published: 27 /

5 /

2017

Guitarist/singer-songwriter Mark Farner, former front man of Grand Funk Railroad and solo artist, discusses his musical legacy and desire to connect with veterans and Native Americans

Article

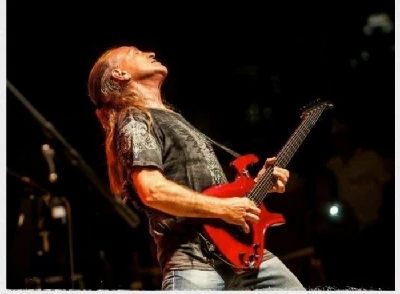

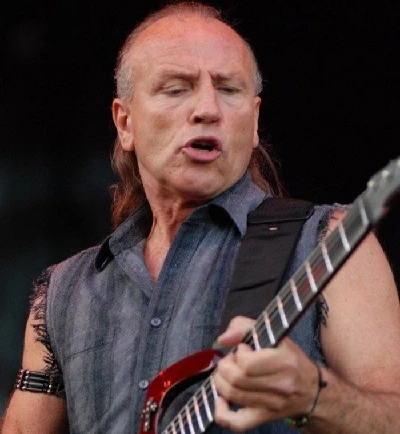

Mark Farner is essentially timeless. His voice remains as pure and stealthy as it was when he tore the house down during the 1969 Atlanta International Festival as the front man of Grand Funk Railroad. (He rejoined the band in the 1980s and 1990s, and also forged a solo career.)

Farner's toned physique belies years of on-the-road wear and tear and his spirit glistens, whether he is talking about his steady flow of established and new fans or those in our society that are too often marginalized.

Farner is a no-nonsense Midwestern musician. He hails from Flint, Michigan where he says his muse appeared courtesy of Motown and several seasoned crooners and instrumentalists.

He learned early on that fans relish a visual display. His stage appeal owes much to the early dance moves that he embellishes on in his second Pennyblackmusic interview with Lisa Torem.

There seems to be no fourth wall here. Farner looks just as jubilant signing autographs after a show as he does onstage. He sums up his love for his audience with a few choice sentences: "Just like when you hold a baby, the love transfers. I feel that when I'm on stage from the audience."

That love is also evidenced in the timeless resilience of his many hits. 'I'm Your Captain' (Closer to Home), 'We're an American Band', 'Some Kind of Wonderful' and a revised version of 'The Loco-Motion' still force audiences to their feet and relay poignant messages.

Farner, also known as "The Rock Patriot", seems to take that title very seriously. During a recent performance, he quietly announced that he would be dedicating a special song to a fallen lieutenant. In Mark Farner's world, heroes are simply not forgotten. His goodwill and sincerity move us as much as his melodic solos, clever licks and raw phrasing.

PB: I had the pleasure of seeing you with the N'rg Band in St. Charles, Illinois recently. What are the origins of this band?

FN: We started back in 1991 and obtained Hubert Crawford as drummer, and Dennis Bellinger, the bass player, was actually on a couple of Grand Funk albums and toured with us when Mel Schacher, the original bass player for Grand Funk, was afraid to fly – he didn't want to fly anymore, so that was a couple of years he took off, but then he got back in the group. But Dennis did the two albums and vocals and bass, so he knows all the Grand Funk stuff and kind of was weaned on that stuff, so he makes a good fit and he's a Flint boy.

Karl Propst, the keyboard player, is an Atlanta, Georgia native, but was transplanted to the North, like many of the Southern musicians that came North, but fitted in really good because he has devoted himself to the keyboard and he spends most of his waking hours fooling around, either fixing one or playing one (laughs).

PB: You spend a considerable amount of time greeting your fans after many of your shows.

MF: Part of what completes the show is to shake hands with people, look them in the eye and say thanks for supporting my music over the years. Once in a while you'll hear a short story from someone and it just makes your day. A song can change somebody's life, change the direction from going into darkness and turning that sucker around, bringing it back into the light and so I'm very grateful to give credit to the spirit that brought that. It makes it a complete show when I get with the fans and give autographs and what have you.

PB: Some of the early Grand Funk Railroad tunes like 'Time Machine' and 'Mr. Limousine Man' suggest a deep reverence for the blues.

MF: Oh, yeah. R & B was bred into yours truly, because that's what I listened to. CKLW, out of Windsor, Ontario, Rosalie Trombley was the program director there, and she played a lot of the Motown and R & B stuff. It was great music to dance to back in the day, in the '60s when I was dancing with my sister. We'd go to these dance contests at the National Guard Armory, Daniel's Den and Sherwood Forest. There were a lot of places where we would go and dance; the Russellville Dance Hall, and there were dance contests.

There weren't too many guys in the contests, so my sister and I would dance. We already knew the moves and what we were going to do and we won a lot of dance contests. My mom taught both of us at the same time. We learned the same moves and did it. A DJ used to set up his system and play records— they called them sock hops, and a lot of times, they would be playing, like at the National Guard Armory, and a mixed crowd in Flint, Michigan, of black and white, but everybody got along great because we all had this music in common. We all loved this music. That's part of the culture that I was raised in, no discrimination what so ever.

PB: 'Heartbreaker' was the first song you ever wrote.

MF: It was very special because I was with Dick Wagner, who was guitar player for Alice Cooper, and The Frost was one of the early renditions of his band, but the Bossmen was the one that I paid particular attention to — they were a show band. I loved to go see those guys because they were very entertaining and part of my learning curve was watching those guys and trying to introduce that was very entertaining as a spectacle, not just sonically, but with the eyes, to express as a kind of theatrical art.

So I was talking about this with Dick Wagner about two or three o'clock in the morning. We would always set up in his apartment and play electric guitars, not plugged in — very softly. And he would show me chords and I told him one night, Dick, I don't know how the heck you do it, you write all these songs, where do they come from?

"They come from within", he said. He said, "Mark, you can write music." I said, "I can?" The light went on again, so he went to bed and I stayed up and started playing the chords to 'Heartbreaker' and then I started writing the words down.

(Mark sings) "Once I had a little girl". It just flowed that night. That was my first song and when he got up in the morning I couldn't wait until he got out of bed so that I could play him this song. And I was jamming in the group, The Bossmen, at the time. I was playing rhythm guitar and Wagner says, "Dude, let's put this song in the set and see how people like it." So I played it with the Bossmen before I played it with Grand Funk, like two years prior, and the people loved it, and he said, "We'll keep it in the set. Man, people really loved that song."

So that's how it came about and I give Dick Wagner the credit for inspiring me to be a songwriter.

PB: Did what you learned from writing that first song transfer into writing subsequent songs?

MF: Oh, yes.

PB: Do you generally start with a melody, a riff, lyrics?

PB: It's been mostly a riff or riff-driven to create a feeling and it depends on whether that riff is in a minor key, a major key or in a seventh or whatever. It has everything to do with the mood that the music will be created in. Most of the time it's like that, except for 'I'm Your Captain'.

I got that lyric first. I didn't have a clue to what the music was for 'Closer to Home'. But I had prayed one night: "Now I lay me down to sleep, pray the Lord my soul to keep" — this thing my mother had taught all of the six kids and I would say that every night for the fire insurance, just in case (laughs), and I put a P.S. at the end of my prayer and I asked God to give me a song that would reach and touch the hearts of people that God wanted to get to, and I got up in the middle of the night, after I'd been asleep for an hour or so, and I started writing these words down. I

But I leave a legal pad next to my bed, and a pen because I wake up and I have words on my mind. They might not be a song or even a poem, they just could be words, but they have to come out and so I write them down, so it wasn't unusual for me to wake up and write something down, but in the morning when I had my coffee fixed and I was looking at the horses out in the pasture, I had a George Washburn American-made, flat-top guitar, that was parked in the corner of my kitchen on a guitar stand. I grabbed that and I started playing (Mark sings), the introduction lick to 'I'm Your Captain' and I thought, 'Wow, that's pretty cool'.

I started to play the D chord and then I reached over, and instead of taking my whole hand and making a C, I just reached across and grabbed two notes to make it a C, with a sustaining G on the top of it, which gives it a very different kind of a feel and that was the first time I ever even played that chord, but it stuck, and I thought, Wow, this feels really good. When you discover something as a guitar player, you've got to wear that thing out so it gets into you, so I played it time after time after time, and I was just feeling good.

Then I thought, hey, maybe those words are actually lyrics to the song. I didn't actually think so when I was writing it, but I grabbed them and I started singing – the melody came right away and I took it to rehearsal that day and the guys, Don and Mel, both said, "Farner, that song's a hit," and they were right.

PB: What are your memories of playing the 1970 Atlanta International Pop Festival?"

MF: Getting there was a real challenge. A friend of ours loaned us his van and a driver. We rented a U-Haul trailer to put our equipment in and put it on the back of this van and we were going down the road heading to the festival— this was before the I-75 was finished in 1969, so we were on the back roads.

I was riding shotgun and the guy that was driving, Jimmy, he had been awake all night and this was early morning. I look up and see the sign that says I-75 and it's pointing to the right and I said, "Dude, I-75's to the right", and he tried to turn right, but he was going too fast and he was too far past it and he flipped that trailer over, down through the ditch with all of our equipment in there. The transformers were torn from the chassis and the amplifiers. It was a mess, but we righted the trailer and we nursed down the road to the following exit which had a trailer place, thank God. We traded it in on a good one, because it was insured and we took off and made it to Atlanta.

But when we got there, immediately, our roadies had to start soldering wires together. It was miraculous because these great, big, heavy transformers that were ripped from the chassis were sitting on top of the amplifiers instead of inside them. They just ran them up on top and said, "Leave it the way it is because it's working".

We went up there and we played our first song and I kept thanking God. I just prayed that we could make it through the set and we did. There were about 180,000 people in the audience. I only saw between the cracks backstage the first couple of rows and didn't know how big this audience was. I could feel it from the energy but until we actually had the vantage point of going twelve feet above their heads, I said, "Holy Crap".

As soon as I saw how many people there were, I told my head roadie at the time, "Look, man, I've got to pee so bad". Like a race horse. They loved us though. We played our original material and then we did an encore of 'Land of a Thousand Dances', the Wilson Pickett rendition.

Then I took my guitar off and I danced around the stage. I was really having a good time, but I was so wet from the sweat - I had this brand new see-through Paisley shirt on and it was sticking to me so bad, it was restricting my movements. I just grabbed the front of it and I just ripped that thing off and the crowd went nuts. And I thought, Well, there's a new one right there. I learned that trick and from that point on I just went on shirtless or wore a vest because I knew I was going to be sweating and I knew when I took my shirt off or my vest off that the audience was going to dig it. I was the first bare-chested rocker.

PB: How long did it take for you to develop your own style?

MF: I had my own style right from the get-go and that was all influenced by the R & B. There's a lot of rock'n'roll out there but not much that's R & B influenced. In fact, in the early days, the audiences at our concerts would be half-black and half-white and that's the way it was for two or three years. And now I hear from friends that are musicians in the industry, "You guys are the only white band that we would listen to". So that was quite a feather in my cap because I was influenced by Howard Tate, a black vocalist from the '60s. Aretha Franklin copped some of his stuff, and Stevie Wonder. There's not anybody that has actually made top-ten music that hasn't been influenced by this guy.

I was introduced to Howard by the album, 'Get It While You Can'. We were at WTAC in Flint, Michigan and the disc jockey said, "Hey, on your way out, you guys, there's a few albums. We're going to throw them in the dumpster, so if you want any of them, take them". I just filed through there and I grabbed that one album, just because it caught my eye and I was so glad, when we got back home and put that thing on the record player. Wow. That music really touched my heart and I said I want to sing like this guy. So I patterned my vocal style after Howard Tate. Of course, I had my own style, but he's in there. He has this way of communicating and getting up there in the high notes and I know because people like to hear me sing the high notes. I see that reaction from people in the crowd. It helps the enthusiasm.

I took some of that from Howard Tate and I took some of Jimi Hendrix's playing, some of Jeff Beck's playing, Rick Derringer and Steve Cropper, from Booker T and the MG's, a very soulful cat. Those were my guitar heroes, but Jimi Hendrix was number one.

PB: Producer Todd Rundgren worked with Grand Funk on two major albums.

MF: It was a great experience and a great learning curve. I don't think he's ever been serious a day in his life. That's just the kind of guy he is. We were recording at a Grand Frunk studio, The Swamp, across from my farm and there's 110 acres on one side of the road and a swamp.

So I'm walking back from the farm house and it's a sunshiney day. I could hear the guys in the parking lot. They were out having a smoke and just talking and so I started singing, 'Everybody's doing a brand new dance now'. They started doing the background, 'Come on, baby, do the loco-motion'. Rundgren comes walking out of the studio and he says, "Guys, guys, guys, what the hell is that?"

We said, "That's Little Eva. That's 'The Loco-motion'." He said, "We've got to do that song right now. Everybody get in that studio and then we're going to have a party out of this thing." We did the 'Loco-motion' and it was a party for us and it really transferred into the grooves because the people loved that song and it went to number one.

PB: You have done a lot of outreach with American veterans and Native American communities. What have you gleaned from these experiences?

MF: In the Native American communities, there is a lot of alcoholism because the Native Americans were taken from their beliefs. They were removed from that element and they were forced to learn the alphabet. It was forced on them in order to become part of this civilized society, but the firewater... I'm part Cherokee myself. It helped the white men that were destroying their culture to take their land from them. They'd get them in a drunken state of mind and they'd say anything, do anything because it doesn't take much, it just takes a little bit. The first thing alcohol affects in anyone is our judgement, so when you're not ready to have a sane recall, to not have something based on a solid yes or no, this is what happens.

I try to minister with love because I'm part Native and I try to minister to the young people. They want to know how I put up with it and I deal with it. For me, it's been an eye-opener, but also, it brings me closer to the land. It brings me closer to the red road because, if the Jesus that I think he is, the miracle confirms the truth of his words.

PB: You dedicated a song to American veterans at your concert.

MF: The veterans have always been my heroes. My dad was a World War II vet. He returned with four bronze medals. That means that he was in four major battles and a lot of tank drivers didn't get to see their second battle. It was a dangerous position to be in.

My mother was the first woman in the United States to weld on Sherman Tanks in Flint, Michigan at Fisher Body Tank Plant, and that was the tank that my dad was driving. That is in my bloodline. It's in my history. I've been fed that by my mother's words. I was nine years old when my dad died. With a fellow fireman, he died in a train wreck. It killed them both instantly. Then my mother raised us with a stepdad.

But when I had the opportunity to get in front of a bunch of soldiers. troops out in the field, I never felt better appreciation from any audience. They really, really, really loved that you were there for them, that you came to where they are.

They love it. There's not a more adoring audience than our troops and I always give kudos to the veterans and when I sing 'I'm Your Captain', I dedicate it to the troops. I thank the veterans for their participation and I want them to know that we're not going to forget them, that their passion and their reason for going. That is the deepest part of a person. They're driven by a love for God and their country and you can't get closer than that.

But the media never talks about our soldiers. They never talk about the families that are left without this loved one. They return without one leg or without an arm. They just keep getting neglected and the Veteran's Administration keeps putting them on all of this medicine, this mood-altering medicine, and it just helps them into their grave, faster.

I am now the honorary chairman of the American Veteran's Association. We are in 32 states and in 32 veteran's hospitals. And our message is that we won't ever forget you. We will not let the world forget you. We will not let you live for not. You have something to be proud of and we're going to help you realize that. This is my association with the brothers and sisters who serve.

You just can't get better people. There are no better people on this earth.

When my dad died, it was the largest funeral that the city of Flint had ever seen. There were more people in that funeral procession than for any of the political figures that had died in the town. It was overwhelming for me. My dad had touched this many people and they loved him, but he was a man of love. He and my mother, they were a picture of love.

PB: 'Sin's a Good Man's Brother' was covered by Monster Magnet. The strength of the riff and the lyrics shine through even though the band imagines it through alternative eyes. Have you heard that cover? Which covers have you heard that echo the truth of your originals?

MF: The Jayhawks covered 'Bad Time'. I heard that version and I thought it was very interesting. Like you said, the licks are there and the melody is there. That's the highest compliment; to imitate what they have done.

PB: 'Bad Time' was written during a stressful time, but it's not a song that brings us down. There's a sincerity that comes through. A message.

MF: That's turning the tide. When a tough situation is on us we feel the weight of that in our hearts and in our head, especially when it's on your heart, it can't help but obstruct what's going into your head. A lot of confusion and turmoil goes on, but when you determine to focus in the midst of this kind of turmoil, it's so abstract compared to the norm of your life, that you just have to tell yourself, I'm going to use the energy from this because it's my energy, and it's mine to do with what I'm to do, and I'm not going to allow myself to go down in the doldrums, so as you're circling the drain, you cool out and pull yourself out of there.

That's what the song did for me. It helped me get out of that place in my mind, but also to express it in a way. I believe it's a beautiful way for someone to express a hurt or an emotional struggle that they're having, and it seemed as if when I was writing this song, it would help me resolve, get it off my chest. A lot of times what we really need to do is express it, even if there is no one in the room with us. It spreads it out - we hear it back in our ears, just thinking about it. Taking those words deep within our heart will change things. That's the way it works. It just is.

PB: The audience at The Arcada was impressed with your vocal resilience and overall stamina.

MF: The big part of what people see, when they come to see my show, is my experience in my life, all added up, all tolled up to now and part of that has been that when I had my pacemaker put in, I died. I was in Heaven twice and had to come back. And when I knew I had to come back to my bone suit, I was in such a place. Human words can't even begin to express or define or paint a picture of Heaven.

But I was in a place where I had the recollection of the Earth Years. I knew all things and I knew that I had been here, where I was, that I'd been there before and I was back to where I started from before the bone suit experience.

Then when I started hearing the voices of my wife calling me, and the doctor, and I was talking to her and he said, "We've got him back twice. There's no guarantee we'll get him a third time. We have to get him to O.R. right now."

They got me back to the operating room and everything but when I knew I had to come back, I said, "Shit." I was really bummed out because it was so good over there, but I know that's part of who I am now and what people will encounter with me is that person that made that trip, and I have no fear of death what so ever. I have love in my heart for truth and I know the truth is what makes us free.

My relationship with my audience, my songs, is embellished by my trip.

PB: What advice do you have for young people entering the music industry?

MF: I hope there's going to be more women because we definitely need more female energy to balance our planet. As a Cherokee man, we esteem our wives to be equal to ourselves. I've been married to my wife for 39 years, and for the young musicians coming up, they've got to walk by faith and not by sight because the world is a mirage. What we see with our eyes; there really isn't anything that there appears to be and so to get close to your passion, if the passion of music is driving you as a young musician, a young woman or young man, then you need to shut off the rest of the world and get close to your instrument. Get close to your voice where nobody else can hear you and just sing to yourself. Sing until your heart feels good.

I used to cover my guitar with the covers that I was lying in bed with. When I got up in the morning, I would peel back the covers, get that guitar off my chest and start playing it again.

I was driven and I believe that that kind of passion, if you feed it, will be productive. Even though the record companies are not like they were when I was coming up--you don't have the ability to walk into a radio station and say, hey, will you play this? That's not going to happen, but it did when I was a kid.

But those things are controlled and contrived now. So in spite of this, we have to find our heart in it. And if what's driving you is the passion for your music, don't let anything upset you or distract you. Follow your heart and put your whole self into it. That's how you get good at it and that's how you get something out of it.

PB: Final question. What are your touring plans for the coming year?

MF: We're doing South America: Santiago, Chile, Brazil and Peru, and we're also going to Guam and the Philippines in May, so I get to see some more of our troops over there.

I'm going to go boldly with love in my heart. I'm going to entertain and provoke people to think about this life.

PB: Thank you.

Band Links:-

http://www.markfarner.com/

https://www.facebook.com/Mark-Farner-1

Picture Gallery:-