published: 25 /

8 /

2015

Scottish singer-songwriter Roy Moller speaks to John Clarkson about his recent album, 'My Week Beats Your Year', which written after Lou Reed's death tells of the Velvet Underground's inspiration and role in his life, and 'Imports', his autobiographical debut poetry collection

Article

"There is something hammering on my shoulder now which wasn't there before," says Roy Moller at one point in an interview with Pennyblackmusic. He is talking to us on the phone from his home in the picturesque small town of Dunbar, which is thirty miles down Scotland's East Coast from Edinburgh, about his increased focus on autobiography in both his songwriting and also his new career as a poet.

An adopted child, Moller was born in Edinburgh in 1963. After leaving Trinity Academy in 1981 at the age of seventeen, he moved to Glasgow later that year, a city that he admits that he never felt especially comfortable in, to study English at Strathclyde University and then to work. Moller would spend nearly thirty-two years in Glasgow, before finally relocating to Dunbar in April 2013.

Moller's musical career began to take off in the late 1990s with first Peel favourites Meth O.D. and then instrumental outfit the Wow Kafe. He has also since been a member of Scottish "supergroups" the Store Keys, which also featured Belle and Sebastian's Stevie Jackson with whom he has co-written songs, and most recently Jesus, Baby!, which is led by the Fire Engines' Davy Henderson and performs songs by poet Michael Pedersen.

Moller released his first solo album 'Speak When I'm Spoken To' on Book Club Records in 2007. He followed this with 'Playing Songs No One's Listening To', which was released on the Ottawa-based label The Beautiful Music in 2011, and 'The Singing's Getting Better' which was recorded with Sporting Hero and came out on the Mecca Holding Co. in 2012.

Last year Moller joined the roster of the Edinburgh-based label Stereogram Recordings (The Band of Holy Joy, James King and the Lone Wolves, The Cathode Ray, Milton Star, Lola in Slacks), which is owned by Cathode Ray front man Jeremy Thoms, and released two albums in quick succession.

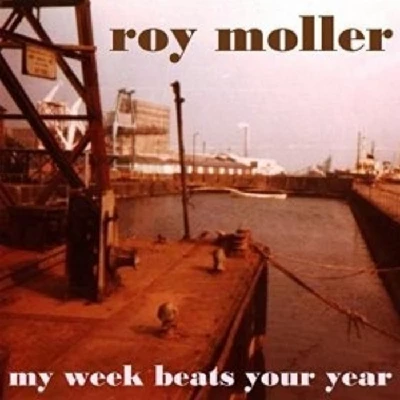

Roy Moller has described 'One Domino', the first of these, which came out in May 2014 as his "Edinbralectro record", and it name checks various Edinburgh locations. 'My Week Beats Your Year', which followed in July, and was released to coincide with a Edinburgh Festival Fringe show from Moller, is more autobiographical still. Written in a flurry of creativity after the death of Lou Reed the previous October, it tells of the teenage Moller's discovery of the Velvet Underground, his purchase of their albums in reverse order from long gone Edinburgh record shops, and attending the first two dates at the Edinburgh Playhouse of their infamous and ultimately ill-fated 1993 reunion tour.

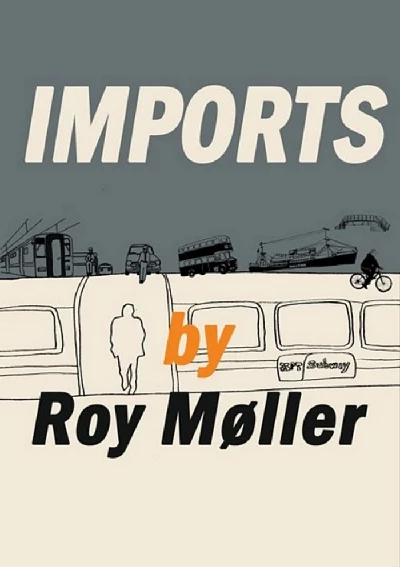

In what was a prolific few months, Moller also published his debut collection of poetry 'Imports' through local Dunbar-based publisher, Appletree Writers’ Press.

Pennyblackmusic spoke to Roy Moller about both 'My Week Beats Your Year' and 'Imports'.

PB: Your two recent albums, ‘One Domino’ and ‘My Week Beats Your Year’, are lyrically much more centred around Edinburgh than your first three albums. How much of that do you think has been inspired by your own move back after many years living in Glasgow to the East Coast of Scotland?

RM: A lot of that has certainly been down to that, although I actually recorded ‘One Domino’ prior to moving.

I played a Simon and Garfunkel tribute night at the Community Central Halls in Maryhill in Glasgow in 2011, and did a song called ‘Fakin’ It’, and decided to do it in the style of David Bowie with a cockney accent.

Afterwards this young chap came up and introduced himself as Michael Pedersen. Michael is an Edinburgh-based poet and is the co-founder of Neu! Reekie! which was starting in Edinburgh as an arts fusion club night. He started chatting to me, said that he had enjoyed what I did and invited me to do a turn at Neu! Reekie!

It was really a revelation because I had not been out in Edinburgh to any degree for years, and to see such an energetic and vibrant multimedia night as Neu! Reekie! really got me interested in what was happening in the East. It rekindled my semi-dormant East Coast identity, and got me thinking back to the way I felt about music back when I was in my teens. When I was writing the songs that became ‘One Domino’, I was physically in Glasgow but

I felt that my sensibilities were switching back East again.

When I moved through from Glasgow to Dunbar in 2013 lots of other memories of growing up on the East Coast came back and helped to inform the writing of both ‘My Week Beats Your Year’ and also the poems in ‘Imports’ as well.

PB: To talk about ‘Imports’, it is a poetry collection of four parts. ‘Cabotage’, the first part, is loosely about your early Edinburgh upbringing and your childhood memories. ‘Roll-on/Roll-off’, which follows it, is about travelling across over Scotland, ‘Without Reserve’, which comes next, about your Glasgow years and ‘Entering Inwards’, the final part, about Edinburgh and the East Coast again but this time told from the view of a late adolescent and adult. Did you set out from the outset to write something of four distinct movements or is that something which emerged when you started writing?

RM: I was conscious that I needed to apply some sort of structure to ‘Imports’. While I already had enough for a full collection, I wanted it to have a framework and an identity. So it really came from looking at what was already there, seeing what themes were emerging and then producing more work along those themes.

Maybe half the poems were written before I ordered them in that way, and then with the others I wrote poems that explored those four movements. I thought that by dividing the book into segments it would make the book easier to read as well rather than it just being a sort of sprawl.

I wanted ‘Imports’ to reflect my East Coast identity and being both a child and young man on the East Coast and then as an older man being back there. While Glasgow and Edinburgh are less than fifty miles apart, they are very different cities and living in them is like living in two different worlds. I really wanted to examine that as well because I hadn’t read much else that has really explored that subject.

PB: Many of those poems, especially in the last movement such as ‘Lessons’, which is about being bullied in school, and ‘Eighty Two’, which is about your adopted father’s sudden death when you were nineteen, could have only been written with the degree of distance that thirty years brings. Would you agree?

RM: I would absolutely agree. I wonder what other things will eventually emerge when I sit down to write them that have been at the back of my mind and completely dormant for decades (Laughs).

It is really strange to me that I feel closer to events that happened in 1982 now when I am sitting down to write them than I did five, ten years later. Poetry can dissolve time in that way as well. It is almost like the sense of smell. You can smell something that you haven’t smelt in years, and can be taken right back to the way that you felt at that time. It is like all the intervening years and all the intervening stages that you have gone through have just fallen away.

Having said that, though, to write a poem about being shoved into the pond at the Royal Botanic Gardens, or having my cagoule gobbed on and being bullied at secondary school in the late 70s, I wouldn’t have had the tools technically or the perspective to write about it back then. I probably needed the space of three and a half decades to really express that properly.

PB: You are now in your early 50s. When you get into late 40s or early 50s, you become conscious that time is running out, that if you are lucky you might have twenty-five good years left. How much of this shift in both your music and poetry to focusing on autobiography and this need to put things into perspective comes from that?

RM: I would say 100%. It actually lies behind the geographical shift as well. I wanted to move back beside the sea and the East Coast because I thought that as I got older I would feel more settled here in a way I had never done living in Glasgow.

I thought, “If I don’t write directly from it now, then what has my experience really been for?” I felt that I really needed to start setting things down, and that I was wasting time by doing some of the things that I had explored earlier in my songwriting, which were, to a degree, pastiches or exercises in a certain style. I felt that there wasn’t really time anymore to do a glam rock number just for the sake of doing a glam rock number, or a country number, now. There were reoccurring experiences in my life that I wanted to discuss, either in poetry or song, and I wanted to make some sort of record of it while I still could.

I think in poetry people often don’t really hit their stride until they are in their mid-40s. Norman MacCaig published two books of poetry when he was a younger man but he disowned them, and his first real book of poetry as far as he was concerned came out in his mid-40s.

PB: You wrote poetry as a young man, and when you were at Strathclyde University won the Keith Wright Poetry Competition, which is a major local writing award, yet for many years you abandoned poetry. Why did you stop? Was it because music took over?

RM: I didn`t feel that I had anything in common with local Glasgow poets. I have a memory of sitting in a pub with a guy reading his poem about losing his giro on Victoria Road, meeting a friend and getting drunk. I thought, “Just because I live here do I really have to talk about this stuff?” I was influenced by Ginsberg and the Beats at the time and I thought, “If I am writing poetry in Glasgow, people are going to want to hear stuff about living in Glasgow and I don’t really want to write about that,” so then I thought, “Whatever I do decide to write about, there probably won’t be an audience for it.”

Music seemed more universal to me, and it was something that I could create on the spot and not worry about what the potential audience was going to be, so that is why I really stopped writing poetry. I had no outlet for it at the time.

PB: There is a new documentary film ‘Big New Dream’ about the Edinburgh post-punk movement between 1977 and 1982 and bands like Josef K and the Fire Engines. It makes Edinburgh out to be a very grey, austere place in the 1970s. You make the point in ‘My Week Beats Your Year’ that much of the appeal of Lou Reed and New York to you was that it seemed much more exciting as well as decadent. Are those your memories of 70s Edinburgh too, as being bleak and dull and somewhat Calvinistic?

RM: I was, I suppose, a year or two young to experience Josef K and the Fire Engines live, or I should say to legally see Josef K (Laughs) as there were people who were my contemporaries who did. One of my classmates, Susan Buckley, married one of Josef K, Malcolm Ross, and she is on the inner sleeve of ‘The Only Fun in Town’. I missed out on that scene, though.

My memories of childhood and 70s Edinburgh are often of very sunny, happy days and of travelling on the bus for runs out to Ravelston Dykes and exotic places like that (Laughs). There is a contrast to that, however, which I was trying to invoke in ‘My Week Beats Your Year’.

Edinburgh has this Gothic side with its dark closes and Burke and Hare and hangings in the Grassmarket. I related that to the sound of the Velvet Underground. My awareness of the Velvet Underground and awareness of the history of Edinburgh more or less happened at the same time. They synchronised together in my head. I bought ‘The Velvet Underground and Nico’ from a record shop in the High Street called Phoenix. It was very much a cave within a small shop. It was surrounded by so much history, and it was just down the street from the Heart of Midlothian stone, where the old tolbooth was in Edinburgh and there again were all these hangings. There were all these different memories playing off against each other when I wrote ‘My Week Beats Your Year’.

PB: Edinburgh-based writers such as Robert Louis Stevenson James Hogg and more recently Ian Rankin and Irvine Welsh have also written for all its outward respectability of this undercurrent of darkness in Edinburgh. You were brought up near Trinity, which is very middle class, but it is literally a walk of a few minutes from Leith and its docks, which at that time in the late 70s when you first discovered the Velvet Underground was a pretty run down part of Edinburgh. Was that part of the appeal of Lou Reed then as well, that he was tapping into not just what was going on in Edinburgh but also your own local environment, just on larger scale?

RM: Yeah, absolutely. When I started at secondary school, the lower years - which were, literally, a riot - were based in an annexe in the heart of Leith, which was, as you say, both a few minutes’ walk and also a whole world away from Trinity.

From the bridge in Newhaven Road, near where I lived, you could see ships in the harbour from Leith Docks. When I first heard ‘Heroin’ and the line “I wish that I’d sail the darkened seas/On a great big clipper ship/Going from this land here to that/In a sailor’s suit and cap” it was so real to me. The old sailor’s missions and things like that were on my doorstep.

It all just started to fuse with me about the time I began listening to the Velvet Underground.

PB: Would you say then that ‘My Weeks Beats Your Year’ is as much about the synchronicity about 70s Edinburgh and 70s New York as it is about your own discovery of Lou Reed and the Velvet Underground?

RM: I tried to make it so. There are these other parallels as well, which I also tried to tap into on the album. Nico lived in St Stephen’s Street in Stockbridge for a while, and I have got a line in there about that. When Lou Reed reformed the Velvet Underground in 1993 he wanted to play the Edinburgh Playhouse because it was one of his favourite venues in the world, and I have lyrics about that and going to see the Velvet Underground at the two gigs they played there as the opening nights of the tour.

PB: You imply on ‘Electrify Me’ on 'My Week Beats Your Year' that it was a totally eureka moment when you first heard ‘Sweet Jane’ and the Velvet Underground for the first time after David Bowie played it on a radio show. Was it as instant and life-defining as that?

RM: It was. David Bowie was a guest DJ on a show on Radio 1 called ‘Star Special’. This was a series where people would come on and play DJ for two hours and thirty of their favourite discs. I have since found out that it was the 20th May 1979 (Laughs), and I taped the programme on my Boots cassette recorder. One of the songs he played was ‘Sweet Jane’, and I just kept coming back to it and back to it. It just blew me away, and it became my favourite record and still is.

PB: How quickly after that did you discover the Velvet Underground albums. Was it very quickly?

RM: It was quite quickly. It was amazing the number of people on ‘Star Special’ that played the Velvet Underground. Tim Curry was on a couple of weeks later and he played ‘Rock and Roll’, and then Frank Zappa was on and he played ‘All Tomorrow’s Parties’ which was again a sonic revelation for me that I couldn’t believe.

Within a month or two of hearing ‘Sweet Jane’ I bought Lou’s solo album, ‘Live; Take No Prisoners’. He does this Jewish stand-up comedy thing on it, which I love too. It was the only album that I could get that had ‘Sweet Jane’ on it, and it is a very different version, a kind of post ‘Street Hassle’ version.

A couple of months after that I was in Ezy Ryder record shop in Greyfriars Market in Forrest Road, and I was browsing through the bins and found ‘Loaded’ and bought that.

I got into the Velvets backwards and then the “The Banana Album” came about a year and a half later, which was another revelation. While they were an anti-psychedelic band in some ways, it was also the most psychedelic thing that I had ever heard. I remember my mind being blown by the toilet flushing of the last track on ‘European Son’ and thinking, “This is outrageous” (Laughs). When things make that much of an impression on you, they never leave you. When I put ‘Sweet Jane’ on now that almost African Hi-Life introduction takes me right back, and I still find it inspires in me the same sense of freedom music can bring.

PB: Why did you decide to release ‘My Weeks Beats Your Year’ out as a download in contrast to ‘One Domino’ which came out as well on CD?

RM: It was because of financial reasons, really. Both time and money prohibited us from putting it out on CD so soon after we had done ‘One Domino’. We made it a download for immediacy’s sake. If I could have my absolute wish I think it would be a nice thing to put it out on 10” vinyl. It’s very short. I did an Edinburgh Fringe show with Appletree Writers for ‘My Week Beats Your Year’, and we wanted the show to support the download and the download to support the show.

I wrote it and recorded ‘My Week Beats Your Year’ in a two-week period. It was Christmas 2013, Lou Reed had died in October of that year, and I had ten days in a row off work and knuckled down to it and wrote and recorded it at home. I have never had an experience like that before, and I probably will never have an experience like that again (Laughs). It dictated its own purpose, and it will always remain quite special to me in that sense because it came together so quickly.

PB: You have got another album in the pipeline with the Canadian label The Beautiful Music, who released your 2011 album ‘Playing Songs No One’s Listening To’.

RM: I sent Wally Salem, who runs The Beautiful Music, about thirty tracks a couple of years ago and he picked twelve of them for an album and that album is still to come out, so I made my selection for ‘One Domino’ out of the ones which I had left. They were all recorded at the same time. There will be an album coming out on The Beautiful Music eventually.

PB: Will that be your next album?

RM: Yeah, I think so. I am very happy to have people like Jeremy Thoms at Stereogram Recordings and Wally in my musical life. I have never really been in that position before where I have had people really pushing for the music, and they have both been great, as has Appletree’s Hannah Lavery.

A few weeks ago I was in Register House to have my adoption papers opened. I touch upon my adoption in ‘Mother Edinburgh’, the first poem in ‘Imports’ and I have found out that although I was born in Edinburgh, my actual mother came from Toronto and probably my birth father did as well. I hope that I can go over to Toronto soon to visit relations that I never knew I had. To have an Edinburgh outlet and a Canadian outlet seems very appropriate to my life at the moment.

PB: Finally, what other plans do you have for the future?

RM: I have enough things in my locker to create another album but Jeremy and I feel we are still to maximise the potential of ‘My Week Beats Your Year’, and that is our main priority at the moment. And there will be more poetry for Appletree Writers.

PB: Thank you.

Footnote: Shortly after this interview with Roy Moller took place in early June, he met his Canadian family for the first time. “I met my stepsister in London later on in June and then went over to Toronto in July to meet my stepbrother and their extended family,” he explains in an email. “I met four full cousins, one of whom, Chris Staig, leads a great band called the Marquee Players and plays guitar behind his head like T-Bone Walker. I also met one of my mother's sisters and spoke to her other sister on the phone. Having only really discovered my birth mother's full identity in May, to be doing this less than ten weeks later was an incredible experience for me. If my birth father was who we think he was I may have five Canadian half-sisters.”

Roy Moller will be playing songs from ‘My Week Beats Your Year’ and supporting Lola in Slacks at the CCA on Friday 28th August.

Band Links:-

https://www.facebook.com/RoyMoller1963

https://roymoller.bandcamp.com/

Have a Listen:-

Picture Gallery:-