in the songbooks and that was good.

I played most of the songs on the first album, and sometimes on the second and third album, with that tuning. There are some songs on the third album that are played with proper tuning.

I tried to play along with John Martyn, and I couldn't. I tuned my guitar to what sounded about right on the John Martyn record, 'Solid Air'; and he used a tuning called BADGAD, which is in blues as well, but I tuned the G string up to an A, so it was all D's and A's. Someone told me that's a bagpipe tuning.

I thought about writing my own songs on that tuning. 'Save it for Later' came out of that. Also, the ballad, 'Never Die', that's with that tuning. So I made that one up entirely.

Many years later, Pete Townshend called me up on a Saturday morning, which was shocking in itself. He was sitting there with Dave Gilmour. They were trying to play 'Save it for Later', but they couldn't work out the tuning. So I had to tell my two guitar heroes from my childhood the key. One-finger wonder Wakeling.

I wish I could be more scientific, but I would just tune the guitar until something sounded nice.

PB: How would you define the genre Two-Tone for neophytes?

DW: Two-tone was a mixture of the energy of punk and the sinuous backbeat of ska. So it was like a fast, punky reggae and there was much in common between punk and reggae fans. They were both kind of banned from pubs (laughs).

They were outlaws, and like outlaws, they stuck together. You'd often have reggae bands playing at a punk show, not just The Specials in Coventry. There was a punky, reggae DJ roadshow that was on in London with The Slits and Don Letts.

We found there was another band in Coventry that were doing what we were doing – the Specials. It was as much social as it was musical. What was always interesting, to me, was the black and white checkerboard.

The police wore and still wear a checkered pattern around their hats in England. The police, punks and rastas were not the greatest friends at that time – they often met at demonstrations. I thought two-tone using that banner, grabbing the flag of the authorities and waving it back at them, would have been a much deeper and stronger message about black and white unity.

Whether that was intentional – it was the Specials who did that – I have no idea. That's what I took from it at the time. It was a remarkable thing because it wasn't in a vacuum. We grew up at a time when shadowy rightwing figures were recruiting disaffecting working class at central ball games and soccer games. Taking them away to Outward Bound weekends which turned out to be training courses for the British Movement and the National Front, which were very popular with the ultra-rightwing.

So there were these people fermenting trouble within these two communities. The skinheads on the side of decency were fighting back, and two-tone became the soundtrack. Anyway, it didn't need to make a big political treatise. If you've got a roomful of black and white people dancing together wearing the same clothes, even the same style of clothes, it was difficult to kick off a race war the following Monday. It took the steam out of the situation. It did make a huge mark at the time.

I always dreamt of being in a pop group. If I was, it'd be like the Monkees or the Beatles, and I'd get to be John Lennon. I'd get to write crafty things that would be all over the radio a year before anybody spotted it and my dream came true.

PB: Given your reign as a two-tone triathlete, what advice can you spare for rising artists?

DW: Mean it so much it makes you laugh and cry at the same time. You just can't stop doing it. In my opinion – and it's probably not necessarily true – there's a lot of professional songwriters that write from an objective point of view and probably do just as well. But for me, I have to find something that I'm incredibly passionate about.

Quite often a song starts because I'm thinking about something and it just gets to me. I'll start walking or pacing around, and my thoughts start turning into patterns. I start rhyming, and I usually take that as a sign. Got one on the hook here, mate. Got a fish on the line.

Then I just keep it in my head for ages, walk and pace and dance, and lots of ideas and images come through. It quite often starts off as a poem. It's got its own meter to it. It starts to shift from poetry into a song; I usually find where the key is then. I have to rush and get a guitar and go, "dum dum dum dum…" There it is, that's the one. I always think it's going to be terribly original, and it's usually G, C or D. You've done it again, Dave – playing three bloody chords.

PB: So much of your repertoire is memorable, in part, because of the bass lines.

DW: Well, David Steele's case kind of was the Mozart of the bass, a taciturn genius of the time and very affable. He started playing things on the bass guitar that none of us had ever heard of before. The first band that he'd been in had two bass players and a drummer. One bass player played really low and he would play the melodies really high. When we would start rehearsing, he would start out with a typical bass guitar line, and about three minutes in, he would play the melody. We had to sort that so he could keep the bass going. He went on to be the genius behind the Fine Young Cannibals as well, a talented lad.

On some songs, we would just let him come up with a bass line, and it was our job to figure the rest out. Other times, the bassline could come quite a long way into the songs; the other instruments are making a dominating pulse, and all of a sudden, the bassline appears. It worked in different ways, really.

PB: Given the opportunity, what power would you request from the universe?

DW: Even if you're a force for good, you're changing things, and if there's any change in balance in the world, the good that you've done is going to be balanced out with some bad elsewhere. You'd have to be really very careful with superpowers.

I fancy a happy eternity. I'd like to live forever and be able to help people in ad hoc places. Have the sort of superpowers that will actually help somebody. That actually makes a difference to them, as well as to me.

I always wanted to be Thor. I'm one-per cent Finnish. That's really not much, I'm mainly Anglo-Saxon from northern Germany. I did that 23andMe DNA test, and I'm in the top ten per cent of people in terms of Neanderthal DNA. I've got 308 and 380 is the top. So it turns out I was not quite Thor, but I've always found I've had trouble getting on with people. Perhaps I just have a problem with homo sapiens.

I'm a Neanderthal socialist. All I want to do is go out, kill a dear, cook it on a big bonfire, share it with my friends, have sex and go to sleep. I find it very, very difficult to achieve that in this society.

PB: There's always tomorrow, Dave. Thank you.

Band Links:-

http://englishbeat.net/

https://www.facebook.com/EnglishBeatFa

https://twitter.com/theenglishbeat

Play in YouTube:-

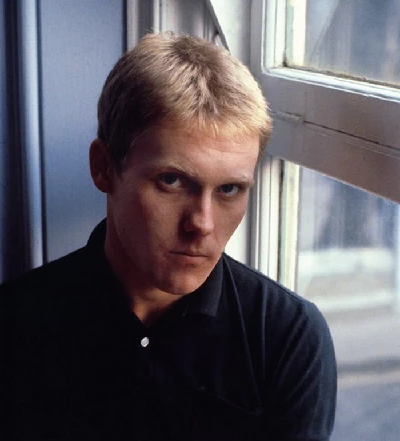

Picture Gallery:-