published: 13 /

2 /

2010

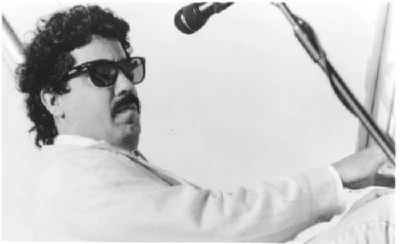

Blues-pianist Barrelhouse Chuck speaks to Lisa Torem about his mentors on the Chicago blues-scene, his isnpirations and plans for the future

Article

After meeting the friendly and enthusiastic Barrelhouse Chuck, first, at a New Orleans- style swanky club on Chicago’s north-side with the Nick Moss Band, and then, a year later, at Buddy Guy’s ‘Legends Nightclub’ downtown, alongside Kim Wilson, I was entranced by the sheer speed of his fingers jack-knifing between piano and Hammond B3 and his confidence, sharing the stage with rapid-fire guitarists and harp players. Even as guest artists got invited onstage randomly, keys shifted, and set lists unexpectedly expanded, Barrelhouse Chuck remained cool, energetic and wildly innovative.

His prized professionalism has found him: performing at the Washington D.C. Inauguration Ball for then President- Elect Barack Obama, becoming a major player in the making of the ‘Cadillac Records’ soundtrack with Beyonce, Kim Wilson and Billy Flynn; up for Grammy 2010, and being the only Chicago blues pianist to have studied with Pinetop Perkins, Blind John Davis, Detroit Junior, Sunnyland Slim and Little Brother Montgomery.

“Chuck, you got that Chess sound,” said Bo Diddley. “Oh man, Chuckie can play…he plays all my stuff, all of everybody else’s, and then some of his own!” said Pinetop Perkins. “He is the best youngster at playing Chicago style blues,” said Little Brother Montgomery. Here are just a few comments, among many more, made about Barrelhouse Chuck’s performances.

But beyond the technical accolades, lies another dimension. Barrelhouse Chuck (AKA Chuck Goering), for more than three decades, was surrounded by a unique family of artists that, not only took him in when hunger struck, and sated his thirst for artistic excellence, but, undeniably, made him an honourary son. Bottles of wine, house keys and car rides were shared freely by all. This was a time when male bonding meant looking a man straight in the eye and watching his fingers speed smoothly along the ivories, octave to octave; when acoustic pianos frequently graced neighborhood haunts.

Today, there may be fewer venues, but brilliant blues- licks still drive –through the hands of Barrelhouse Chuck, a man who is committed to keeping such rich artistry alive.

Barrelhouse Chuck speaks to Pennyblackmusic about his mentors in the Chicago-blues community, his inspirations, contributions to ‘Cadillac Records’ and plans for the future.

PB: In 1979, you drove 24 hours non-stop, from Florida, with your friend Frank Bandy to see piano player Sunnyland Slim at a Chicago’s ‘Blues on Halsted’ and you instantly became friends. Slim taught you piano for 16 years. Why was this friendship so important to you and what was the process Slim used to teach you piano?

BC: Sunnyland Slim helped just about anyone and everyone. I never told him I even played. I followed him around gig to gig. Then he heard me play. Sunnyland said, "Why didn't you tell me you played piano, boy?”

We became very good friends (he would call me his son). I loved him like a grandfather, a teacher, and a legend of the blues. Slim sounded like 1920 on the piano.

Sunnyland would play piano riffs, licks and intros, etc. He would play it slow and show me. I watched the hands of all the old masters while they played the keys.

I took a lick a night for years, listening and watching the hands on the piano. Greats like Blind John Davis, Big Moose Walter, Detroit Junior, Jimmy Walter, Aaron Moore, Henry Gray and Memphis Slim and Erwin.

PB: After studying for years with Slim, how did you manage to develop your own individual style?

BC: I first heard a blues piano player in Gainesville, Florida, named Jim McKaba. He was just the greatest! He played with Little Joe Berson; Jim sat in and played with Muddy Waters. Jim could sound just like Pinetop, Otis Spann, Big Maceo, Memphis Slim. He knocked me out!

So I started to play professionally after playing one month. I would play the piano at gigs and see Jim watching me. Then, Jim would come up and kill me on the piano! Me and Frank and Blind Robert Hunter had a band Red House.

We made $30.00 a night for six months playing every Monday. I brought a real acoustic studio piano to every gig for years in the late 1970s and early 1980s. I hate electric pianos, and still do. If it’s up to electric piano, blues piano will die.

Before Chicago and Sunnyland Slim at 17 years old, I followed Pinetop Perkins around down south with the Muddy Waters Band, town to town. Every night backstage (I was) with my hero Muddy Waters! Pinetop was very kind to me. No one could back a band like Pinetop Perkins did in the 1970s. I loved the way he sounded and sang. Pine showed me lots of riffs on the piano. This all took years of hanging out.

I started out listening to Otis Spann, Leroy Carr, Steve Winwood, Big Macao, Memphis Slim, Pinetop Smith, Big Moose and Detroit Junior (who lived with me for months) and many other blues piano players.

PB: You lived with Little Brother Montgomery and drove him to gigs and doctor appointments. You said he was like a grandfather to you. What was most important about that relationship?

BC: I always asked lots of questions to all of the old timers. Brother played piano for me everyday, eight hours a day, five days a week. His two brothers and his sister would also come by and play piano. Tollie, Joe and Willie Bell Montgomery and Jay McShann would come by and play for Brother and me ‘Confessin the Blues’. That really was great! Brother also cooked me meals when I had no money.

Sunnyland Slim would drop by every Friday at Brothers home. All three of us would drink and play and sing all day long.

LB Montgomery showed me note for note what Leroy Carr played on the piano. LB could cover Stride piano, church, Jazz, Dixieland, standards and boogie. Over 5000 tunes - he could play and sing all the words.

LB Montgomery also gave me lots of advice. He knew music and things to look out for in the music biz. He wanted me to learn more than just the blues. He said, " The blues are the bottom of the barrel. Once you play the blues, they put that stamp on you. You don't go any farther.”

PB: You’ve said that musician Leroy Carr has an unmarked tombstone. That’s sad news for a musician who contributed so much to the culture. Has anything been done about that?

BC: I didn't know that he had a tombstone. So I saved $1500. Took me over a year, and I designed a head stone for Leroy Carr. Then, I found out that a DJ (who took five years to raise the money) put a marker in his grave. I wanted to do this for him so bad! Every night on the bandstand I sing and play his music and tell people listening to me, “Every blues piano player owes a dept to the great Leroy Carr".

PB: You mentioned, in an earlier phone conversation, that the west- side and south- side musicians have a different way of approaching playing- out live. Could you elaborate on that?

BC: Yes. The west-side blues musicians didn’t want you to solo when they were playing, singing or taking solos. But, the south-side blues artists, like Muddy Waters, (they’d be) all playing solos together, but one was leading!

PB: That sounds pretty wild! It’s surprising, to me, that you started out originally playing drums. What made you switch to piano? Do you remember the moment when you decided that this was uniquely your instrument?

BC: I started out playing drums around five or six years old. I would play along to records of Chuck Berry, the Beatles, all 45s of the Motown sound and my favorite band Traffic.

I started listening to the blues at age nine. I didn't really start playing piano till I was 17 years old. When I heard Otis Spann on a Muddy Waters record ‘ You Can't Lose What You Never Had’, I said " I'm going to play piano.”

Otis was just so great, so much feeling, so blue, like nothing I had ever heard before. I bought around 1000 blues L.P.s by the time I was 14. So, I listened to the blues and piano first, before I ever thought about playing the keys. I could tell you who every musician was, by ear, hearing every Chess record that I owned! I just loved the Chicago Blues the most. That's all I ever wanted to play.

There was a piano in my house and my mother played hymns on it. I would walk by it all the time and make- up songs by ear, and copy tunes or parts of tunes that I was listening to at the time. I learned ‘Burning of the Midnight Lamp’, by one of my heroes, Jimi Hendrix, when I was eight years old on the piano. I also listened to Louis Armstong. He was the greatest to me!

PB: You’ve been inspired by some beautiful influences. Let’s get more specific, though. Can you describe the unique styles of boogie-woogie and stride piano, in layman’s terms, and also tell us; are these styles endangered? Will they only be available on recordings or do you believe the style is still being learned and performed by new players coming up?

BC: Boogie woogie piano was based on the blues. Typical boogie woogie bassline you walk your left hand with a 12 or 8 bars. This became very popular in the early 1930s to the late 1940s. Pinetop Smith was the first man to give it the name boogie woogie. He made the first Boogie ‘Pinetop's Boogie’ in 1929 in Chicago.

James P. Johnson was ”The Father of Stride.” Try a listen to him. Little Brother played his style and talked to me about him often. It’s a much different and harder style to learn. Ragtime piano is part of stride.

And are these styles endangered? There are boogie woogie players all over Europe. Some try to play faster than the next and think playing the piano is a competition. But, there are some really great piano players over there that really can play!

I listened to Jimmy Yancey and Pinetop Smith’s boogie playing, first. The reason their guys could play boogie so well was because they were great blues piano players first. Mead Lux Lewis, Albert Ammons and Pete Johnson were really great and played a lot more notes than the other two guys did.

PB: You worked with three other pianists Chicago Blues Piano Masters, Detroit Jr., Pinetop Perkins, and Erwin Helfer, on for your release on Sirens Records; ‘8 Hands on 88 Keys.’ What was the process for showcasing each pianist in a unique way?

BC: First, I want to thank Steven Dolins at Sirens Records for believing in blues piano and for recording all of us.

Pinetop, Detroit, Erwin and I would start playing solo, then the next piano player would join and play four hands. One of us would sing and the other would join him on the piano. We all were good friends. It wasn’t a competition. It was a "fun party.”

I was recording with the masters!! It was great. I met Erwin in Chicago when I was 19 years old. He was playing great Jimmy Yancey, Speckled Red, and boogie piano. He sounded like an old man back then. I liked that he had his own style and wasn’t a record copier. Erwin can play other styles besides blues and boogie. You should hear him play Duke Ellington!

PB: Yeah. Erwin can play those standards so elegantly. Tell me about your originals, say ‘Rooster Blues.’ How do you go about writing an original blues song?

BC: The real title is ‘Blues For Little Brother Montgomery.’

I made this up in the studio as I played it. Pine, Detroit Junior and Erwin were listening as I was recording it. One take, a slow blues in G, with the styles of me playing a little Spann, Little Brother, Big Maceo, Memphis Slim, Leroy Carr and Barrelhouse Chuck.

PB: One take! That’s impressive. How did you get together with Kim Wilson and Nick Moss? And, when soloing, how do you stay out of the way of the other musicians, while also complementing their interpretations?

BC: I called Kim to ask him if he would play on my CD’ Got My Eyes On You.’

(Sirens Records), and his reply was, “I always wanted to record with Barrelhouse Chuck!”

I waited 30 years to play with him and always wanted to play with him! Kim Wilson is the best band-leader and harmonica-player I’ve ever worked with. Man, can he sing, too!

Musicians stay out of each other’s way after they’ve had a lot of experience playing together. You must listen and feel what you’re playing. Musicians like you to play what fits their style.

Nick Moss called me and asked me to record a CD with him Then, we toured together on the road for a year. I really enjoyed making the CD ‘Count Your Blessings’ with Nick and Kate Moss.

PB: How did you end up working on the soundtrack for ‘Cadillac Records?’ Was it challenging to create a soundtrack with present day musicians that paid tribute to icons of another era?

BC: It was through Kim Wilson. He hand-picked each musician for this session for their ability to replicate the sound of the Chess musicians on Chess Records. It was a blast! Marshall Chess was there listening to us record all the tunes he heard being recorded at his dad’s studio 60 years ago.

(Marshall Chess is the son of the late Leonard Chess, the original owner of Chicago’s Chess Record Label-LT)

PB: So, Chuck, did you engage in a lot of research to come up with your arrangements and do you believe the final result was authentic?

BC: They sent us a CD for the songs we had to learn for the session. Also, I had worked with many of the artists who were on the original recordings.

PB: Chuck, you’ve toured all over the world for more than three decades. Where do you think the blues is most well-received? And, why do you think so many great blues musicians still find themselves struggling financially? Do you think this is going to change?

BC: Europe definitely is the most receptive to blues musicians. It’s a mystery to me why we are still struggling in America – maybe because someone is always willing to play for less money. Too many musicians trying to play nowadays? It’s easy for people to think playing music is for “fun” rather than a job. We still make the same money we made back in 1980 at some gigs.

PB: Given your years of clubbing and being mentored by so many great artists; what makes a great blues song?

BC: Exactly the same thing that makes a good story for starters!

PB: Okay, I see what you mean. You’ve opened for Willie Dixon, BB King, Muddy Waters and played with Bo Diddley. What made these icons memorable showmen and how far have their influences spread?

BC: They were master musicians who created a sound that was never heard before. Their influences have spread world-wide, and in all styles of music, whether they know it or not.

PB: Final two questions; what’s next as far as touring, performing and recording? And, what advice would you give to a young performer interested in the blues?

BC: I am going on tour again this year in Switzerland with the Sunnyland Slim Blues Band, in March with Sam Burckhardt, Steve Freund, Bob Stroger, Kenny Smith and Zorra Young.

Then, there will be two tours to Spain. First, I’ll tour again with a great piano player from Spain named Luis Coloma. This will be in July 26- 29. We have recorded and toured in the U.S.and in Europe together a few times! He is the best boogie woogie piano player in Europe.

I just recorded a fine CD with the Cash Box Kings. They are Joe Nosek, Oscar Wilson, Chris Boeqer and Billy Flynn and Kenny Smith. We will tour Spain July 7th-10th.

Then, there will be a California tour in March with the Kim Wilson Blues Review and the dream team! Kim Wilson, Billy Flynn, Larry “The Mole” Taylor, Richard Innes and Rusty Zinn.

In the early spring, I’m doing another CD with Kim Wilson’s band. This will be on Sirens Records with Kim, Billy Flynn, Larry “The Mole” Taylor, Richard Innes, Lorie Bell, and with Buddy Guy on a few cuts!

Aspiring performers and musicians should listen to the original artists. Always listen to the roots of all styles of music. Who made it first; 1920s to the late 1960s, early 1970's for the blues. Anything on Chess Records is the best!

Don't mess up the real blues by playing it “rock blues” or try to re-invent the music.

PB: That sounds like pretty, solid advice. Thank you, Barrelhouse Chuck.

Picture Gallery:-