published: 25 /

5 /

2013

Paul Waller speaks to Roger Miller from seminal Boston-based post-punk act Mission of Burma about his group's influential early releases, their reformation after two decades apart and latest album, last year's 'Unsound'

Article

By all accounts Boston’s Mission of Burma should have had their day. Indeed Roger Miller, Peter Prescott and Clint Conley are all in their late fifties or early sixties.

In the early 1980s their first couple of records laid the groundwork for the majority of post punk that followed in their wake. After the release of the ‘Signals, Calls and Marches’ EP (1981) and 'Vs' album (1982), Miller's on-going problem with tinnitus prematurely halted the band in 1983 who were by all accounts on the brink of a breakthrough of sorts, be it in an underground and independent way.

Some two decades later the band reformed, not for financial gain but simply because they could. There was unfinished musical business to attend to, and after the release of their comeback album ‘ONoffON’, released on Matador records in 2004, the band once again found themselves with a fan base that wanted to not only be challenged but wanted to be challenged in the loudest way possible.

Pennyblackmusic spoke to Roger Miller about Mission Of Burma’s latest record, last year's ‘Unsound’. It has been greeted with universal acclaim by the press and the fans that have heard it. Now the record has been out a while we wondered what it felt like now that the band has finally been accepted?

RM: Well, we didn’t know what would happen. It was one of those records where we said damn the torpedoes, full speed ahead! We said we would do it the way we want, and make it a little bit more crazy and out of control than the last one. We were just happy that people liked it so much. We have no idea how people are going to respond, so we are just happy and grateful if you want to know the truth, and with Fire Records behind us we are now touring over in Europe. We were never successful before, so now we can go over and play and get paid and people like it.

PB: Since the dissolution of the band in the 1980s, it wasn’t an easy journey for you guys to get everything back together, but now that you have you have found yourself in a great position with the band. There is massive interest out there.

RM: Yeah, people know us. We are now established as being some kind of important thing. I am not saying that we agree or necessarily disagree with that, but that is how we are perceived so people pay attention to us, not all the time or anything but enough that we can play.

On the last Mission Of Burma tour we did in December most people knew who we were. We did play in places like Zurich. Now most people in Zurich had not heard of us, so we thought this is going to be the show that bombs. Everything had gone really well and now finally we were going have a bomb, but no… They really, really liked it, and I was selling merch afterwards and this girl came up to me and said, “Where have you guys been all my life?” And she had never heard of us before; how the fuck did that happen? We are just so happy that things like that are happening.

PB: 'Unsound' to my ears is abrasive and caustic sounding, and full of exciting twists and turns. It’s eclectic and yet somehow feels like a single piece of work, a cohesive whole. Do you feel it’s your most complete record?

RM: I think we have made three really good records: ‘Vs’, ‘The Obliterati’ and ‘Unsound’. They are the ones that I really like, but I think ‘Unsound’ to me rivals ‘Vs’ in the amount of variety. I remember when ‘Vs’ came out that some reviewers said that, “It sounds like they are shopping for a style. The first one is like this and the next song is like that”. The thing is we were not looking for an identity. We are just diverse, and I think a lot of that is apparent also on ‘Unsound’.

We have three writers and that helps, but even from the same writer and this is just from my side of the mountain you have got ‘Fell Into The Water’ [‘FellàH20’] which is just a murky but streamlined groove, and then you’ve got ‘ADD In Unison’ which has got psychedelic left turns constantly happening. I think throughout the record there is so much diversity and I personally like diversity. Some people may like something that just has a groove and they can sit through it and it stays the same, but that’s not how my brain works.

PB: The songs on the new record do not at any time seem forced.

RM: I feel that we were more excited about doing this one than our last album, ‘The Sound The Speed The Light’. We were just out of control. We were having a blast and maybe sometimes we made it to the end of the song by the skin of our teeth, but you can feel that excitement and enthusiasm in it. Everything on there is very honest. Someone may say that we are doing too much of this or too much of that and that’s fine. If we are for you, well, we are not doing it on purpose to provoke you. We are doing it because it’s what we like to do.

PB: What about the final song, ‘Opener’? The “Forget what you know” mantra at the end of the song could mean just about anything, but I like to think you mean that the audience can forget what they know about Mission Of Burma, and the next release could jettison you into some unknown territory. Sound about right or am I way off base?

RM: Well(Laughs)… There is a couple of reasons that it is last on the record.

Primarily because it’s called ‘Opener’. That’s just our bad attitude, but by saying “Forget what you know” that came about from when we did ‘The Sound The Speed The Light’ and we all agreed that we were not at the top of our game.

So when we started to make this one I brought in a song and Pete [Prescott, drums -Ed] brought in a song, and they were kind of similar to what we had done before. Then Pete said, “If we are going to do a new record, we have to do something different,” so I threw away my song and he threw away his song. The next one I brought in was ‘FellàH20’ and then ‘This is Hi-Fi’ which is pretty different, and then the whole band did that to some degree,It wasn’t hyper radical, but we tried to get out of our comfort zone and to me that’s where the phrase “Forget what you know” comes from.

We had already done that, so we tried to be innocent again and throw ourselves off a cliff. You never know where you’re going to land. If you are going to try and make sure that you land on a soft pillow, then why the fuck are you making rock music?

PB: And what about writing new material? How do you follow up a record like ‘Unsound’?

RM: Well, I have written two songs so far, and they continue to push the boundaries according to the guys in the band and the people that have seen us play them which is good. Pete has started to bring in one too. Usually we don’t think about making the next record. We just start to bring in songs. and when there is six or seven then we go, "Oh-oh, I think it’s time to make another record."

At this first phase where we are at right now I tend to write the most as anybody who looks through our writing credits sees, not that those songs are the most important or anything but I’m just always writing. At the moment there are no plans to write another record. I believe that we have another really good record in us yet though.

PB: Does Bob Weston ever bring fully formed ideas to the table for the band to work on, or does it always work in the reverse where he is presented the song ideas and adds his parts from there?

RM: So far he hasn’t, you know. He plays in Shellac and he’s got plenty of a life of his own, so, no, he hasn’t brought stuff in. But when we have a song he will add some parts and they will always be things that we wouldn’t necessarily expect, so he alters the material but he doesn’t bring in the core songs, but in the future maybe he will. I don’t know.

PB: He’s been in the band now longer than your original song manipulator Martin Swope ever was. Do you still see him as the new guy?

RM: No (Laughs). Besides he was in the Volcano Suns with Peter years ago and he produced Clint Colney’s band Consonant and he played trumpet on my avant-garde chamber ensembles in the early 90s, so we have all known him for years and so, yeah, he is not the new guy.

PB: Have you kept in touch with Martin at all?

RM: He’s not very communicative. He lives in Hawaii with his family, and he kind of dropped out of the music scene, I think the last time I emailed with him was five or six years ago. I’d be happy to talk to him again, but you know he has his own life and I totally respect that. So I have no idea if he has heard the new record. But if he asked for it I would send it to him. Maybe he’ll see this interview and say, “Wow, Roger said he’ll send me a record”.

PB: There is a lot of footage online from both eras of the band playing live, and it would appear that with the most recent shows you guys are more fired up onstage than you ever were. What drives you?

RM: Who knows? It flies in the face of logic completely. Why when we are in our late fifties and me at 61 does this band push itself so hard? We just played in New York. and my brother Ben who played saxophone in Destroy All Monsters with Ron Asheton, well, he sat in with us, and a friend of ours that watched us, she described it as “Burma has gone completely feral.” It’s as if we are a bunch of wild and dangerous animals on stage (Laughs). Why is that? I don’t know, but it feels really, really good. It’s one of the most satisfying things that I can do with my life is to play a Mission Of Burma show. It’s so cathartic.

PB: Well, I think you wouldn’t do it otherwise.

RM: Yeah, right.

PB: It’s that cathartic release that gets most people into punk rock and hardcore in the first place. Was it the same for you?

RM: Well, I can only speak for myself as the other members will all have something different to say on the subject, but I had a band in 1969 and 1970 which is in fact now reforming called Sproton Layer. We were a very psychedelic band and described as Syd Barrett fronting Cream. It’s with my two brothers, and we are playing gigs this summer and we haven’t played a show for 43 years but…

In 1969 I started my first band. I wrote all the songs with some help from my brothers too, but it was there that I really found my voice and a couple of the songs sound a little like Mission Of Burma actually. Then during 1970 and 1971 rock music had gotten so conservative that by 1973 I had given up on rock. I had no interest in it anymore.

I went to music school, and then when I came back to Michigan after that as if from out of nowhere the first Devo single showed up and Pere Ubu too. Patti Smith’s first record came out and I was like, “What the hell is this?” Then when the Ramones showed up all of a sudden you could do stuff again. It felt like the world allowed for creativity in rock music, and even though by then I was a very skilled musician having been a composition major at music school I loved the Ramones. The Ramones were gods. That’s my opinion, but in some certain respects that should not have happened. They could barely play their instruments, but I found that so much more refreshing than just about anything else.

Because of that I was allowed to become interested in rock music again, and complete what I hadn’t completed at the end of the psychedelic era which is form a band that can actually do something, and that became Mission Of Burma and post-punk and bands like Wire and Television. That was just incredible. ‘No New York’ for instance was just amazing.

PB: If you can remember as far back as 1981, there was that track ‘Outlaw’ on your ‘Signals, Calls and Marches’ EP that I loved so much. Can you tell us a bit about it?

RM: I have a really good memory for this stuff.

Even though ‘Outlaw’ sounds like Gang of Four, for us Gang of Four did not exist at that point in time. It was very much influenced by that ‘No New York’ stuff like the Contortions, but it was also me going back and rediscovering my interest in Sproton Layer with the disjointed and incorrect chord progressions, but it was that twisted funk from that ‘No New York’ stuff that was the inspiration for the groove. That guitar solo to me, however, sounds like Sproton Layer. There is that psychedelic compression and harmonic intervals, and those lyrics are very, very dreamlike.

PB: Yeah, if you take those lyrics out of the context of the song and read them on paper they are pretty trippy.

RM: Yeah, super trippy. As we progressed my lyrics got less trippy. I think I wrote that one before we even got Peter in the band. Me and Clinton had just stared to write stuff and we didn’t really have a band yet, but we thought it was good and thought, “Let’s do this”.

PB: With ‘Vs’, the track ‘Secrets’ really nails down what the band’s core sound is for me? How did that come together?

RM: That was the third or fourth song I wrote for the band, I was very interested in Steve Reich at the time, and he was into gamelan so there was no need for harmonic change. With gamelan music, it is not the harmony. It’s other patterns and things that make the music more interesting. So that is basically a one chord rock song, but it was an ambiguous chord. So that was the idea behind it, I was thinking how can I make something so simple as one chord into complex music and interesting to the ears, and that’s why there is a drum solo instead of a guitar solo. Then I put in all these little variations, so there is kind of a chorus and kind of a bridge, but basically it’s all one chord.

Putting the vocals at the end also appealed to me, and those vocals were totally derived from when Clint used to work as a bartender at a pub called Jacks in the Cambridge, Boston area, and I would sit there drinking for free which was a pretty good deal (Laughs) and watching these people standing around and looking at each other but not knowing what to say to each other, so they were just fidgeting. That’s what that whole song was about - The whole thing of not really communicating, but there is some tension there.

PB: What about ‘New Nails’? It’s so weird but it really stands out for me., It’s my favourite Mission Of Burma song.

RM: The riff itself (sings the riff) was from a description from my brother Darren. He came up with the phrase ‘hand chords’, where you just put your hands on the guitar and try and figure out what’s there. Instead of saying, "Now I am going to play an A chord," you just place your hand down. So I picked up a guitar and my hand was in that exact position, and I just played it to see what it sounded like, and it sounded really cool, and that’s the main riff.

It’s basically just a tirade against organised religion, and in this case Christianity and how perverse it has become. I am very much against organised religion, even though there is a lot of things about Christianity that I believe are good. I would say there are a lot of things that are good about all religions, but once they become organised you lose the spirit completely, and when you lose the spirit of the spirit then you’re totally fucked.

At the end there is like this jaunty little ditty where you have Jesus walking round the desert saying, “Please don’t make an idol of me,” and we have Martin doing those loops and it sounds almost demonic. To me that is one of Martin’s greatest tape loop manipulations. Also I played cornet on that one, and Clint always refers to it as Roman trumpets because it’s all set in this Christian environment. It’s like a call to the gladiators or some shit.

PB: When Clint brought in ‘That’s How I Escaped My Certain Fate’, what ran through your mind? Did you know straight away that that song would be on the record?

RM: There was no record to plan for. We didn’t have a record deal at all at that point. We were just making music. The first thing you do is make music and by the time Mission of Burma recorded ‘Vs’ we had 2 or 3 albums worth of material, so it was just a case of whatever songs came out good made it.

I will say that the first ever song Clint wrote in his life was ‘Peking Spring’. He’d never written a song and then he brought it in fully formed, and I’m not a guy without an ego or anything, and I thought, "They’re my songs and it’s my band," and I had this long tradition of song writing, and then suddenly Clint shows up out of nowhere like Zeus pulling Athena from his eye. This fucking song, honestly, it was devastating for me.

It became a huge radio hit and I thought I was going to be the big hit writer, but very quickly I got over that, and I realised that Clint doing that sort of thing and me doing this sort of thing, and then when Pete starting writing later, that is what makes the band so interesting. Without Clint’s epic rock songs and my avant-garde doodlings and Pete’s rantings, it wouldn’t be nearly as interesting. It’s how they interact, and we perform with each other that makes this band.

I will say though that when Clint brought in ‘That’s When I Reach for My Revolver’ Pete and I stopped and said, “That’s a hit”. This was before we had even gone through the song once. We knew that that was our biggest hit right there.

PB: On a commercial level do you think that any of your other songs deserved equal or higher status than that one?

RM: No not really, it depends on what way you look at it, but ‘Academy Fight Song’ and ‘Reach for My Revolver’ are the two biggest. There is a reason that they’re big. They each have a real hooky chorus and they are easy to sing along to. Clint has a stronger pop sensibility than Pete or I. ‘…Certain Fate’ is good too, but it’s just not quite as gigantic.

PB: Where you surprised at how well Mission Of Burma was represented in the book ‘Our Band Could Be Your Life’?

RM: It’s quite possible that it was one of those moments where I broke down into tears if you want to know the truth. Of all the bands that are in that, book we are the least known. I mean, we are nobody. The Minutemen put out a lot of records and they toured a lot. We didn’t hardly do anything. We put out one record and an EP, and then we disappeared. I mean Black Flag, Sonic Youth, Butthole Surfers and the Replacements, these groups were all big. We sold less records than any other band in that book, and we considered all these people to be our peers. We never, however, expected anyone else to think of them as our peers, so literally when I read that I cried. There was a release that somebody had finally put us where I always thought we belonged, but dared not think that I should be there.

If you have seen the documentary that’s out there, then you already know this, but what was really weird was that when that book came out we reformed about half a year later and we didn’t intend to. Somebody asked us to play some shows. We were so stunned to be in a place that we thought we actually should be and never expected to be that to us it was unbelievable that after all these years somebody else actually thought that too. People started paying more attention, and somebody said you should play this show, this benefit and I said, “No, we are not going to.” Instead we did something else, and now here we are still playing. It’s really weird how things work out.

PB: Along with the book, the advent of the internet and downloading, both legal and illegal would have brought your music to an entire new audience. How does that make you feel?

RM: Personally, I would rather there was no illegal downloading. When we released ‘The Obliterati’ compared to ‘ONoffON’ two years earlier, it sold half as many records, but it was the equivalent of selling just as many because sales are down everywhere. It makes it more difficult for the artist to survive, but I’m not going to wail against it because it’s what people do. It’s the new norm. It’s unfortunate for Mission Of Burma because if we made more royalties we would be able to record a new record sooner. Soon enough it will settle out. and I think there will be a new paradigm in its place.

PB: Getting the band back together and being such a noisy act, you must have had concerns about your on-going problems with tinnitus.

RM: In all honesty. we thought we were only going to play two shows, one show in New York and one show in Boston, and that was going to be it. Then it turned into three shows in Boston and two shows in New York, all sold out. Shellac wanted us to go to England to play ATP and we had never played in England, so we thought, "We’ll just do that," which of course turned into "And then we’ll do that and that." We don’t play so much though that it is a massive concern for me. Back in the day Burma rehearsed two or three times a week and played twelve shows a month. It’s a very different world that I am living in now with Burma. We rehearse much less and play fewer shows.

Still, it is a concern and we have a Plexiglas thing round the drum kit, and I don’t use any monitors, and my amp is at the side of me instead of blasting in my ears. I don’t use those headphones anymore, but I have these really, really strong walls of rubber that I put into my ears. They go in really well, and they don’t come out when I am running around and yelling and screaming and shit.

PB: If ever there was an iconic silhouette in punk rock, then it would be you playing live holding your guitar with those huge ear mufflers on.

RM: That’s a good one (Laughs). The reason I don’t wear them anymore is because they finally figured out a material that feels a bit like silly putty, and when you put it in your ear it doesn’t work its way out. Plus also it sure would be nice to see a picture of me playing a guitar without those things on, and now I can afford to do it.

PB: What about the artwork on your albums? The recent ones have seemed a little thrown together whereas ‘Vs’ for instance is a beautiful piece of artwork that wouldn’t look out of place on a wall.

RM: A time when we were really involved with it would have been with ‘Vs’ and ‘Signals, Calls and Marches’. We had an artist called Holly Anderson who helped write lyrics to some of Clint’s songs. Well, we were working with her, and we spent a lot of time on those covers. Those are pretty iconic.

The ones since then…

PB: Until ‘Unsound’, they have been a little bland.

RM: I thought so, yes. ‘The Obliterati’ cover for instance is just a picture I took on an aeroplane of clouds; it’s completely bland and kind of smooth, completely contrary to what the music is. We just couldn’t decide, and we rehearse so rarely we just think, “Yeah, that’s good enough.” But in the case of ‘Unsound’ John Foster, a graphic designer who works at Fire Records, he said, “Well, I’ll do it.” So it was the first time that it was out of our hands, and I believe that is partly as to why it came out better. He was sending us stuff and it went back and forth a lot, so we steered him. I think, however, that is one of the best record covers that we have had since we reformed.

PB: Finally, back in 2008 Peter said in an interview that due to the ferocity in the way that Mission of Burma plays live that he gave the band a two year life span from that date. What happened?

RM: Well I jump around all over the place. We did a Volcano Suns song in our set last week, and after we listened to the original Pete goes, “Wow man, that’s really fast”. He can’t really play as fast as he used to. It used to be just sheer madness. But I actually think that’s good for Mission Of Burma because some of those early recordings of us playing sets in, say, 1981 have us playing the songs so fast when some of those songs are so complex that it was no wonder that people didn’t know what the fuck we were doing, and now we are forced to play them a little slower it’s just that little bit easier to hear what those songs are about.

But some of the shows this year have been the best we have ever had. It was 2008 that he said that, and now it is 2013 and we are still rocking. Perhaps our age is working to our advantage.

PB: Thank you.

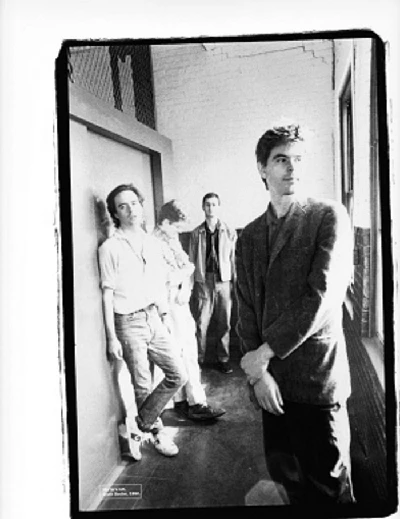

Picture Gallery:-