published: 23 /

4 /

2011

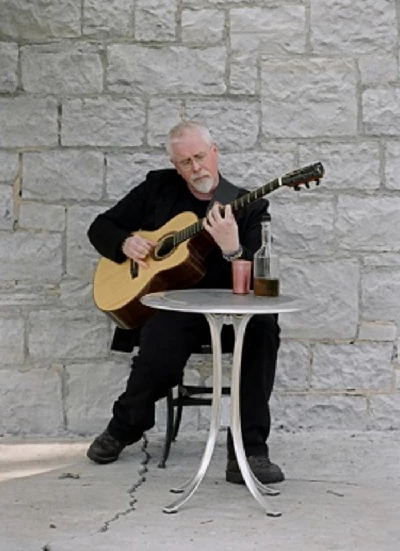

Lisa Torem speaks to Canadian singer-songwriter and activist Bruce Cockburn about his forty year songwriting career, politics and his just released 31st album, 'Small Source of Comfort'

Article

I didn’t actually think this interview would ever come about. The first time that it could have happened Canadian singer-songwriter and activist Bruce Cockburn rambled through the US to promote his 31st album, ‘Small Source of Comfort’, and his vehicle broke down, somewhere in the desert, forcing him to return home prematurely.

The second time I would be at the airport waiting for a plane that actually never took off (but, of course, it was too late to reschedule), but, as they say. “three’s the charm” and our long-awaited conversation finally took place.

Before going solo, Cockburn performed with 3’s a Crowd with David Wiffen, Colleen Paterson and Richard Patterson. Then, as a solo act, Cockburn headlined the Mariposa Folk Fest in 1969 when Neil Young cancelled to attend Woodstock.

His lyrics have included Biblical references, intense political observations and environmental concerns. In 1979 the single ‘Wondering Where the Lions Are (“Dancing in the Dragon’s Jaws)’ propelled his US career.

In 1984 Cockburn’s ‘If I Had a Rocket Launcher’ from his ‘Stealing Fire’ album, which was about his reactions to Guatemalan military helicopter attacks, further established him as a songwriter/humanitarian. His concern about land mines, the International Monetary Fund and the inequities and triumphs experienced by indigenous people in third world countries continue to inspire his lyrics and attendance at charitable events.

In 2008 Cockburn performed with Canadian senator/retired general Romeo Dallaire at the University of Victoria to raise awareness and funds for child soldiers. In 2009 he travelled to Afghanistan to play for Canadian troops and was given an actual rocket launcher.

Cockburn’s travels have also sparked a great interest in world music. In Mali in 1998 he performed with Ali Farka Toure and kora master Toumani Diabate, an event which was chronicled in filmmaker Robert Lang’s documentary, ‘River of Sand’.

Cockburn’s extensive repertoire has been widely-covered by Barenaked Ladies, Judy Collins, Anne Murray, Ani DiFranco, Dan Fogelberg Tom Rush, the Jerry Garcia Band, kd Lang. Canadian singer songwriter Steve Bell on ‘My Dinner with Bruce’ and jazz guitarist Michael Occhipinti have recorded tribute albums in honour of his legacy.

In addition Cockburn has been a recipient of the Juno Awards, was inducted into the Canadian Music Hall of Fame and was made a Member of the Order of Canada in 1982; then promoted to officer in 2002.

Over the course of our conversation, however, as Cockburn revisits previous works and makes observations about his current projects, he strikes me, essentially, as a humanist, still committed to, hopefully, moving his audience with well-crafted, meaningful lyrics and technically-proficient, engrossing performances. On the soaring wings of his 2011 American tour, Cockburn reflects back.

PB: How did the collaborations on ‘Small Source of Comfort’ come about?

BC: Gary (Craig, percussionist) and I have worked a lot together before. He was an old friend and musical cohort of Colin Lindens and he’s played on my albums before and he’s toured with me before, and we were also in a trio together.

That was a really great experience, a musical group that was underground. This music didn’t seem to want keyboards as much, and, in the meantime, I’d gotten acquainted with the songwriter Jenny Scheinman in Brooklyn.

My girlfriend was living there and I was spending a lot of time in Brooklyn and we ended up crossing paths a few times with Jenny, and she invited me to play at a couple of her little gigs, which we did as a duo, and it was kind of a major step. So one thing led to another. I really have a high regard for her, both personally and musically, so I was really happy that she was able to join me for this album and also tour.

PB: The new album has five instrumentals and you had written ‘Lois on the Autobahn’ for your mother. I’m wondering why you chose to write an instrumental, rather than something lyrical, in her honour.

BC: For me instrumental pieces aren’t really about anything. They usually spring out of something that I’m exploring on the guitar, and ‘Lois on the Autobahn’ was no exception. They all have to have titles (Laughs). You’ve got these pieces, you have got to call them something, so, what does this remind me of, and it happened that when we recorded that piece it didn’t have a title yet. But everybody who heard it said it reminded them of driving.

PB: Do you block out certain instrumental parts or choose tempos before you start creating an instrumental or do you rely on your intuition as you go along?

BC: It’s a question of following a trail, sort of. It is probably closer to the latter, but I’ll get an idea that sounds like it could go somewhere and just play with it, wrestle with it, whatever, until it’s going somewhere. So, it’s a conscious delivery in that sense, but the individual ideas may come from fooling around and stumbling on to something. But it’s a question of taking the elements that exist and then deciding do I need something else, and, if so, what is that, and looking for something that will make a pleasing entity for people to hear.

‘Lois on the Autobahn’ is actually played on the baritone guitar and I think I wrote it on the baritone. In fact I’m sure I did and it was a case of stumbling on the very first riff, and then finding the elements that would work with that. And, once it was done, I recorded it, and everyone was happy with it, and, like I said, when I heard it come back at them, everyone, including me, felt that it just felt like the road; the highway going somewhere….So, I wanted to get that idea in the title, since it seemed to be there, anyway. My mother had died in August last year, in between the recording and the creating of the credits for the album, so I thought I’d put her in there too.

PB:’Call Me Rose’ is an unusual theme. How did that come to you?

.

BC: (Laughs). I wish I had a better answer for that. I woke up one morning and there it was.

PB: Was it part of a dream?

BC: I don’t think so. That’s the obvious thought. But I don’t think so. I don’t remember having dreamt it. It was right there, almost completely written in my head. And, my theory is my head was full of Richard Nixon, because there was a PR campaign, around that time, about five or six years ago, during the Bush administration and they seemed to be promoting the rehabilitation of Richard Nixon’s image.

You’d turn on the radio and the TV and read the newspaper and there was some pundit telling you that Nixon was grossly misunderstood, and that he was the greatest president ever and the wonderful thing about that was that it lasted maybe a month or two, and then it abruptly stopped, and what it seemed like was that somebody had spent money on a campaign like this and decided it didn’t work and when the money ran out they stopped (Laughs). And the wonderful thing is it didn’t work.

The people didn’t buy it. The people who said, our president, right or wrong, at the time, are still alive and probably still feel that way, but most people who remember Nixon remember him for the sleazebag that he was.

So this stuff was rolling around in my head, and I was just thinking, maybe, what would the actual Richard Nixon look like, and this fantasy appeared of him having being reincarnated as a poor, single mom and still having some lessons to learn.

But he’s accepted the offer of redemption. He just has to pay his dues now.

PB: Has being a celebrity or, maybe I should say, a well-known figure been a benefit as far as getting your messages across or a hindrance?

BC: Well, I don’t know if I’m much of a celebrity…

PB: You’re travelling and you’re touring, as opposed to someone doing a 9-5 factory job. Do you think that gives license to people to say, “I would do that, too, if I were an entertainer?” Do you feel you’re in a spot where you can really influence people?

BC: I don’t think much about influencing people. Of course, like everyone else, I’m attached to my opinions and I like to share them with people, and it feels better when they agree with me.

But, really, I feel what I’m doing with the songs is taking life as I understand it and distilling it in little bits and pieces into a communicable form, and hopefully people will find something there that resonates with them.

If I can persuade someone to take a second look at something that they may not be looking at or to just approach some fact of life from a different angle, it’s a good thing, but you can’t bank on that. It’s not about trying to persuade people so much, but I think the sharing of experience is valuable, and, because I don’t have a 9 to 5 job, like you said, I get to travel around, I get to experience things that are different than what most people get to experience.

PB: You worked on a documentary, ‘Return to Nepal’. You took a personal look at two brothers, who became farmers with little in the way of resources. What did you come away with from that project?

BC: I was in Nepal with a Canadian Government Agency and it was the second time I had been there, so we called it ‘Return to Nepal’ as I had taken a similar trip five years earlier. The original idea was to go back in twenty years and see what had happened, in the intervening time, but we ended up going to different places and didn’t return.

But it wasn’t what I set out to be part of. But those guys were amazing, those two brothers. Incredible. People who think that third world poverty is a result of laziness - you need to see things like that because there is a tendency to sit in comfortable surroundings and think, “Why don’t they just work harder?”, and I know that I run into that sentiment, here and there.

PB Sometimes people make those comments to mask their own apathy or guilt.

BC: Sometimes it is exactly that. There’s people in the third world, just like in the other world, who are lazy. But, most people have to work so hard just to survive. Really there’s no opportunity for them to put away money. Most of them are in terrible debt. That’s sort of the colour of poverty.

You can find that same kind of poverty in inner-city America, but it’s in a different context. There’s a lot of emotional baggage around between rich and poor people, that must exist elsewhere too, but there’s a different kind of chemistry that exists between us and the third-world citizens. Really whose poverty allows us to live the way we do? There’s a real cause and effect there.

It’s hard to point it out in any one instance. Poverty is often the result of a mutation by us. And, of course, the film is a different way to get that information out there rather than by songs. But it was nice to be a part of that.

PB: Let’s talk about what might be a very personal song, ‘Pacing the Cage’, and it lyrics of “Sunset is an angel weeping/Holding out a bloody sword.” That’s a gorgeous line. Do you still feel the power of those lyrics when you perform it?

BC: Yeah. It’s still depressing. (Laughs).

PB: Does it feel good to get those depressing thoughts out in that form? Does it help you in some way?

BC: It does, yeah. It helps me to share it and I think other people will relate to it. I’m not sure how it hits young people, but anybody over 50, and possibly a lot of other people too, experienced that sense of futility of being stuck somewhere. You don’t feel like you’re moving anywhere. It passes.

Enough people relate to it that I think that condition is pretty widespread. When I sing it on stage, we’re all sharing that. That’s the beauty of live performances for me. I guess it’s subtly different depending on the kind of music you’re doing, but my music is so lyric oriented and the audience come knowing that and they respond to the lyrics in there…so the songs become a vehicle for us all to sit in that room together and share a feeling. That to me is precious.

PB: What about the song ‘Gifts’? Was that meant to convey a different mood?

BC: Well, it’s an old, naïve song from when I was young. Back then, if I use the word ‘committed’ it sounds more deliberate than it really is, but when I write songs I write lyrics and then I write music to go with the lyrics.

But, in the early days like that, it wasn’t so much of a commitment. It was more of a back and forth. Anyway I discovered that that would be a song and not an instrumental piece. So I wrote a verse to go with it and I liked the fact that it was just one verse, and I used it to close shows back in the early 60s and 70s. So, I came up with this sentiment again about sharing. I guess maybe it was the first time I’d said it in a song. Here we are, the entertainers, the musicians, whatever, here are the gifts that we are trying to use to the best of our abilities. It’s just kind of a gesture of thanks or a statement of thanks, the fact that we’re all able to share these things. As I’ve said, it’s kind of naïve. I wouldn’t write the words exactly that way now.

But it really works. It sat there for so many decades, without me recording it or performing it for that matter. I remembered the song. I never forgot about it. But I had told my manager, Bernie Finklestein, who is also the founder of my label True North Records, that I could save that song for the last album because he was suggesting it for the first album and I just kind of flipped it, and said, “Oh no, I’m saving it for the last album.”

I’m not assuming this album is my last album. It seemed like it was time to put it out there just in case.

PB: You’re working on your memoirs and you’ve been approached by publishers before, so why did you decide that now is the right time?

BC: In the past when I’ve been approached it was by people wanting to write my biography, and it always felt to me like it was something that I should do myself.

And, it also felt too soon, premature to be forty-years-old and have a biography. Just old guys are supposed to have biographies.

PB: Didn’t Justin Bieber just write his memoirs?

BC: Exactly. I was at a book store one day and there was the life story of Avril Lavigne. She’s probably 19. It’s foolish. It’s just marketing. That’s all it is.

But I don’t want to be part of that kind of thing. I’d always say no, but I was approached by Harper Collins. This time it seemed like maybe it was the time to say yes.

It was a good offer. I could write it myself, and etc., etc., Just seemed like, okay, let’s go.

I’m wrestling with myself a lot over it though.

PB: Why is that?

BC: I don’t know. It’s a struggle all the way. I don’t want to tell all this stuff about myself. My early childhood and all of those things are so distant. It’s interesting, those bits of childhood stuff, but you start getting into the adult world where things are more complicated and you’re dealing with the feelings of people who are still alive, and I’m not sure how best to tell the truth without making people miserable (Laughs) and I have no desire to do that.

But anyway that’s the kind of thing that I’ve been struggling with. I don’t know. Maybe the songs should retain whatever mystery they have for people. Maybe it’s not good to tell all about me. But, on the other hand, there’s a nice ego stroke in thinking that they will, so that’s what’s going on.

PB: A lot of your original music has been covered by female artists, and that’s not always the case for male singer-songwriters.

BC: I never thought about it actually, but I like the idea.

PB: Because some of the songs written by male songwriters, I don’t think, would particularly inspire or feel genuine to female artists.

BC: I think it’s a rather gross generalization, but, to the extent that it’s true that women tend to be more sensitive than men, they’re more aware of their own feelings and they’re more inclined to communicate those feelings or to be communicated with. That makes sense, I guess. But that is an awfully sweeping generalisation.

Maria Muldaur did a wonderful version of ‘Southland of the Heart’, and she had to change a line that she couldn’t see herself singing. She had a very strong reason for that that she wasn’t going to divulge. She came up with an alternate line that was fine with me, but, other than that, it was a very respectful version of my song.

Then there’s Jimmy Buffett, who has recorded five or six of my songs also very respectfully. When he did ‘Wondering where the Lions Are’ he left some of the verses out. That is because he did it for the film, ‘Hoot’, that he made. What I look for in a cover is that sense of respect, and it doesn’t have to be note for note accurate.

One of my favorite renderings of my music by somebody else is a jazz album that Michael Occhipinti (‘Creative Dream: The Songs of Bruce Cockburn’, True North Records, 2001) did some years back, where he completely deconstructed the songs using the instrumental versions.

It’s really creative and interesting, and fun to listen to for me. That is also a way of respecting the material. Sometimes people do it their own way so much, that they might as well have written their own song. (Occhipinti arranged lyric-driven Cockburn songs, such as: ‘Lovers in a Dangerous Time’, ‘If I Had a Rocket Launcher,’ and ‘Pacing the Cage’-LT.)

PB: How does the process work? Does the artist have to obtain your permission to do a cover or are you at their mercy?

BC: Maria was nice enough to ask permission to use the piece. She asked me if I would write a new line myself, and then it would be totally legit. But, that’s rare – that someone would be so concerned with my feelings.

But, most of the time, when you cover a song, we all do it, if I do a Bob Dylan song, it’s not going to sound like Bob Dylan, but I would still try to make sure I got the words right. I guess everybody does that in their own way, but I had a group that entirely changed the music. I still got paid, as the writer of the song, but in their way of arranging it, it came out with my words.

PB: People who grow up with the original version of the song generally really appreciate it, and the people who grow up with the cover version are sometimes surprised to hear the original.

BC: I’m grateful when people want to do the songs and it’s not up to me how they do them. They have to do what they have to do. That’s what it is to be an artist.

PB: If it was the last night of the world what would you like to be doing?

BC: I’d like to be thinking.

PB: Thinking?

BC: (Laughs). Yeah, I’d like to be very aware of what’s going on. In fact I’d probably be drinking wine. That was Sam Phillip’s image. I was carrying a shoulder bag and walking around and she said, “What have you got in that bag?” And I said, “It’s everything I need for the apocalypse, a rope and a knife and my notebooks, and whatever else.” And she just looked at me and said, “So, what do you need for the Apocalypse besides champagne and a couple of glasses?” and I thought how right on that was, so after a time when it hadn’t turned up in a song of hers I used it myself. (Laughs).

PB: So, this is your 31st album. Did you ever think you would continue to be so prolific?

BC: I never thought about it honestly. I never had any long-range plans. But you set things in motion and you never really know where they’re going to go, and years later where they’re still going.

PB: What should people expect in the upcoming American tour?

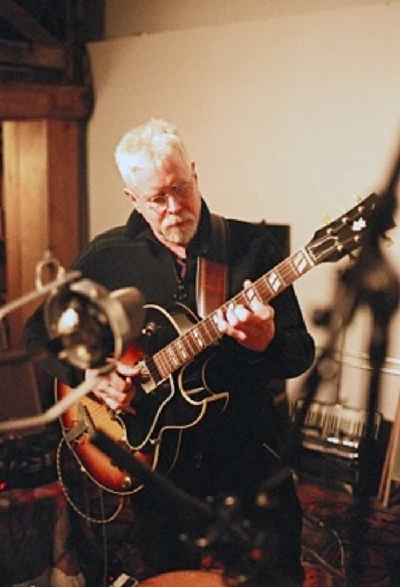

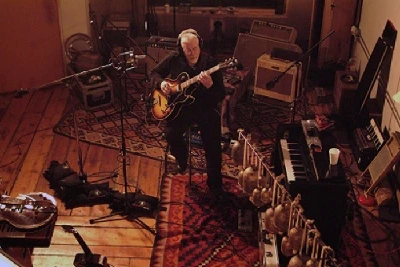

BC: They’ll hear the trio with Gary and Jenny. It’s pretty energetic. It’s a bit more in your face than what I usually do. It’s acoustic. There’s only one electric guitar that I use sometimes in the show. A third of any given show is devoted to the new album, and then we do a cross-section of older stuff. We actually have enough songs in our repertoire to do two completely different shows.

PB: I know you have collaborated with a range of artist including T-Bone Burnett (Bruce collaborated with T-Bone on ‘Nothing but a Burning Light’ and ‘Dart to the Heart’-LT). What have been the most dynamic?

BC: The collaboration with T-Bone was very fruitful. The first time around was really fun. The second time around there was more difficulty What stands out? Right now, I’m feeling the new ones, the fresh ones with Annabelle Chvostek (singer-songwriter from Montreal, who co-wrote ‘Driving Away’ on ‘Small Source of Comfort’-LT) or Jenny.

The creative stuff flowing around there that I’m feeling rubs off on me in a good way. The 31st album - so there’s roughly 300 songs out there. Over the years those 300 songs say most of what I have to say. There’s always room for new things and there’s certainly the possibility of finding new ways to say the old things.

But it gets harder as time goes on to come up with something interesting that you haven’t already done. So, now at this point, I guess it’s like the same reasons for writing the book. It feels good to work with other people and have some input from elsewhere. The result is that the sum is greater than the parts.

That’s been fun, and I don’t have plans, one way or another, to do more of that but, in the past, I’ve got to work with some really great people. Gene Eugene Martynec worked on my first ten albums. He was wonderful to work with and after ten albums I said, “Let’s try something else now.” Colin Linden has produced the last few. Another wonderful thing was that Jonathan Goldsmith produced a couple of albums for me in the 1980s, ‘Stealing Fire’ in 1984 and ‘Big Circumstance’ in 1988. And, he has this great ability to write for strings. This album, again, is something different. It’s funkier.

PB: Colin used a resonator guitar. I love that hollow, old-timey sound.

BC: A resonator guitar is what people call a “dobro.” He’s a master player of it. It’s used in odd ways on the record. ‘Five Fifty-One’, where he’s almost playing a slide trombone part, almost worked like a bass part. We had fun on overdubs.

There’s actually not too many of them. There’s accordion and my friend Celia, who sang, added bits and pieces here and there. Most of what you hear is what came out live out of the studio.

PB: Thank you.

Band Links:-

https://en-gb.facebook.com/officialbru

http://brucecockburn.com/

Picture Gallery:-