published: 31 /

7 /

2013

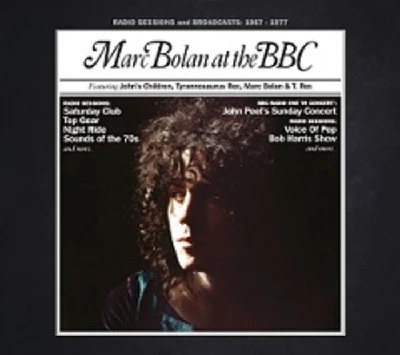

Adrian Janes looks at new Marc Bolan six CD box set 'Marc Bolan at the BBC: Radio Sessions and Broadcasts 1967-1977' which compiles together music from almost across his whole career

Article

The six CD box set 'Marc Bolan at the BBC: Radio Sessions and Broadcasts 1967-1977' ranges over almost the entire span of Marc Bolan’s career apart from his very earliest efforts. The first two discs comprise songs from BBC sessions recorded by John’s Children and Tyrannosaurus Rex. CD3 captures the completion of the move into the electrified form of the band, now known as T.Rex, which starts to emerge towards the end of the previous disc, and the first fruits of large-scale commercial success with versions of ‘Ride a White Swan‘ and ‘Hot Love’. CD4 represents the zenith of Bolan’s popularity, with a further version of ‘Hot Love’ plus recordings of ‘Get It On’, ‘Jeepster’, ‘Telegram Sam’ and a couple of tracks from the best-selling album ‘Electric Warrior’.

The fifth disc also contains versions of several hits (from ‘Metal Guru‘ to ‘The Groover’), but creatively and commercially it charts a gradual decline. Disc 6 is the least satisfying of all, replete with the formulaic (‘Truck On Tyke’), the uninspired (‘Zip Gun Boogie’) and covers or virtual covers (‘Do You Wanna Dance’, ‘I Love To Boogie’). A well-illustrated booklet with a detailed introduction by Bolan biographer Mark Paytress and dates and locations of the sessions completes the package.

In John’s Children Bolan was featured as a guitarist and writer, but his voice is only heard on alternate verses of ‘Hot Rod Mama’. This is understandable - he was drafted into the band as a guitarist and songwriter - but also unfortunate, as front man Andy Ellison’s uncertain warbling undermines the band’s Who-like energy.

The Tyrannosaurus Rex songs are prefaced by a brief Bolan jingle for John Peel’s ‘Top Gear’ show. (One of the qualities of this compilation is that it uses such material to complement the songs, along with a smattering of interviews from various times which give a sense of Bolan’s sometimes fantastical thinking about his career.) A startlingly large number of these songs (and the occasional poem) are taken from Peel programmes. Nowadays it would be greeted with great cynicism should a DJ have as unashamedly close a relationship with a musician as Peel did with Bolan in the late 60s (and it raised some eyebrows even then). Not only did he have Rex play a large number of radio sessions, but he insisted that they were part of the deal for anyone booking him as a live DJ. He also alludes on air more than once to socialising with Bolan. None of this is to cast aspersions - Bolan was a friend (at least for a few years), and as a DJ Peel was ideally placed to help him - but it seems indicative of a more innocent era and attitude.

That same innocence, in a musical sense, is beautifully reflected in the Tyrannosaurus Rex songs. From the electrified rawness of John’s Children, Bolan moved to a style based around spirited acoustic guitar, his extraordinary soulfully bleating voice and Steve Peregrine Took’s vigorous percussion and vocals, which on a number of songs interplay imaginatively with Bolan’s and are an aspect of the band which tends to get overlooked.

I don’t think Bolan has ever been quite given his due for the uniqueness of what he composed in those years. The enticingly bizarre titles, such as ‘Frowning Atahuallpa (My Inca Love)’, ‘Chariots of Silk’ and ‘Salamanda Palaganda’, demand and receive a special music which seems drawn variously from folk, blues, traditional Indian and rock and roll.

'Conesuela’, for example, moves from a verse with a yearning folk melody to a chorus driven by almost Eddie Cochran-like strumming.

The actual lyrics are often hard to make out (although after one song Peel assures listeners that doing so is “well worth the effort”), but an important part of the Tyrannosaurus Rex effect is the musicality of the words. If the comparison is not too high-flown - and Bolan did consider himself a poet - it recalls Dylan Thomas’ tendency towards sound over sense, except that while Thomas aimed for verbal music Bolan had the advantage of actually being a songwriter, melting words and music together as his voice becomes another instrument.

Took’s departure and his replacement by percussionist Mickey Finn indicate a move towards a more basic sound. Finn lacked Took’s abilities, apart from which Bolan was increasingly bringing electric guitar to the fore. Responding to the ‘guitar god’ tendency of the time, he used songs like ‘Elemental Child’ to indulge in long work-outs which regrettably proved his dexterity rather than a threat to the likes of Hendrix or Clapton. The inclusion of three versions of this song exemplify the trap that sets such as these often fall into, the privileging of completeness over quality.

On the other hand the urge for completeness means interesting comparisons can sometimes be made. One instance is the contrast between the acoustic ‘Debora’ of CD1 and the electric one towards the end of CD3 (part of a December 1970 live concert hosted by John Peel, by which time Steve Currie had joined on bass). The urgent delicacy of the earlier version is rather lost in the strident guitar of its successor, although it’s impossible to obliterate the song’s basic charm.

The fourth disc begins with ‘Woodland Rock’ and ‘Beltane Walk’. The titles still suggest the Tolkein-besotted hippie, but the music of the former is pure rock and roll revival (abetted by Bill Legend, now on drums, thus completing the classic T. Rex line-up), while the latter draws on these same roots but with a sharper guitar sound that makes it more contemporary. As noted above, this disc also has versions of several major hits: the high quality of the recordings and the faithfulness of the playing and singing make them almost as good as the official releases. It could be argued that this faithfulness shows a lack of inventiveness: but why radically change songs which simultaneously have power, conciseness and popular appeal? This may be what Bolan felt, although as radio interviews of the period demonstrate he was also picking up hostility for reliance on an alleged formula.

He continued to face this charge, exemplified on discs 5 and 6 in some back-handed compliments from Brian Matthew (“Meanwhile back in the charts - just”) and a somewhat testy encounter with Nicky Horne, someone not exactly known as the Jeremy Paxman of radio. Although the earlier discs do indeed show more variety and originality, hearing tracks from the last three years of his life makes clear that he did try to experiment and change. One obvious example is the soulful edge introduced by having black female backing singers, in particular partner Gloria Jones (writer of ‘Tainted Love’). Keyboards also became much more prominent, with Bolan’s guitarwork taking something of a back-seat and his lyrics generally becoming more minimalistic (though the verses of ‘Teenage Dream’ evoke his longstanding love of Bob Dylan).

So it’s hard to deny on this evidence that he implemented significant changes in later years that seem to have been missed at the time, perhaps because he never changed as radically as his friend and rival David Bowie. The real problem is in the relative weakness of the material, although the brooding, echoing ‘Explosive Mouth’, sax-smeared ‘Space Boss’ and shuffling groove of ‘Dreamy Lady‘ are all good if not inspired. Rounding off with ‘I Love To Boogie’ and ‘Celebrate Summer’ (the latter from August 1977, just weeks before he died in a car crash) don’t augur well creatively.

Throughout his career Bolan evinced a deep love of 50's rock and roll, and it runs like a seam through this collection. If these two songs (and 1975’s ‘New York City’) are anything to go by, he was conservatively returning to his roots as if in search of a renewed sense of musical security.

Against this, he was one of the established stars who was quick to encourage punk, touring with the Damned and having groups like Generation X on his TV show ‘Marc’.

In turn, at least some of the new bands acknowledged his influence: Siouxsie and the Banshees covered ‘Twentieth Century Boy’, while an intriguing aside in Richard Hell’s recent memoir notes that “Tom (Verlaine) and I both appreciated Bolan, digging the ‘Slider’ LP for instance”. If he had lived, perhaps greater exposure to the younger bands would have given him a new lease of musical life.

Committed fans are of course the most likely audience for sets such as this, with its multiple versions of some songs and the occasional inclusion of material that is frankly baffling (notably ‘My Baby’s LikeaA Cloudform’ and ‘Funk Music’ that can only be here because of their scarcity - not only are they nothing special, but the sound quality is so poor that they sound like they were recorded off the radio rather than for it). On the credit side there are good versions of many Bolan classics which, coupled with the interviews in which he is often engaging even if prone to self-delusion, make this something of an aural documentary. It may not be a ‘best of’, but the picture of Bolan in both his achievement and his decline is that much more rounded after listening to it.

Picture Gallery:-