Slits

-

Interview

published: 13 /

10 /

2018

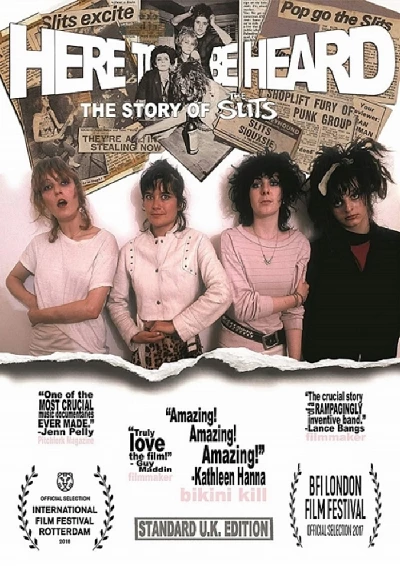

John Clarkson talks to Tessa Pollitt, the former bassist with seminal all-girl punk band The Slits, about the new film documentary 'Here to Be Heard: The Story of The Slits’, and its accompanying scrapbook.

Article

“I do feel that we had an effect in what we did,” says Tessa Pollitt towards the end of our interview. “And that gives me a certain amount of satisfaction. I am going to be 60 next year, and I still feel the same way and have the same passions as I did as a teenager. It is important to be yourself, and even if you don’t fit in, that is okay. Who wants to fit into the rules of society?”

Pollitt was the bass player with the first all-girl punk group, The Slits. She is talking to Pennyblackmusic to promote ‘Here to Be Heard: The Story of The Slits’, a new documentary film about her former band.

‘Here to Be Heard’ received its world premiere at the BFI London Film Festival in October last year, and Pollitt, the group’s Spanish-born original drummer Palmolive, and the film’s director William E Badgely, have gone on to participate in a run of regional tour screenings and Q and As across the UK. While ‘Here to Be Heard’ has already been released on DVD, it is about to be reissued again, this time packaged with a reproduction of Tessa Pollitt’s scrapbook on The Slits.

The scrapbook, which has a central role in the film, was started shortly after Pollitt joined The Slits as a 17-year-old in 1976. Every time The Slits appeared in a newspaper or one of the weekly music ‘inkies’, she would cut out the article and paste it into her scrapbook.

Both the scrapbook and Badgely’s film provide a unique perspective into the history of the influential but controversial Slits, who attracted the wrath of both the right wing press and (perhaps more surprisingly) hardcore feminists alike, with their manifesto of personal freedom and female unity.

The Slits were formed in London by their then 14-year-old singer Ari Up, the daughter of German publishing heiress (and the future wife of John Lydon) Nora Forster, against the backdrop of the short-lived yet legendary Covent Garden punk club The Roxy. They settled quickly on a line-up that also consisted of Pollitt, Palmolive and guitarist Viv Albertine. The group quickly attracted attention for its wild stage act, and was selected by The Clash after just its second gig to join them as their support act on their infamous ‘White Riot’ tour.

The Slits initially thrived on aggressive amateurism. The last of the first wave of punk acts to sign a record deal, the photo on the sleeve of their 1979 debut album ‘Cut’ drew them further controversy, showing Ari, Pollitt and Albertine naked from the waist up and caked like Amazons in mud as they defiantly eyeballed the camera. Musically, however, it revealed an increasingly sophisticated act which merged punk sounds and dub beats with African tribal rhythms. It was produced by reggae musician Dennis Bovell in Jamaica, which helped cement the non-punk elements of their sound.

For their second album, 1981's ‘The Return of the Giant Slits’, The Slits switched labels from Island Records to CBS. It built on the sound of the first album with added jazz textures, but it sold poorly and the group broke up within weeks of its release.

Ari Up spent years living in the jungles of Borneo and then latterly Jamaica before returning to Britain to reform The Slits in 2005 with Tessa Pollitt in a new line-up that included future Mercury Award nominee and solo artist Hollie Cook. The group toured widely and released a third album, ‘Trapped Animal’, on the Los Angeles-based label Narnack Records in 2009, but came to an end when Ari Up, who for a long time had refused chemotherapy as it ran contrary to her Rastafarian beliefs, lost a battle with cancer at the age of 48 in October 2010.

Tessa Pollitt admits to Pennyblackmusic that she “hates” being interviewed “although is getting a lot better”, but proves to be articulate and humorous in conversation.

PB: Did you find in the Slits’ early years that men and women reacted in a different way to you?

TP: I think straight down the line people are just people. It has been interesting at the Q and As that I have done recently for ‘Here to Be Heard’ in cinemas that the audiences have been male, female, of all ages.

When we first started, some men would just stand there at gigs with their mouths open, thinking that the aliens had just landed (Laughs). You could see it in their faces. What the hell are these women? Are these women? What we were doing was groundbreaking. It was only, at that stage, partially conscious as we were all very young, but we weren’t happy with what we saw mapped out for us for the future as females. We did, however, have great support from our male peers. Groups such as the Clash and the Sex Pistols got us, and recognised that we weren’t playing the game.

I don’t really know if there was that much of a divide between men and women in their reaction to us. A lot of women didn’t like us either. We even annoyed the feminist movement with our record cover for ‘Cut’, but they didn’t get the humour or the fact that we saw ourselves as female warriors.

PB: How did other punk women such as Poly Styrene and Siouxsie Sioux react towards you?

TP: We never really hung out with each other, so I don’t really know. I got to know Poly Styrene, much later in life, maybe about two years before she died, and we became very close indeed. She had a funny story about when she was playing The Roxy with X-Ray Spex how Ari as a fourteen-year old pulled the lead out of her microphone. I wasn’t aware of that until she told me years later.

We were all different. Each group had a different message really and there was definitely an element of competition between us, so we didn’t really hang out in the day. I don’t really know what Siouxsie or Poly thought of us even now.

PB: Viv Albertine says in ‘Here to Be Heard’ that there were no female role models in music and she never thought of joining a band until she saw John Lydon at a Sex Pistols gig. Did you feel the same?

TP: I did feel the same. At the time that there weren’t any female role models, but now in hindsight I have discovered several others, such as Jacqueline du Pre from the classical world, who was an amazing cello player, or Sister Rosetta Tharpe who goes way back to the 1930s and played the electric guitar.

Nico from the Velvet Underground also was an inspiration to me at time. I think Viv was referring more to the typical folk female guitarist that wasn’t really pushing any boundaries and that was pleasing to the eye, pleasing to the ear and little else.

PB: You apparently had never played the bass until two weeks before the Slits’ first gig. Is that true?

TP: I had messed around on guitar as a 14, 15-year-old with the David Bowie songbook, but I was just messing around. When they asked me to join the Slits and to play the bass for them I said as a 17-year-old, “Yeah, I will give it a go,” so I learnt it like a parrot in two weeks (Laughs).

PB: ‘The News of the World’ somewhat over-reacted by saying about the Slits just after you formed that they “made the Sex Pistols look like choir boys”. Was that something which bothered you?

TP: No, I just thought that it was funny. It was the media putting a label on us, and I guess that we were a bit more shocking than the Sex Pistols because we were girls and girls weren’t supposed to behave and present themselves like we did. For me, however, as it was for the other Slits, it was quite naive and unconscious and I was just following my instincts..

PB: The Slits supported the Clash on their ‘White Riot’ tour after having just played two gigs together. You have described it as like “St Trinian’s meets the Bash Street Kids”. What did you mean by that?

TP: It was like we were all on holiday together in a tent. We were all travelling together in the coach, and everyone was being silly. It just reminded me of being school, even though I never went to school with boys. It was an all girls’ school. But there was a serious element as well. It was a groundbreaking tour, and a real opportunity for us to be playing on these huge stages in front of a lot of people. We weren’t used to that.

PB: There are remarkable stories about that tour, such as the Slits turning up at hotels and not even getting as far as the room once the managers there found out your name. Did that come as a surprise?

TP: We became accustomed to it (Laughs). I had ‘The Slits’ graffitied on my guitar case. I don’t find the name ‘The Slits’ that shocking myself, but it prevented us from being playing on the radio. It wasn’t the music. It was the name. In the same ‘News of the World’ article they said that they couldn’t print our name in a family newspaper because it was too offensive, and yet n that same piece they also put the Sex Pistols right at the top. It was a total contradiction, and absolutely stupid.

The person who most supported us throughout was John Peel. I don’t know what we would have done without him, as we then did get radio play and recordings before we got a record contract.

PB: You signed to Island and reggae artist Dennis Bovell produced ‘Cut’. What do you think he brought most to the recording?

TP: Dennis recognised our passion and love of reggae. We grew up with reggae. There were no punk records initially but Don Letts used to play reggae at The Roxy., so Dennis appreciated our love of reggae. He also had a very similar sense of humour. He really disciplined us, which was what we needed musically, and he was the perfect person at the time for us to work with. He really did a fantastic job, and we worked extremely well together.

PB: ‘The Return of the Giant Slits’ did less well. Were you surprised when it sold badly?

TP: It was a disappointment. I think that people expected us to do the same thing again. We were, however, constantly evolving and changing, and it is not like we had hit a formula with ‘Cut’. We wanted to experiment and try things new out. We were, however, equally criticised with ‘Cut’ because people thought it wasn’t punk enough, that it was too polished, that it didn’t sound like our early John Peel sessions. There was constant criticism. It became water off a duck’s back. We came to expect it.

PB: It seemed that you broke up abruptly. Was that the case?

TP: From what I remember, Ari had just become pregnant with her twin boys. I think she was itchy to get out of England. She was more suited to a hot climate such as South America where she initially went. I think we had just run our course at that time. I spoke to Ari afterwards and said, “Why didn’t we just take a break? Was it just necessary for us to kill it dead?” because I do think that we could have continued. As we were so young when we started, I think, however, we needed to go off on our separate ventures away from the group, and that is basically what happened.

PB: You and Viv both, however, abandoned music for a long time after that. Viv was gone for about thirty years and you were also away for many years. Was that just because the break-up was so devastating and intense?

TP: It was. It was very traumatic living this exciting life, and, then suddenly you are not interesting to people anymore. I did play a bit of music in a short-lived group which featured Sean Oliver, who was the father of my daughter, and I also messed around a bit with the cello. It was a traumatic change, and I didn’t really have much contact with Ari for years and years.

PB: When you did meet up with Ari again how quickly did you to decide to reform the Slits?

TP: It was Ari’s idea. I think that she asked each individual Slit, Viv and Palmolive and me, and I really didn’t want to do it at first because I hadn’t played the bass for so long. I didn’t know if I was capable of doing it, but she bent my arm backwards and I have no regrets.

I had just under five years with her making music with some new young members including Hollie Cook. It was very different but it was very exciting and we went to Japan, Australia and did big tours of America. For the younger members it was like an apprenticeship. Things with Hollie have taken off amazingly. It was very much about giving a voice to them as well, and I am very proud of the album ‘Trapped Animal’ that we did.

PB: Ari seemed to deal with her cancer by ignoring it as long as possible. At what point did you become aware that she was seriously ill?

TP: It didn’t appear when we reformed the Slits that she had anything wrong with her. I don’t think that she did at that stage, and then she gave me some inclination that there might be a problem and that she had seen a doctor in Jamaica but that she hadn’t really followed the advice that she had been given. Then she told me later that she seemed to be getting better, and this is where the confusion kicks in.

When we did our very last tour of Europe, it became more and more obvious that she was extremely ill. By that time it was definitely too late. The cancer had spread to her liver and then ultimately it spread to her bone. Then very much towards the end she was in hospital in Santa Barbara and they told her that you should really try some chemo because you have got two weeks to live, so she did finally submit to it and I think that gave her an extra two or three months. The whole thing was an absolute tragedy, however, because chemo can cure you if you tackle things early enough. Ari was, however, not the sort of person that would listen or that you could convince. She was very much of the Jamaican belief, like Bob Marley who also refused it and surgery. That chemo was wrong.

You have to allow a person to deal with their death in their own way. When someone dies, you do think that I wish that I had insisted on this but it was never clear how ill Ari was until it was too late. I think that in a way that she was also pushing us away from her because she wanted to deal with it on her own.

PB: Who is William Badgley who directed ‘Here to be Heard’?

TP: Bill had made one music documentary before called ‘Kill All Red Necks Quick’, which got a laugh at the Q and A. He was born in 1976, so he is a lot younger and didn’t really know a great deal about us beforehand.

The film was started off by Jennifer Shagawat who was our tour manager. Ari insisted that she film everything to do with the second Slits and on tour, so we had loads and loads of footage and we didn’t know what to do with it. After Ari died, we agreed because it was her wishes that we had got to do something with it. Then we realised that we had got to tell the whole Slits story and that we couldn’t just tell the tail end. Jennifer put in the initial financing herself and that is when she pulled her friend Bill in because she didn’t really feel that was her field to complete the documentary. So, we included some of her and Ari’s footage, and then we managed to get a lot of archive footage from Don Letts, our manager Christine Robertson and other sources.

PB: You and Palmolive are credited as Executive Producers. What did that involve?

TP: We were involved right from the beginning. We contributed personal photographs and we had some form of say in the documentary itself, although I didn’t really feel that I had 100% say. I had to hand it over to Bill. He didn’t really know the Slits story, so we had to guide him in some form.

PB: Your scrapbook takes a central focus in the film from the start. Whose idea was that?

TP: That was Bill’s idea. Luckily I had saved my scrapbook that I had started in 1976. It was a very useful tool to stimulate me into talking and remembering about things. If we were ever in the paper, I would cut it out and paste it in my scrapbook.

PB: The Slits have been described as changing traditional roles about femininity. How would you like them to be remembered?

TP: Funnily enough, Bill’s mother – who is very straight, American and Republican – was asked, “How would you describe the film?” and she just said in one word, “Freedom.” I loved that because you can get every analytical about it, but I think that the film and the Slits are about freedom.

I can see that it has gone through all the generations because the youngest person in the room in the audience at one of the Q and As was an eight-year-old from Brazil, l and I was like “Wow!” She asked me to sing a song and I said, “Well, I am not really a singer but I will give it a go,” so I sang a bit of ‘New Town’

That is, to me, so heartwarming that it has travelled so far. I don’t really think he music has dated even that much, and the lyrics are still relevant today from certain songs, so it is certainly about freedom.

Women are still struggling, so I think the message needs to continue. I think there is a lot more work that needs to be done, but it is important for women to carry themselves in a certain way and keep fighting.

PB: Thank you.

Band Links:-

http://www.slitsdoc.com/

https://en-gb.facebook.com/slitsdoc/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Slit

Picture Gallery:-