published: 24 /

12 /

2018

Drummer Woody Woodmansey speaks to Lisa Torem about Holy Holy’s upcoming UK tour, his compelling memoir and working in the studio with David Bowie.

Article

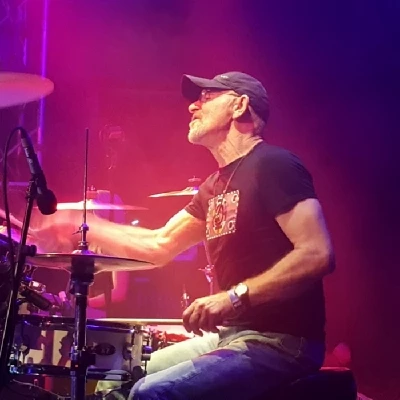

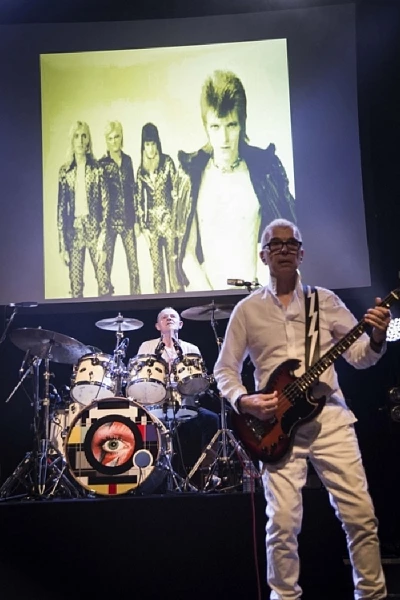

Drummer/author Woody Woodmansey is the last surviving member of The Spiders from Mars, David Bowie’s original backing band, which also consisted of guitarist Mick Ronson and bassist Trevor Bolder and brought Bowie to fame. Between 1970 and 1973, Woody served as drummer on the following related albums: ‘The Man Who Sold the World’, ‘Hunky Dory’, ‘Ziggy Stardust’ and ‘Aladdin Sane'.

He is also the author of 'Spider from Mars: My Life with David Bowie', published in 2016. He has played, additionally, with U-Boat and Art Garfunkel. He also, with producer/bassist Tony Visconti, leads Holy Holy, an all-star group established in 2014, which features Bowie material from the 1970s. Holy Holy will be playing 'The Man Who Sold The World' in its entirety and more during their upcoming UK winter tour.

This is Woody’s first interview with Pennyblackmusic. Welcome!

PB: You and Tony Visconti had been major players in David Bowie’s career, but your vision for Holy Holy meant expanding the circle. How did the all-star phenomenon come into play?

WW: Really, it was in 2014. I got a call from a guy who was running the Institute of Contemporary Art in London which is, quite, kind of posh. He said, We’re doing a Bowie week with films and albums and there will be about 300 people at the event every night. Would you come up and do an interview in front of the audience?

I had never done anything like that so I was a bit back-offish (Laughs). I didn’t know if I could do it, or whether I’d sound like an idiot, but he talked me into it and in the end I thought I’d give it a try. It was a really good night and I found that I could talk as well as I could drum, which was quite a revelation.

The Institute had put a band together which was Clem Burke, from Blondie, on drums, Paul Cuddeford, who was Bob Geldof’s guitarist, a guitarist from Generation X and one from Spandau Ballet. They were doing the Latitude Festival here in England, basically playing all the material that I had drummed on.

I had never met them before but we really got on and they said, why don’t you do two songs at the festival, and I thought that would be fun. I’d not played that material for a long time. I played ‘Five Years’ and ‘Ziggy’ and the response was phenomenal. It was really interesting to see sixteen and seventeen-year-olds singing the songs that we’d done so many years ago. We didn’t really encourage sing-a-longs when we did it; we thought if it happened, great, but we weren’t going to encourage it.

So that was interesting, but the other bit that I didn’t realise was that I never thought I’d be sat at the foot of the stage watching Clem Burke play all my drum parts and I kept going, ‘No, no, not that one, no! --I just wanted to walk on and throw him off. He’s a nice lad but…' (Laughs).

Then Blondie were touring again and Clem couldn’t do it because he’d had so many requests to do other gigs, so they asked me, ‘Would you come to be the drummer in your own band?’ Really? (Laughs) So I said alright, if I don’t have to audition, I’ll come. So we did a few gigs and I said, this feels like a tribute, I don’t want to be a tribute thing.

I don’t remember that we’d ever played ‘The Man Who Sold the World,’ the first album that Mick Ronson and I had played on, Tony Visconti played the bass and was the producer. Because of contractual things and management things, we’d never gotten to do it. That’s why I wanted to do the album because I wanted to see what the audience would do with it. And I thought, I can’t really do it without Tony Visconti. I’ll give him a ring. I know he’s a busy man and I honestly thought it would take me a couple of hours, at least, to twist his arm on the phone, and the minute I told him, he said, ‘Woody, wherever you play it, I’ll be there’ and I thought that would take a long time, but no, he said, ‘I’ve done twelve albums with David and every time we do an album, we always talk about ‘The Man Who Sold the World’ and we both regret never playing live the complete album. It’s been on my bucket list.’

He said, ‘Have you got a lead vocalist?’ I said, I’m not sure, as we’ve just started. He said, ‘Get Glenn Gregory from Heaven 17. He’ll kill it.’ I said, ‘Great, let’s get him in.’

We went into rehearsal in London. The first day, we ran through the first number and finished it. Everyone just cracked out laughing, not because it was funny, but because Glenn sounded so powerful.

So we’ve done two American tours. On the East Coast, 29 days, Japan and about four tours in the UK and Europe.

It’s been really good and mainly word-of-mouth, I think. People are not sure what to expect when they come to see us but we’re good. We’re good. (Laughs)

PB: Bowie once said, “I think my career might have taken a different turn if we’d done that,” after listening to ‘The Man Who Sold the World, Live in London’ which Tony Visconti played for him.

WW: David said, ‘Ooh, that’s what we would have sounded like, Tony, if we would have gone out live.” And he said exactly what you’ve just said. That was a nice compliment and Tony said he was grinning from ear to ear when he heard the album. That was nice.

PB: The material on ‘The Man Who Sold the World’ is very diverse and at times quite instrumentally complex. I was especially intrigued by some of the drumming decisions you made back then on ‘Supermen’ or ‘The Width of a Circle.’ Later on, too, on Hunky Dory, your role in 'Quicksand’. These songs are all so different and I imagine you were really challenged not only as a drummer, but as an arranger.

WW: ‘The Man Who Sold the World’ was easy and hard. Mick Ronson and I had been playing progressive rock stuff, from blues to rock for a few years together, from Hendrix to Zeppelin, Cream, all that kind of thing.

At that time, David had just got married. So we set up live in the studio in London. A lot of times, David would just say, ‘These are the verse chords. This is the middle bit, I think. I think this is an end bit and this might be a chorus.’ Oh, my God.

Tony and I were both good at picking things out. ‘That sounds like a verse,’ because we didn’t have a melody or anything to go on, just some chord sequences, so it was best to just play and jam in the studio until we had something that really sounded like a song.

I think ‘Supermen’ was originally called ‘The Cyclops’. So we said, okay, it’s definitely a big monster beat. So it was approaching it like that. We really played what we felt like playing more than anything. Then Tony would go and get David out of the entrance of the studio and say, ‘You need to finish the lyrics and melody for this one’. Twenty minutes later David would come in and we’d play together as a band and he would say, ‘Yeah, that sounds good.’ (Laughs).

‘Hunky Dory’, the next one, now that was very different because David had been to America and had immersed himself within the American cultural, underground movement that was happening, The Warhol scene, Iggy Pop and Lou Reed, and we were also listening to Neil Young and John Lennon and things like that. We were still really good musicians during that whole period and we kind of got to this, ‘Okay, you don’t have to do a drum roll at 300 miles an hour. Sometimes less is more.’

And David when he came back was writing every day and doing good songs. He really found his, ‘I can write and I know what I want to write and how I want to write it,’ which had really not happened before, not 100 percent of it.

Everyone was good, but as a drummer you’ve got to find a beat that rocks. You’ve got to find a beat, or at least get on the same wavelength as the rest of the songs and give it some life and groove and don’t do drum rolls that cost a lead vocalist, and that was the challenge really. (Laughs). It was like, push the song. The song was the thing. We’d really learned that 100 percent by ‘Hunky Dory’ and it paid off. It sounded good. David was writing about similar things than he’d been writing about before but somehow it was more immediate and more understandable and we didn’t have to dig in and wonder what the hell he was talking about. Although sometimes we still did have to dig in to see what he was talking about. Sometimes we’d say, ‘What’s this song about, David?’ and he’d just go, ‘I haven’t got a clue.’ (Laughs) and I’d say, ‘That’s good because I don’t know…’

PB: You cite the song, ‘Five Years’ as especially challenging.

WW: It was. We played it once or twice before recording, which was quite nerve-wracking anyway, to figure out what you were going to play and what the actual arrangement was. We had heard it and knew it was a song about the end of the world but we didn’t quite know what to play and then we got in the studio and David said, ‘I want drums to start this one.’

Thanks a lot. (Laughs). I haven’t even figured out what I’m playing on this one yet. My immediate thought as a drummer was, Could I get in all of my favorite drum rolls and a few cymbal splashes and show off a bit and then start the song? Then I went, if it’s the end of the world, you’re not going to be particularly excited. I thought, I’ve got to get into the mood. I’ve got to get into the emotional place, what you would feel like if it were the end of the world. I did that. I just played it and David said, ‘That’s great. Do that. Do that.’ It just happened and it was perfect when the guitars came in. So that’s how that came about.

PB: When David announced onstage that he would no longer portray Ziggy Stardust at the Hammersmith Odeon in 1973, were you surprised or had you seen that coming due to his past behaviour? Fellow musicians sometimes referred to David as a “chameleon.”

WW: All those kinds of thoughts went into that night. We’d gotten used to him doing things just on the spur of the moment. We’d gotten used to that; it was no longer a surprise or a shock, usually. On the last American tour, and the English tour, as well, he was finding it hard to do an hour-and-a half makeup and then get into the Ziggy thing and do the show and get back to being David Bowie or even David Jones.

You got in the limousine with Ziggy Stardust and it had not been like that before. You didn’t really know how to talk to Ziggy (Laughs). It was very alien. You couldn’t say, my favorite football team is on tonight. He would just get that Ziggy look and you would shut your mouth. So we didn’t know.

My immediate thought was, it’s a publicity stunt. He just decided to do that on the spur of the moment. My second thought was, maybe he’d had enough of touring because it was hard on him and maybe he figures, I’ll just be a writer. It was always a possibility.

The third thing was, maybe he’s just finishing the Ziggy thing. Or, all of the above. But we didn’t know which one it was and it wasn’t until a few days later that, okay, it’s the Ziggy thing that’s finished. And that meant he couldn’t really take the Spiders, as a band, into anything else, because with the Spiders, he would always have to be Ziggy, you know. That was my personal take on it, anyway.

PB: In 2016, Holy Holy was set to play in Toronto when the band got word that David Bowie had died. You made a choice to perform despite the sad news. Now it’s one thing to be a fan in the audience, it’s another to have been so closely aligned professionally and socially with David Bowie, to have shared that history and then to perform live under those circumstances. Now I realise that Tony had this to say: “There’s no better way to work through grief than through music…” But what was it like for you to carry on despite your own grief? How did you do that?

WW: It was really, really hard. We’d been to the Highline in New York on his birthday and we hadn’t realised it was until we got there and then some of the security guards said, ‘We think David’s coming down to sing with you.’ We said it would be great if he does but we hadn’t heard anything about that. But that kind of prompted us a bit; it was his birthday. Halfway through that concert Tony said, ‘Let’s give David a ring.’ We kind of got together and called him and played a really bad version of ‘Happy Birthday’ and we got the audience to sing and held the phone up. And he said, ‘That was really nice. Tell them thank you.’

And he also said, ‘Black Star came out today.’ And they went wild. He said, ‘I’m really glad you phoned me. Good luck with the tour. I’ll catch you later.’

So for us, playing all of his music, the audience, it was a real high point of the tour and then we got to Toronto and about five in the morning, my phone had been going nuts and I thought, we must have gone down well because the phone’s going mental. And then my son got through to me from England and he said, I just heard on the news that David Bowie passed away.

I go, no, it’s five in the morning. Am I dreaming? I pinched myself. It’s surreal. It’s surreal. Anyway, it turned out it was true. We woke everybody up and went down and had coffee and asked, ‘What are we going to do? Out of respect, do we just pull the tour?’

Tony said, ‘Look. This is my input. I worked with David right to the end. Even though I didn’t know he was that ill, he would come in and he would work and then he would have a few hours’ sleep and he’d come back and work again and he kept that up. Then it turns out that he was seriously ill.'

And I said, on the Ziggy tours, sometimes he wasn’t eating properly and he wasn’t particularly healthy. He would get flu really easily. Sometimes you’d hear him talking and say, ‘Are you sure you can sing tonight? Shall we pull the show? Shall we stop it?’

He’d say, ‘No matter what, if you can get on that stage, you get on and you do it. The show must go on.’ Okay, that’s what we should do. And we’d got so many thousands of hits on his website saying, ‘We need you to play more than ever now.’ We thought, it’s something we have to do.

We put the meet and greets in and we met about four hundred of the audience every night. It was amazing. It was different. The first few rows were Kleenex tissues all over, whooping and crying. And I got mad, ‘It’s a celebration. He’d want you to have a good night, so let’s F-ing do that.’ And it was good. We actually did that every night of the tour and met so many people that he’d helped through that period. They had not only lost an artist, whom they’d admired because of the music, it was like a family member had died and we wouldn’t have known that without doing the meet and greets. Some of them had waited years to say, ‘Thank you for the music and thanks for playing.’

It meant so much. It was quite emotional, the whole thing, you know. But it was worth doing for the audience.

It was hard for us because you just couldn’t get it out of your head while you were playing, the idea of playing his songs, how he sang it, and it was like, Ooof, you’ve gone through another one, it’s got to be easier after so many gigs but it was quite tough.

PB: Let’s switch topic to your memoir with Joe McIver, which is certainly a labour of love and a life story, well-documented. Had you kept a journal during the David Bowie years? How did you retrieve such vivid recollections after so much time had elapsed?

WW: I’ve got a very good memory. I remember most of my life (Laughs). Sometimes that’s good, sometimes that’s not. But yeah, I’ve got a good memory and if there’s a grey area I just need people to say, ‘What’s this?’ and that triggers it off.

It’s probably from learning drum tracks. When you learn drums, I’ve got my own mental library of all the good beats I’ve ever heard and drum rolls so when I’ve got a new song to record I go into my own library or I take bits of that song and fit it into this song.

PB: You had to make some choices as to what to include. You had some zany experiences, some that were bittersweet. We saw a spectrum of emotions in this book.

WW: I have to watch what I say here (Laughs). I’d never written a book. I’d been asked about six times at least to do it and I thought, I’m pretty sure David is going to cover this period extensively so I’m not really going to do a book and go into competition with him. Then I found out from him he was never going to do that, so that kind of opened the door a bit. And about three years ago, there seemed to be so many books on the market, The Definitive Bowie, the “this” Bowie. I’d read snippets and go, that’s not true, that’s not true. That’s a lie. That’s made-up. You weren’t even there so you couldn’t know. There were only three of us in that room, things like that, and it would even get to the point where they were going to ask the postman to do one. Do you know what I mean?

I thought, this is ridiculous. It’s just made-up rubbish. People will swallow anything a lot of the time but they don’t know, you know. So I thought, I’ve got to do this for all of us. I just put it there. I just wanted a basic thing, this is how it was. This is how we operated. As friends, this is how we were. As musicians, this is how we operated. This is what we saw and what we wanted to do and I really ended up doing, I’d say, 99.7 percent of of the book myself.

I was looking at it like, if I were a fan, what would I want to know? What questions have I been asked, personally, over the years? And give an insight into it, which nobody else could do, my experience as a spider on the wall (Laughs).

PB: Charlie Watts, John Bonham, Ginger Baker and Keith Moon are drummers that have inspired you. What did you pull from these guys and how did you then develop your own style?

WW: When I first got into drums, I got into blues and early Stones stuff. It was very much copying the beat on ‘Satisfaction’. Then you go to Jimi Hendrix, Mitch Mitchell was like a jazz drummer who was playing things I had never heard before. I wondered what the heck he was playing. I had a record player at the time and I found if I put my finger on the vinyl, and very slightly touched it, it just made the drums come out a little bit louder so I could figure out which tom tom and where the bass drum would go and what is he playing?

So then I did that with Cream and Bonham. My girlfriend at the time lived above a dance studio. The lady who ran it really liked me. She said you can set your drums up and use our big speakers to put albums on and play along if you want. So I’d set my kit up and put Hendrix on and learn all those fills and apart from the actual drumming, you learn what a good beat was, at least from your viewpoint, where the beats really meant something and then I put them in my library of, that’s a good beat, that’s a good groove. So then when you heard something, like a new song, you had all this information that you knew you could play.

And it was also a good confidence-booster, learning that way, because you thought, I can play everything that Bonham’s playing. I can play everything that Mitch Mitchell’s playing and Charlie Watts. Keith Moon was a bit weird but I liked his attitude. He was probably the most entertaining drummer I’ve ever seen. He gave me that side of it. I guess, the solidness of the playing of these guys. They found a way to bring a song to life. They gave it life and meaning. That’s what it was all about for me, learning from those guys.

I always got the John Bonham kind of thoughts: ‘If it doesn’t mean anything, don’t play it.’ Don’t play a little light fluffy bit just to be playing. Wait until you can really play a new thing and then play. I always adapted that approach which helped me on things like ‘Ziggy’ and ‘Hunky Dory,’ even. You’re learning from guys that you admire what they’re doing.

But I learned these things and I didn’t know any drum basics. I didn’t know drum rudiments at that time. I’d learned them all by ear and then I was doing a gig with Mick Ronson at the Cavern in Liverpool, the famous club, and there was a band on called Tear Gas that were kind of underground in this country but they’re really great musicians.

I was at the bar and this drummer played a drum fill and I just turned around, like The Exorcist. What the hell was that? I had to go find him afterwards. I said, ‘On that fourth song you did, you played that drum roll’ and then he spoke to me in drum speak and I thought he was a foreigner.

I said, ‘Are you foreign?’ And he said, ‘No, I’m from Scotland but I’m just giving you what the patterns are. Don’t you know drum rudiments? They’re the basic stick patterns.’ I said that I’d never heard of them. And so he took me round the back and showed me a few (Laughs.)

I said, ‘God, that’s it. I’ve got to learn these’ and then I found that a lot of things I’d learned, they were rudiments, but I didn’t know that. I didn’t know what I’d learned. But it was really good because then I could improve on that, knowing what I was improving on. It’s always, you get new songs from anybody, like when I’m doing session work.

All music is down to duplication Can you understand and duplicate what this guy is trying to actually say? It might not be in the lyrics, you’ve just got to find, what is he trying to get across to another person? And if you can get that, then you know what you’re contributing to, you know what you’re adding to. Then you use your skills to work out beats and patterns that actually state that message, not some other message that doesn’t say the same thing. Does that make sense?

And it’s not difficult if you approach it like that. It’s really just asking, ‘What is this artist trying to say?’ And then after that, make it say more.

PB: I’m sure you’re excited about the upcoming UK tour.

WW: It’s the first time we’re doing both ‘The Man Who Sold the World’ album and ‘Ziggy’ in the same set, basically. So it’s going to be a challenge, but it’s going to be good. We’ll sneak in a few of the favorites that we’ve got. It will be a good night.

PB: Will you let us in on the favourites or is it a surprise?

WW: No, it’s a surprise (Laughs). But we’re looking forward to the tour and we’re probably the only band that plays in the true spirit of the songs. There are probably ten thousand musicians out there that can play those songs if they can work out the chords but the thing we did with David was, we didn’t care about the wrong notes. It’s the spirit of the song that you’ve got to get across to the audience so we’ve always worked with that as our stable target as such. Not that we play a lot of bum notes, but the spirit of it is the senior thing, as long as it’s not stupid. Do you know what I mean? Does he mean it? So, yeah, we mean it, man.

PB: Thank you.

Band Links:-

http://www.woodywoodmansey.com/

https://www.facebook.com/woodywoodmans

https://twitter.com/woodywoodmansey

http://www.holyholy.co.uk/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mick_Woo

Picture Gallery:-