published: 14 /

11 /

2014

In this archive interview Eric Clapton talks to Nick Dent-Robinson about his autobiography and long musical career

Article

Eric Clapton is much more than a rock star. Like Dylan and McCartney he is an icon, a living legend. His solo career has spanned over three decades so far; he has sold more than 40 million records; played sell-out concerts worldwide and has been key to many major musical developments of his time. Tracks such as ‘Layla’, ‘Wonderful Tonight’, ‘Tears in Heaven’ and ‘Sunshine of Your Love’ are anthems for generations of fans. His guitar-playing has even seen him hailed by some as “God”.

Eric Clapton's journey to stupendous success has, however, had its darker side. Born illegitimate in 1945, the young Eric was raised in a Surrey village by his grandparents, believing for his first nine years that his “missing” mother was his older sister. He felt a misfit throughout a troubled childhood and young adolescence; his only solace was the guitar. But gradually Eric's obsession with the instrument led to him becoming a cult hero around the London and South East club circuit. And, after commercial success in the , Eric formed the first ever “super group”, Cream.

By 1966 he was a world superstar. Then came Blind Faith and Derek and the Dominos followed by decades of dominance as one of the finest guitarists this planet has ever seen. But in parallel were near-fatal addictions to drugs and alcohol; the tragic death of his four-year-old son, Conor; the loss of numerous close friends like Jimi Hendrix, Stevie Ray Vaughan and John Lennon; the break-up of his first, childless marriage and the failure to sustain relationships with scores of beautiful women. Even as he scaled the highest pinnacles of worldly success, Eric's demons never deserted him.

Yet, above all, Eric Clapton is a survivor. And he has always found a way to cope. Now happily married to Melia, an American who is half his age, Eric still lives close to where he was raised in Surrey. The couple's three daughters and a fourth daughter by a previous relationship are at the centre of his world. Finally, Eric is more at ease with himself. So much so that in 2007 at the age of 62 he felt able to write his “definitive” autobiography.

Eric Clapton talked to Nick Dent-Robinson about the experience of writing his searingly honest account. He reflected on some of the more memorable milestones along the road of his remarkable career and life and looked to the future too.

Mr Clapton greeted me rather formally. Firm handshake, thin smile, bespectacled eyes. Courteous, businesslike but a little distant. Not unlike meeting a mortgage manager at the local bank. But quickly the atmosphere warmed a little. Within moments first names were being used. We talked about the weather, Ferraris and classic Jaguars, Los Angeles, our meeting years before in his Blind Faith days and Oxfordshire villages and pubs he'd enjoyed back then. The familiar face was now smiling slightly, the manner almost avuncular. Time to ask some questions.

NDR: So, why did you finally do the “definitive” biography? Did you feel a sudden need to write it? Was it hard?

EC: People kept asking me. You know, reformed addict, past alcoholic...they said I could inspire others and so forth. That's nice if it happens but it wasn't the point really. I'd always kept diaries and had always meant to tell the life story properly one day. There'd been other books for various commercial reasons. But this one wasn't done primarily to earn money. Yes, I know the advance for the US rights was big but for me finance was definitely not the driver. I just wanted to get the proper story on the record.

In fact I think more people should write about their life, not just those who are well known. Many ordinary folk have wonderful stories. Anyway, I suddenly found I had the time. And it was therapeutic doing it, though hard. Unbelievably upsetting at times. Reliving some of the childhood insecurities was maybe necessary for me but not fun. And focusing to try to make more sense of the blur of the drug and alcohol days was a nightmare. Plus the mess I'd made of so many relationships and the pain I'd caused others. Not good. And I hadn't always taken the time to grieve loved ones who'd passed on. The book gave me a chance to reflect and do that. Traumatic but necessary. Though it was great to relive some of the musical bits. Thinking about musicians I'd known and music I'd heard or helped create, that did make it all worthwhile. And the story has ended up unbelievably positive really. A real-life Hollywood ending. Some days I wake up and can't believe my luck now and how life came good for me – finally. Makes it easier to accept there is a god.

NDR: The book is fascinating. It's not an easy read though. Not comfortable.

EC: Right. But it wasn't an easy or comfortable life. It was hell at times and I don't shirk from that. It's no bad thing for people to know about the discomforts, the nightmares others suffer. Especially so-called celebrities. This celebrity thing has got out of hand. Not just for me but generally. I have always loathed it. Even before I was one, when I was on the outside looking in. I never lusted after it. Never. But it's part of commercial success and I have to accept that.

To me the music is what matters. My worst nightmare would be to wake up one day and find I was a rock musician who is a huge celebrity but not known for his music. For me that would be hell, intolerable. In as far as I am known at all I just want it to be for the music I make. It is music that has helped me through all the troubles of my life and that's what I feel committed to.

NDR: In fact, right from childhood, the guitar has been your solace, your saviour, hasn't it? But it was surprising you never saw yourself as a natural guitarist; playing guitar was something you needed to work really hard at.

EC: Exactly. Solace and saviour was just what the guitar was for me. I worshipped the instrument. Still do. But I had to really slog to learn to play it. I'm still learning. The aspiration was always to be the world's greatest guitarist but, despite the hype, I never felt I achieved that. All that “Clapton is god” thing just came from a young photographer taking a picture of some graffiti which said that on Islington tube station. The star of that photo was actually a dog peeing and there was supposed to be an irony there...you know, the dog showing how little it thought of the slogan. But, as so often happens, the irony was lost along the way!

There aren't many “natural” guitar players; just a very few. I am not one. I just toiled and toiled in my obsessive, determined way and, after ten years or more of grafting, I'd started to master the craft.

I believe in graft. In single-minded commitment. That belief in a work ethic goes back a long way. In my late teens I was shocked to be dropped from art school – for focusing too narrowly and intensely on just one or two projects and not following the official programme – and I then had to work as an assistant for my grandfather on a building site, extending a school in Cobham, Surrey. I still look at the brick walls I helped build when I drive by that school.

My grandfather was a fine master bricklayer and worked solidly to a rhythm all day, producing more quality work than anyone. In those days there were many on building sites who just shirked, looked busy but took delight in doing as little as possible. My grandfather despised them. I became like him. I worked like fury – on the buildings then but later just the same in music where there are also many shirkers to be found! And computers that help compose or arrange tunes, or enhance voices or adjust out of tune singing or playing to make it in tune, or correct rhythms to the proper beat, all of that has made some younger musicians very lazy. They are not in the same game I am in. As far as I'm concerned, they make a mockery of the music business.

NDR: Tell me about some of the musicians you respected in the early days. Who inspired you?

EC: That's a pleasure. There were a few. Some are not widely known as my interest was always blues-based and blues players are often not household names. Top of the list has to be Robert Johnson. Quite simply the finest blues musician that ever lived. And the deeper I've immersed myself into the blues, the more I've realised there's nobody as soulful as Johnson. I just connected with him from the moment I first heard him. A huge inspiration. Then there is J.J. Cale and Muddy Waters with Little Walter and B. B. King and Ray Charles and Buddy Guy. The list goes on.

I recall my early exposure to trying to play genuine, quality blues. In the early days of the Yardbirds when the band was totally blues-orientated we toured England with American blues harmonica player Sonny Boy Williamson. In those days the UK musicians' union would not permit foreign supporting players to accompany visiting major stars. Which meant British musicians had the rare chance to gain direct experience working with the big names who toured here. Williamson was not an easy man but I was in awe of him. We had so much to learn though, and I was gutted when I heard Williamson saying to all who would listen, “These English kids, they want to play the blues so bad and you know they do play the blues so bad.” What hurt was that I knew he was right. We were novices. It made me doubly determined to work and work until I had learned to play better.

In a different way I do also have respect for some of my own contemporaries. For example, Albert Lee is greatly underrated as a guitarist and Jimi Hendrix was amazing. Plus I had admiration for others in a rather different mould to me. For example, Lonnie Donegan's contribution in the UK was important along with that of Hank Marvin who introduced many people in the UK to the guitar. And Joe Brown is good too - not least for the sheer range of his guitar skills and his ability on so many other instruments. I admired Bob Marley as well as Robbie Robertson of The Band and Bob Dylan. Though I was a late convert to Dylan; I only really began to get him when he went electric with ‘Blonde on Blonde’. And, though he'd be amused to hear me say so, George Harrison was also a far more original and skilful guitarist than is widely acknowledged and pretty useful on the sitar and the ukulele. Not many people know about that. George's talent as a songwriter has also been sadly underrated.

NDR: You were pretty negative about the Beatles back in the 60s, weren't you? Was it their commercial success you had a problem with?

EC: It was, yes. But not because I envied them. I always liked them individually as people, especially George and John. I knew them from 1963 when I was in the Yardbirds, and we were in some dreadful Christmas entertainment show together at the London Palladium and then at the Hammersmith Odeon. I was going through a bit of a pseudo-intellectual stage then and reading American underground writers like Ginsberg and Kerouac and watching Japanese and French films. I took myself far too seriously. I was against big commercial success! And I saw close up what the Beatles had to go through when Beatlemania was at its height. I noted how they had to wear their stage outfits even when they were off duty at clubs in the evening, how they were expected to shake their mop top heads in unison for the cameras and always be grinning and cute.

Worse than that, I saw how half the country copied them. I found it sad. The music was overwhelmed by the nonsense. All that loss of identity. It did George damage for years after. So, I was negative about the Beatle industry and a big reason for that was I really liked the very bright guys who were the Beatles and I rather pitied them.

Does that make more sense now? Certainly I liked their later work a lot. And one of my proudest moments was being invited by George to play with the Beatles on their ‘My Guitar Gently Weeps’ track in later years.

NDR: Were you always gloomy and curmudgeonly, even in your young days?

EC: Particularly in my younger days. I had the most negative attitude of anyone I knew. But I still always think the worst initially. About anything, really. Situations, people. Especially people.

NDR: And about women in particular?

EC: Not now. But for years I did. Often I saw the very worst in them. Or else I saw them as untouchable goddesses to be fawned over in the hope they'd idolise me. And when they did, I no longer wanted them. I would instantly despise them. I am still a bit like that with possessions. I'll long for a particular car or boat or painting or expensive watch. And often, once I have it, I no longer want it. Within the hour, my whole feeling changes.

A cliché no doubt, but probably this all goes back to the sense of abandonment by my mother when I was a child. Never knew her, found the person I knew as my sister was actually her, then she promptly ups and leaves me to start a family in a far-away land with a new husband. She totally abandons me. It wasn't well handled, either. So, that might be a reason for a lot of my early insecurity, though not an excuse for some of my problems with relationships. I think I was just always wanting things or people as a substitute for that maternal love I missed out on. And then I abandoned those things or people when I found they weren't satisfactory as substitutes. When they didn't ease the inner pain. This was all happening at the subconscious level, of course. None of it was done knowingly or with any insight into my own psyche, not at the time anyway.

NDR: Rock bands in the 60s and 70s didn't always treat female fans too well, did they?

EC: Unless you've experienced it personally, the full force of frustrated female fantasy can be a frighteningly ferocious thing. Aggressive, unpleasant...it could be a bit like a war zone at times. Women can be odd over celebrity. I remember being shocked one day to find Lori, the Italian mother of my son, Conor, had acted just as she had with me with a dozen other so-called celebrities before we met. Same smile, same flirtatious talk, even the same adoring look in the same posture in identical photos with different men. Footballers, racing drivers, actors, they'd all been targeted identically. But I realise now how naïve I was. Right into my fifties.

NDR: Didn't you meet your present wife when she asked to be photographed with you?

EC: Well, I was into my fifties when I met Melia at a big Armani event in Los Angeles. Yes, she and a friend cheekily asked to be photographed with me. In fact Melia was so different from anyone I'd met before, so wonderful, that she quickly became the cornerstone of my life.

She was less than half my age and initially the difference did trouble me a bit. You see I had always lacked confidence and been a secret people-pleaser. I try to deny it but I do care what others think. I am still in recovery from that people-pleasing affliction. Anyway, I don't think about the age difference between Melia and me now. And it never affected her at all. Really, age is such an irrelevance. In relationships, in art, in music and in life it should never be allowed to matter at all.

NDR: How many guitars do you own?

EC: Not as many as I did. I have owned a lot. But I auctioned off quite a few for Crossroads, the alcoholic rehab centre I founded in Antigua some years ago. I sold 88 guitars in the first auction which raised $7.4 million. “Blackie”, one of my favourite guitars, fetched $959,500 which was a world record for a guitar, and my original cherry red Gibson ES 335 from the Yardbirds days earned my charity $847,500. Let's not get into which guitars are best for what or which are my all-time favourites. People always ask that. But there are no firm answers. I love all of my guitars in different ways.

The one thing people need to know is that you get what you pay for. Top quality guitars really are better and easier to play too. As I get older I sometimes get shoulder, neck and back problems from holding or wearing guitars and it is tempting to go for lighter models. But it's a dilemma. Because lighter guitars never sound as good. The heavier woods make a much better sound. The only answer is for me to play shorter sets. But let's move on.

NDR: Touring must be harder as you get older. How much longer will you do it?

EC: Good question. Touring is always hard. But now I am in my seventh decade it has never come harder! I am a bit deaf but I won't use any hearing aids because I like what sounds I do hear to be natural. And I get all kinds of physical aches and pains and digestive problems and I really miss being home. When I am away I pine for England more and more as I get older.

Robbie Robertson (of The Band) said years ago when they were breaking up that touring was “a goddamned impossible life”. He wasn't wrong. But, whilst some musicians – George Harrison was one – are happy to give up touring and just focus on recording work in the studio, I can't quite do that. You see because I am a perfectionist – obsessive, some would say – I have to retake and retake everything I am recording and still I believe I can do better. I really need to hear the response of a live audience just to be convinced my playing, my whole performance in fact, is good enough. And playing live there are no chances for a retake – which is good for me.

Not long ago I played three dates in Madison Square Garden with Steve Winwood when we did a lot of our old Blind Faith material. I enjoyed the performance and we got a great reception. There's been a big revival of interest in Blind Faith. But I don't intend ever to do major world tours again.

NDR: What other future plans do you have?

A number. I enjoy working with Robbie Robertson. I enjoy Robbie's company, and he is a great guitarist and an impressive producer and engineer in the studios too. He has played at the annual Crossroads Guitar Festival in aid of my Antigua rehab charity, which was good of him. We love playing Bo Diddley stuff and various blues numbers. We have similar taste and I hope to do more with him.

I also want to do more with Steve Winwood. I'd like to go with Steve and look again at our old haunts near the cottage he rented in the original Blind Faith days in Oxfordshire (it was Berkshire back then). That place was so inspirational for us. The infamous Blind Faith album cover of the young topless girl was set on the Berkshire Downs near Steve's cottage.

But I want to continue spending more time relaxing with my family.

NDR: Looking back, what have been some of the greatest highlights of your career?

EC: There have been a lot. One regret is that because of my addictions to drugs and later to alcohol, my memory of some of the best times is forever blurred. And my performances in those days were not what they could have been. It upsets me when I see young performers making the mistakes I made and even claiming drugs and drink enhance their work. This never happens. Music always suffers when people are on drugs or alcohol. Even the most hardened old blues or jazz performers will admit that in private. So, I suppose many of my better career times were since I finally learned to beat those addictions.

There have been some great moments at the annual alcohol-free New Year's Ball we play for AA in Surrey. And being in the original 1985 Live Aid event in Philadelphia was good. And the more recent celebration of the lives of the late Ahmet Ertegun and Arif Marden of Atlantic Records was pretty amazing. They were two inspiring figures who were so active and forward-looking in the music industry. Others there were Mick Jagger, Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young, Phil Collins, Bette Midler and Henry Kissinger - though Henry wasn't performing!

But probably one of the most memorable musical events for me was the Concert for George. As anyone who was there will tell you, the atmosphere was unique. So warm, so affecting. And it took place at the Albert Hall exactly a year to the day after George Harrison had died.

NDR: You were the musical director for that, weren't you? It must have been a mammoth task?

EC: It was big. But because all involved had so much affection and respect for George Harrison they went out of their way to be cooperative. And Olivia Harrison and their son Dhani took care of a lot of practical stuff along with our mutual friend Brian Roylance who has sadly now also passed on.

Jeff Lynne did a brilliant job overseeing the recording with help from some others who insisted on not being credited. And Joe Brown's daughter Sam organised and oversaw the backing vocals for the whole event. Sam Brown gave a storming performance of the last song George ever wrote too.

Many of the helpers insisted they didn't want a credit. I complied but I never like that. I always feel that, rather like teachers, we owe it to the public to help them understand who is actually responsible for what. Part of the educational process for the audience really. But Concert for George was a great experience. Such a feeling of togetherness and purpose. There were many of us there who are instinctively leaders - you might say people whose egos are big and who are used to doing things their own way - like Jeff Lynne and Paul McCartney and Tom Petty and the late Billy Preston. Plus myself, of course. But all pulled together on the night which was a demonstration of how much they wanted to do this thing. Of course, George would have said he didn't actually want the concert. But I think he'd have enjoyed the music and the comradeship there, nevertheless. I am very pleased and proud to have been involved.

NDR: How do you like to relax?

EC: I enjoy being at my Surrey home. I love the grounds and our rural life there. Our dogs, the gardens and my workshop and my art studio are all important to me. And I love country walks in the hills. Plus I enjoy picnics with the kids and fishing and shooting expeditions with friends plus as a family we spend time on my boat in the Mediterranean, often around Corsica or Elba. And of course I listen to music, usually old and classic blues. We also like staying at our homes in California, in Southern France and in Melia's home town of Columbus, Ohio.

NDR: Do you think you are finally more at ease with yourself, now?

EC: Absolutely. My family bring me huge joy. I could not overstate it. Thanks entirely to Melia and my girls, the last fifteen or so years have been the happiest of my life, by far. So much love and satisfaction – not from any achievement by me but simply from what has been bestowed upon me. At last I feel I am starting to be a bit optimistic about the future. Which is a wonderfully novel feeling for me.

Mind you, the family can never be the number one priority for any alcoholic like me. Because I know I'd lose it all if I didn't put my sobriety first. I continue to keep in touch with as many people in recovery as I can. Staying sober and helping others achieve and maintain sobriety will always be the most important thing in my life.

Though of course music has been key to so much for me too. Like always, 95 per cent of contemporary music is trash but the other 5 per cent is golden. And, as I say at the end of my autobiography, music will always find a way to reach us with or without big business, politics or anything else. Music survives everything. Like God it will always be present. It needs no help and suffers no hindrance. It has found me, and with God's blessing, it always will.

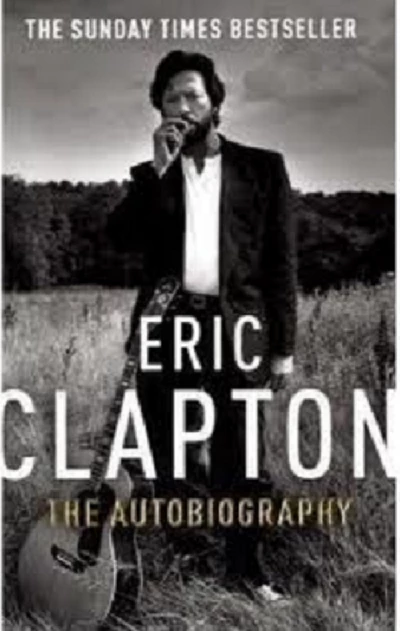

‘Eric Clapton – The Autobiography’, from Century Press is available in all good book shops. Extracts from this interview have been published in various other publications.

Picture Gallery:-