published: 15 /

1 /

2014

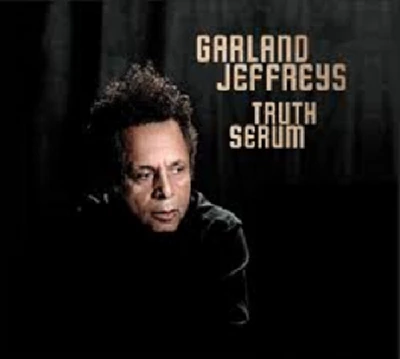

Lisa Torem speaks to acclaimed singer-songwriter Garland Jeffreys about his long musical career, latest album 'Truth Serum' and forthcoming tour of Europe

Article

Sadly the impressive Brooklyn baseball stadium where little Garland Jeffreys marvelled as Jackie Robinson made history got torn down in the 1960s, replaced by a building complex on which no baseball playing is allowed. But thirteen albums strong, the friendly singer-songwriter and dynamic showman remains busy making his own mark on American history and culture. Since the 1970’s, Jeffreys has steadily written palpable hooks and conscious-hammering lyrics. Consider ‘Miami Beach’, ‘Wild in the Streets’ and the track ‘I Am What I Am’ from his new album, ‘Truth Serum’.

Jeffreys, a curious world traveller, is a sort of American version of London’s Big Ben’; a much-appreciated symbol of strength, functionality and glamour. Although he has earned his musical chops, he has simultaneously delved deeply into race relations and never forgotten the allure of his native New York surroundings, interjecting songs such as ‘Roller Coaster Town’ – Jeffreys grew up next to the amusement park, Coney Island – and ‘New York Skyline’ with flashes of reggae and soul. His friendships and in-the- limelight collaborations have included the likes of Bruce Springsteen, Bob Marley and Lou Reed.

Jeffrey’s compassion and natural musical abilities come out clearly in our conversation – I even get to hear a few riveting stanzas at no extra charge! He’s excited about ‘Truth Serum’ and the talented team that made it click. He’s sending off his daughter, Savannah, to college shortly, and is grounded in a long time marriage to his wife, Claire. All in all, things are getting better and better as Jeffreys plots out a stream of touring dates and a well-earned place in the land of rock.

PB: What was growing up in Brooklyn like? How did the street corner phenomenon and your early musical influences inform your overall musicianship?

GJ: I’ll give you a sense of my history. I’m very good at telling my story, naturally. I grew up in the Coney Island/Brighton Beach/Sheepshead Bay Area of Brooklyn, which was quite nice because you were not far from the beach, not far from the water, and for a kid like me (and other kids like me) it was great because we had the water.

I went out fishing as a young kid and I’d work on the boats. In the summer, I’d go out in the boat and fish. I’d bring the fish home, clean the fish and that would be our fish for Fridays, because we were raised Catholic.

What was so great about that, in addition to the experience of doing these things, was the independence that I developed very, very early, and I’m very grateful for that because some people just don’t have that. I have that kind of personal freedom. I can move around within myself and in the world, and that’s why in the end I was able to develop a career in Europe – because I went to school in Florence. I was an undergraduate at Syracuse University in New York, and I was lucky enough to get on this program to go to Florence. I lived with two Italian families, who didn’t speak English so I became fluent in Italian. I’m still fluent, and it opened up the whole European world for me.

I have a career in Germany, Holland and Belgium, and now I’m doing it all over again, playing again in these places. I’ve been looking today at a map of some of the French shows I’m going to be doing down in the South.

I’m very pleased about all of that. It’s unique for an American artist to be doing all of that. I move around very well. If I’m in France, I can speak enough French to get me around. I have some very close friends in France and in other parts of Europe. When I say, very close friends; it’s like second nature. It’s like they’re here, they come and see me and I go to see them. I was the best man at one of the guys there in Paris; he’s the number one star of TV, Antoine de Caunes.

I guess I’m painting a picture of a guy coming out of Brooklyn, and, unlike anybody else I knew where I grew up, I developed a freedom because I was curious. That kind of experience of travelling and going to Europe and being accepted in this program when I was nineteen – nobody I knew had that experience -- not from Brooklyn -- so here I am.

I’m a married guy. I have a lovely wife and a seventeen-year-old daughter who is fantastic, who will be going to college next year. She is very much like me in terms of her own independence. What do I want to do for the rest of my life? I want to be onstage and perform and sing my songs wherever I can. I’m going to Japan shortly and I’m going to Australia shortly. I’ve been to Japan before, but I’ve never been to Australia and I’ll be doing a tour there which will be fantastic.

PB: You’ll be performing at a little town Kinross in Scotland. Have you ever performed in Scotland before?

GJ: No, I’ve never been to Scotland, and I’ve never been to Ireland, and I really want to go to these places.

PB: This town only has a population of about 5000 and is home to a castle in which Mary Queen of Scots was once imprisoned. It sounds like a big contrast to some of the other places you’ll visit.

GJ: I look forward to it. I know that Bruce (Springsteen, LT) – Bruce is a good friend of mine – is loving Ireland. I’ve never been there, and I intend to do shows and become very much a part of that.

PB: You’ve discussed your admiration of Frankie Lymon, Nina Simone, Frank Sinatra and David Ruffin. What stands out in your mind about these performers?

GJ: There were the great performers. A guy like David Ruffin – nobody can sing like him as far as I’m concerned. Ray Charles had a certain kind of voice, and he was absolutely amazing. What a musician!

David Ruffin was more in that soul pop world but what a singer! You had David Ruffin and Smokey Robinson ,but I would take David Ruffin any day. He had a phenomenal voice and great energy. The music I heard growing up was what my parents played at home. My father liked Louis Armstrong. My mother and uncle liked Miles, and my mother liked Ella Fitzgerald and Sarah Vaughan. I heard all of this as a kid, and my voice definitely absorbed and was influenced by them. I eventually went into the world of Little Richard and Frankie Lymon, who was my idol. We were the same size and the same age. I had some kind of fantasy; maybe I could be a singer back then. I’m talking twelve years old.

PB: Listening to Frankie, you felt that this could really happen.

GJ: There were two guys who were older than me. They were tall guys in the neighborhood, Stetson and Davey. They were giants. Physically they were much taller than me, and these were the guys I followed. They could sing that street corner stuff and I learned, but down the line I had a different kind of life.

I was fortunate. My father worked two jobs to put me through school, and he wanted me to go to college. He wasn’t even my father. He was my stepfather. So what kind of man is that? He was an amazing man, a working class guy. He worked two jobs, and I think about that often.

My daughter interviewed with Harvard a few days ago. She’s got about five of the best schools you could want. I just want to find a good school for her where she can continue her education. I’m watching this girl, and I know she’s going to be out of the house any minute now. She has a boyfriend. He’s very nice. We talk. He’s very respectful. They definitely have a real connection. I’m quite blessed if you want to say that.

My wife and I have been together thirty-two years. We have a real marriage. Very few people I know have what we have. When I think about the people I meet – I have a real marriage all these years. We’ve gone through the wars together – the personal wars between each other and the external wars. We’re true partners. It’s a lovely thing, and this is at the very centre, the core, of anything I do in my life.

PB: Your partnership?

GJ: My partnership. I’m fortunate to still be able to perform, I have my energy. I’m seventy years old.

PB: Were you surprised when ‘Wild in the Streets’ became an anthem for the Occupy movement?

GJ: I was happy about it. I guess I was sort of surprised. I’m rarely surprised (Laughs). Anything can happen. It’s a song that continues to be rediscovered and rediscovered. Generations pick up on it, and a lot of people like it. I was walking not far from where I live in Stuyvesant Town in New York, walking along the water one day and I see this guy.

He says, “You’re Garland Jeffreys. I’m a big fan of ‘Wild in the Streets’.”

I’d never seen this guy ever. He said, “I’m such a big fan of the record.” He was a young guy. You really really hope that anything you do is heard by another generation.

PB: Your material can come back any time. You always create a contemporary feel. But beyond that, I believe that you take social issues very seriously. It’s not a fad with you.

And you have done workshops with school kids on such topics too.

GJ: I used to do it up in Canada and I’ve done a few here. I would show a little clip. I had this little brain, and I would pass it around in the class, and from there I could talk about your brain thinking. One of the most important things that you can teach a young kid is that they, too, have the ability and capacity to make a life, to do something with their life. Than you can talk about different things and I’ll talk about my past, what I struggled with and what I became interested in.

I just wrote to someone on Facebook a little while ago, a woman who can’t get a job. I know the woman, and I told her just keep going on and looking. Just put yourself out there and one thing can lead to another. I’m always like that. If I can lend a hand to someone from my experience, it’s not complicated and it’s very simple.

I like the elderly. Where I live, there are a lot of elderly. It’s unusual for New York City, because it’s protected. It’s not noisy. You’re right on 15th, 16th 17th Street and 1st Avenue. You’ve got the river. You see elderly people in the spring and the summer and all year long. I like to reach out to them. “How are you? How are you doing? How’s everything? It’s nice to see you again.” A lot of times they don’t remember that you’ve seen them the first time, but you put your arm around somebody. I just love all that, you see. It’s the simple things that you can do while you’re waiting to do the bigger things. Do what you can. Take the time and take the moment. It always comes back to you anyway. You’re the beneficiary.

PB: On your new album ‘Truth Serum’ you used cassette tapes and recorders rather than digital equipment.

GJ: Right now as I’m sitting on the couch, I have a cassette recorder right in front of me. (Garland plays a few seconds of a strong riff on tape). At one point, I recorded this little riff, this little rhythm, and I like to do this because I got something I like. Some of these rhythms are very good, and I use them when I’m going to the next level with them. The cassette is really for dropping down ideas. Sometimes I carry it with me, but you can guess that it’s within two or three feet of me when I’m at home. I record everything I can, and sometimes I record a whole song that I’ve written.

And then I’ll go back, and I’ll be very surprised about how good some things are and how very clearly some aren’t really there yet. That’s the way I like to work because then I can get a couple of other players, go into the studio where I’m looking for better sound, better recording with four or five players like when we did the ‘Truth Serum’ album. One of the beauties is that I was working with some of the best players in the country.

Steve Jordan, on drums, is fantastic, as is Larry Campbell, on guitar, Brian Mitchell and I have become very close. He’s a fantastic keyboard player, who plays organ, accordion and harmonica, and the way he plays these instruments in the song is just fantastic: simple and clear. He makes it work and makes it fit, and there is a bass player and another guitar player from Boston, Duke Levine, who plays with Peter Wolf, as well.

So, I have the songs, and I have part of the song, and we go into the studio and before you know it we’ve got something. On the ‘Truth Serum’ album, that happened very quickly. I don’t think I’ve ever recorded so quickly and so efficiently.

It was at Brooklyn Recording. These guys know just what to play. You show them the rhythm and the chord structure, and then I go into the booth. The drummer counts off the song, and, before you know it, we’ve recorded the song with the vocal.

Most people don’t record it with the vocal. They record the vocal later. So you get the track that’s happening and the voice at the same time. You get the best of both worlds: great players, who are very soulful and who don’t need to record the song three or four times. You get it in one time with the vocal. And that’s how we recorded ‘Truth Serum’, more than any other record that I’ve made: very quick, very spontaneous with all the ingredients that you’re looking for.

PB: ‘It’s What I Am’ was written in tribute to Lou Reed, wasn’t it?

GJ: I make it a tribute to Lou Reed now. It wasn’t written as a tribute to Lou Reed. I love the song. I just love it. It’s the best song I’ve written in a few years. Subsequently days after Lou passed I started dedicating it to him in a couple of situations, not often. But Lou and I were friends for fifty years since 1961. We met at Syracuse University, and we started being friends through Delmore Schwartz, who was one of the professors and a great, great writer and he was very much a mentor of Lou. He showed Lou a lot.

Lou and I would meet almost every day at four o ‘ clock at The Orange in Syracuse, which I’ll be going to in about three or four days. This was for like four years, and in between I went to that semester in Italy.

I met Rudy Lombard. He started CORE, a group that stood for racial equality. I saw him one day just a few years ago in a park near here. But before then I knew him up in Syracuse, and he was very much involved with race relations.

You meet people and who they are and what they say to you and what you say to them can be very influential, even though it’s in passing. They say something and you think about it, and the next person you meet makes it gel a little further. Wow. That’s important.

When we were freshman in Syracuse nobody was talking about race relations because we were young and we had just arrived in college, but I met Rudy about two or three years down the line, and I was beginning to think about these issues. and Rudy was already there. So, that developed as part of my life, the music I made and the songs that I write.

PB: One thing that I’ve noticed is that when you deal thematically with race relations you might use a narrator or a graphic video to drive home a point but you, as a perfomer, don’t raise your voice. You don’t sound agitated. That seems effective. That seems to make people think.

GJ: I think you’re absolutely right. It’s something that I think I’ve discovered and I do rather well and rather naturally, and I think it’s very very important. I came to this conclusion early -- that if you want to send a message you’ve got to send that message out in the right way. You’ve got to think about that. How is that going to be?

On the ‘Don’t Call Me Buckwheat’ CD, the cover picture is of me in a baseball uniform. That automatically softens the story. It’s in front of Ebbets Field, the Brooklyn Dodgers Stadium, the day Jackie Robinson made his first game and broke the colour line. I was there. It was April 15, 1947. I was four year old.

I have a picture of me standing in front of the stadium with my father and mother, as well from that same time. Little did I know in 1947 that I’d be interested in those kinds of things. But I loved what it’s come to mean to me and what I need to do – I want to get that photo in the library in Harlem and a few other places. It’s an important issue and it’s a historical thing.

Not too long ago I was in Shea Stadium watching a game with Doc Gooden, who was the pitcher for the Mets at the time, and Nolan Ryan. With two great pitchers, everybody wanted to see that game. I stood up in my seat to get some franks, and a couple of guys from behind shouted, “Hey, Buckwheat, get the fuck out of there. Get out of the way.” That really upset me and I got up and I left the area. I was on the line, waiting, and thinking, ‘Don’t Call Me Buckwheat’. But I went home over the next couple of days and wrote the song, and it became the album, the title and the whole story.

Right now, my wife and I are working very closely together. We’re extending my career pretty well. I’m playing in Japan and Australia, Europe and a lot of people know about what I’m doing and what I’m known for. I’m reviewing and letting a younger generation know for the first time. It’s pretty exciting. It’s effortless. It’s just doing it.

Singing, “Don’t call me Buckwheat. Don’t call me ‘Nig, nig, nig, nig…” You tell the story. You put the words out. Singing, “Don’t call me blackie boy, your negro toy”…this is the way you do it.

PB: Many of us have either been subject to discriminating comments or been with somebody else and it’s infuriating. And explaining to kids that they may experience this and how to handle it is always a challenge. It’s a discussion that you may not want to have because you don’t want the world to be that way, but it often is.

GJ: You must educate your kids and when you have a few adults, who need an education, educate them, too. (Laughs). My daughter, Savannah, who’s applying to colleges, sent a letter to one saying that she wants to follow in the footsteps of her dad and help lift up the race, in essence. She talks about this when I’m around and when I’m not around. She goes to Stuyvesant, one of the top three public schools in the country, but it’s not without issues. It’s a very, very high Asian population. Black aren’t feeling comfortable and aren’t feeling welcome. These are young students. They don’t know what to do. They don’t know how to bring black kids into the situation. But my daughter does. She and this guy are co-leaders of the interracial movement there and she has her style, which comes from mine, in terms of imparting the information and the message.

I saw her talk to another kid one day. She didn’t notice I was checking her out. The way she dealt with the person was just fantastic. She’s a leader if she wants to be. I’m not trying to make her a leader. She’s got to come to a decision about what she wants to do.

She’s a musician as well. She plays and sings. I would like her to be a musician, but I keep my mouth shut. I want her to choose; herself. I told her, there are very few careers where you can get onstage, sing the songs that you wrote to an audience, who is paying to see you get the applause that you would like and where everybody thinks you’re terrific and talented (Laughs). I could go on like that. I said, “Keep that in mind now” (Laughs).

But she sees me at home. She sees me struggling. She sees me in conflict. She sees me going beyond the challenges and being successful. This is the real world.

PB: Thank you.

Band Links:-

https://twitter.com/evansthedeath

https://www.facebook.com/evansthedeath

Picture Gallery:-