published: 11 /

1 /

2009

Mark Rowland talks to Jez Kerr, the bassist with Mancurian post punks A Certain Ratio about his group's years on Factory Records from the late 70s to the mid 80s, and the massive influence of New York on their sound

Article

If one thing unites the bands that made up Factory Records' early roster, it was a sense of icy detachment that permeated their music. It is certainly the feeling you get from A Certain Ratio's 'The Choir', an early song of the band's. The song itself is fast and funky, but still has that atmospheric sound that is so familiar from Joy Division's albums.

That sound can possibly be credited to Martin Hannett, the label's official producer, but, although it is that icy sound that initially catches the ear, it's the band's funkiness that really appeals. A Certain Ratio aren't the best known of the Factory label's bands, but their creativity and the part they played in creating modern dance is often overlooked.

The band was formed in 1978 by vocalist Simon Topping, bass player Jez Kerr, guitarist Martin Moscrop and electronics man Peter Terrell. It was a while before the band got a drummer, Donald Johnson.

The band went from playing small gigs in and around Manchester to the verge of stardom on A&M records, before crashing down again in the late eighties. In that time, they mixed punk, electronica, dub, funk, jazz and world music into their sound, pushing their boundaries with each release, with mainly pleasing results.

The band have since started touring again, with the current lineup of Kerr, Moscrop and Johnson and also Tony Quigley and Liam Mullen. They have a new album, 'Mind Made Up', and, although they only play part time now, are playing gigs across 2009.

Jez Kerr talked to Pennyblackmusic about the band's Factory years, and gave such long, detailed and riveting stories that we've divided the stories into sections and let him tell it in his own words.

The Early Years

A Certain Ratio started off playing modest gigs in and around Manchester. The punk ethic gave them the confidence to form the band, but from the off the music was taking from Northern Soul, Kraftwerk, Roxy Music and Wire.

JK : I remember playing at the Russet Club at the Factory in Hulme. It was an early gig and we were playing a song called 'Genotype/Phenotyope', which we used to end our gigs with. It was awful. It was really simple and we couldn't really play at the time anyway. It was a bit monotonous and it wasn't fast. There was all these Teddy boys at the front and one of them leaned over to me and said “play something fast!” 'The Choir' was sort of an answer to that. Punk was fast music. It was all about energy. We quite enjoyed annoying people, playing this dirgy song – it went on for ages as well. It was awful.

When we first got together it was Simon Topping and Peter Terrell who got it started. I saw them play a gig at Pips. I used to go to Pips disco in Manchester, which had about ten rooms. It was a good club. It had like a Roxy Room which played David Bowie and Roxy Music. It had a commercial room which played soul and it had a New Wave room which played Kraftwerk and things like that -it was a great little club. Pete and Simon played a gig there, just the two of them, and I was at the club. I didn't know they were playing. I was in the Roxy Room when these two guys came out and I thought “what the fuck?”.

You know Jilted John ? I lived with Gordon the Moron for about a year. I was there when they wrote the tune. They even asked me to play bass with them on 'Top of the Pops', but I couldn't play it. That's how shit I was. I was a sort of wannabe, but not really a musician. I saw A Certain Ratio play this gig at Pips and was sort of interested in what they were doing, because it was really different. It was just mad what they were doing, but it was interesting and they looked sort of good.

About three months later I met Simon in the street. Him and a girl that I knew at college had become an item and he was waiting for her, so I met up with him. Two days later I played a gig with them. There was three of us for a bit and then Martin, the guitarist, joined and there was four of us for almost a year, without a drummer. We all listened to Northern Soul music and James Brown. For a lot of people then, punk opened things up and made people realise “I could do that.”

We had the outlet of the musicians collective in Manchester, which was funded by the North West Arts. They put a gig on at Band on the Wall every week, so you had a free gig – you didn't have to pay, didn't have to worry about getting people in, so we had a bit of help. That's where we started. A lot of bands started there, Joy Division, the Fall and all that. They all played at that club.

Musically, we couldn't play at all, but we made a noise. We liked bands like Wire. That sort of thing appealed to us. There were a lot of good bands round then that had their own thing. It was an interesting time for people who were into the punk ethic but weren't just into three-chord thrash and we were lucky to get noticed at that point. Factory Records were starting up. They asked us to do a single, and that was it really. We just carried on. There were no contracts or nothing. It was just great that we were making a single. We didn't look any further. We didn't see it as a career. I think a lot of people today who go into it look at it as a career. I think that's the wrong approach.

We'd been playing for about six months. We had a set with no drummer. The bass was basically keeping the rhythm. It was really simple. If you listen to the early stuff, like All Night Party, it's all like that, really monotonous. I remember the barmaids at the Russet Club going “Oh fucking hell, not them again.” We used to delight in the fact that people didn't like us. We'd turn our backs on them. We didn't give a shit about anything, apart from what we were doing, which a lot of the bands then were doing. That's why it was good, because they didn't care, you know. Who gives a shit about what you look like ? With most people now they do give a shit, and that's why it's crap. I'm not really talking about good musicians. I'm talking about young kids, about 16, who can't really play. So if you can't really play, what can you do? Don't try to play. Whereas in contrast they try to play, and they shouldn't. There was a lot of that vibe around then, so we were doing what a lot of other people were doing, and enjoyed what we did.

Going To New York

The band's first single was 'All Night Party/The Thin Boys' which came out on Factory Records. Factory boss Tony Wilson was managing the band. 'The Graveyard and the Ballroom' followed, a compilation of studio demos and live tracks. The band's first full-length album, 'To Each...' was recorded in New Jersey with Martin Hannett at the helm, while the band stayed and played in New York. While out there, playing gigs with bands like ESG and Madonna and watching bands of all types, their eyes were opened to several new genres.

JK : I was quite old. I was 19. Pete and Simon were about 17, 18 and we knew fuck all. The attitude was that no-one's better than you. That's the attitude that gets you far in this industry, though it's no good if you're shit. If you've got something about you, especially as a unit. We looked sort of different, and that sort of fed all of that. People think that we had this big plan, and talked about what we wanted to do, but we never talked to each other. That was better, when you don't have to talk about things. You just do it. That's what Factory was like. When you had to explain something, you were a dick head. It was like be cool and know what's expected, and know what's good. It wasn't something we talked about, but that was the way it was, really.

I can remember at New York airport we got mistaken for some religious sect by these security guys. It's because we always used to wear de-mob suits from Oxfam and shit like that and we had short hair – that was what got them, the short hair. We enjoyed that and the arrogance we had carried us through that. We got a lot of respect from people for that, especially people who didn't know what the fuck they were doing. We were just doing our thing and what ever happened happened. If you try to make things happen it never usually happens. Just do what you do well.

The first time we went there we had percussion and stuff that we were using. We were getting into Brazilian stuff a little bit. We had a flight case nicked at Manchester Airport which had all of our effects pedals and all our percussion in it. When we got to New York, we had to go and buy a bunch of new equipment. We went to New Jersey and the Mayan percussion company that made all the stuff that we used had a store in New Jersey, so we went to the place and walking into that shop was like “fucking hell.” We spent about $5,000 on effects pedals and percussion, not only because of the shop but also the previous night we had seen our first samba band in New York.

There were forty people on the stage and they were all playing drums and cleekers and stuff. It just blew our minds, the energy and the power of these thirty or forty people on that little stage. We bought cleekers, we bought gong baps, we got the load. That was the main thing we got musically, from that samba night.

Also the second time we went we saw Rocky Steady Crew, the first body popping guys. We played a gig at, I think it was called the Roxy or the Ritz. It was about 3,000 capacity, a fairly big gig for New York, and we were headlining. The night before, this lot were on, Grandmaster Flash and all that. They all came from Queens and it was the first night they played in Manhattan, and they fucking took over, man. It blew our heads off. There were loads of people on stage, all these decks, loads of dancing. That was really special, so many people on stage, the dancing, the beat. We'd never seen that before.

It was the same with Madonna when she supported us the first time we played there. We'd never seen anyone come onstage without a band. It was just her and two dancers and a soundtrack. That was new then. We knew she was going to be massive. Especially when she asked us to move our gear and we told her to fuck off. You could tell that she knew what she wanted to do and when we saw the act, it was like, yeah.

New York was like that, I imagine anybody who goes to New York when they were 18 would take in what they saw there. Everything's there, you know. We went there at a really good time. It was the end of the 1970s disco thing. We just caught the end of that. After that it got worse for bands there. It cost more money. There were less places to play, a lot of crack and a lot of police crackdown on crack (laughs). When the town was open and cool, without much danger, we caught the end of that. The subsequent years were still good, but not as good as that first year. We played some odd little places. We played in a lot of cafes, which you wouldn't be able to do now really. Maybe you can now. I've not got my finger on the pulse these days.

We stayed in a loft as well, which was basically a parque floor, white washed walls, a bathroom, and that was it. We bought six mattresses and six sheets and that was where we stayed. It was in amongst all these warehouse buildings, and when we got back to Manchester there were all these buildings that were empty, all these old mills and stuff. We thought “lets buy one of these and make apartments, we'll make loads of money.” We actually looked into it and there was a law stopping you living there, and now look at it. so that was another idea we had.

You can link New York to anything. The clothes we were wearing and stuff, it was a big influence on us. We listened to records there and watched a few jazz musicians while we were out there. It turned us a bit that way, which turned all our fans off us. but we were interested in what we were doing. We weren't interested in becoming famous and making money. We tried that and it was rubbish, but the good things that we did came out of that attitude.

ESG supported us at one gig in New York. The guy who managed them was called Ed Baleman, who ran a record label called 99 Records in Greenwich Village, which was also an independent record store. He managed that band. He had all our records in the store. It was a great little store. He was an independently minded guy, worked his socks off, I don't know if he still manages them, probably still does.

We were recording our first album in New Jersey. We stayed in Tribecka and traveled everyday to New Jersey. We finished the album early. We had three days left in the studio – a crappy little place called Ears Studio in East Orange – and we had these three days, so we gave the studio time to ESG. They recorded with Martin Hannett three really good tunes, one called 'Moody', one called...the really spacey one that I like that I can never remember the name of... 'UFO'. They recorded them there with Martin Hannett. The next time we went over there we played with them in Long Island. Now we're playing with them again, 30 years later, at the Barbican. We'll see who's kept the best.

'Shack Up'

One of A Certain Ratio's most popular early singles was a cover of a Carter and Daniel song, 'Shack Up', which was originally a hit for 70s funk band Banberra. It was recorded for £50 for a Belgian label Crepuscule and released on Factory. It was backed up by 'And Then Again', which was briefly considered as a song for Grace Jones to record.

JK : 'Shack Up' was Simon's idea. Simon was the main instigator of the band, the main lyric writer. He listened to a lot of records and he obviously thought it was a good song. We tried it and thought it sounded great. I think we rehearsed it once before going into the studio to record it. We were going to do the recording in Prestwich at the Graveyard, which was a four track studio. We wanted a single and that was the last track we chose to put on it. It was pretty fresh when we recorded it. A lot of stuff on that record was made up in the studio, which I still think is a great way to do it. It's that live thing, where you make a mistake and that mistake becomes the best bit of the tune. It's always the way.

The Second Album

The band's second full-length, 'Sextet', was recorded in Manchester. For the first time, the band decided not to record with Hannett. Martha Tilson had joined the band by then, and her vocals dominate the record, with Topping moving further towards trumpet and percussion.

JK : We produced that record. We had an engineer there to help us out. He was called...Phil something. I can't remember his second name. We'd worked with Martin Hannett as producer before, and we'd had loads of disagreements with him. Now, I realise he was a genius, but at the time I thought he was an arsehole. I think the most of the musicians that worked with him thought that, but he was unique.

We'd never felt like we'd got our sound, the way we heard it, on to record. Martin got his sound, which I love now, but at the time we weren't keen. It's like New Order. They didn't like what he did to their sound. It's just one of those things. With hindsight, if we'd realised what he was, we could have made it even better, but instead we'd just fight him all the time. Poor guy.

When we did 'Sextet', we were so headstrong, we just said “get us an engineer and we'll do it” It's got something that the others haven't got. It all sort of came together on that album for us really. I think that's why it stands out. The bass sound on the record wasn't much to do with me. I think that was the engineer's work. I remember him telling us he'd recorded with Bob Marley.

We recorded at Revolution Studios in Cheadle Hulme, before it got converted, so it was just a house. It was really weird – downstairs was the recording area and upstairs was the recording studio. It was fantastic. It had this great big fish tank in front of the mixing desk. It was quite an experience. We took it over for two weeks.

That album was one of the most enjoyable for us, because we were more involved in the recording of it and what went down onto tape. Whereas with Martin it was like “fuck off, get out the studio, we don't want you round, could you just shut up?” I think that's why you get that good vibe on that album. It was five people doing it and we were all working together then. The next album, 'I'd Like to See you Again', was awful. We were all falling out, Simon was leaving, Pete was leaving. The albums reflect how we were feeling really.

Things Change

By the time of the patchy 'I'd Like to See You Again', the band in its original form was falling apart. Tilson had already left, and the rest of the band was splintering. After its release, Terrell left the band, shortly afterwards followed by Topping.

JK : Simon wanted to live in New York. We'd lost that sort of closeness and it reflects in the songs. There are a couple of good songs on there and the playing is a lot better. The musicianship's good, but the feeling's not there. So, that's what I feel about that album. It was a big blow when Simon left, because he was the lyric writer. Then it was pushed onto me, the lyrics and the singing. Previous to that I got to stand off with Donald and play the bass and the drums. I really enjoyed that. That's why my bass playing was good then.

Once I started singing, it had to simplify a lot. I've had to change, and it's taken me about 15 years to work out how to write a lyric. I cringe when I hear the lyrics on the early albums like 'Force', because I didn't really know what I was doing. I was trying, but it was very amateurish and my singing's pretty awful as well. I was trying too hard. On the new album, I think the lyrics are actually pretty good, I've managed to find a way of getting into it.

Now

After a difficult experience with A&M Records, when the band had their shot at the big time and didn't quite make it, its members took a break to pursue different careers and start families. They started touring again as New York bands such as the Rapture and LCD Soundsystem started name-checking them as an influence. As the gigs piled up and the band got back into playing, they started to produce new material. 'Mind Made Up', which was released last year, came soon after.

JK : We're enjoying playing at the moment. We're really happy with the new album, and we've got some good gigs lined up. I think we're worth seeing, if you don't mind watching a bunch of old blokes. We have got back to enjoying it really. We spent a lot of years trying to make it as it were, with A&M and stuff like that, trying to make money and it becoming a living. It just sort of killed it really.

It was very hard work and we did our best, but we didn't quite make enough to give up the day job. so we're all working and we left it for quite a few years. We never said “that's it” and we kept all our gear, but we just all wanted a break. We all got careers. Matt wanted to teach. We had kids and stuff.

Then we started getting the odd gig here and there. We started playing old tunes and thought “Oh, this is pretty good, you know” Before long we'd got an album together. We wouldn't have done it if it wasn't any good really, but it is good. The gigs we've been doing recently are the best gigs we've been doing and some of the old tunes, especially 'Flight', sound better now than they ever did really.

Tunes always sound good when you first write them. The first three months of a tune, when you're playing live, they're great. Then if you carry on playing them and you get too good at it, you sort of lose that magic that you get when you've first written it. I think we're old enough to realise that what it's about is enjoying it and that you can put that tune over in a way that makes it work. It's been working great recently.

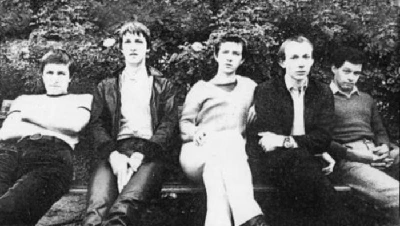

Picture Gallery:-

Visitor Comments:-

|

|

162 Posted By: Mark Kelly, Manchester on 02 Feb 2009 |

So far,it has only been released in France & Germany,are there plans to release it in the UK & where can I get a copy.

|