published: 16 /

9 /

2017

Paul Simpson talks to John Clarkson about his forthcoming memoirs 'Incandescent', his post-punk group The Wild Swans and his memories of late 70's/early 80's Liverpool and its bands

Article

It is sometimes those on the margins and edges than those that are thrust into the often empty glare of fame that have the more fascinating lives.

A cult musician’s musician, Paul Simpson has never achieved quite the same notoriety of some of his contemporaries and friends from the fertile Liverpool music scene of the late 70’s and early 80’s, but he has his own remarkable story to tell.

As an eighteen year old at the point in which punk began to mutate into post-punk in early 1978 he was in a band A Shallow Madness with both Julian Cope and Ian McCulloch. He also shared a flat with the late Echo & The Bunnymen drummer and motorcycle enthusiast Pete de Freitas and latterly Courtney Love.

And then there is his band The Wild Swans, for many years one of the great lost groups and in which he is the vocalist and lyricist, that he formed after co-founding The Teardrop Explodes with Cope before leaving it in the spring of 1979 after playing keyboards on their debut single, ‘Sleeping Gas’.

The Wild Swans pointed at huge potential with their own 1982 debut single, the lush and anthemic ‘Revolutionary Spirit’, which was the last release and only 12” single of the pre-KLF Bill Drummond’s Zoo Records, but broke up in swift acrimony within weeks of its release.

After releasing three singles with Care which also featured the Lightning Seeds’ Ian Broudie and having a minor hit with their debut single ‘Flaming Sword’, Simpson reformed The Wild Swans in 1986 with original guitarist Jem Kelly.

They had, however, lost much of their initial magnetism. The group’s long-awaited debut 1988 album, ‘Bringing Home the Ashes’, which was released on American major label Sire Records and which Simpson has since disowned, was a disappointment, and its psychedelic-tinged 1990 follow-up ‘Space Flower’, while better, with Kelly having left again, was a solo album all but in name and sold poorly.

Crushed by the experience, Simpson dropped out to focus on his instrumental electronic project Skyray, before finally reforming The Wild Swans in a new line-up after an absence of nearly twenty years in 2009.

Two vinyl only singles that year, ‘English Electric Lightning’ and ‘Liquid Mercury’, released on indie label Occultation Recordings, finally fulfilled all the initial promise of ‘The Revolutionary Spirit’, and an autobiographical album, ‘The Coldest Winter for A Hundred Years’, when it followed in 2011, which found Simpson reflecting on his past and the Liverpool of both his youth and the 21st century, was a triumph.

A follow-up was promised quickly, but then, with all the further ill-fate that has dominated The Wild Swans throughout their career, Simpson contracted a virus while on holiday in Sri Lanka, damaging his vocal chords.

Paul Simpson is currently crowdfunding his memoirs ‘Incandescent’ through the on-line publishing house Unbound. We are publishing an extract from it beneath this interview.

When we set up this interview, we offered Simpson, who we have interviewed three times before and last in 2011 at the time of release of ‘The Coldest Winter for a Hundred Years’, the choice between doing the interview by e-mail or phone, and he opted for phone.

He is an extraordinary writer, and ‘Incandescent’ promises to be an extraordinary book.

PB: You have been your own worst critic in the past and been particularly harsh about ‘Bringing Home the Ashes’, a record which you told us in 2003 that you “can’t abide.” How do you feel about ‘The Coldest Winter for a Hundred Years’ now and six years on? Does it still stand up?

PS:It’s not perfect, but I believe ‘The Coldest Winter’ album has a musical potency and a lyrical purity that stands up. The expanded version with the 3-spoken word tracks included is a beautiful thing. I’ll never disown it in the way I did with ‘Bringing Home the Ashes’. My problem with our debut is no longer the 80’s production, because weirdly, after 30-years it has acquired a sonic patina; a period-charm that means that incrementally, it sounds better with each passing year. My issue is with the songs. Musically they just don’t reflect a fraction of the potential of that group. They don’t even reflect how good we were at the time of recording it, and lyrically I’m faking it a bit, wearing a mask that doesn’t represent the haunted young man I was at the time. Compared to ‘The Revolutionary Spirit’ and the BBC radio sessions for Peel and Jensen, ‘Bringing Home the Ashes’ just feels underwhelming. Its life-force is absent, like eating an irradiated strawberry.

When we reformed for the Mk.2 phase, just before we signed to Sire Records, our original keyboard player Ged Quinn abruptly left us to pursue his painting career. In losing him we lost his classical music influence on the writing. Without his input and his ability to temper young guitarist - Jeremy Kelly’s impatience at how slowly things were moving, we wandered from the path. We mistook a Will-o’ the-wisp for the flickering lantern home and got lost in the marsh. Instead of replacing Ged, Jeremy and I tried to soldier on alone pursuing a harder and more direct approach with the writing. In doing so we gained the attention of the Americans but we threw out the epic grandeur, our most dazzling weapon. In our defence, this modern sonic streamlining was a very zeitgeist thing to do. Lots of credible indie-bands did the same thing at the same time. It’s the difference between say, Aztec Camera’s ‘High Land, Hard Rain’, ‘Knife’ and ‘Love’ albums. All great records, but to my ears, Roddy’s unique and beautiful mystery was diluted a little with each successive record in pursuit of a wider audience. I don’t think that was ever his intention, it certainly wasn’t ours, it was just the natural pull of the times.

Somewhere in the transition to a major label The Wild Swans forgot to be magnificent. The sad thing is, the magic was still in us. ‘Holy Holy’, a quickly and cheaply recorded B-side of that very time is an amazing song, as is ‘Holy Spear’ from the Janice Long session we recorded just before signing.

‘Bringing Home the Ashes’ is a really good pop record, but it’s not an ‘important’ record. Again, ‘Space Flower’ is a great alternative bubble-gum album, but is not a vital record. It’s the sound of me, reeling from a bandmate’s betrayal and cutting off my nose to completely disfigure my face.

PB: You said at the time of the ‘Electric English Lightning’ single that “in returning from the ambient wilderness I am not trying to recreate the unique sound of the former members…It is the original spirit of the group I am after… different but the same.” Do you think that you achieved that or came close to achieving it with ‘The Coldest Winter for a Hundred Years’?

PS: My intention when entering the studio on the ‘Coldest Winter’ sessions was to try and bring back some of the gravity and beauty of the early Wild Swans radio session tracks. Mission accomplished in my opinion. Particularly on tracks like ‘The Bluebell Wood’. It wasn’t all about looking backward however, I think we broke new Wild Swan ground on that album too. Lyrically, I think I nailed something I’d been trying to say my whole life about this beautiful and fucking terrible country.

PB: In 2013 you contracted a virus while on holiday in Sri Lanka which damaged your lungs, putting your musical career on hold. How is your health now? Could you ever conceive of releasing a fourth Wild Swans studio album now?

PS: I’ve lived with the fallout of this virus for almost four years now, and although it’s not going to kill me, it is a significant presence in my life. The initial fever only lasted 24 hours. It’s like a computer virus that runs invisibly in the background, not deleting files but affecting performance speeds. It’s not quite the spinny-wheel of death, but it has, so far, dodged my thoracic consultant’s Antivirus software and corrupted my hard drive a bit. The first year was the worst. Just climbing a flight of stairs exhausted me and the slight lack of oxygen in my blood resulted in sustained periods of brain-fog. I couldn’t remember people’s names, and at its worst, the names of my friends. Mercifully both the fatigue and brain fog have evaporated now, but my breathing is still affected. My voice has changed, it emanates from my throat now and not my diaphragm. So far, no breathing therapy or vocal exercises have helped. I’ll just have to do a Dylan after the motorcycle crash and reinvent myself. I always hated my voice anyway. To my ears, I sound like a posh clergyman. Ironic, considering I was born to working class parents in a two up - two down terraced house Huyton, Liverpool. My mother sold a rifle to buy us a stair-carpet FFS!

I ’m itching to do a new Wild Swans album. After ‘The Coldest Winter’ album, I feel liberated. I can tear up the original blueprint and voyage onward. Sonically, structurally and lyrically. I’d approach the next record completely differently. I envisage something more improvised, extended; ambitious and free. It’s just a matter of me anchoring a confident vocal. Lyrically, I want to make a definitive statement about the role of the artist and my obsession with remembering one’s purpose in life. We came down to this dense, yet magical plane of existence for a reason; and it wasn’t to post photographs of kittens or our lunch on Facebook and Twitter. We are magnificent spirits temporarily housed inside a damp cave of flesh. We have forgotten our culture, erased every vestige of ritual and magic from our lives; with the result that we have forgotten our purpose and the job we came here to do. If I could afford to, I’d book a studio tomorrow. Until then, I am experimenting.

One of these experiments is a collaboration with ex-Montgolfier Brothers pianist and guitarist, Mark Tranmer. Mark and I met a few years ago at a Momus gig in Manchester. We kept in touch sporadically but only recently started exchanging ideas and demoing. The plan is for us to self-release a vinyl single in the near future. We don’t have a name for the project yet but the two tracks we are working on sound very filmic. One side sung, the other narrated. Mark and I hear the two songs we’ve settled on as the opening and closing credits to a lost film. All we know is it was shot in what looks like Prague in winter by an Italian new-wave director, but the footage is so degraded that the only section that has survived is a long travel montage featuring masked couples having sex in the separate compartments of a moving train, and all of them superimposed over an aerial shot of the locomotive’s progress as it barrels across a burning map of Eastern Europe.

PB: When we last spoke you had seven or eight unreleased leftover tracks for ‘The Coldest Winter for a Hundred Years’ and were working on demos for a proposed next record. The Wild Swans have made an art of unearthing and releasing lost songs in the past with both the ‘Incandescent’ and ‘Magnitude’ compilations. Can you see those tracks ever coming out now?

PS: I’m not sure how artistically valuable the demos and songs left over from ‘Coldest Winter’ sessions are to be honest. Because I am so focused on finishing the memoir, I’ve not had the headspace to listen objectively. The best one for me is called ‘Punk Jerusalem’ - the home demo of ‘English Electric Lightning’.

PB: You lived in poverty in the in the flat you shared with Pete de Freitas. You have said in the past that you were “starving, frozen, lovelorn and hallucinating in my bedsit”, but also that “in the late 70’s and early 80’s Liverpool was my Paris, a city in the grasp of recession but pregnant with magic.” How long did that golden period last for you? Why was it so magical?

PS: Well, you don’t recognise it as poverty when you are living it. You are too busy keeping warm and just surviving. I’d say my ‘Paris’ years were mid-1976 to the December of 1982. What I miss, and probably over-romanticise about those days was the crackle in the air. The sense that we, the post-punk bands were directly influencing culture. It felt like new territory was being gained with each great new indie record release. Punk had kicked opened the over-ornamented doors of prog-rock, but within 12 months of ‘New Rose’ and ‘Spiral Scratch’ and ‘Anarchy’ coming out, it was over for me, its job was done. I didn’t even buy ‘Never Mind The Bollocks’. The first two Pistols’ singles scorched the ground so effectively we didn’t need more of the same. Musically and lyrically, what came next was far more interesting.

This isn’t exactly on topic, but it is my belief that the government have termed this current period of ‘austerity’, this loveless vacuum, this absence of humanity; a ‘recession’ in order to psychologically limit its severity in our minds. Recession implies its temporary. This is not a recession, it’s a full blown depression. At least the austere period we survived in the early 80’ spawned some astonishingly potent music. I’m hoping this one does too. Since the EU referendum, there’s been a palpable crackle in the air.

PB: Your first band before you co-founded the Teardrop Explodes and then the Wild Swans was A Shallow Madness, which also featured Julian Cope and Ian McCulloch. Was it ever a proper group with you having assigned roles? It was apparently very short lived, lasting only a couple of months. Did you record any material?

PS: A Shallow Madness was a bone-fide group in that we had a full line-up and regular rehearsals. To all intents and purposes it was The Teardrop Explodes but with a different drummer and Ian McCulloch singing. If he had only turned up on time, even once, we might have made a single. Even when Mac did he deign to make an appearance, he just wasn’t trying, he hadn’t written lyrics or done any work on melodies. Week upon week, no progress was being made and frustrated, Julian mooted the idea that we should let Ian go.

Guitarist Mick Finkler, drummer Dave Pickett and myself all concurred, but hadn’t imagined Julian in the role of frontman at all, which, granted, must seem peculiar to his fans, but Ju just didn’t look, or present like a frontman at all. Singers, in my opinion have to be haunted by something, or addicted to something, or, at the very least, be hungry of soul. Back then, Julian was none of those things. His demons arrived post Teardrops. In my opinion, he made one of his most brilliant records, ‘Fried’, when he was lost, between marriages, between Liverpool and Tamworth, between heaven and Hell.

PB: Various reasons have been cited for The Wild Swans ‘original break-up including no manager, a lack of leadership in the group, your youth and being thrust into the spotlight too quickly. You have also fought a lifelong battle with depression. How much was that also a factor?

PS: The truth of why the band split is in the book. The bottom line is I was betrayed, and then betrayed again. In their defence, my bandmates knew nothing of my depression, because I was never depressed in their company. I loved them, the band were both my antidepressant and my painkiller. That’s why I never got over the hurt.

PS: One of the more unlikely but true stories in the book is that Courtney Love was your flatmate. How long was she your flatmate for? What do you remember about her?

PS: Courtney and her best friend Robin Barbur lived in the flat I shared with Bunnymen drummer Pete de Freitas for less than a year. Pete and I were sub-letting the place from Julian and his first wife (Kathy Cope) who had recently separated. Julian was gigging and recording down in London and Courtney was dogging his footsteps (at least this is the story Julian told me years later). To get rid of her, he suggested she come up to Liverpool and hang in his flat with us for a bit. We couldn’t get hold of Julian by telephone to verify her story. We really didn’t know the status of his relationship to these two young girls so we felt obliged to let them have a room.

Courtney and Robin were just a little loud for us reserved, trout-eating Brits. We didn’t relish sharing our home with two hi-res, ultra-vivid strangers. In their defence I think they thought it Julian owned the place and as a consequence made little or no attempt to find accommodation of their own. I feel so sorry for the young Courtney in Liverpool now. She was clearly lost and looking for someone to love her. With an upbringing as difficult as hers, how could she have come out any other way? In retrospect, Pete and I could have been a little more understanding of their situation, but then, she and Robin could have shown a bit of respect for our home and personal belongings.

PB: You have been working on your memoirs for many years. How long have you spent writing them and which years do they cover? Is it your entire life story?

PS: Well, I started writing them twenty years ago but shortly after I became a father, which necessitated abandoning work on them for several years. My memoir covers my whole life but it’s not indulgent. Every sentence is vital to understanding my mission. My stomach sinks when I open a memoir and it begins ‘My Grandfather was born in’ Yadda Yadda. I’m sorry, but unless your grandfather was Sigmund Freud, Salvador Dali or actually born in a town called Yadda Yadda, I honestly don’t care.

The music stories in ‘Incandescent’ are a Trojan Horse as far as I am concerned, there to attract attention while I sneak in what I believe is the most original thinking in the book; what happens in between the bands and in between the record deals. What happens when the money run out and one’s sanity begins to dribble out of one’s ears? When the Sire deal expired after ‘Space Flower’ was released, I became mentally very abstract. I spent six months nailing tree bark to wall of my cellar. ‘Incandescent’ is entirely written in the present tense, so the reader is privy to my internal, infernal monologue.

PB: You recorded three remarkable autobiographical spoken word pieces – the title track, ‘The Wickedest Man in the World’ And ‘Half Life’ –as B sides for the ‘English Electric Lightning’ and ‘Liquid Mercury’ singles and for ‘The Coldest Winter for a Hundred Years’ sessions. Do they appear in the memoirs?

PS: I’m flattered you think they are remarkable. I’m very proud of them. All three were just sketches I brought in and improvised with the band on the day in the studio.

The text of ‘The Coldest Winter’ track was lifted straight from the memoir. I just edited it a little to fit the time constraints of the B-side it was originally intended for.

‘Half-Life’ is another edit from a chronologically more recent book chapter called ‘Death in a Pencil Skirt’. It concerns a very specific period just after I returned from the jungles of Sri Lanka, after the initial fever, when I first symptoms of illness appeared. In an attempt at getting a diagnosis, I attended the School of Tropical Medicine here in Liverpool, taking fluid samples three times a week to try and identify the parasite I’d somehow ingested in the right stage of its life cycle. It was winter and bitterly cold. Convinced I was going to die of this debilitating thing, I’d walk to hospital like some Mersey Raskolnikov, wrapped up two coats and three scarves and fingerless gloves. While I walked I’d listen to the adagietto from Mahler’s ‘Symphony Number 5’ - the theme to Visconti’s 1971 film of ‘Death in Venice’ on an I-pod. I was given radioactive injections in order to get ultra-high-res x-rays of my lungs. As the injection went in, on monitors, I watched my lungs fill with what looked like with sparkling black glitter. In ‘Half-Life’ this terrifying image morphed into Montgolfier’s air balloons on fire over 18th century Paris.

PB: When we last spoke to you in 2011 you had a literary agent and were looking for a regular publisher, yet you have decided to release it through Unbound and a crowdfunding campaign. Why have you decided to do that?

PS: An agent requested the book’s introduction and three sample chapters, and after reading it and agreeing to represent me, he suggested that in order for him to get me a better deal, I finish the whole book. Well, because I knew I needed about 100,000 words to tell my story, I simply didn’t have the time or, being a new father, the internal peace to complete it. So it lay for years in Word files on floppy discs, CDRs, USB sticks and hard-drives until, Unbound contacted me a few months ago, read a few extracts and offered me a contract. I thought, “Paul, if you don’t do this now, you never will.” Funding it is a bit of a bugger however. I don’t enjoy selling myself on social media at all. At best I feel like a social-media nuisance, and at worst, a rock prostitute.

PB: You were spending some time working on a horror film script when we last spoke. Has that been completed? You also had another career beyond music writing radio plays. Do you have anything planned there?

PS: It was a psychological horror called ‘Ornithology’, a collaboration with my best friend, the playwright Jeff Young. I’d come up with the premise and the two of us fleshed it out in the pub on index cards over a period of about six weeks. We then spent an insane week in Bill Drummond’s Curfew Tower in Cushendall in County Antrim shaping it into a first draft, but shortly after, Jeff became busy working on several BBC radio commissions and writing his own play. Our film script was genuinely terrifying. Not drawn from any existent horror trope. It was I believe, a wholly original idea. I hope we get to finish it someday but I fear it may have missed its time. A shame as that story was brilliant.

My play, ‘Permafrost’, is based on a short story I wrote about a man who believes that snow is falling from the ceiling of his first floor bed-sitting room. His bed rests upon the surface of a frozen lake. By Act Three he’s in a birch forest in a Siberian Gulag. It’s really about how, if placed under enough stress, this thing we, by consent call reality starts to dissolve. By chance, my story was read by the Literary Officer of the Everyman Theatre here in Liverpool. At her insistence, I pitched it to the theatre’s Artistic Director who liked it enough to commission me to develop it into a play. At the same time my marriage was beginning to disintegrate, which wasn’t ideal conditions for creativity, then the Everyman reverted back to a repertory company model with fourteen full-time actors on the pay-roll; so all of a sudden, my play for one actor wasn’t quite so viable. So, for the time being we’ve consensually agreed to press Pause.

Funny thing is, I may have temporarily lost my commission, but the silver-lining is, two years later, Gemma, the Artistic Director who I pitched it to, is now my partner. Life is surreal. The thing is, she gave me a really, really hard time at that pitch.

As well as writing fiction, I paint in oils; and always the same thing. I call them my N.D. E’s. My Near Death Experiments. The visual equivalent of ambient music. Large, eventless foggy seascapes. It’s a long story but just before going to Sri Lanka, I nearly met the grim reaper on a Scottish Sea Loch. It was twilight and the weather came down and bit me hard. Adrift on the tide with the light failing, the sea and sky the one sinister colour. Paddling in near darkness, I had no idea which direction land was. I could have been heading into The Minch - the deepest water on the continental shelf. Two local boys had drowned there just a month before. I vowed if I got back to land, I’d try and capture the fear, the sense of trespassing in sacred space. Only Wagner could describe it in music, so I’ve been trying to capture it on canvas ever since.

PB: Thank you.

Extract from ‘Incandescent’

Satan Dies Screaming

(Julian Cope’s Cornucopea - Part Two)

Sunday 2nd April 2000.

I’m in bed watching Forbidden Planet when my mobile rings. It’s Liz at the Royal Festival Hall. She tells me she has been trying to reach me all day and would I like to play ‘Sleeping Gas’ on stage with Julian tonight? My silence stretches from here to the moon. “You don’t sound too keen” she says. We only met for the first time yesterday, so festival organiser Liz hasn’t quite got the measure of me yet. She’s yet to discover that no matter how positively I present, I’m as negative as an electron. I kid myself that my auto-response of Nein-Danke to just about everything I’m offered is discernment, but the truth is it’s fear. A still active phobia from childhood about being caught up in events beyond my control. I performed to an almost full house at the festival last night and no one died, so what am I scared of? Well, it’s been 21-years since Julian Cope and I last played on stage together and a lot of dirty water has flowed in and out of the mouth of the Mersey since then. So this invitation is a big deal for both of us. Because I’ve been drinking Malbec since 11am, and because I love Copey to bits for asking me, I’m absolutely horrified to hear myself say “I’ll be right over.”

Julian beams as I arrive. We hug and I scan the vast stage, wondering where the keyboard is. I’d kill to play his M400 Mellotron, but I’m anticipating some sort of high-end Yamaha portable, duct-taped to a stand. His grin widens Loki style, as he gestures to the leviathan that occupies the entire rear wall of the venue. Holy mother of Odin. Does he mean to tell me that I, Paul Simpson, two-finger Joe, am expected to play a song I haven’t heard in ten years and haven’t played in over twenty, to an audience of over two-thousand people, in a venue renowned for having the best acoustics in the world? On one of the largest and most spectacular pipe-organs-in the country? This Satanic torture device could block out the sun. It has four, five-octave keyboards, 103 drawer stops, dozens upon dozens of thankfully disabled bass pedals and an unbelievable, 7,866 individual pipes. The organ I played with The Teardrop Explodes had vibrato and an on-off button.

With the house doors about to open and no time for a sound check, Julian quickly cycles the riff on his 12-string while I find my bearings. At Ju’s insistence, his lovely sidekick, Thighpaulsandra puts black tape on the notes that make up a D chord. Julian’s saying it’s so I can see them in the gloom at the back of the auditorium, but I suspect it’s really so he has something to joke about with the audience when he next plays in Liverpool. Northern audiences are frequently regaled with his story of how, in the early Teardrop Explodes, I couldn’t play the keyboards properly. He’s right. I couldn’t. With The Fall, Suicide and This Heat as reference points, I wasn’t trying to. Anyway, right now my old bandmate doesn’t trust me not to fuck up and he’s absolutely right. There is no monitoring back here, the organ console is lit by what look like children’s torch bulbs and let’s face it, I can barely remember my way back to the hotel, let alone the upbeat and opiated kinder-drone of ‘Sleeping Gas’.

Because tonight has been sprung on me, I’ve nothing remotely suitable to wear. Julian is channelling some kind of Viking berserker meets outer-space yoga instructor look so I can’t possibly wear the tweed suit and brogues I came in or we’ll look like George Jetson jamming with Sherlock Holmes. All I have in my overnight bag is dark brown leather cut in the style of a Levi jacket and some slim, stone-coloured trousers. Brilliant. I finally get a chance of performing to an audience of thousands and I have to do it dressed like I’m in Tight Fit’s ‘The Lion Sleeps Tonight’ video.

Finally, it’s show-time. Incredibly, I’ve not seen Copey perform for over two decades, and only once as a member of the audience when The Wild Swans supported the third incarnation of the Teardrops as part of Bill Drummond’s Club Zoo shenanigans back in December 1981. Apart from a couple of his 80’s hits and a handful of songs from his Fried and Interpreter albums, I don’t know much from tonight’s repertoire. But they all sound uniformly brilliant. He’s going down a storm and the between-song anecdotes delivered in his understated Kevin Ayers-circa-1971 speak are hilarious.

A terrible thought steals into my mind. What if I really screw this up? Play some godawful howler note that makes the entire audience wince and throws Julian completely off his game? Not only could I destroy the Teardrop’s defining song but, by ruining the Festival set-closer, I could neutralise the magic of this entire event. You see, I’ve got it into my head that under the guise of entertainment, beneath the surface-layer of this festival, secret and subtle forces are at work. With support artist Coil’s hidden-in-plain-sight ceremonial magic ritual disguised as a gig earlier, and Krautrock mystics’ Ash Ra Tempel’s sorcery, Copey’s had some heavy-duty shamans collaborating on the construction of a significant cone-of-power here. And I desperately don’t want to be the one to break the spell.

Eyeing the exit doors, I consider doing a Stephen Fry. 10:05pm from Liverpool Street to Harwich – night boat to the Hoek of Holland – first train to Amsterdam Centraal. I could be canal side, drinking coffee with a selection of delicious pastries by 6 am. I’m on after the next song. In a last minute attempt to appear more Red Army Faction than Mike Nolan from Buck’s Fizz, I button up my jacket to the neck and prepare to enter Planet Cope.

“Now I’d like to introduce a very special guest. Co-founder of The Teardrop Explodes. Paul Simpson!”

Climbing the steps to the stage, I pause momentarily to draw down some protection before walking out of the darkness and into a pool of brilliant white light. Greeted by genuine whoops of surprise and thunderous applause from the packed auditorium, I smile and I wave as if this Dalinian situation were in any way normal for me. A quick ‘Let’s do this’ nod to Copey and I stride upstage in the direction of the steps that lead up to the mighty organ. But something’s wrong. Very wrong.

To be continued…

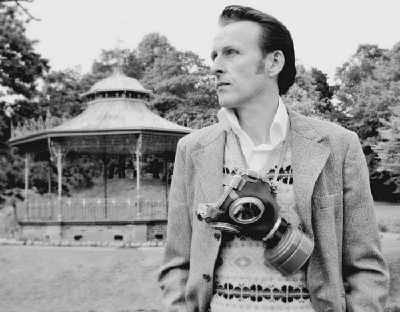

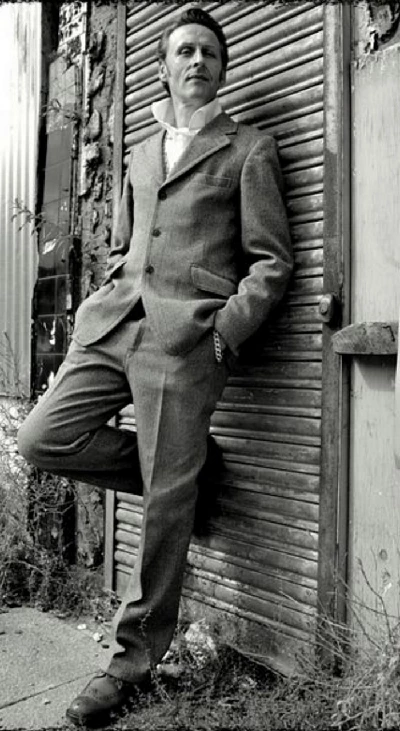

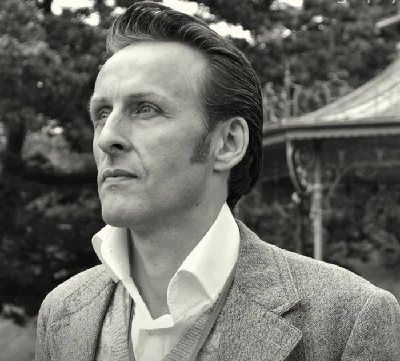

Photographs by Darren Aston. Thank you to Darren and also Mark Brend at Unbound for his help in organising this interview.

Article Links:-

https://unbound.com/books/incandescent

Band Links:-

http://www.paul-simpson.co.uk/

https://www.facebook.com/paul.simpson.

https://twitter.com/mrpaulsimpson

Play in YouTube:-

Picture Gallery:-