published: 19 /

1 /

2024

Edinburgh-born singer and songwriter Roy Moller speaks to John Clarkson about his new album ‘Be My Baby’,which is about his discovery that his birth parents were Canadian and that his mother flew from Toronto to Edinburgh to give birth to and put him up for adoption.

Article

Scottish singer-songwriter and ex-poet Roy Moller had known since he was a child that he was adopted, but it was only later on in life in May 2015, and, at the age of 51, that he went to Register House in Edinburgh to have his adoption papers opened.

What he found out was both startling and life-changing. Carol Hoffman, his birth mother, had been a reporter on ‘The Toronto Telegram’. When she had accidentally fallen pregnant, knowing the stigma that she would face for this in the ultra-conservative 1960’s Canada, she had travelled to Edinburgh, where she had given birth to her baby, before handing him over for adoption and returning home.

After some more searching, Moller was able to confirm that he had been the product of an extra-marital affair and that his father was Jim Kennedy, a photographer on ‘The Toronto Telegram’ and a World War II war hero. Kennedy, who died in 2001, already had children, and Carol, who passed away in 2014, after returning to Toronto, eventually married and also had a family. Moller, who was brought up an only child in North Edinburgh, discovered that he has between his father and mother’s families six half siblings and a step-brother and sister, and has been over to Canada to meet them.

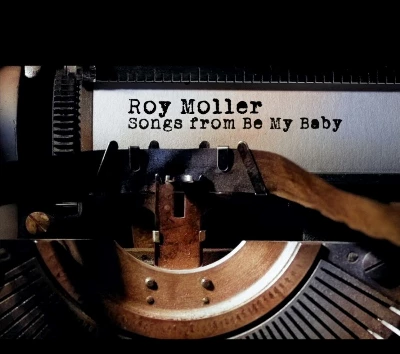

He first explored his discovery in his second collection of poetry ‘Be My Baby’, before leaving the genre. He has now released on the Ottawa-based label, The Beautiful Music, his seventh album – and first album in seven years - ‘Songs From Be My Baby’, which examines further the issue of his adoption. It tells of Carol and Jim’s meeting and brief affair, her flight to Edinburgh, and the young Roy’s upbringing in Edinburgh.

In what is his fifth interview with Pennyblackmusic, Roy Moller spoke to us about ‘Songs From Be My Baby’.

PB: ‘Songs from Be My Baby’ uses completely different lyrics to your poetry collection. ‘Be My Baby’. Did you want to write something that stood in its own right and which you wouldn’t need to have necessarily read ‘Be My Baby’?

RM: Yes, definitely. I think what works as a song can be quite different from what works as a poem. I was looking at my material and what I had already written and was wondering how maybe I could be a bit more emotionally direct, which I think the music accomplishes, often just with a chord change or a vocal. You can elevate something with music that expresses emotion. I am also certainly a more natural songwriter than a poet. I don’t think I am a really natural poet, not what is really understood as poetry anyway. I think with music I feel more comfortable.

PB: You started out as a poet back in the 1980s and turned to writing songs later. Why do you think that you are not a natural poet?

RM: I took my degree at Strathclyde University in Glasgow and when I went there I wrote poems. I just felt out of place. I was expected to be writing about cashing my giro on Pollockshaws Road and stuff like that, and I thought this is not me. ‘Imports’, my first book of poetry. came out in 2014 and ‘Be My Baby’ came out in 2019, and I felt like a fish out of water again on the poetry scene. It seemed like everyone expected me to think in a certain way and to be of a certain political viewpoint, and I started to ask myself why I was interested in making any sort of mark there. I didn’t feel any sort of freedom in writing poetry. I thought this is completely back to front, so I became completely disillusioned with the idea of putting myself up as any sort of poet. Circumstances were repeating themselves in the same sort of way as what originally put me off. I haven’t written anything now that you could call a poem since before the pandemic.

PB: Do you see yourself now as having permanently abandoned poetry?

RM: That seems like a grand thing to say. It sounds a little too authoritative, but I have abandoned poetry. Music is my muse. It is a little bit of an airy fairy thing to say, but in my heart I feel that. I think as well the pandemic has led to me connecting with music again, and the emotional sustenance that that provides for me. For some people poetry provides that, and that is great. I have read a few poems and a few books that have really connected with me,, but pound for pound what has always connected with me and always has done is music.

I used to find that writing poetry got me depressed, whereas when I am writing music I felt uplifted. So, I decided to move forwards with music and, although I called the album ‘Songs From Be My Baby’ to give it some sort of route in to what I had already written, I don’t want people to have read the book to get the songs. It just seemed the right title.

PB: You sing on 'Front West Street' about your birth mother that “Keep it hidden/An ocean away/You had a baby/Yes, you did/3,000 miles away” but most of your anger seems to be addressed not art all at your mum, but at the awful pressure that she was put under and at being forced to fly 3, 000 miles to give birth to you.

RM: There is no anger at any individual in this set of songs. I think it is not so much anger as indignation that she had to face that. I have to stress that it wasn’t family pressure. It was the morals of the time. Toronto was on the surface a very cosmopolitan city in 1963. If you look at the pictures of the time, it looks like a mini New York, and it was. For a male of a certain age, it required a certain kind of attitude, but if you were a woman that didn’t apply. My mother had just turned 28 when she fell pregnant, which is hardly a young girl, but being an unmarried mother then and there was such a big stigma.

There is no anger whatsoever towards my mother, my father or any family members because the way things turned out otherwise I would have almost certainly have not come to be. There is indignation, however, at the system at that time, and that a 28-year old unmarried woman had to go 3,000 miles away and keep a secret for the rest of her life.

PB: You were born in 1963. That was the year the world changed, and about which Philip Larkin famously said that “Sexual intercourse began between the end of the Chatterley ban and the Beatles’ first LP.” You must be conscious of the fact that if you were born two or three years later that this might not have happened and your mother might not have been forced to fly to Scotland.

RM: Yes, that’s right. She married another man when I would have been eight years old. ( don’t think that I would have necessarily fitted in that situation, so it was the best thing for me that I found an adopted family, who adopted me straightaway.

I have recorded a lot of other songs for the ‘Songs for Be My Baby’ project. I have got another fourteen songs, which I have held back, which are more reflections, and does recycle some of the poems from the ‘Be My Baby’ book, although again there are quite a few changes. There are more reflections in that series of songs about my adopted family and adopted parents.

PB: When do you hope to put that second record out?

RM: I don’t really have any plan as such. It is there in my Bandcamp waiting to go active for when the time seems right. It depends on how things go with the main album and The Beautiful Music label. We may release the tracks as bonuses and include them with the download or something, but ultimately I would like to have the whole thing released as a series of downloads in a certain order. Ultimately I would like to take all the songs and make an immersive experience out of the story. I have got a little more to unpack than what you necessarily hear.

PB: You sing on the last line on the album “Take some time to mend”. Do you see the ultimate aim for ‘Be My Baby’ and ‘Songs for Be My Baby’ as providing something cathartic, not just for you, but for your family in Toronto?

RM: Yes, absolutely. I recorded hat particular song, ‘Unravelling’, on the morning after Charlie Watts passed away, and I was feeling sad and I was feeling affected because I really like the Rolling Stones. In unfortunate circumstances I was in the mood to really do something quite rueful and I think that line “time to mend” came from the way I was feeling about Charlie Watts, but, of course, that opened up all the feelings I had underlying about the whole situation.

PB: How much knowledge did your family in Canada have that there was this child who had been born abroad?

RM: On my father’s side none whatsoever. On my mother’s side they knew that my mother had just disappeared for a long period of time, and that was in character for her, but they didn’t know the reason. I had a conversation with my stepsister and she was born ten weeks before I was born, so my stepfather’s daughter is a very similar age to me. One night when she was about twelve I gather that my mother sort of confessed that she had had a son about the same age as my stepsister, and my stepfather gleaned something and he would mention it when he was drunk, so it was there in the shadows.

PB: How much have you seen of your family in Canada? You first went over there in 2015 shortly after you found out who your mother was.

RM: I went over then with my wife and son, and met one of my mother’s sisters, and spoke to her beforehand on the phone and I met cousins, my stepsister and my stepmother. I had met my stepsister briefly before in London three months earlier, and I have been back a couple of times since. I have not been back since Covid, and in 2018/2019 and I met a lot of people on my father’s side then as well including my half brothers, one of whom was from a different mother than my other half brothers and sisters.

I have been very fortunate in the way that I have been generally accepted by both sides and, although I was born so far away, we have certainly found things in common. Not everyone has that experience. I am one f the fortunate adoptees in that regard. For some people it doesn’t work like that at all. I am very, very thankful for the way that these things have worked out.

PB: You have got two labels, Stereogram Recordings in Edinburgh and The Beautiful Music in Ottawa. Why did you decide to release this record on The Beautiful Music?

RM: Purely because of the Canadian connection. Ottawa is not all that far from Toronto. It just felt odd doing something with a Canadian theme and not doing it with The Beautiful Music. It was simple as that.

PB: How did you record this album ?.

RM: I recorded it in my spare room.. I used a program called Band in a Box which has virtual instruments. That is where I get the drum and the bass from. I played around with them so that they are nothing like the automated files, and then recorded guitar and keyboards and vocals here, and sent the Wav files to Stevie Walker, who co-produced the album and who is based in Switzerland,. We sent the files back and forth and we created the arrangement that way.

It took a long time. I started recording the album when I was 56 and I am 60 now. It has been quite a lengthy project, but I like it the best out of anything that I have done. I think that it has got more space in the arrangements, and the vocals are the most intimate that I have done and obviously the lyrics i connect with personally, It is a calling card of who I really am and I might not have shown it for sixty years of my life, but if you want to know where I came from and how I came to be me and how I act this is why. This is something that will always inform my work while I am writing songs and still performing them. It is a record that I am really proud of.

PB: Thank you.

Band Links:-

https://www.facebook.com/RoyMoller1963

https://roymoller.bandcamp.com/

Play in YouTube:-

Have a Listen:-

Picture Gallery:-