published: 6 /

9 /

2010

At a solo gig in London, former Felice Brothers member Simone Felice talks about his recovery from life-threatening heart surgery, other career as a novelist and his group the Duke and the King's forthcoming second album

Article

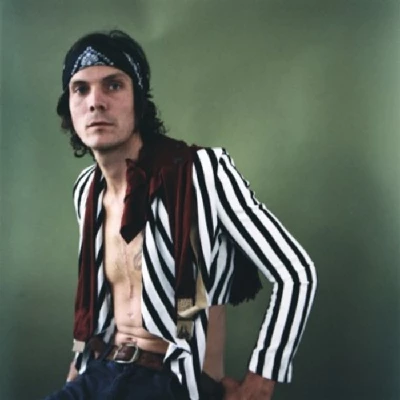

Three months to the day before his show at the Old St Pancras Church in London on September 3rd, Simone Felice was fighting for his life on an operating table in America. That he is here at all is a minor miracle; that he looks obviously healthier than before is hard to believe.

Speaking just before his solo show, the lead singer of the acclaimed Duke and the King sits with his shirt open, proudly revealing a livid scar running eight inches down the centre of his chest. “I’m feeling really good. Like a new man. I had been living off 12 per cent of the oxygen I should have had. People say I look healthier and am glowing.”

This solo gig is his first in London since the operation and comes a few weeks before the release of the new Duke and the King album, 'Long Live the Duke and the King',which is already receiving admiring reviews. With larger gigs to come, Simone (pronounced plain Simon, I thankfully discovered a couple of minutes before meeting him) appears to have been growing in stature as a writer since he left the Felice Brothers to form the Duke and King with a breathtaking debut, 'Nothing Gold Can Stay'.

Simone in many ways, however, came to music, or professional music, relatively late. Now 33, he was writing poems, while also striving to be a musician, and prose a long time before the Felice Brothers had recorded: “I started out when I was a kid, banging about in the garage, playing in a punk band. We played afternoons at CBGBs. But all the time it was about getting the poetry out. When I was 21 I used to travel to poetry meetings and came to love it. That was before I knew how to play music or sing. It began with that and I learnt how to write prose and stories and this has been brought into the Felice Brothers and also the Duke and the King.”

Simone has two books under his belt, both pre-dating the Felice Brothers. 'Goodbye Amelia' is a novella and series of poems and short stories, 'Hail Mary, Full of Holes', a full novel. Both are a rough ride, full of people from the wrong side of the tracks, doing each other serious harm. He is pleased that I have read them: “Wow! They were kind of underground.” His next, less subterranean he hopes, is 'Black Jesus', due out next year. It features an Iraq war veteran returned home.

The Iraq and Afghanistan wars feature largely in Felice’s work, either subtly or more overtly, as in the stand-out track on 'Nothing Gold Can Stay'; 'One More American Song'. This pre-occupation is unusual and not something that is going to enamour him with mainstream American.

“I’m a haunted person,” says Simone, a tall, gaunt man with a piercing angular face. “I have a lot of hope in my heart but I am haunted. I was born the year after Vietnam ended so I’m haunted by the moments of my life when I became aware of this world. Things like my dad’s friends with their legs blown off in Vietnam, listening to Jimi Hendrix: those are my main memories. So war has always haunted me.” Nearly everything he says seems to be with a heavy heart as if he is carrying the weight of the world.

The interest is more than superficial: “I read extensively, I study military history. I just read an 800 page definitive account of the Korean War, that’s how much of a low rent scholar I am! It’s important to know that people are really suffering on this planet. It helps me get through the day and not get bogged down by the little trivial shit we deal with.”

Like 'Black Jesus', 'One More American Song' featured a veteran who “got fucked up over there.” This focus on the survivors, rather than cold casualty figures, stands out. “They get forgotten. The government doesn’t look after them and they leave them to beg on the street,” he says. The parallels between his parents' 60's experience and that of his own are neither lost, nor exaggerated. “My friends are going over to Iraq now and coming back shaky.” This is a reference to new album’s first single, 'Shaky', which opens with the understated “Baghdad, she’s a mean old town.” And, rather than being a dirge to doomed youth, it finds a connection with having your nerves shot to pieces and dancing your ass off.

This goes to the heart of Felice’s message, or lack of it. “I’m not a protest singer, I try to just observe what I see is the American experience, I don’t want to tell anyone what to do or how to live but I want to just show what I’ve seen through my eyes from when I’ve been a little kid until now; the shit I’ve seen on this horrifying and beautiful planet.” The music then does not seek to prosthelytize, and the mood, even in the darkest songs, is positive: “I try to get a great big balance, try to live in that borderline where there’s night and day, rainy and sunny, hurt and pain, love, I’d be bored if it was just one or the other.”

He feels only sympathy and sorrow towards those who join up: “People do what they have got to do, they are on their own journey in life and I try not influence people’s journeys. It’s easy to join, especially when you’re poor and you want to go to college. That’s how they get you.”

Combining rock music and serious writing is not something that is often achieved. The fact that Simone’s written work largely pre-dates his time as a professional musician is highly unusual. Richmond Fontaine’s Willy Vlautin has produced a body of novels which cross fertilise with his band’s output and portray lives from a similar demimonde to Felice. “He’s really cool. We both write about the dispossessed, the forgotten people.”

While prose and poetry is an art form where he has total control, music is by its nature more collaborative: “Generally I am song writer, I write by myself in that lonely place. But with my brothers we did a lot of writing together and with the new Duke and the King album there’s a lot of collaboration. I write them alone, but in the studio we try to bring them to life beyond a raw essence.”

The practicalities of combining something as solitary as writing novels and the cacophony and hectic circus of rock, have been hard to reconcile. “The first books I wrote before the Felice Brothers I was in a really secluded place, a really quiet time of my life. That’s essential, that silence, so whatever the voice it is that speaks to you, or through you, can whisper to you.” He is learning to find this within the disruption music brings to life: “I try to get nice breaks during touring ad recording. I get inspired on the road and try to get peaceful time and go to parks and write there.”

Much has been made of Felice and brothers’ Woodstock heritage, the brothers' in particular being a latter day incarnation of “Weird Old America” brought to life by Dylan and The Band in the legendary basement near their home. There is of course another heritage to the area that pre-dates the Basement Tapes or the festival: “In the Catskill mountains there is a real literary history. A hundred years before the festival, they were writing up there. Whitman wrote Leaves of Grass there.” Felice is inspired as much by literary heritage as rock; the Duke and the King and the Felice Brother’s last album, 'Yonder is the Clock', both take their names from Mark Twain.

To Simone, his output, while perhaps appealing to differing audience, is a whole: “Before I could ever write a poem I was jumping up and down on the stage and banging my head. Both mediums are inside of me and I’m at the height of whatever I’ve been doing with my life and people are paying attention to me. Some people are going to pay attention to the music on the radio and some to the books, its all a matter of taste. There is a loose mythology going through the books, the Felice Brother and the Duke and the King. The same strange light is coming through the trees in all of it.”

Picture Gallery:-