published: 5 /

2 /

2016

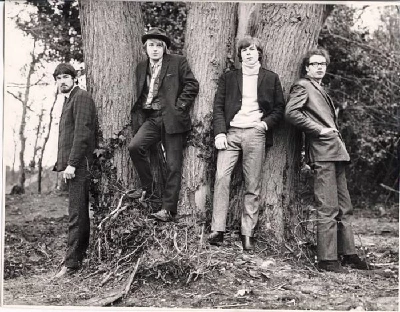

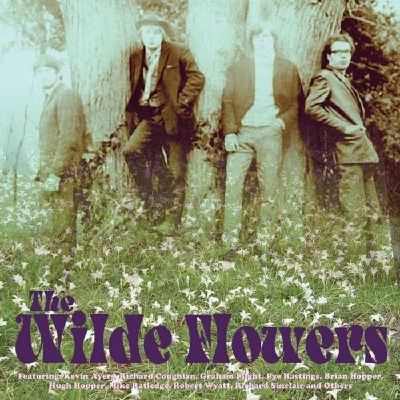

With the release of a collection of 1960s Canterbury Scene band the Wilde Flowers and associates, founder member Robert Wyatt reflects on those early years, his subsequent musical career, collaborations and political commitment

Article

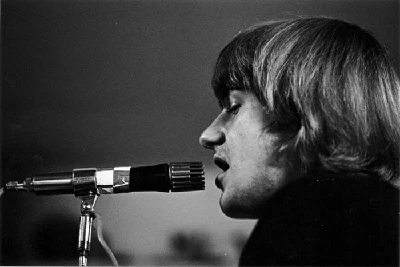

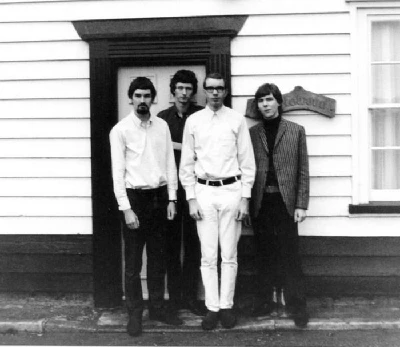

Robert Wyatt is one of those musical figures who, while never reaching great commercial heights (nor aspiring to), is nonetheless admired by many musicians and singers and has a small but devoted audience. Beginning with Canterbury band the Wilde Flowers, then later moving on to Soft Machine and Matching Mole, a traumatic accident in 1973 when he fell from a fourth floor window that left him paraplegic meant that he had to reappraise his musical future.

He had been a drummer as well as a singer, but in the years since then has become chiefly known for his voice and its peculiarly English soulfulness. A number of solo albums, starting with ‘Rock Bottom’ in 1974, have expanded his reputation, along with many collaborations along the way with such artists as Elvis Costello, Eno, Ultramarine and Bjork.

With the release of ‘The Wilde Flowers’, a compilation of the band’s work which also signifies his own earliest musical forays, it was timely for Pennyblackmusic to speak to Robert Wyatt about his history and his influences.

PB: What are your earliest musical memories?

RW: Just as a listener, it must be before my memory got into gear, but I must have heard music when I was born. I certainly feel great nostalgia for that period (the 1940s), presumably rooted in hearing the radio, and my family's records.

But as a participant, singing Christmas carols with my dad on piano and watching 'Let's Make an Opera' by Benjamin Britten, written for children, mostly, to sing together.

PB: I believe you first met people like Mike Ratledge and the Hopper brothers at school. Was music the foundation of that friendship?

RW: What friendship? Whatever there was initially was soon eroded by mutual discomfort. Among a couple of us, perhaps, cordial relations endured. For me the friendship with, for example, Brian Hopper remains constant.

PB: How soon did you move towards actually making music together?

RW: When they wanted a drummer, and I wanted someone to play with.

PB: As there was a “Canterbury Scene”, do you think there was also an identifiable ‘Canterbury Sound”? How would you characterise it?

RW: We knew a lot more than we could actually play.

PB: You have an unmistakeable voice, but presumably in the Wilde Flowers era you started out influenced by and imitating other singers. (a) Who were they?

(b) How conscious a decision was it to pursue your own singing voice?

RW: (a) Mostly women, as unlikely as that may seem. Dionne Warwick, Betty Carter, Annie Ross. But also Peter Pears ( e.g. 'The Bonny Earl O’Moray'), Smokey Robinson and Van Morrison.

(b) When I really got into singing my own songs. I don't like acting out a part. I sing like I talk, in the end.

PB: Why did you leave the Wilde Flowers?

RW: To join Daevid Allen and Kevin Ayers in London.

PB: Were the subsequent Soft Machine years more satisfying for you ?

RW: No. I always felt totally inadequate. Still do.

PB: Do you feel that one effect of your 1973 accident was to move your music and writing in unexpected directions?

RW: Well, it forced me to be a tad more self-reliant, musically. (A band was, practically, out of the question.) I also found my own voice. Am I saying that losing the use of my lower limbs was, in a way, a godsend ? Yes, I am.

PB: Over the years, you have often collaborated with other musicians (e.g. Working Week, Ultramarine, David Gilmour). What do you feel music gains from such collaborations?

RW: Oh, so many things. Music is a social art, a ‘get-together’, if you're lucky. But the pre-eminence of groups as adolescent bonding rituals has more to do with sociology than aural aesthetics. Even a classical music concert soloist like the amazing Valentina Lisitsa chooses the company of the composers whose music she plays.

For what I play, the choice of which fellow musicians to play with can be mind-expanding. And singing duets, for example, creates something neither singer could really do on their own.

PB: You’re now well-known for your political views, but although you were musically active in the 1960s and 1970s, a period of great political ferment, it seems that your commitment only came to the fore after then. Would you agree? If so, why was that?

RW: My childhood was blessed with the innovative social security measures introduced after World War 2. I became distressed by the way that these started to be dismantled during my youth. And dramatically thereafter.

PB: Can music have a direct political effect?

RW: I haven't seen any identifiable evidence. I don't think it works like that - music itself reaches something inside me deeper than words.

As for lyrics, again, I don't know. People sing hymns and anthems, but do they have any proven effect? Will God save the Queen? Why would he intervene in that way? He didn't even bother to save his own son! Lyrics don't have to be proscriptive in that way.

PB: Perhaps its function is more to offer encouragement, defiance, hope?

RW: Maybe, yes, come to think. You put that very well.

PB: Having said towards the end of last year that you have stopped making music, what future plans do you have?

RW: I don't plan. Plans are traps.

PB: Thank you very much.

Band Links:-

https://www.facebook.com/pages/Robert-

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Robert_W

Have a Listen:-

Picture Gallery:-