published: 27 /

5 /

2017

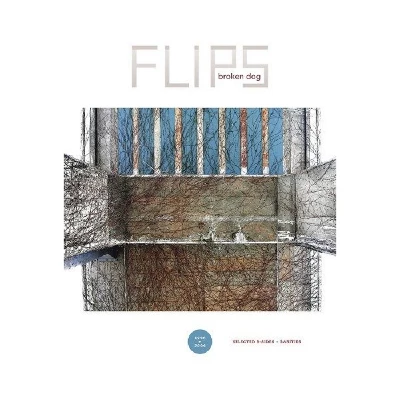

John Clarkson speaks to Clive Painter and Martine Roberts from late 1990s/early 2000s London experimental duo Broken Dog in their first interview since they split in 2004 about their career and new rarities compilation 'Flips' which is being released for Record Store Day

Article

Broken Dog were a London experimental duo of the late 1990s and early 2000s, and consisted of Clive Painter (guitar, bass, drums, keyboards, sound recordings) and Martine Roberts (vocals, bass, guitar, drums).

Their music had a haunting, ethereal sound, and was built around Painter's desolate, beautiful soundscapes and Roberts' fragile but breathy vocals, which implied a deep, unsolvable hurt.

The duo recorded five albums together, 'Broken Dog' (Big Cat Records, 1996),

'Zero' (Big Cat Records, 1998), 'Sleeve with Hearts' (Piao!, 1999), 'Brighter Now' (Kitty Kitty, 2001) and 'Harmonia' (Tongue Master Records, 2004), all in Animal, their own home studio, which also provided a recording base for many other notable bands of the era, including Tram, Monograph and Pacific Radio.

They were championed by John Peel, for whom they recorded several Sessions, but never broke into the mainstream and split up in 2004 when Painter and Roberts' own romantic relationship also broke up.

Now they have returned of sorts with 'Flips', a sixteen track compilation of

"selected B-sides + rarities" from 1996 to 2004 which combines together vocal compositions, instrumentals and four covers. It is being released on Theodore Vlassopulos' Tongue Master Records on vinyl in a limited edition of 300 copies for Record Store Day.

In their first interview since they split up thirteen years ago, Clive Painter and Martine Roberts spoke exclusively to Pennyblackmusic about Broken Dog and the new release.

PB: It seems that you had a really intense first two years - met each other, started a relationship, formed Broken Dog, signed to BIg Cat Recordings, played your first Peel Session and recorded and released your first eponymous album as well as began collaborating with Tram. Did it feel that way to you?

CP: Yes, for the first year we were getting to know each other and recording musical ideas on a reel to reel four track, and it was in the summer of 1995 that we bought an eight track reel to reel machine and decided to record what became our first album. At that time we never thought we would get signed. We were just curious to know what an album of songs by us would sound like, so when Big Cat heard the recordings through a friend and then signed us we were amazed and excited.

The end of those few years was especially intense when Big Cat basically signed us for the album that we had already recorded, released it and John Peel picked up on it. Tram and Monograph really started to take shape a while after that time. Robin and Paul were both close friends of ours, and had been writing their own great songs. We began helping both Paul in Tram and Robin in Monograph to record and develop their music sometime after the release of our first album.

MR: That was a great time. Really a dream. Right up until we got signed our big ambition had been to release a 7" single. Well, we bought an eight-track and made what was the first album out of curiosity to see what it might sound like. We gave a copy to a friend for New Year and then one day we got a call from Big Cat saying did we want to release it. Wtf! What I remember about that time was that suddenly, pretty much any gig in London, if we wanted to go, we could. Life just felt like summer all the time.

I had always been a big fan of John Peel, coming from a small town and being so into music and it providing an escape and the feeling that the outside world was a place that I couldn't wait to be in. He played 'Lullaby' while I was pottering around one evening. I remember the moment, I was so shocked, like, waaaaaooooowwwww. After that he played everything we ever released, everything. It was so special to feel that someone out there was listening to and loved our music. It added something valuable to the process of making it because then it wasn't just for us.

PB: One critic said about Broken Dog said that "the main sense here is of unease, like a disintegrating relationship or something lurking in the darkness." Do you think that is an accurate description of your music and was that what you were aiming for?

CP: A sense of unease. yes. I always liked Mark Luffman’s description of 'Lullaby' from the first album as being sung to a lover with a belly full of pills. I have always been interested in approaching music as sculpture and in leaving something of the raw material in the finished thing, a transparency, yes, and yet something more than just being able to see the process but being conscious of the piece rising up from the mess and chaos of stuff. I mean this both in relation to the textural elements of instrumentation as well as the emotion that drives the music.

So many sad songs work because they identify an emotion that we all recognise and I feel that the same is true of music which is emotionally challenging in other ways, many different ways. Besides this I enjoy the sense that we have pulled something beautiful or musical from a sea of noise. At least that’s how it feels.

MR: 'Lullaby' was like that yes. 'Baby I'm Lost Without You'. 'Where Will You Go When There's Nowhere Left to Go?' The first album played with... well, I remember when Tibo came with us to Abbey Road to master the first album, and we were sitting on the couch listening back through and at some point he exclaimed, "This is completely deranged!" and I think that was the moment when he got smitten with it. We really liked the strange atmosphere on the records of say, The Supreme Dicks and felt quite invested in exploring this kind of musical soundscape, the uneasiness of it, strange twists and turns.

I like the word deranged because it doesn't necessarily have negative connotations whereas ideas around disintegrating relationships and so on can be a bit depressing. Well, depends how it's done of course. Of course everyone has their own listening experience and I did write a lot on the sad side. But I really liked it when people found the dislocatedness kind of intoxicating in a more dreamy way. Jennifer Nine wrote beautifully about us, as well as Mark Luffman, Phil McMullen and Stewart Lee.

PB: Your influences came largely from American bands including Pavement, Smog, Will Oldham and Guided By Voices and you drew comparisons with acts such as Mazzy Star, Trespassers William and Julee Cruise. You always remained something of an obscurity, acclaimed in certain circles, but never widely known. Do you think as various critics have suggested that if you had come from the States you would have been much better known?

CP: It’s hard to say and there are plenty of American bands that remain obscure in the way that we do yet, to do an artistic endeavour because you feel that you need to still leaves you sensitive to its reception so I am sensitive to the question. Generally, and like most artists we hoped to reach those listeners that wanted to find us and perhaps turn a few other heads in the process but so much of public recognition is not simply down to your abilities but also luck, time and place. So, yes, perhaps being from elsewhere would have made a difference yet at the same time I wonder how we could be from elsewhere and yet remain the same. I can’t help thinking that we would have sounded (more) American had we been American and not had those elements of English Folk that, on occasion shines through what we do.

It is true that at the time of our record releases there was a focus on bands that fitted into the so-called Britpop scene and perhaps there was less time in the media devoted to bands like us. Whereas in America there was more focus on maybe the alt-country and lo-fi scenes and less focus on British bands, so perhaps it was a case of right time, wrong place, which we could only put down to luck.

I do think we were lucky to have existed when we did as I’m not certain we would have been signed at all had we been born twenty years later.

MP: I like what Clive says. I have something to add to it. I actually think that if we had really been able to cut it live, we would have been better known. At that time, to get yourself known, to be seen, for people to buy your records, you had to be playing live. That was always how Big Cat saw it, and subsequent labels, though they weren't so pushy. Not that Big Cat were generally pushy: we were very lucky that they largely left us to our own devices.

But the live thing was difficult. You really needed to do it and we were really a studio band. In a studio, it doesn't matter if your voice is quiet, but it is a problem in a live setting. My voice was just so quiet that playing live it was impossible for the band to crank up the volume and give it the welly, the dynamic and the punch that would have really delivered the music. The other thing was, I suffered so much from stage fright that I would be sick for days before each gig. When it came to the gig, when I had to go up there I didn't find any means to cope with it, I just wanted to run away, I was just so uncomfortable.

In this sense I think that I really let us down. It must also have been uncomfortable for an audience to witness that. I always had this dream of wouldn't it be great if another band did a 'Broken Dog' gig instead of us!

PB: Both 'Flips' and 'Fragments', another collection of Broken Dog rarities, came out on download last year on your own Magnetic Ribbon Recordings. Hw did the idea of doing a limited edition release of 'Flips' on vinyl for Record Store Day come about?

CP: I met up with Theo from Tongue Master Records and gave him a copy of 'Flips'. Theo had released our last album 'Harmonia' and was always interested in what we had done. When he expressed an interest in pressing vinyl copies of 'Flips', of course, it seemed to us a great idea.

MR: Yes, Theo loves his vinyl so we are lucky to have beautiful vinyl copies of 'Flips' thanks to him.

PB: 'Flips' sounds remarkably cohesive considering that its material was recorded over an eight year period. It could be a sixth studio album. How much of it do you think this is because of Alex Wharton's mastering of it in Abbey Road and how much of it was down to the fact that all Broken Dog material - I think -was self-recorded in your own home studio Animal?

CP: I’m glad you feel that it could be a sixth album. And yes it was all recorded in our home studio, Animal. In setting up Animal we couldn’t help but setup a ‘sound’ as we always used our drum kit, guitars, keyboards and amps, and once we’d got the sound we were after we mostly left things mic’d up as they were so that we could focus on playing rather than the technical stuff. I romantically like to think of this as being similar to the Motown studio setup.

Alex at Abbey Road did a great job but credit must also go to Steve Rooke at Abbey Road who had mastered many of the songs when they were originally prepared for CD single release back in the day and the masters of which were used for 'Flips'. Steve has now retired but had mastered all of our albums as well as Tram’s 'Heavy Black Frame'. So, yes, they are both important as is Abbey Road itself. It has always been lovely to have our songs go through Abbey Road on their way to the outside world. It feels like the best possible send off and, of course, a great place to work given its importance in popular music history.

PB: You collaborated and indeed played with various other experimental bands of the era including Tram, Pacific Radio, Monograph and latterly the Real TUesday Weld and the 99 Call, and Animal provided a base for a lot of all those bands' recordings. Did you see Broken Dog as being part of a scene?

CP: There was no intention to create a scene but it did feel, in some small way, that something formed around us and our friends of the time. I was conscious of this at the time and it was pleasing. It felt good to be a part of something bigger than what we were creating in isolation. I’m sure that lots of artists feel the same way. And these things do happen best when they emerge organically, when they emerge because artists like to hang out with other artists and so form a community of like-minded souls.

MR: Maybe rather than a scene it was more like being part of a time. It was really exciting to be creating and playing stuff to friends who would share what they were doing with us too. That's how we ended up playing on so many other people's records. You just naturally exchange ideas and contributions. It's like an ongoing dialogue. It was very energizing, very inspirational. The network just organically grew as friends and then friends of friends would get in touch and come over and record stuff, or master their recordings. I loved it when people came over - even when the bathroom was requisitioned for backing vocals - and sometimes I cooked for everyone at the end of the day. It was a wonderfully convivial existence.

PB: You include covers on 'Flips' of Big Star's ‘Big Black Car’, the Kinks' ‘Lazy Old Sun’, the Left Banke's ‘Sing Little Bird Sing’ and the Band's ‘The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down’. They all sound different and build on from the originals. What was Broken Dog looking for when it decided to do a cover?

CP: We always looked for songs that we could do our own thing with. But for each cover it was different. With 'Sing Little Bird Sing' I was so taken with the arrangement that I wanted to get inside it and work out how it was put together.

We did the cover of 'The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down' as a birthday present for John Peel. On his 60th birthday John’s producer Anita Kamath secretly sent out a list of his favourite songs to his favourite bands of the time, asking each to choose and record a song for a surprise birthday CD. And so we choose to record 'Dixie' from the list. If memory serves I think we chose it because it felt like the least likely song that we would pick and that in itself might appeal to John. After all it was his birthday.

Across all the covers that we have recorded is an attempt to embrace the music as if it were (respectfully) ours all along.

MR: Yes, it's like we would be struck by a song we loved and could see that we could do our own version of it while keeping the spirit of the original alive. Doing the cover for John Peel was probably the closest we ever kept to the original version of a song. It felt a bit like we were treading on hallowed folk rock ground, but yes it was fun to try something so different for us; a true surprise like Clive says.

PB: How did the songwriting in the band work? Did you, Martine, provide most of the lyrics and Ciive the music or did it work in another way?

CP: We never had a strict way of writing and we both had a go at everything, but over time a system evolved where Martine would pen something to a few chords and then I would embellish and expand the chords into something more expansive and textural. That’s certainly true for quite a few songs yet there was no limitation in production, and so both Martine and I would play a full range of instruments and quite a few songs were born of improvisations.

MR: Yes. A favourite trick was when we had worked on embellishing the original arrangement, and then Clive would suddenly eliminate the foundational structure if you like, and we'd be listening to something with a completely different character, some floating elements all hanging together with an unexpected integrity, something unusual and magical that we couldn't have dreamed of assembling as it stood. When it worked, it was gobsmackingly exciting, and we would navigate this new world as a new starting point. This is an example of the sculptural element of composition that Clive talked about earlier. It was refreshing because it was then as if the song had a life of its own and we worked to simply serve that, to listen for what was right.

We would spend days and sometimes even weeks listening and even straining intently to know what a song was asking for! I would say sometimes we just felt like the vehicles for its existence in the world: we just made the music 'visible'. 'Light Passing Through' is a good example of this approach.

Clive played most of the instruments it has to be said. I loved to play bass, but what made it onto the recording was simply a case of whose ideas were the best for the song. Clive is one of those people who can pick up an instrument he has never encountered and learn to play it in an hour. I liked to have a go at stuff. In our version of 'Lazy Old Sun' I chip in with a Turkish clarinet we had borrowed from somewhere at the end. Just one note repeating. The reed was chipped and to get a sound out of it I was blowing so hard I thought my arsehole was going to go flying across the room. If you listen you can hear the effort in the blow, and we kept it because it made us smile.

PB: You recorded a prolific five albums in ten years. You said, Martine, that you found playing live difficult. How much live work did Broken Dog do?

CP: Not a great many gigs. We played quite a bit at the Garage and we were on the bill of the Terrastock 3 festival. Being primarily a duo meant that we would mostly borrow musicians from within our group of friends which was always fun and to whom we were always grateful, but it did mean that we never quite solidified as rock solid live act. To be honest playing live was never something that we were very comfortable with, although a few moments did shine through our reluctance.

MR: I think it's a shame now, because I'm not so shy anymore! But there is nothing to be done. I am really proud though that we supported the Red House Painters.

PB ;You broke up after 'Harmonia' and your own relationship ended. It seemed at the time that you just drifted away. Do you see 'Flips' as putting some kind of seal and finality on things?

C: Yes I did. When Paul Anderson (Tram, the 99 Call - Ed) and I set up Magnetic Ribbon the plan was for it to be a vehicle for our new records along with records that friends of ours had put together, but also we wanted to release the archive of past Broken Dog and Tram records as downloads seeing as the rights had returned to us. So for me 'Flips' has been a way of making all those songs that weren’t on album releases available in the same way. On a personal level releasing both 'Flips' and 'Fragments' has helped me to gain a sense of completeness to this era in my life.

MR: I'm so glad we are releasing this stuff, and very grateful to Clive for all the work he's done trawling through our mountain of outtakes and so on! It does feel like something's completed: all the stuff out there.

PB: Martine, your last recording was in 2010 on the 99 Call's first single 'Last Days'. Are you still involved in music these days?

MR: I'm not but that's not to say I never will be. These days I love it when I come across a drum kit and can have a good bash. That's not very often because I don't have a base and wouldn't really know how to encounter musicians in new places. Actually I did play drums for a gig for a friend Laurie McNamee's band a few years ago and that was very satisfying. So cathartic. I do love singing and sing a bit for myself in the mornings when I wake up. I dance a lot these days. That was off and on my other thing. That has come back and that's really where I'm at right now, celebrating life through wild dancing!

PB: Clive, you did a few gigs with Madam as their guest bassist. What else have you been doing musically in recent years?

CP: I’ve been doing some work with Paul Anderson on the 99 Call which is an ongoing thing. And as with 'Fragments', I, along with Paul Anderson have embarked on a similar trawl through the archives with the hope of releasing some lost Tram recordings. And apart from that I have begun a new instrumental project called Dolorous Interlude and hope to release some material soon.

PB: Thank you.

Article Links:-

http://www.tonguemaster.co.uk/

Band Links:-

http://www.brokendog.co.uk/

https://www.facebook.com/brokendogtheb

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Broken_D

Play in YouTube:-

Picture Gallery:-