published: 31 /

8 /

2013

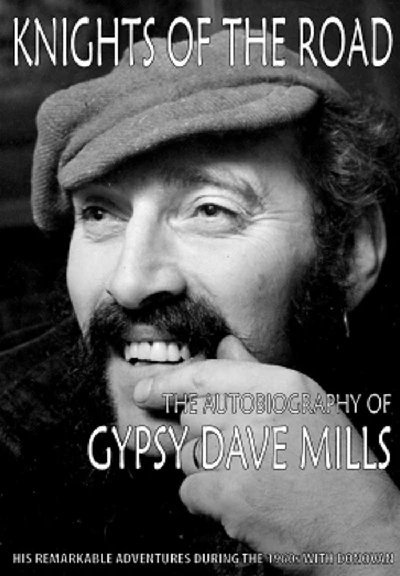

Lisa Torem speaks to British poet, songwriter and sculptor Gypsy Dave Mills about his new 60's autobiography 'Knights of the Road', which chronicles his years as best friend Donovan's tour manager

Article

Gyp Mills, better known as Gypsy Dave, is a British poet, songwriter and sculptor who teaches and works out of studios in Thailand and Greece and has exhibited his breathtaking bronze and marble statues worldwide. He is also folk singer Donovan’s best friend and has recently published an autobiography, ‘Knights of the Road: The Adventures of Gypsy Dave and Donovan’ which colourfully recalls and includes their early years as free- spirited travellers in the UK and in Paros, Greece.

In the book, Gyp also discusses his role as Donovan's tour manager and their collaborations on 'The Hurdy Gurdy Man' album. Many of their adventures are light-hearted, whilst some are riddled with irony. When rubbing elbows with industry legends, he is forced to make monumental career decisions.

When speaking by phone with Gyp, his unique and natural storytelling skills, generally punctuated with laughter, became immediately apparent; Descriptions of dangerous and random encounters with locals and vagabonds from the 1960s and beyond flew from his tongue as if he were back in the psychedelic trenches.

PB: Gyp, you have many talents, but I’d like to start by talking about your incredible career as a sculptor. First, you modeled for David Wynne’s sculpture ‘The Tyne God’, and that event ultimately led you to becoming a sculptor yourself.

GDM: What interested me was watching something come to life from nothing. That sculpture was done directly on an armature of metal with Plaster of Paris. Bill, his helper, was mixing it in barrel loads. David then just sculpted with it directly on the armature. It was just phenomenal. I loved David’s work before that, but actually being a part like that and actually seeing the whole thing in front of me was just magic.

I loved form more than I realized. Talking to David in his studio about many things to do with art, I came to see how deep were my feelings for sculpture. Quite remarkably, David knew I was a sculptor long before I attempted my own piece and told me so. I knew how serious he was with anything to do with sculpture, so this intrigued me no end and made me start my first piece in the hope he was right.

PB: Some of the titles of your pieces are very poetic, for example: ‘Dissipating Tears of a Fallen Angel’ – it is as though you brought your lyrical skills to the art of sculpture.

GDM: That is because my works really do say something. I’ve written down somewhere all my thoughts on my pieces. I don’t know if I really want that out. It’s quite nice when people see a piece and then just pick up their own things from it. I thought it was very important to give each one a title, which would give people some hints on my ideas because we’re from the 60's and we need to say something (Laughs).

PB: It is quite miraculous to take a slab of marble and create such art. Did you have an image in your mind of what you would end up with before you began?

GDM: With me living on Paros where the most beautiful marble in the ancient days came from Lyknitis, it was inspiring. That marble has all gone now, Napoleon had the last big piece for his tomb, but the ancient sculptors had it dug out from a vein that was about the size of two ceilings high and quarter of a mile long. They took marble from here for two thousand years, and what little there is left now is a national treasure. Quite rightly, too, as it is the most beautiful marble in the entire world. I did not use any of that because on the island itself there is loads of other marble. Sometimes I even found wonderful pieces in fallen down walls, in my garden – I even dug some great marble from my grounds.

Choreography - You see you make a dance with the piece and it’s just wonderful and the piece tells you so much – I never work from blocks, only with my huge ones. I don’t know if you’ve seen my spheres – with those, I have to work from blocks because they’re more mathematical.

When you’re cleaning out a piece of marble - taking away the pieces that you can’t use because they’ve got some mark in them or something - at certain times they start telling you things. That’s why I say you can dance with a piece. And once it starts telling you, it takes so long that you have plenty of time to think about things, and then you’d be in there working away and it would tell you something, and then you’d have other ideas and other ideas. Bloody hell, the piece actually told me what it wanted to do.

I don’t do it at the moment. I haven’t done any sculpture for a long time. The last piece I did I did for Donovan when he had an exhibition in Greece for the Harvard University there, in the ancient Greece course they do. He had asked me to do a harp.

PB: You’ve recently published ‘Knights of the Road’ – your adventures of traveling with Donovan and assorted other characters. Don had written part two of his own autobiography recently and, of course, mentioned you. Had you then thought about collaborating?

GDM: When I helped Don with his autobiography, we spent about six weeks in Greece working on it. I actually wanted to remind him of the old days. So I started writing stories down so he would remember, and he loved the stories so much that he phoned up his publisher. He said, "Look, let’s forget what we’re doing. Let’s Gyp and me write an autobiography together. It would be wonderful - Gyp’s stories and my stories." The publishers thought about that for a minute and said, "It’s your story we are writing so to hell with Gypsy Dave."

The main guy who was helping Don, said, "Let me have the first refusal on it, will you, old chap?" This got me thinking so I gave it a go (Laughs). It was a bit like the way David Wynne had first mentioned my sculpting ability.

PB: Wasn’t it a challenge to recall the events and the characters you met so long ago?

GDM: Well, you might not have at the time, but I discovered in myself the ability to bring it all back years later and had a great time remembering my youth after so many years had passed. I have lived a hell of a life really as you can tell if you read my book.

PB: How do you think your friendship with Don has survived as long as it has?

GDM: The secret is that we both love creativity. I’ve always loved his songs and his creativity, and he’s always gotten into mine as well. We’re two lads from nowhere on a council estate. I was born in London, and he was born in Glasgow in the worst areas, and I was born in not such a good area.

Both our parents moved out to try and improve their kids’ lives. His family moved to Hatfield and mine to Hertfordshire, too, and I suppose, from those early beginnings, none of us thought we’d be anything, artists or anything. Don has had no training whatsoever with his music. I’d had no training, really, apart from David encouraging me. Otherwise, we’d done this thing on our own. We found it in our hearts. That’s basically what will keep anything together. Artists are supposed to live long because they have something a bit bigger than themselves in their personal lives.

PB: You say in the book that when Donovan started achieving fame, he confided in you that many of his friendships became strained. Perhaps some of those people were jealous.

GDM: I think it’s just human nature. Unfortunately when someone starts doing something better than you, people become frustrated most probably with themselves. If I hear someone has something good happen to him, I’m there. And if I see someone with true creativity and talent, do something, I’m very happy for them. It’s a pity. It’s something in human nature. We have to change that in ourselves.

PB: As young men travelling you had a lot of freedom, but you were living on the edge quite often and sleeping in the oddest places at times…would you do it the same way?

GDM: Don and I still find that those early days, regardless of what has happened to us since, were almost the best days of our lives. We were poor, we had no worries and we had nothing. We wanted to live life, see what it was all by ourselves and talk our mouths dry with what we considered the important things in life.

Youth is a wonderful time. The person we become in youth is the person we stay even though we might try to hide it; it’s actually still there. And, no, I wouldn’t do anything differently, ever.

PB: Back when Don played at the English pub, The Cock, with friends like Mac Macleod, what was the audience reaction?

GDM: Donovan had something magical about him in the beginning. And when we went out bumming with the few tunes we had, and me with me silly comb and paper kazoo, we were surprised that people would give us money but I didn’t realize to the full extent the magic Don had. He had it from the first song he ever sang. It’s still with him, actually.

PB: There were those comparisons to Dylan, which I didn’t quite get because Dylan had that scratchy voice and Don had a gentle presence and came across as a poetic type.

GDM: Absolutely. I’ll tell you what it was. In the days when Don was compared to Dylan, it was actually through their likeness to Woody Guthrie that was truly the problem. Dylan, funnily enough, was never compared to Woody though he really did try to mimic him in many ways. I don’t know to this very day what Dylan’s real voice is like. Even Dylan’s name is not his own - he took that from his deep respect for the poet Dylan Thomas.

Dylan was from a time subtly before ours when its influence was mostly wine and all sorts of booze. Our time was influenced through our use of smoking dope, which made us a little bit more thoughtful, a little more creative in a sense.

PB: You collaborated with Don on ‘A Sunny Day’ and ‘The River Song’ on 'The Hurdy Gurdy Man' album and wrote, on your own, ‘Tangiers’. Your lyrics are quite visceral: ”Cutting nettles that are hiding petals bright…”, for example. You worked well together.

GDM: Yes, that worked quite well. It just happened actually. We were just sitting in the woods one day near his house, and it just came out. I said, "Actually I’ve got this," and I sang him ‘Tangiers’ and after that we worked on ‘Sunny Day’ where he worked directly from my poem. Then he said, "Listen, Gypo, I’ve got this little tune going ‘round in me mind." Immediately the words of ‘The River Song’ came into my head - I have never written them down on a piece of paper yet. Sixteen years after this time, they used my song ‘Tangier’ in a movie ('Castaway', 1986 - Ed), which helped me a lot when getting the royalties as me and my girlfriend Rita were stony broke by then.

PB: What instrumentation was used on ‘Tangier’ to give it that haunting sound?

GDM: I think it might have been Danny Thompson (Nick Drake, Richard Thompson - Ed) on his fantastic bass, and I think he used a bow on it. Those days when I wrote a poem, I had a rule that each line that came out would not be changed, so I would get a line down and then let the next line enter at will and then the next line would flow. It made for a rhyming style of poem that was very full of spontaneity and very youthful. Funnily enough, the other day I wrote my first poem in about thirty years; it was a little more contrived though.

PB; Producer Mickey Most often paired his acts together and paired Donovan with future members of Led Zeppelin for ‘Hurdy Gurdy Man’. How did you feel about those arrangements?

GDM: They were just phenomenal. That was John Cameron (Don’s musical director, who co-arranged ‘Sunshine Superman’ and arranged ‘Jennifer Juniper’ and ‘Epistle to Dippy’ - Ed) who did all the arranging. Together John and Don worked so well.

PB: Was the match with Mickey Most good for Don?

GDM: It was a wonderful match. When someone starts writing and starts doing things – like a sculptor – you never know where it’s going to go, and Don started to go more towards some upbeat and rock beats, and at that time Mickey was the perfect guy to go and do it. It was a totally different feel from Don’s other musical stuff.

What was amazing about those times was that every single song was totally different from the last one. You don’t get that these days. They want one album with one song repeated and repeated and repeated with different shades of colours on it. In those days, you could have made an album with every single song. It was a phenomenal time for music and the arts and everything.

The main reason I wrote my book, ‘Knights of the Road’, was to explain to my son Matthew something of my youth and times. I did this mainly to get him to understand why it was so important for me that he left the safety of our home. By then we were living on the Isle of Paros, Greece, where he quit our home by the age of 16 and a half. He did stand on his feet from that tender age and did very well independently of me, which was wonderful considering the limited scope he had on a little island. It made me very proud of him. He knew this ,but I always felt he thought it a little strange of me.

Years later he was to die of cancer. The cancer got into his bones and he went downhill very fast and I just managed to come from Thailand to his hospice in time, but I had with me the nearly finished autobiography, which he read two days before his death. The really lovely memory for me from all the heartbreak of that time was Matthew coming from his hospice room with the book in his hands, saying, "Bloody hell, Dad, you really can write." His next sentence was "No wonder you wanted to kick me out so young!" and then he gave me a hug. Anything that happens to the book from then on is just cream.

PB: Between 1965-1968, Don had written eight albums. Was being his personal assistant/manager really hectic and exciting or overwhelming?

GDM: Throughout all of those things, we had the most wonderful time. When you’re on a creative buzz like that, things happen. Don was on a roll from the 'Ready Steady Go' days. It was phenomenal but exhausting – the huge tours that we did. I would hear him sing and play to packed audiences. He really was amazing.

Of course, in those days nobody knew that there was anything wrong with arriving at a place at two in the morning when your personal clock told you it was two at night. So, you just arrived either in the middle of the night or early in the morning, and you just got on with it.

The number of people one meets in the world – we had thousands and thousands and thousands of people we met, and Don was an absolute caring gentleman through out those things. I was always in the wings listening to him at every bloody concert.

Don used to sing his songs as though he’d just written them. He had a phenomenal memory. That’s not been mentioned much. I think he inherited it from his father. He used to read monologues, which he would remember, of twenty pages. Don had that same memory. It’s more than probable I will write more from the different periods of my life. In this book it seems like rags to riches, but it was really rags to riches to rags to creative riches to rags to etc. It’s possible I have a couple more books in there somewhere. Let’s see how this one goes. I have lived a very full and charmed life.

PB: You made some interesting business decisions with Allen Klein and Chas Chandler.

GDM: I loved Chas – he was such a lovely fellow. If I hadn’t been so involved with Donovan, I might well have got involved. I thought Jimi Hendrix was an unbelievable talent. Yvonne and I were there the first day he played at the Bag of Nails, where my ex-wife had painted the mural over the bar. Yes, strange to tell, I did turn down Allen Klein’s offer, not of ten percent of the Beatles, but ten percent of his business deal with the Beatles, but somehow I was right with my premonition so I have never had any regrets.

I hope that didn’t come across in the book as being a bit strange – some people think it is - but there are a lot of psychic things that go on in the world. I had never told that story to anybody. I certainly did not tell Donovan about Chas’s offer because Chas told me not to…I was Don’s personal manager, but I was his friend first. Of course, Chas was always Jimi’s personal manager and I would have been more of a road manager if I had taken on the job.

PB: What are Donovan songs that one must hear?

GDM: His very first one was wonderful – ‘Catch the Wind.’ ‘Universal Soldier’ by Buffy St. Marie, a very important song at that time, and ‘Lalena’, which not many people talk about. I liked it, but I never went overboard over a very popular song ‘Atlantis’ even though it was a very big song for him. I must admit he made the most of the song.

Don’s fantastic on stage. He gives all of himself, always. I must have been to thousands and thousands of his concerts, and I would say 99.9 percent of them were brilliant.

PB: What do you see yourself doing in the next five years?

GDM: I now live in Thailand and I have a studio, which I was supposed to work in and a little school there, which I was supposed to get students for but none of these things worked that well because the world has changed so much. There’s no money out there for students. So that didn’t work.

But now I’ve got some condominiums right out by the sea, and it reminds me of somewhere in Devon and Cornwall I want to get back into my sculpture. Of course, I can’t do marble anymore because you’d need a big studio for that. I’m hoping, however, to start a few quarter life-size sculptures in clay to be made into bronze pieces of classic figures but using Oriental female figures, if I can find young ladies to model for me; not easy in Thailand. The ladies are so conscious of their nude figures, God knows why - they are so beautiful. I’ll see how that goes. And I want to keep writing and maybe get back to my poems. I used to write some children’s stories, as well.

PB: Like Sandy Lea.

GDM: Don actually used that name in a song once. Do you remember Sandie Shaw?

PB: No.

GDM: She was a singer. She came in barefoot. In the book, I said it was a lady who took me to a sandy lea, so that’s where that name came from.

For my son, also, his middle name was Sighdawn Mills when he was born, which was a name I wrote in another children’s book. I loved the name so much that I named my son Matthew Sighdawn Mills. When he was born, you know, you’re not allowed to invent names, so the guy said, "You can’t have this name. This is not a known name." I said, "But his mother’s Swedish and that’s a Swedish name." He said, "In that case, we’ll put it down." It wasn’t, of course. It was a total lie, but I loved that name…

PB; Thank you.

Picture Gallery:-

Visitor Comments:-

|

|

3807 Posted By: Lee, Kingston PA on 14 Mar 2023 |

Lenny Kravitz dodged a SERIOUS legal bullet since "his" Let Love Rule was stolen from Donovan's Atlantis

|