published: 3 /

4 /

2014

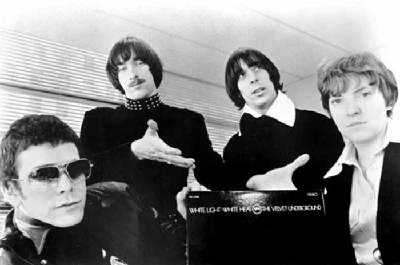

In the first part of a three part series Jon Rogers examines the recording and making of the Velvet Underground's 1967 second album, 'White Light/White Heat'

Article

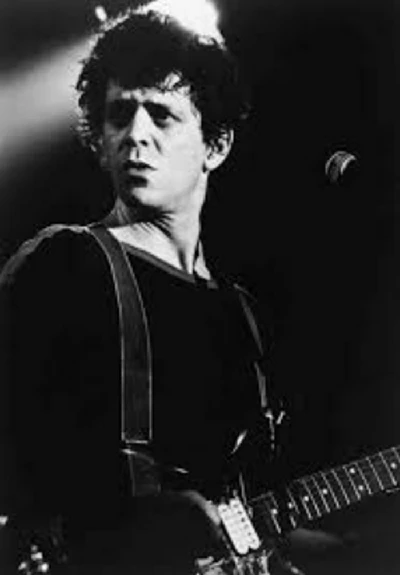

If, like many cultural commentators, 1967 is seen as the 'Summer of Love' when flower power was en vogue and all you needed was love and a nice kaftan whilst you ate mung beans at some hippie hangout on Haight and Ashbury, then the Velvet Undergound's second album, 'White Light/White Heat' was the antithesis of that philosophy. Whilst the hippies were wearing flowers in their hair and going to San Francisco to gobble LSD Lou Reed, John Cale, Sterling Morrison and Maureen Tucker detailed the seedier side of life and dabbled in speed and heroin.

After all, whilst it might have been the Summer of Love, it was also the year of the Six-Day War and urban riots in the ghettos as disenfranchised people started to fight back against oppression. In late July paratroopers had been called to calm the Detroit race riots, while over in New York Puerto Rican shops had been looted with two killed and around 300 injured in the disturbances. Violence erupted at an anti-war demonstration at the Pentagon with 250 being arrested, including the author Norman Mailer. Whilst there were disturbances in America, the country was getting further embroiled in the war in Vietnam as B-52s stepped up their bombing raids and there was increased used of napalm. By the time 'White Light/White Heat' was released in the US, the country had 486,000 troops in north Vietnam. Everything wasn't quite as cool and groovy as some might think.

Instead of discovering heaven in a wild flower the band detailed the hapless Waldo Jeffers, some macabre operation undergone by transvestite Lady Godiva - possibly gender reassignment? - speed psychosis; not to mention what Sister Ray got up to with those sailors 'she' and her drag queen friends picked up.

As Morrison later noted to Richard Witts in 1994: "We had little patience for flower power... We didn't fall for that sunny, California crap. What was annoying - among so many other things about flower power - was the way taking psychedelics was intellectualised as being 'mind-expanding' or somehow insightful, as though all those stupid hippies were on a spiritual quest instead of just taking drugs. It wasn't a question [for us] of seeing something as something else, but of seeing what it was in fact."

Many commentators have interpreted the brutal, hard-edged nature of the record as being a direct negation of the Summer of Love hippie ethos - a gritty, urban(e) response to the peace and love vibe, although as the likes of Witts recognises, the reality was not quite so simple. Taking a musicological approach, Witts in his 2006 book 'The Velvet Underground' looks at the musical influences of people like La Monte Young and his use of drones to draw a historical background to the influences on the album.

Richie Unterberger in his extensive book 'White Light/White Heat: The Velvet Underground Day-By-Day' sees the abrasiveness of the album drawN out by the frustrations of the band suffered over the past twelve months, such as the endless, unexplainable delays to the release of the debut album, the subsequent album then largely being ignored by critics and its commercial failure. Not to mention the split with Nico and then later Warhol. Those frustrations were then expressed, either consciously or unconsciously, on record.

Life in the Velvet Underground after the release of their debut album 'Velvet Underground and Nico' in 1967 certainly did not help matters. "Our lives were chaos," Morrison told 'Rolling Stone's David Fricke in 1994. "That's what's reflected in that record. Things were insane, day in and day out: the people we knew, the excesses of all sorts [...] I see that reflected in there. 'White Light/White Heat' was definitely the raucous end of what we did."

There were divisions within the ranks as well. Although 'Andy Warhol's Index' painted a rather grand 'happy families' scenario all was not right behind the scenes. The ever-present sniping between the band's front man Lou Reed and 'chanteuse' Nico escalated as the former lovers argued over who should be the focal point of the group. Anyway, the Germanic singer was never a permanent fixture and her time was up.

There were problems between the group and their so-called manager Andy Warhol. To the band, in particular Reed, Warhol was not devoting enough time to the band with Warhol's other art projects as well as film making taking up his time. Around the time of the release of their debut album Warhol was also busy promoting his film 'Chelsea Girls' and had gone to the Cannes Film Festival in France to try to launch the film on the international market - taking a large group of the Factory crowd and the band's hangers on with him. To the Velvets it seemed that Warhol had other priorities.

Whilst Reed was moving away from Warhol he was drawing ever closer to Steve Sesnick who was waiting in the wings to take over the managerial reins. Sesnick initially had wanted to strike a deal with the Beatles' manager Brian Epstein and his publishing company Nemperor. Epstein was interested but barely knew what day it was due to his alcohol and LSD consumption, washed down with sleeping pills and was really in no position to take on another band.

Reed did meet Epstein on at least one occasion with the Beatles manager giving Reed a lift uptown. The two had met at Max's Kansas City, along with Reed's friend Danny Fields, and Epstein, who had just returned from a trip to Acapulco, told Reed in the back of the car: "My lover and I spent our whole vacation listening to your record." Reed could only reply "Oh?" before Epstein added "Well, I like it very much," as he fondled Reed's arm. Nothing would come of the connection as Epstein would be dead six months later of a drugs overdose.

Sesnick instead decided to manage the group himself, and went about trying to bend the ear of Reed telling him he was the leader of the group, and trying to dazzle him by telling him what he could do for the band. With Warhol immersed in his films, Reed was only too willing to listen.

By the time Warhol was back from Cannes, Reed was ready to sever ties with the pop artist, leaving Warhol predictably hurt. "He called me a rat," Reed recollected years later. "It was the worst thing he could think of." Warhol simply tore up the contract and a few weeks later Reed joined up with Sesnick.

Sesnick's involvement would, itself, cause deep divisions within the band - Victor Bockris, in his biography of Reed, describes Sesnick as a "fast-talking, cigar smoking bullshit artist" - but the initial signs were positive as he got the group a spot on the Cleveland rock show 'Upbeat' on 8 January 1967 where they performed 'Guess I'm Falling in Love'.

The cracks already present between Reed and Cale, the two main songwriters in the band, were also growing wider. Antagonism between the pair had always been there as they battled over the direction the band should go in; Cale wanting to pursue his more avant-garde leanings while Reed wanted a relatively more commercial approach with more conventional songs, but with the introduction of Sesnick into the mix it just made the situation far worse. Sesnick pushed the balance of power firmly into Reed's hands which Cale strongly objected to and Tucker could see right through him. "He was honestly convinced that we could be the next Beatles," said Tucker. "He always talked up - never down. Of course, even I realised he was in it to get rich. He had such high, high hopes."

"Steven just drove a wedge right between Lou and me," Cale related in Bockris' biography. "That was his main concern to say, 'Look, Lou's the star, you're just the sideman.' Wrong, Steve."

An indication of the musical direction Cale was on and how that was quite far removed from the direction Reed wanted to go in is perhaps highlighted in the home recordings Cale did away from the Velvets. Cale had always done these ever since the band was formed, but the one done in May 1967 emphatically emphasised Cale's avant-garde credentials. The 26-and-a-half-minute ' At About This Time Mozart Was Dead And Joseph Conrad Was Sailing The Seven Seas Learning English Pt. 1' was, as with most of his experimental recordings, far too challenging to be put under the Velvet Underground umbrella. Any sort of notion of using a chord is dropped with Cale making his viola sound like some demented 'Clanger', high on acid, mixed in with tape manipulations using his Wollensak recorder. Morrison pitches in as he adds some scrapped guitar noise into the avant-garde brew.

Also recorded around this time is 'Terry's Cha-Cha' with Cale once again manipulating the Wollensak recorder and playing his Vox organ. Former Velvets drummer Angus MacLise helps out too along with the Terry in the title of the song, soprano saxophonist Terry Jennings who had played with Cale and MacLise in La Monte Young's group.

While the Summer of Love was in full flight in San Francisco the Velvets remained in New York and went into Mayfair Sound Studios on Seventh Avenue near Times Square in the second week of September to record their next album with the band doing some seven sessions over two weeks. It was the first time the band had been in a studio for around eighteen months.

The band had amassed a sizeable collection of new songs since the end of 1966 and had been making rough demos of 'It's Alright (The Way That You Live)', 'Sheltered Life', 'I'm Not Too Sorry (Now that You're Gone)' and 'Here She Comes Now' and working up other new songs, like the instrumental 'Booker T' and 'Pale Blue Eyes' and road tested them at live dates. 'Guess I'm Falling in Love' which had been recorded live at the Gymnasium in April and 'Foggy Notion' had also been in the band's set since mid 1966.

As Morrison stated in 'Uptight: the Story of the Velvet Underground' by Victor Bockris and Gerard Malanga: "The so-called Summer of Love was a lovely summer in New York City, for in addition to the usual eastward migration of the vapid chic set (comprising socialites, Arabs and whatnot) to the Hamptons, another and even more welcome exodus took place westward, to San Francisco. Inspired by media hype, and encouraged by shamelessly deceitful songs on the radio (Jefferson Airplane, Mamas and Papas, Eric Burdon) teenage ninnies flocked from Middle America out to the coast; hot on their heels came a predatory mob from NYC. Roughly speaking, every creep, every degenerate, every hustler, booster and rip-off artist, every wasted weirdo packed up his or her clap, crabs and cons and headed off to the Promised Land. This sleazy legion - like Harvey Korman's goon squad in 'Blazing Saddles' - then descended upon the hapless hippies (and their dupes) in San Francisco. And the rest, as the saying goes, is history.

"But behind them in Manhattan, all was suddenly quiet, clean and beautiful like the world of Noah after the Flood. If you hadn't seen a particular lowlife for a while, there was no need to inquire about his or her whereabouts: you knew where they all were, and had a pretty good idea of what they were up to."

"And so, at the height of the 'Summer of Love', we stayed in NYC and recorded 'White Light/White Heat', an orgasm of our own."

As Reed put it: "We wanted to go as high and as hard as we could."

While Cale described it in his autobiography 'What's Welsh for Zen?': "I think the songs were hypes. We always played loud music in order to get the symphonic sound, but the loudness was supposed to bring clarity, and that wasn't true of the second album. It was the inability to realise the value of expert objective opinion that slowed our progress over the years. When I think of the many wonderful producers who would have been available to us, it boggles the mind that we did not use them."

Once again the band used Tom Wilson as producer and brought in Gary Kellgren as engineer although the reality was that both of them had a minimal input to the creative process with both of them really there to tame the wilder aspects as of the band in order to get the music down on tape. Wilson seemed more intent on having a good time and would repeatedly disappear with a seemingly never-ending procession of ladies that he would invite round, although Cale seemed to like him, telling 'Creem' in November 1987: "He's a swinger par excellence. It was unbelievable, a constant parade into that studio. He was inspired, though, and used to joke around to keep everybody in the band light."

The reality was that Wilson, who had a pedigree having been behind the controls of Bob Dylan's 'Like a Rolling Stone' and helping Simon & Garfunkel to fame with 'The Sound of Silence', would set the band up and effectively leave them to their own devices and wander in and out.

"He [Kellgren] was completely competent," commented Tucker. "The technical deficiencies on the album are attributable to us. We would not accommodate what we were trying to do to the limitations of the studio. We kept on saying we don't want to hear any problems."

Similarly, Wilson had a job on his hands trying to keep a lid on things, as Tucker stated: "He [Wilson] was in there [the studio] but no producer could override our taste. We'd do a whole lot of takes."

"If you were a producer trying to tell us what to do that wasn't too good. What we needed in a producer was really an educator," as Morrison put it.

And the band worked quickly with Reed particularly proficient in getting what he wanted. Despite the tension between Cale and Reed the pair worked well together in the studio with Sesnick saying: "They worked together fairly well because of the speed with which things were done. Had they had more time who knows what would have happened? But no, there was no problem at all."

Any arguments that arose though were over which take to use with the members opting for the one that they sounded best on although there were no major problems with Tucker describing the session as "relaxed and straight ahead."

It is perhaps no surprise then that the 17-minute album finale, 'Sister Ray' was recorded in one single take. As Tucker remembered: "We knew 'Sister Ray' was going to be a major effort. We stared at each other and said, 'This is going to be one take. So whatever you want to do, you better do it now.

"And that explains what is going on in the mix. There is a musical struggle - everyone's trying to do what he wants to do every second, and nobody's backing off. I think it's great the way the organ comes in. Cale starts to try and play a solo. He's totally buried and there's a sort of surge and then he's pulling out all the stops until he just rises out of the pack. He was able to get louder than Lou and I were. The drums are almost totally drowned out."

That sense of improvisation permeates the record with songs never worked out fully in rehearsals with the band only bothering to practise the beginnings and endings with any song never played the same way twice.

"The songs we practised most - the truly polished pieces - we never recorded," remembered Morrison. "We knew we could do them, so there was no more interest. We wanted to see if we could make something else work. Our best stuff, about 80% of it, was either radically reworked in the studio or written there."

"Most of the recording was done straight through," recollected Cale in the March issue of 'Trouser Press'. "'Sister Ray' was one piece. 'I Heard Her Call My Name' and 'Here She Comes Now' evolved in the studio. We never performed them live. 'The Gift' was a story Lou had written a long time ago when he was in Syracuse University. It was my idea to do it as a spoken-word thing. We had this piece called 'Booker T' that was instrumental, so instead of wasting it we decided to combine them."

The exception to that basic premise though was 'Here She Comes Now' with the band making a demo version of the song in January 1967, possibly recorded at Cale's Ludlow Street loft apartment, along with four other songs. This demo version is performed in a lower key than on the later album version and has a more wistful melody to it, ending with a flourish from Cale's viola. A second take of the song is also recorded with what appears to be more fully developed and different lyrics with Reed emphasising the songs sexual innuendo with the line "if she ever comes now". Other songs recorded at this session include 'I'm Not Too Sorry (Now That You've Gone)', 'It's All Right (The Way That You Live)', 'Sheltered Life' and 'There Is No Reason'.

The band had also been working on 'I Heard Her Call My Name' and 'White Light/White Heat' before they were committed to vinyl with both songs featuring in their live set at least as early as May 1967 when they were performed at the Boston Tea Party on 26th and 27th. Also included in the set was a 15-minute song called 'Searchin'' which would prove to be a prototype for 'Sister Ray'.

Technically speaking the album is an utter failure. Instead of trying to lay down separate tracks for the instruments and vocals it was all done as 'live' with a "simultaneous voice", as Morrison put it. But technology at that time couldn't cope and there was leakage everywhere, so any attempt at mixing would be futile. Combine that with all the instruments cranked up to maximum as they all battled for dominance and a mentality of 'everything louder than everything else' and, sonically, it is an utter mess.

"Gary Kellgran told us repeatedly, 'You can't do it - all the needles are on red'," Morrison noted. "And we reacted as we always reacted: 'Look, we don't know what goes on in there and we don't want to hear about it. Just do the best you can.' And so the album is all fuzzy; there's all that white noise."

As he expanded for Spanish television in a 1986 interview with Ignacio Julia: "'White Light/White Heat' was a real frustration, because we wanted to do something electronic and energetic. We had the energy and we had the electronics, what we didn't take into account was whether it could be recorded. If we went into a studio now and did 'White Light/White Heat', it would work, because they have the equipment - then they didn't, so there's incredible leakage from track to track. There were ways we could have done it, if we had all played individually, but we didn't like to, we liked to play simultaneously and used voiceover live a lot of times.

"We didn't know the album was doomed until we actually mixed it down, because we would do the tracks and then you'd listen to them, track by track, and they sounded good, so you kept on going. The big surprise comes when you mix it down and then try to do a pressing. There's all this distortion and all sorts of [fuzz] and compression and all this leakage, a lot of white noise. There was so much commotion in the tracks that even the gain had to be reduced for the stylus when they cut it. The quiet things are kind of okay, but the major electronic efforts - 'I Heard Her Call My Name' and 'Sister Ray' - are not. 'Sister Ray' succeeds because I don't think anybody can perceive it any way other than it is, but we intended it to be a lot cleaner and crisper, so even that was a disappointment."

Cale agrees with Morrison's assessment, adding in his memoirs: "By that time we'd become a fully fledged rock and roll band from touring, and the unifying concept of 'White Light/White Heat' was really capturing that spirit. We were intent on recording this album live in the studio because we were so good live at that point. We played and played and played, and to keep that animalism there, we insisted on playing at the volume that we played on stage. We were working in a very small studio with no isolation so it was all this noise just smashing into more noise, but we felt that if we caught the excitement of a live performance on tape we'd have achieved our one aim. We never quite realised that there were technical problems involved in turning everything up past nine. The bass would get obscured and we'd be wondering where it had gone. The volume was on ten but you couldn't hear it."

Part of that idea of turn everything up to the maximum, certainly for Cale, was born out of a desire to emulate Phil Spector's 'Wall of Sound' which he linked to La Monte Young's notion of 'sustained tones'. Where Spector though built up his sound brick by brick and layer upon layer, the Velvets just blasted everything, all at once, creating a stream of dense instrumental sound where Reed's vocals and lyrics would be placed within it. The idea was to create "an orchestral chaos" where Reed would "spontaneously create lyrics", where 'Sister Ray' would perhaps be the best example of the band realising that. Speaking on the BBC Radio 4 show 'Desert Island Discs' in 2004 Cale said he wanted to create "a landscape, tapestry, of sound behind simple chords. I thought we could do what Phil Spector had."

Picture Gallery:-