published: 14 /

11 /

2014

John Clarkson talks to Robert 'Hacker' Jessett from South London-based urban country outfit Morton Valence about their lyrical and experimental third album, 'Left'

Article

Morton Valence are a self-defined “urban country” outfit. Their music has many of the same ingredients as traditional country– its melancholy, much of its instrumentation and a similar focus on storytelling and narrative – but their songs, however, are set in their own native South London rather than America.

The band was formed in the middle of the last decade under their original moniker of Florida by Robert “Hacker” Jessett (vocals, guitars, trumpet and harmonica), who was previously a member of the Band of Holy Joy, and Anne Gilpin (vocals, keyboards), whose background is in contemporary dance. There have been various line-ups over the years, but the group now also consists of Joe Udwin (bass), who is also in the Crimea; Darryl Holley (drums) and Alan Cook (pedal steel guitar).

After a brief, unhappy tenure with a short-lived indie label which resulted in a solitary 7” single ‘Sailors’, Morton Valence, wanting to make music on their own terms, decided to form their own label, Bastard Recordings. Their 2009 debut album, ‘Bob and Veronica Ride Again’, which was released with the aid of crowd-funding, told of the stumbling romance between London slacker Bob and runaway Veronica, and was accompanied by a 110 page novella which was written by Jessett. Their second album, ‘Me and Home James’, came out in 2011, and tells of a late night/early morning journey in an illegal mini cab from South to North London and some of the characters the cab and its occupants pass on the way.

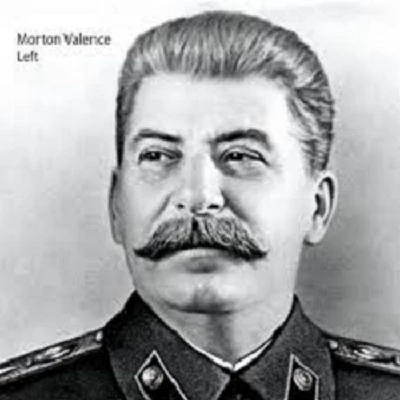

Morton Valence have spent the last three years recording abundantly both at home and also in the studio, and will be releasing two albums over the next few months. The first of these, ‘Left’, which comes with a stark black and white mug shot of a glaring Josef Stalin on its sleeve, was released in August, and is the more experimental of the two offerings. The second, which is provisionally entitled ‘Another Country’, will follow it, and is a more traditional collection of country ballads and songs.

‘Left‘, which runs to fourteen tracks, is extraordinary. An array of imaginative ideas, it opens in a cacophony of orchestration and with the nearly eight minute ‘The Day I Went to Bed for Ten Years’. Evaporating down to become a stark, acoustic folk number before building up again by adding rising layers of menacing distortion, Jessett’s hapless narrator tells on it of his fall from grace as he moves from snorting cocaine with a vacuous but hip in-crowd to hanging out with the winos in Vauxhall Park.

‘Old Punks’, which follows a few tracks later, is in two parts. In the first part, which is backed by a bossa nova beat, a weary middle-aged commuter, bored by his 9-to-5 routine and his dull life in suburbia, hankers for his youth as an angry-at-the-world punk. The less-than-a-minute, hilarious second part then recounts those glory years with a barrage of swearing and abrasive noise.

‘Annie McFall’ is the most harrowing track on ‘Left’. It features the wistful-voiced Anne Gilpin on lead vocals, who, backed by deceptively tender rolls of acoustic guitar from Jessett, takes on the mantle of the title character. “I never knew it was so easy to simply just disappear/I suppose it happens all the time,” she sings as an opening line. As the song progresses, it, however, becomes gradually clear that the sweet-natured, but unworldly wise and vulnerable Annie –who has always made the mistake of believing that “there is good in everyone” - is speaking from beyond the grave and has been murdered by her violent boyfriend.

‘The Return of Lola’ is an update of the Kinks classic ‘Lola’, and set some years after the original has its transvestite main character returning from a night out in her regular haunt of Soho to her home in the suburbs of South London.

‘Boyfriend on Remand’ was co-written by Jessett with Johny Brown, his former band mate and the frontman with the Band of Holy Joy. Its breezy tune intensifies the horror of the lyric, in which its drugs-hungry, out-of-control protagonist robs a petrol station and is involved in the assault of a security officer, but shrugs off both as being simply extreme examples of “enterprise culture”.

‘In Germany Before the War’ is a cover of a Randy Newman song, and, sung by Anne Gilpin, is another murder balled, but this time is told from the perspective of the murderer.

Pennyblackmusic have been fans of Morton Valence for some years now. We have presented them twice at our London Bands’ Nights. In the first show at the Half Moon in Herne Hill in late 2011, they appeared as a five-piece and played a storming, exuberant set. For the second show, which was our 15th anniversary gig and took place in May of this year at the Lexington in Islington, Jessett and Gilpin, as some of the other members of Morton Valence were abroad, elected to play as a two-piece. With Hacker sitting on a bar stool playing acoustic guitar and Gilpin standing beside him, this set could not have been much more different to the first one, but was equally visual and gripping, the pair pulling the audience in with their hushed vocals and taut lyricism.

We met up with Robert Jessett a few weeks after that show. In what is our second interview with Morton Valence, we spoke to him about ‘Left’.

PB: ‘Left’ is a much darker album in comparison to your other records, isn’t it?

RJ: Yes. It moves much more to the left, and so that is partially why we gave it that name. It is also much more experimental. Anne and I in particular are both into Krautrock. We also listen to a lot of stuff like minimalist Eno and those are both elements that you can hear on ‘Left.

PB: When do you hope to release ‘Another Country’?

RJ: ‘Another Country’ should come out later this year or in early 2015. We want to release ‘Left’ and ‘Another Country’ in fairly close succession. We are also now currently working on a fifth album which we plan to record live, and we also hope to put out a live album at some point.

PB: Will all those come like ‘Left’ and your previous albums on Bastard Recordings?

RJ: I think so, unless of course someone wants to give us a million dollars (Laughs). We have been offered loads of small indie deals in the past and no money, but to be honest there is not much a small indie can do that we can’t do ourselves and so we are better self-releasing it.

PB: Did you find it hard deciding what was going on ‘Left’ and what was going on ‘Another Country'?

RJ: Not really. It almost chose itself in a way. The tracks almost by default ended up on either one or the other. We booked ourselves a lot of studio time with ‘Another Country’. We then locked the door and we recorded it in the old-fashioned traditional way you would record an album, whereas ‘Left’ was much an album that we recorded at home or experimenting with friends. It is more all over the place (Laughs).

PB: Do you have your own home studio?

RJ: Yes. My living room becomes a studio, and I drive my neighbours nuts (Laughs).

PB: How many of the songs on ‘Left’ go back a long way?

RJ: Some of the recordings are older recordings. They have been around a while, and some of those older recordings were scheduled to go on other albums in the past and we didn’t actually use them, not because they were sub-standard or outtakes or anything like that, but simply because they didn’t fit into the plot and structure of either of the two previous albums.

The oldest song is probably fifteen or twenty years old, but they were all recorded more recently than that. The oldest recording goes back to 2009 when we were doing ‘Bob and Veronica Ride Again’, but some of our most recent recordings are on there as well.

PB: Why have you decided to release two albums in quick succession, rather than one double album?

RJ: It is because we haven’t put anything out since 2011. We have, however, never stopped working and writing and recording. As such a substantial amount of time had gone past, we suddenly had a load of songs. We had a double album worth of songs, but because they were to me in very different styles I thought it better to put them out as two albums rather than as a gatefold Roger Dean mega double album or whatever. I liked the idea of two separate albums. I don’t really like albums that are that long.

PB: Why did you decide to put a picture of Stalin on the sleeve of ‘Left’?

RJ: Well, it is certainly not because we are Stalinists. I liked the image because I think that it reflects the music on the album, which is cold and unnerving. I like the idea as well of fetishing dark characters and putting them in a different context, and that is what we have done with this. It has really got a reaction out of people, sometimes positively and sometimes negatively, but anybody who thinks we are Stalinists is missing the point completely. If people were to take it literally, I would find it very strange and disturbing. It is like that artist that did that picture of Myra Hindley. Obviously he was not condoning Myra Hindley. He was putting out a bold image that people would definitely respond to one way or the other and, okay, Stalin isn’t Myra Hindley, but it usually gets a reaction and I like that.

PB: ‘The Day That I Went to Bed for Ten Years’ describes a character that goes down a path of complete self-destruction. What inspired that?

RJ: Probably that track is the nearest that I have ever got to writing an autobiography, even though like most autobiographies I have embellished the truth with a lot of exaggeration. It is a story of the character who at the beginning has a lot of dreams and ambitions, and who gets sucked into a world that he thinks is really cool and that is going to make his dreams come true. Then he realises that it is not and that he is being lured into a world that is basically going to destroy him and – here is where I deviate from what happened to me - he ends up on the streets more or less a bum. He nearly dies. He wakes up in a hospital bed and a beautiful nurse saves his life, and they get married and have kids and live happily ever after.

PB: There is a line towards the end of the song – “Things have gone a little mainstream to me” - which implies that he could end up self-imploding again.

RJ: Yeah, sure. Maybe the ending is a bit like the end of ‘A Clockwork Orange’. He is like, “Boy, I am cured,” but I think that when you are a person of that kind of spirit it is inside you forever. You have to learn how not just to treat and deal with it but also to live with it.

In the first scene he is with the hipsters and fashionable media set and he is taking cocaine with them, but then he ends up in a park and drinking super strength alcohol with a group of bums, but he realises that both parties are pretty much cut from the same cloth. He realises that they are all the same, and the only thing that really saves him is that when he buys into a life of 2.2 children and domesticity with a suburban house. It is, however, open-ended like all great books are open-ended. I am not, of course, saying that this is a great song necessarily.

PB: ‘Old Punks’ captures the lives of so many people that have been aligned with a movement or particular genre of music when they are younger, whether they have been punks or hippies or rockers or something else. When they are seventeen or eighteen, they think that they are never going to change or be anything else, but by the time that they are thirty-five or so they have settled into a comfortable middle-class existence in suburbia.

RJ: The main character in that is the classic old punk. I put a bossa nova back beat to that song and got a lot of my inspiration for that from that Nouvelle Vague album (‘Nouvelle Vague’, 2004 -Ed), which set songs by lots of punk bands to bossa nova rhythms . ‘Old Punks’ is an original song and not a cover version, but I found the idea of punks in their fifties with a pipe and a pair of slippers and their feet up and listening to ‘Too Drunk to Fuck’ with a bossa nova beat quite interesting.

There is, however, a kind of a twist in the end with the ‘Part 2’ version.

You have ‘Old Punks Part 1’ and then it has a footnote which is ‘Old Punks Part 2’, which is the character going back to his roots.

PB: The most disturbing song on the album is ‘Annie McFall’, which is sung by Anne from the viewpoint of a murder victim.

RJ: It is definitely the darkest track on the album. It is about somebody whom people many possibly might regard as being from the underclass, and that is why when they disappear nobody misses them. It could almost be good riddance from society’s point of view. Annie McFall is someone that has basically grown up with no family and no love, and she suddenly finds love with somebody, and the person that she has found love with ends up murdering her. The whole reason that she ended up with this particular character is that she made him feel something that she had never felt before and which most people have felt from their family.

I think that Anne really gives the song a beauty. I have no idea where that track comes from, but it is my favourite song on the album.

PB: ‘The Return of Lola’ is in an update of the old Kinks song. How did that song come together?

RJ: I started out writing songs by changing the lyrics to songs that I liked when I at a very young age. The first song that I ever wrote was a rewrite of Bobby Goldsboro’s ‘Me and the Elephant’, but I got the line wrong and made a classic misinterpretation of the lyric. Bobby Goldberg talks about going down to the zoo to “kill an hour or two”, but I always thought that he was going down to the zoo “to kill an owl or two,” so I did a rewrite about his girlfriend and him going down to zoo and massacring all of the animals (Laughs). I think probably lots of people start like that.

‘The Return of Lola’ is a blatant rip-off of ‘Lola’. I don’t make any bones about it, hence the title. People have always done that. If you look at a song like ‘My Sweet Lord’ by George Harrison, it is just a rewrite of ‘He is So Fine’. ‘The Return of Lola’ is basically a rewrite of ‘Lola’. It is an update of where Lola is now. In our version she is coming back from a night out in Soho and returning to Morden, which is where I also was brought up.

PB: You wrote ‘Boyfriend from Remand’ with Johny Brown from the Band of Holy Joy. You were a member of the Band of Holy Joy at one point, weren’t you?

RJ: I was in Holy Joy in the early 1990s, just after they recorded ‘Tracksuit Vendetta’. I did some touring with them, and I collaborated with Johny quite a lot when Holy Joy after that went into hiatus. We wrote a whole bunch of songs together.

PB: What has happened to those songs?

RH: Most of those songs have fallen through the net. There was a song called ‘Someone Shares My Dream’, which we wrote together that is on one of the Holy Joy albums. I always liked ‘Boyfriend on Remand’ a lot. It has got a very strong lyric. I like the juxtaposition of it.

PB: The main character is horrifying. She has no morals or ethics, yet at the same time in her own mind she is able to justify completely everything she does.

RJ: Yeah, exactly - “This enterprise culture, you begin to understand.” She is horrible, but at the same time she is certainly no worse than certain members of our establishment who make nasty money in even nastier ways than she does.

Most of the lyrics for that one are Johny’s. I think that Johny is one of the best lyricists in the last thirty years. He is someone that inspired me a lot. I met him a long time ago now. He has got a fantastic vision and he is totally uncompromising. He could have gone in many different directions, but he has remained true to what he believes in. I think because of that that is why Holy Joy have survived until this day. The Band of Holy Joy could have easily lived on their past glories, but they don’t. He is always creating new stuff. He is a genuine one-off. I have never met anyone like Johny.

You meet a lot of people in the music business. They tick the right rock and roll boxes, but they are often doing a caricature of what they should be doing. If you read most people’s lyrics without listening to their music it is not particularly inspiring, but you can pick out a Holy Joy record, take out the inner sleeve, read the lyrics and it is poetry. It is something

which I try to aspire to with Morton Valence’s music.

PB: ‘In Germany Before the War’ is a cover of a Randy Newman song. Musically it is very sweet, but it about a murderer. Why did you want to cover it?

RJ: It is a response to ‘Annie McFall’. Anne sings on both of them. I like the fact that on ‘Annie McFall’ she is the victim, and ‘In Germany before the War’ she is the murderer. It is the first ever proper cover version that we have ever done. It was Anne’s idea. She had listened to ‘Little Criminals’, the album on which it appears upon, and I didn’t know either that album or that song beforehand at all, but she was really keen to sing it.

It literally it took us about half an hour to record. There is not a lot of instrumentation there, and I met her one afternoon and literally we sat there, played it and cut it, and then we sat there and listened back to it, and immediately I thought that it was one of the best things that we had ever done and I would still hold by that. I think Anne’s vocal on it amazing, again totally understated.

It is, like a lot of the tracks on this album, a really dark, grisly song. A lot of people will say that is really depressing, but I think, okay, you’re paying money to see a film with very dark subject matter or you will go and see a Shakespeare play. You will go and watch ‘Othello’ or ‘Hamlet’, and it is all very grisly and nasty with lots of back stabbing and very violent. When you go and do that in music, however, people criticise you for it, but to me it is just drama. To me, there is nothing depressing about great drama. The only thing I find about depressing music is bad music and so called “uplifting” kind of happy music. It is extraordinarily depressing because half the time it is really bad. I guess our music is an antidote to what is going on in the mainstream. We are not celebrating misery at all. It is just a different perspective on life, and to quote the Carter Family it is a “picture of life’s other side.”

PB: Thank you.

The photographs that accompany this article of Morton Valence were taken at Pennyblackmusic's 15th Anniversary Gig at the Lexington in London on the 31st May by Dave Goodwin.

Band Links:-

http://www.mortonvalence.com

https://www.facebook.com/mortonvalence

https://twitter.com/mortonvalence

Have a Listen:-

Picture Gallery:-