published: 9 /

7 /

2014

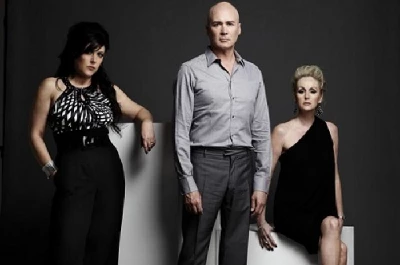

Lisa Torem speaks to Joanne Catherall, one of the vocalists with synth pop giants the Human League about her band's history and extraordinary career

Article

The Sheffield-formed band, the Human League, formed in the late 1970s and pioneered the mainstreaming of synth-pop music. They are known for infusing their performances with sharp vocals, brilliant costumes and contagious beats. The original line-up consisted of Martyn Ware, Ian Marsh, Adrian Wright and front man Phil Oakey. In 1979, they released studio album, ‘Reproduction’ and then ‘Travelogue’ the following year. When Ware and Marsh left the band in 1980, and formed first of all the British Electronic Foundation and then later out of that Heaven 17 with singer Glenn Gregory, Oakey, with a UK and European tour just two weeks away, scrambled to find suitable replacements. As luck would have it, he discovered Susanne Sulley and Joanne Catherall at a popular dance club.

The new line-up recorded several singles with producer Martin Rushent but it was ‘Don’t You Want Me’ from the award-winning 1981 album ‘Dare’ that made them international stars. Albums like ‘Hysteria’ (1984) and ‘Crash’ (1986) introduced their fan base to a different set of sounds, with the latter produced by American team, Jimmy Jam and Terry Lewis. Their ninth and latest album, ‘Credo’, came out in 2011.

Joanne Catherall has been a vocalist with the Human League since she and best friend, Susanne, got hand-picked by Oakey to join him on the road. Despite the usual headaches of touring, recording and revamping of their career path, Catherall has been a strong creative and business force in the trio’s legacy. In interview with Pennyblackmusic, she chronicled key events in the band’s early history, the many studio and stylistic decisions the band have navigated and how their professional and personal relationships have not only endured but blossomed.

The Human League has remained contemporary in a world in which technology constantly evolves. That said, Joanne Catherall has her own opinions about whether technology has been friend or foe.

PB: It was at the Crazy Daisy in Sheffield in the 1980s when Phil Oakey asked you and Susanne to be in Human League. What do you remember about that night and why do you think Phil was drawn to both of you?

JC: It wasn’t actually to join the group. The group was contracted to tour mainly around German army bases, but it split up so they needed new people to go with them to be able to keep the name of the group. So, Phil went out looking for people and Susanne and I were at the Crazy Daisy, which was where we normally went and we were dancing together. I think Philip thought instead of one person on the road, if there were two of us we could look after each other. In a club of very, very extraordinary people, we didn’t look too completely over the top, so he came up with a list of dates and we had to go home and tell our parents.

PB: That must have been a bit shocking.

JC: They were not happy at first to put it mildly, but I think things were very different then. I think nowadays with things like ‘The X-Factor’, with people wanting to be celebrities that people probably think that that would be quite normal now. In those days it wasn’t, and obviously our parents had visions of drugs and the kinds of things we used to hear about. But then they began to realise that Philip was an okay guy, so they talked to the school and the school agreed to let us out for four weeks off.

PB: But the group had had a male line-up until then. That created some challenges for you, didn’t it?

JC: Yes, they had an all-male line-up, and it was quite short notice that they were changing. It was army bases full of blokes and we got cans of lager and various other things thrown at us, but it didn’t seem that bad because we’d come out of the punk movement so there were always lots of things flying about.

PB: ‘Don’t You Want Me’ turned out to be a very successful song, but it’s often hard for a band to evaluate what material is going to hit. I imagine to the band at the time it was just one of a number of songs. It was Martin Rushent’s decision to record and release it. At what point did you realise it was the right decision?

JC: We were never not going to record it. The only problem we had with it at that stage was where to fit it on the album because it wasn’t like the rest of the tracks. So, obviously, the album being double-sided then, we decided to put it at the end and that was okay because it didn’t necessarily have to be a part of how the rest of it flowed because it was the last track, and after we tracked three singles with Simon Draper, who was the head of Virgin then, he wanted to put it out as a single.

And we were of the mind that people would get fed up with us– we’d had three singles in the Top Twenty and, because it was so different from everything else on the album, we’d never really thought of it as a single, so we didn’t really want it to come out but he was the head of the record label and he just overruled us basically. He put it out, and it took off in a way that we never in a million years expected.

PB: It’s a song about rejection yet you see people dancing to it. That’s what makes it magical. It’s bittersweet.

JC: Well, it’s loosely based on the story of ‘A Star is Born,’ which is a very sad film where the young girl overtakes her mentor and they’re in love and then they’re not. You’re right. It’s very bittersweet.

PB: I don’t know if the band gets enough credit for the often-deep quality of the lyrical content of your repertoire. Take ‘Seconds’ which was about the JFK assassination or ‘Heart like a Wheel’…

JC: We often got put on the list of bad lyrics, Top Ten Bad Lyrics. They put ‘Lebanon’ in because maybe they’re not listening to the lyrics because it’s a pop tune, and it’s only been recently that maybe reviewers and people that have interviewed us have said, “Actually, if you look at these lyrics they’re a lot deeper than it seems”. We wanted to do pop music because that’s what we loved, but at the same time without being too political also had other things which we wanted to say.

PB: The Human League has worked with a list of producers, which includes Colin Thurston, Chris Thomas, Ian Stanley, Jimmy Jam and Terry Lewis and Martin Rushent. Who really understood your vision?

JC: Obviously, Martin Rushent. We never would have had our first hits without him. He virtually became another member of the band. The old band had split up, and then Susanne and I were in and Jo Callis, (Ex-Rezillos member and Human League keyboardist and guitarist, 1981- 1986 - LT) our head songwriter, became involved and Ian Burden, who was a bass player, became involved. (Burden played keyboard with the Human League from 1981-1987).

It all fitted together, but it was like we needed one more piece because the songs were coming together but none of us were producers, and so you needed that extra little thing and Martin Rushent was a strange choice at that time because he’d not done that type of electronic music before. Simon Draper felt he was good with drums and that was one area that at that time was quite hard to do synthesizer-wise, and so we went to work with Martin and suddenly it was like we clicked. There’s somebody here who can do the part that’s missing.

PB: But you also enjoyed some Motown inspiration as well.

JC: I think that came from Jo Callis really. It was strange because he’s a guitar player and then when he was in the band it was like, “Now you’ve got to work on the synth.” So what he might have done a lot more lavishly on his guitar because he was so good at it, it had to come down to some very simple things because he couldn’t play the keyboard that well, and he was writing these great tunes that were really well simplified.

PB: You ultimately set up your own recording studio in Sheffield, which I imagine was partly a financial decision. Has that been an albatross or golden goose?

JC: (Laughs). I think it’s been both depending on our financial situation. We built the studio in about 1986 and the early 1990s were really bad for us. It was quite a struggle for us, but because we’ve always had so much gear in there we never really wanted to hire it out to people because a lot of the things are really old, and you don’t want somebody coming in and trashing it. So, it was quite hard during that period but we managed, and now it’s great because we mainly do live work now, and it has got a huge room that we can rehearse in, so we don’t have to pay someone else to rehearse. Plus it’s still a proper recording studio, so when we do record albums we can record them in there. So, in the long run it’s turned out to be a really good thing.

PB: You’re not in London as much as your fans would like.

JC: People get a bit weird with the London thing because it all gets a little bit like everybody and their grandfather wants to be on the guest list because they’ve been your biggest fan forever. We always play in London and we’re playing there at the end of this year, but we do more festival and one-off things whenever they come up. We have done festival things in London before, but we wouldn’t make a conscious effort to go there. That is just one place and we try to treat everywhere the same. Whether we are playing Scotland, London or down in Cornwall, they all deserve the same show.

PB: Phil Oakey has been involved with a number of side projects over the years such as Hiem, 1 Monster and has worked with Giorgio Moroder. How does this gel with you and Susanne, and do these projects influence the Human League’s fan base?

JC: I think the Giorgio Moroder stuff had an influence on them. Giorgio actually wanted Susanne and I to do ‘Together in Electric Dreams’ with Phil, but we couldn’t do it at the time. I can’t for the life of me remember why we couldn’t, and he actually said to us, “Well, it’s all right. I’ll get two session singers that sound just like you,” which he did. It’s quite bizarre when you listen to that track. You actually think that could actually be us singing. I don’t know where he found them. I don’t know if they have sound-a-likes like they have look-a—likes. Phil, however, was very keen to do it, and that was fine with us. We don’t have a problem with any of that sort of stuff.

PB: I saw you perform at the local Guinness Oyster Fest in Chicago in 2011 and the fans were quite impressed that you could perform such a visually stunning show on a relatively small stage in a typical urban neighborhood. Despite the informal nature of the setting, the band didn’t skimp on costuming, lighting or enthusiasm. It almost seems like the Human League can pack up and perform just about anywhere.

JC: I think what it basically comes down to is having a fantastic back catalogue, which means we can do a short thing if someone asks for like a forty minute set, say a little fest in Belgium or something like that or we’re doing the V Festival again this year for the third time. We can go and do that. A couple of weeks ago we were in the Isle of Man when the TT Races was on, and that was an hour and a half set. We’ve got a lot of flexibility because we’ve been going for so long and because we’ve got so many songs that people know. We’re not dependent on a big set.

PB: You’re going to performing at the Galtres Festival. Does performing at an outdoor festival present a challenge sound wise or logistically?

JC: I think the only challenge is when there’s really bad weather and that doesn’t normally affect the production as such because the stage is covered over. It’s hard because I don’t think any of us are actually festivalgoers as in people who would go to a festival to see it.

So, when we first started doing festivals years ago, we thought, “Ooh, this is weird.” Why do people come up here for the weekend? A few years ago when we did Bestival it was knee-deep in mud, I mean, literally, knee-deep and it was still absolutely packed. People were having a great time. And I’m thinking, “Oh, no, it’s giving me the heebie-jeebies.” But I think our crew can just cope with anything. Whatever is thrown at them they will make sure that everything is ready and that we’re on stage at the right time.

PB: My understanding of Galtres is that they don’t focus on just one genre so you might have fans at your set that came to see a band with an entirely different style. Is that a problem?

JC: I don’t think so. We’ve done some quite extraordinary festivals. For instance, in Germany, the Goth Festival, which is quite eye opening when you get there and we go, “Ooh. We’re going to go on and do something like ‘Human’.” The people booking the festivals must know something that we don’t and that went down very well, and I’m assuming that something like that will happen at Galtres.

I did a radio interview where the promoter of Galtres was also being interviewed. What he said is that they try to make it very local, not just local within ten miles, but in the Yorkshire sort of area or maybe North. So, we will just do our set and I think that people who come to festivals probably have more of an open mind. They’re expecting to hear different music ,and in a strange way it also helps us because then when we do our own show I think people come away from the festival – “That was a good little set there. Oh, they’re playing in December. We’ll buy a ticket and go see them there.”

PB: What albums will you pull from for Galtres?

JC: We’ll actually pull from the whole catalogue. I think there is something there from every album if we’re doing the longer – the 75-90 minute set. If it’s a forty-minute set, it tends to be just the hits.

PB: The Human League is known for a distinctive sense of style. Has that been internal or has this developed because of the influence of certain videographers or other professionals?

JC: It’s always been important to do a whole package, which includes the way you look. We were never going to be a group who said it’s going to be jeans and T-shirts this time. That’s not really what we are because we grew up with Glam Rock, Abba, people who really did make an effort with the costumes and, obviously, that goes into making videos. We’ve made videos with different people. We didn’t have a specific team and we’ve never really gone down the stylist route either.

Susanne and I try to coordinate maybe colour wise – she’ll say, “I’m thinking of wearing white this time”, but we couldn’t wear the same clothes because we’re so different - but we try to make some kind of co-ordination.

PB: How do you feel about the remixes of the Human League songs? They’re probably great to dance to, but do you ever wonder if the current generation is missing out on the energy of the original versions?

JC: No, not really because we did the ‘Love and Dancing’ remix album in 1982 mainly because Martin Rushent was travelling a lot to New York and going to the clubs and hearing a lot of that kind of stuff, and he wanted to remix the’ Dare ‘songs. We loved that.

But I think now the remixing has just become obligatory which is a bit tedious. You release a single, and it’s guaranteed that someone from the record company will say you need five remixes of that.

PB: Is the band involved in this process?

JC: No. The record company generally decides. Phil probably has input because he’s listening to more of that stuff. It’s not done in our studio. A lot of it is probably not even done in this country. It’s sent away, and then it comes back and the PR people say that remix is for that club and this remix is more geared for maybe the radio. And like you say, sometimes the actual song gets lost but I think that’s just the modern way of people doing things. Everyone does all the remixes.

PB: Do the three of you still go to clubs to check out the scene?

JC: No (Laughs).

PB: There were times when the Human League recorded consistently and other times there were gaps. Was this intentional?

JC: ‘Dare’ just came together very organically. We had a two-year gap before ‘Hysteria’; we were all in a panic because the first album had done so well so half the time we didn’t even know what we were doing. Coming up to ‘Crash’, we were in a bit of a pickle, the songwriting wasn’t working out right, it was all a bit of a mess and then Simon Draper at Virgin Records said, “Have you heard the stuff that Jimmy Jam and Terry Lewis were doing?” We said, “Yes, some of it is great, but we were of the opinion that they wouldn’t want to work with us because their music is not at all like ours”, but they were asked, and so we ended up in Minneapolis for three months. And the way they worked, they would say, “Oh, we won’t bother to work. It’s sunny.” On Sunday, they’d say, “We’ll all go to my house for a barbeque.” We were used to just being told to be in the studio by ten. So that was quite an eye-opener.

We recorded our 1990 album ‘Romantic’ in our studio and that was quite a bad time for us. The record label dropped us straight afterwards. Then we got signed by EastWest, which was a huge thing because it meant Ian Stanley produced our album and he had a massive influence on how that sounded. I would say he was like our next Martin Rushent for what he did for that album. We were with EastWest for a few years, and then that fell apart and we found Papillion, which was part of Chrysalis, and they wanted to give artists, people like us, who had had a career and perhaps couldn’t get signed to the big majors anymore and so we signed with them and did ‘Secrets’ in 2001. I think it was the day the album came out we got a message that Papillion was no more. It had been folded by Chrysalis. That was a really depressing moment because it was, literally, just when the album was coming out, and then we had a few years where we just toured and toured and toured.

And then we met Mark Jones from Wall of Sound, and we made ‘Credo’ in 2011. We’ve been very lucky. We’ve had some songs that people have liked along the way, and whenever we come around to the feeling that we want to end up in the studio and make some more music, then go touring for six months and go back to the studio, we’ve been very lucky because there’s always been someone out there that’s liked us and our history and said, “We’ll look forward to making an album with you.”

PB: So are you planning to go back in the studio soon?

JC: We don’t have any plans to go back into the studio. But after two or three years it’s always in the back of our minds. We do a lot of live work and, even if an album doesn’t do well in the charts, it perks you up, it perks the show up. It gives you a little bit of nervousness again. You’re going to play something new to people. You know all the other stuff but you’re going to put in two tracks, maybe, of new material and that gives you the butterflies again.

PB: The three of you have been through decades of performing and recording together. But from what I’ve read, it appears that when things get tough, you’re the rock. Do you think that’s true?

JC: Sometimes. I think we’ve all had our moments. What we always say is we’re fortunate that not all three of us have our moments at the same time. If not for that, maybe we would have split up along the way.

It tends to be that someone has a moment. They may be feeling down or despondent - What are we going to do from here? What shall we do? But as long as it’s not the three of us at the same time, I think we can cope because then I think the other two can talk the sense back into the person who is having the moment.

PB: And you have said that it’s not purely about the band. It’s about the people who depend on you.

JC: Our band and our lads are fabulous. They do a fantastic job. They put their heart and soul into everything and we don’t want to see them unemployed.

PB: Thank you.

The Human League will be headlining the Galtres Festival on Sunday 24th August. More information about the Galtres Festival and tickets can be found at http://www.galtresfestival.org.uk

Article Links:-

http://www.galtresfestival.org.uk

Band Links:-

http://www.thehumanleague.co.uk/

https://www.facebook.com/thehumanleagu

https://twitter.com/humanleagueHQ

https://www.instagram.com/humanleagueh

Picture Gallery:-