published: 15 /

5 /

2016

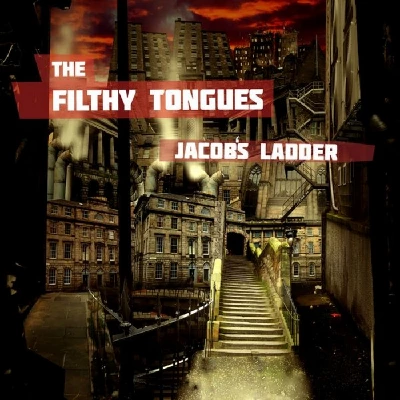

John Clarkson speaks to Derek Kelly, the drummer with Edinburgh-based alternative rock trio the Filthy Tongues, about 'Jacob's Ladder', their debut album, which examines the hidden under surface of their native city

Article

Edinburgh is a city of contrasts. For all its magnificence – its castle poised over its centre; the tall, beautiful buildings of the Royal Mile; the spacious gardens, hills and parks; its four week long summer festival –there is a dark underbelly. In the 1980s it was the AIDS capital of Europe and it is a city that has had over the years major drug problems.

‘Jacob’s Ladder’, the intense debut album of Edinburgh alternative rock trio the Filthy Tongues, reflects on this duality. The opening title track takes a brisk look at four hundred years of history - the regular hangings that used to take place in the Grassmarket of the Old Town, the occasional riots in its streets, and the contrast between Calton Hill which offers one of the most splendid views of Edinburgh and the for centuries down-at-heel sea port of Leith with its whores, drug addicts and alcoholics.

‘Long Time Dead’ tells of a group of chronic junkies, who despite having lost limbs to their habit and annihilated their long-term health, maintain a carefree nihilism about their choice of lifestyle. ‘Bowhead Saint’ and ‘Children of the Filthy’ meanwhile reflect on the differences between Edinburgh’s corrupt and self-serving past and present political and religious leaders and its often dispossessed regular citizens.

Martin Metcalfe (vocals, guitar), Fin Wilson (bass) and Derek Kelly (drums),

the trio that make up the Filthy Tongues, have played in Edinburgh bands together for thirty years. Their first band Goodbye Mr Mackenzie is now most famous for featuring the young Shirley Manson on keyboards, but were a huge draw in Scotland, touring heavily there and having local hits in the late 1980s and early 1990s with singles as ‘The Rattler’, ‘Face to Face’ and ‘Goodwill City’.

Their success in Scotland, however, did not transcribe over the border, and their 1989 debut album ‘Good Deeds and Dirty Rags’, recorded in Berlin at the time the Wall came down, and ‘The Rattler’, their only Top 40 hit, both just scraped the bottom end of the charts. They were transferred across EMI, from one major label there Capitol to another Parlophone but when two singles, ‘Love Child’ and ‘Blacker Than Black’, also failed to chart nationally were dropped.

They signed to Radioactive Records, an indie offshoot of American major MCA, for their second album 1991’s ‘Hammer and Tongs’, but when that album was also not a success outside Scotland, were again dropped. Their 1994 third studio album, ‘Five’, the first to feature Manson on lead vocals on just one song ‘Normal Boy’, came out on their own label Blokshok Records.

The group re-signed to Radioactive Records under the name of Angelfish which featured Manson on vocals and Metcalfe, Wilson and Kelly as backing musicians. This new project released a self-titled debut album in 1994, which was produced by Talking Heads’ Chris Frantz and Tina Weymouth, yet was short-lived, breaking up later that year when Manson left to join the bestselling Garbage. Metcalfe, Wilson and Kelly resurrected the Goodbye Mr Mackenzie moniker for one last album ‘The Glory Hole’ (1995,Blokshok Records), but, with Metcalfe’s long-standing addiction to drugs and alcohol having escalated beyond control, that group too finally broke up.

After a long hiatus in which Metcalfe beat his addictions, the trio formed the Filthy Tongues. The group soon mutated into Isa & The Filthy Tongues when Metcalfe’s American girlfriend and now wife Stacey Chavis joined the band on lead vocals. Isa & The Filthy Tongues’ released two albums, ‘Addiction’ (Circular Records, 2006) and ‘Dark Passenger’ (Neon Tetra, 2010), before Chavis decided to take an extended break from the band to focus on her other career as a yoga teacher.

In a rare interview, Derek Kelly, who is now based in London, spoke to Pennyblackmusic about ‘Jacob’s Ladder’ which he kickstarted, and his long musical career.

PB: How did you write and record ‘Jacob’s Ladder’? You were the main songwriter rather than Martin Metcalfe this time on it.

DK: It was, to be honest, written and recorded in a way that was not very different from a lot of the other albums that we have done. We write in something of a haphazard way. By the time the songs were finished and everyone had got to put their imprint on it, I wouldn’t say that I had written more of it anyone else. I dictated more of the direction at first, but by the time we finished I would say that we had all had had pretty much an equal input.

PB: You’re not from Edinburgh originally. You’re from Bathgate, which is twenty miles outside of it, and you have been based in London now for about ten years. 'Jacob's Ladder' is very much about Edinburgh. Do you think that you were able to able to get a better perspective of it by being away from it and not there?

DK: It’s possible. I don’t think that I have divorced myself that much from it because I have always come back regularly. We have always made music together, and there was always things going on in Scotland that I was coming up for. It is hard to say. We did talk more this time about the album that we wanted to make than we usually do. We usually write songs and see where the direction takes us, but this time we had more discussions about where we wanted to go with it lyrically. I don’t know why that was. It possibly tied in with the Scottish Referendum. It perhaps honed in us a sense of identity and place, and created for us that kind of environment to question what our place was in Edinburgh and Scotland.

PB: Edinburgh is seen as a beautiful and culturally rich city, but there is a darkness there as well beneath its surface appearances. If you look at many of the writers that come from Edinburgh, from James Hogg and Robert Louis Stevenson to more recently Irvine Welsh and Ian Rankin, they have all picked up on that. You seem to be following that tradition.

DK: Martin and I came through from Bathgate when we were seventeen to Edinburgh with no great expectations, other than to have, like anybody that age, a good time. It was a big city for us. For me personally, and I can’t speak for Martin, I like to know where I am and I like to know the story of

the place that I am in.

The really interesting thing about Edinburgh is the dark side of it and the fact that it has this strange duality. There are all the obvious touch points, Deacon Brodie, the Old Town, the New Town, and you mentioned Robert Louis Stevenson and ‘Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde’. For us all that stuff has always had more of an attraction. There is a melancholy and a danger but also a charm to it.

PB: If you go back to Goodbye Mr Mackenzie, you were tapping into that dark side with songs like 'Goodwill City', which was inspired by a local Tory councillor saying that Edinburgh AIDS victims should be all put on oil rigs. It seems that with 'Jacob's Ladder' you have expanded on what you were already saying in a less direct form in Goodbye Mr Mackenzie.

DK: We have always dipped in and out of Edinburgh because there was so much richness in the stories there for us, but it has taken us until now to have the clarity to write about it in a bigger and slightly more coherent way than we did the late 80s.

When we came to Edinburgh in the 1980s, Edinburgh was a place that had a past, but it didn’t really feel that it had a future. There were really big gaps in the Royal Mile, this thoroughfare that is flaunted throughout Europe as being one of its most beautiful streets. A lot of it was derelict. You go down to where the Parliament is now, and you went there at night and there was nobody there. It is a very different city now compared to what it was then, and a lot of the things that we are writing about on 'Jacob's Ladder' are from then. You sometimes need twenty-five years to reach a perspective on things.

PB: Was ‘Long Time Dead’ inspired by real-life characters?

DK: Yes (Laughs). I think it pretty much speaks for itself. The Mackenzies’ background is well documented. There were periods during the band’s career in which a lot of it involved that kind of behaviour or us being involved with those kinds of people.

It is hugely uplifting at times. It always seems like we are painting a dark picture, but it is in the way that Leonard Cohen is sometimes seen to be depressing. I find the opposite. I find it is really uplifting to write about a lot of this stuff. Those are though pictures, fragments of situations that people in the band have found themselves in.

PB: Who are ‘The Children of the Filthy’?

DK: It is mixed up with other things as well, but we have a loyal group, a sort of core who have supported us through the times that we weren’t doing very much. If we decided to put our head over the parapet and to play a gig or release a record, we always had a really fantastic core of people that helped and supported us, so they wound up in there as well because they always helped us on a – a horrible phrase to use – our journey through Edinburgh

PB: Who is Gerry Gapinski who did the art work?

DK: I actually spotted Gerry’s artwork on Avalanche Records’ Twitter feed (Long-standing Edinburgh record store – Ed). He does saw these really dystopian pictures of Edinburgh and that really caught my eye. I like that kind of artwork anyway, things that are not in straight lines, that are not quite right, and he had taken parts of Edinburgh and made it into this Dickensian sort of dystopia.

It stuck in my mind and I said to Martin, “Go and check this out.” When we started thinking about artwork, we approached Gerry and we asked him if we could use one of his paintings and we were very grateful that he agreed.

PB: Martin is also a painter and an artist. Why did you go for Gerry's artwork rather than Martin’s?

DK: Martin was going to do the artwork originally, but when we were looking over it and talking about the idea of what we were doing he said, “I can’t do it any more justice than that. This really works and this really fits and if Gerry is up or doing it…” It was a real manifestation of the songs that we had written.

PB: It was very generous of Martin really.

DK: If you are doing anything either with songwriting or in a band, then you really should be generous and try to think of what the whole is rather than just your part in it. That is one thing about Martin. He doesn’t have an ego, which is not always typical of someone who is the front man or seen to be the main man in a band.

PB: It has been six years since ‘Dark Passenger’. Why has it taken so long for this album to come out?

DK: It was because we did everything ourselves. We mixed it, produced it, did the whole thing ourselves. It was also down to the fact that we were trying to think a little bit more about what we were doing rather than doing it in the way which we did before which was get a collection of like-minded songs together and whittle them down. We were very determined that this was going to be eight songs that fitted with what the narrative was and that took a bit longer. The next album won’t be like that. We are already quite well advanced with it and hope that it will be out towards the end of the year.

PB: Will that be a Filthy Tongues rather than an Isa & The Filthy Tongues album?

DK: Yes.

PB: What is the situation with Stacey Chavis? Has she permanently left the band now?

DK: No. When we started the Filthy Tongues, the initial stance was that it would be Martin that would do the singing, but then Stacey sung on a few songs and it snowballed into Isa &The Filthy Tongues from there.

We always had this ‘Jacob’s Ladder’ project niggling away in the background. When Stacey decided that she wanted to take a break for a while, we decided that we would go for that and also a follow-up as the Filthy Tongues and we would then see where we are. I think we will definitely, however, be doing some more albums with Stacey.

PB: What format is the follow-up going to take?

DK: We hope that it will be a similarly coherent set of songs. There is always an overspill to what you do. You never go into the studio and just record eight songs and those eight songs are the ones that go onto the album. You typically have a pool of songs that you are working upon and inevitably you let some of them fall by the wayside because they are not really fitting with what is going on at the time. Then you go back and hammer them up to see if some of those ideas are fitting in with where you are now. Then usually you find that there are things that you made ten years ago that suddenly fit in perfectly with what you are trying to do now. There is no particular theme to the next album at the moment, but that will come when it comes.

PB: Goodbye Mr Mackenzie were always defiant about staying in Edinburgh rather than moving down to London where the music industry is largely based. They did really well in Scotland, but never broke through down South and into the mainstream. Do you think that your refusal to shift down London was a big factor in that?

DK: It is hard to tell. You can think that if this had happened that might have happened. Personally I had a fantastic time with the Mackenzies. We did some great tours, great concerts, recorded in some brilliant places and made some fantastic friends. I don't have any regrets and there are no what ifs about it for me. It is what it was. We could have come down to London and they might have hated us.

The thing about the Mackenzies is that we didn’t easily fit anywhere. A record company is trying to make money first of all. Any company has to exploit their propositions, and that is why you often get a spurt of bands in a particular style. When one becomes a success, it is easy for a record company to say we will get another band like that because it is easy for them to package and to explain it to radio and press. We weren't doing anything that earth-shattering, but we didn’t fall into any of those groups. A lot of our lyrical content, for example, made it hard for the two major record companies that we were with to promote it. If you’re making life difficult like that, then it is in the lap of the gods whether that becomes a virtue or whether at some point they will turn around and say that they don’t know what to do with this. There was an element of that with the Mackenzies.

PB: Shirley Manson sung backing vocals and was the keyboardist for many years in Goodbye Mr Mackenzie before taking lead vocals on 'Nowhere Girl' on ‘Five’. How did you go from that to forming Angelfish?

DK: We had actually had plans that Shirley was going to sing on more of the next record, but then MCA, our record company, dropped us because of management issues. There was a lot of legal stuff going on and they weren’t really interested in us anymore.

MCA had a sub-label called Radioactive Records. The guy who ran Radioactive Records was a guy called Gary Kurfirst who managed the Ramones and Steely Dan and had signed the Mackenzies to Radioactive in America. After everything that happened with MCA, he kept an interest in the band and said, “I am not partaking in any of this legal bad feeling. I would like to keep working with you, but I can’t walk through the door and say that I have signed Goodbye Mr Mackenzie again.” As we had talked about Shirley doing more singing, he suggested forming a project with a different name in which Shirley sung and we wrote all the songs. So, we did the Angelfish album after which Shirley became involved with Garbage.

PB: Angelfish got back together last year for a one-off charity show in Glasgow. How did that come about?

DK: Shirley is friends with Morag Williamson, who runs the charity which is called the David Williamson Rwanda Foundation and provides fresh water and health care in Rwanda. Although Morag was one of Shirley’s friends, we knew her from Edinburgh from a long time ago. They had been talking about putting on a charity concert for a while possibly with just Shirley singing in it, but then Shirley emailed us and said, “Would you do this?” It was a good cause and it was nice to play those songs again.

PB: Is it true that the Glasgow gig was Angelfish's only ever British show?

DK: Yes (Laughs). The only other gigs that we had played in Europe were in Belgium and France and all the other gigs were in North America.

PB: Martin is dismissive of the final Goodbye Mr Mackenzie album, ‘The Glory Hole’. He has said that he had “lost the capacity to be intellectual” on it. Would you agree with his assessment of it?

DK:(Laughs) Any band’s back catalogue is going to have spikes and troughs in it. That is the nature of it unless you are some kind of weird genius or are an uber fan. I think there is some good stuff in there. It is what it is and for other people to take what they want from it. I wouldn’t want to hear Joe Strummer going on about how bad the production was on the first Clash album and how he would have done things different. I think that it is for other people to make up their mind about it. They are probably right, and it is not for me to persuade them one way or the other.

PB: Finally what plans do you have for the immediate future? Is playing dates going to be your main focus during the next few months?

DK: We are going to do what we can to promote ‘Jacob’s Ladder’. After being away for six years, it is going to take a while for people to hear or to catch onto it, so for next few months we are going to try to make people aware that the album is out there.

PB: Thank you.

Band Links:-

http://www.isaandthefilthytongues.com/

https://twitter.com/filthytongues

https://www.facebook.com/Isa-the-Filth

Picture Gallery:-