published: 24 /

5 /

2008

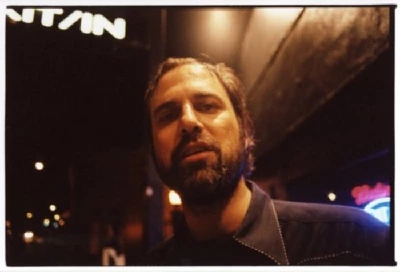

Despite having first formed in 1994, Nashville-based alt.country band the Silver Jews only played their first gig three years ago. Frontman David Berman talks to Mark Rowland about why his group just started touring so recently and their new album, 'Lookout Mountain, Lookout Sea'

Article

London's ULU could be an assembly hall in any school or college in Britain, maybe even the world, if it wasn't for the band playing on its stage and the hundreds of sweaty, excited people standing in front of it. At this moment, this unassuming hall is something else entirely.

The band on stage is the Silver Jews and they've brought with them the dusty romanticism that usually comes with vintage country music. The music the Jews play is country, but not quite; though they have come far from their ramshackle debut, 'Starlite Walker', their music still carries hints of it. Each member of the band is clearly talented and plays their part with gusto, but no one is watching them as much as they are watching their singer.

David Berman, suited and booted, commands the stage and his crowd's attention confidently, exuding a jittery charm that is akin to that of Pulp frontman Jarvis Cocker. The two men even have similar builds. Berman strides and croons across the stage like a club singer made good, complete with 70's style shades. He comes across as a man enjoying himself.

It is hard to believe that Berman only started touring in 2005, eleven years after the release of the Silver Jews first album. That tour came at the end of a long and difficult period for Berman. Deeply depressed, he lived an almost hermetic life for a large portion of his thirties, struggling with substance abuse. 2005's album, 'Tanglewood Numbers', broke that cycle and Berman used touring as a way to get out more. It appears to be working, with the band's new album, 'Lookout Mountain, Lookout Sea', receiving largely positive reviews and moving the band further down the country route. Berman has described it as very different from previous albums and in some ways it clearly is, with a linear change in tone from first track to last. It is perhaps a more hopeful record than its predecessors.

The Silver Jews have always been associated with Pavement, due to the occasional involvement of ex-Pavement members Stephen Malkmus, Bob Nastanovich and Steve West throughout the Jews career. As Pavement's success overshadowed that of the Jews, they were often unfairly described as a Pavement side-project. The band have always been Berman's project, however - the line-up has changed for almost every album - just one of many tricks that Berman used to avoid doing the same as other bands. Now undertaking his second tour, it seems as if Berman is ready to embrace regularity for his band of 19 years.

Speaking on the phone from his home in Nashville, Tennesee, Berman sounds more nervous than his stage presence suggests, but is still very open and at ease with scrutinising himself as an artist, both as a songwriter and a poet.

PB : You've described your new album as different to your previous records and it certainly seems to have a growing sense of optimism about it. What is different about it?

DB : I think it's primarily the way that it goes on the second side. Because the album goes through darkness at the beginning and then the second side is definitely the sunny side of the street. There's a certain sense that a problem has been set up and there is some sort of resolution. Like a film in a way. On previous albums I would say that psychologically they don't make a lot of movement. I kind of see this album as an answer to the problems posed by the other albums. The album contains an exit to me.

PB : Why do you think you've been able to change in this way?

DB : I feel just some artistic evolution going on I guess. There's a certain amount of retardation in rock music, with bands where you sort of learn to do something and the critics tell you what you do in their reviews, it's sort of a feedback loop or something.

It's very unusual I think for songwriters to have second acts. From a very young age I've always been very wary of the career of the songwriter, because it's so short. Infamously short. So I've always tried to identify where I could the reasons for that and try to avoid those things. For most of my career I suspected touring to be the problem, because that's what songwriters do that other artists don't do, to the degree that we work with art that is mechanical reproduction to begin with, because there are millions of CDs made. To go out and reproduce the songs physically night after night to me is a job for an entertainer really, not an artist. I think in a way I've made peace with being entertaining.

PB : I was going to ask you about that. How did you feel about going on that first tour after so many years avoiding them ?

DB : It was frightening and because I'd committed myself to a year of touring before I played my first show. I didn't really want to allow myself to just dip my foot in the water and test it cautiously because maybe I know myself too well. I commit myself to something that may appear over my head and cause a lot of anxiety but then I get through it. So I signed myself up for it, it was like: I'm not ready to do this thing, but I'm going to sign myself up for it, make myself ready.

I think that I feel comfortable with the age I waited to do that. I think at the age of 39, some of those things I was worried about, like the feedback loop of adulation you get from the fans and how it might steal my power...I'm not afraid of that anymore because I feel like I've developed to a certain degree as an artist and I don't feel threatened by having that taken away from me.

I always have in my mind an opposition that helps me because I find negativity more inspiring. I find negative reviews more inspiring; they're painful, they haunt me, but they're the things that I think make me keep trying. So I find that going on tour is a bit of an echochamber and you're sort of protected from knowing. You don't see the fans that were disappointed by this album and didn't come out.

It's like, how does REM go out and tour these terrible records? They're not confronted with how bad they are because they go to the shows and the most hardcore fans are there and there is enough people in the media to give them enough to go on with the whole 'return to form' routine. I think that's scary because any intelligent person outside of REM can see that there's a major problem and that there has been a major problem for many, many years with that band. But the band itself is protected from that. That used to scare me, it was scary when a band would come out and say "this is our best record since..." I'd know it wasn't, I would know clearly it wasn't. Why didn't they know that ? That's why I think I search for criticism and try to flush it out and address it. It's how I've kept my sight.

PB : How did you feel about touring once you had done it ? Did you enjoy it ?

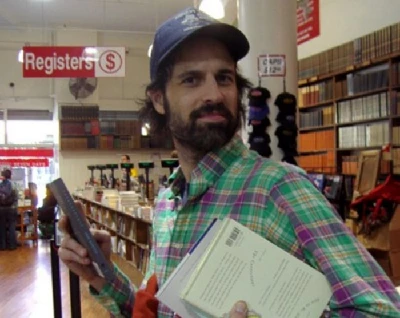

DB : I did. One thing that I enjoyed was the fact that I could do it. I enjoyed that people weren't asking for their money back. It worked. I feel like going on tour is congruent with other life goals I have, as far as being more social and coming out of my thirties, which were fairly hermetic, as opposed to my twenties, which were probably more normal. Touring gives me a tremendous opportunity that most hermits don't get. I could step into the world. I was really surprised when I realised that - hey, I can go on tour. I can do that, I've waited long enough, there'll be interest. Suddenly it seemed very possible to me.

PB : Of course, you write poetry as well as music. How do the two work together?

DB : I think it's taken pressure off both potential careers in that I've been able to steer clear of the English department and the rock club. In that way I've been able to avoid the demands that those two things put upon you. In the rock club it's touring, in poetry it's teaching. Teaching and touring are the two things you can't get out of if you want to be one or the other and I was determined to get out of those things but still practice those arts. I kept one foot in each one, in a way not knowing what to throw my energy behind and it's been interesting.

It's a continuation of other things in my life which is about not being a member of groups. I identified from a very young age that I'm not a follower. I cannot open my mouth at the pep rally at high school and cheer for anything. I didn't understand at that early stage why I didn't want to be involved, but group identities such as being Jewish or being Christian, I didn't really know which one I was. Or being from the North or the South. I didn't take on pre-moulded indentities or roles that society has prepared for you when you are ready to take them on. I was not ready to take on any of these roles. To be a father or an employer, or an employee - I wanted to avoid all those and by saying no to all the things I didn't want to do. I had written myself out of existence almost, at a certain point in my life.

A lot of what I'm doing now is trying to say yes to more things. It's still a challenge. Every time somebody wants me to be on a compilation I have to resist, or people want me to write blurbs for their books and I feel like I have to resist because when I look at an artist I don't want to feel like they're wrapped up in relationships of log-rolling and back slapping good old boys clubs that go on in any society.

PB : Don't poetry anthologies fit in with the expectations of a poet?

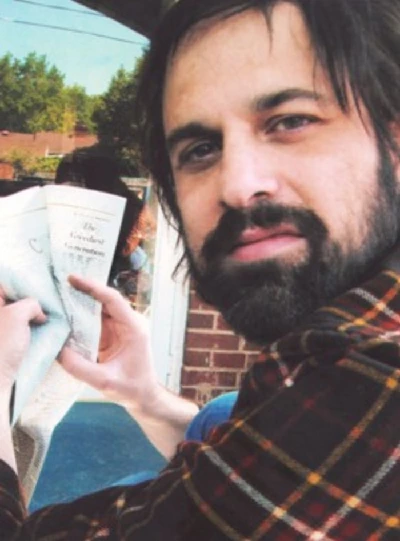

DB : Having poems anthologised doesn't threaten me in the same way as having music anthologised or put on compilation albums. Primarily because I feel like the poems can exist on their own more than the songs. The songs really exist because of the contingency of the other songs around it and they react with the other songs. The one book of poems I'd written was written over so many years that they were not seen to be a set.

PB : When you sit down to write, how do you know whether what you're writing will be a poem or a song ?

DB : The easiest answer to that is that there is not really a point when I'm purely writing and then sort of hustling some things down a path towards poetry and other things down a the path to songwriting. I'm either writing songs or poems and pulling the writing in, so it's never a problem of deciding what it is. I think it's more likely that I would be writing some poetry and I would write a line that could generate a song on its own, like a title or something. That happens. It's been a while since I've written any poetry, so I don't know.

PB : Why haven't you written any poetry?

DB - I think that there is a real reason. I think it's something that I've been putting off for the last couple of years to get back on my feet and just sort of...This is such a terrible example, but Portishead - this is not a band that I really think anything about, but I've really been interested in the fact that they haven't released an album in 13 years. I read reviews of it and people said that it was totally different.

I think that there's some of that effect that I'd like to have with a poetry book, where I want it to have a completely different voice. I'm not interested in doing that album every two years. People let their bands become institutions really, like Pearl Jam. That band's going to keep putting out records, they have no choice in the matter, really. With poetry I don't want it to be treated that way. I haven't taken the time to follow up on it and I guess that's one of the options I have after this tour. Put the guitar down for a while.

PB : Perhaps if you'd got a few bad reviews for your poetry you'd have written more of it.

DB : (Laughs) Yes exactly, I think there's probably some truth to that. I really don't get challenged too much about the poetry - if people like it, they like it if they know about it. With the music I always find there to be some challenge or opposition, so I'm sure that has something to do with it.

PB : Back to the album - it has an even stronger country influence than previous records and less of an indie rock vibe. Have you moved away from indie rock for good now ?

DB : I think it's the nature of indie rock to not write coherent songs with fully realised characters and narratives. It's more of a slap-dash, pastiche type style. I live in Nashville and probably half of the music I listen to is classic country music, so my aspirations when I hear certain great country songs my desire is to write something like that. It's a feeling that I get. I know when I listen to Led Zeppelin that I can't achieve that. My friend Stephen Malkmus will listen to Led Zeppelin and think about how he can get a piece of that, how he can express that kind of power. I know I'm not qualified for that.

Everyone goes for what they're qualified for because they want to be good at what they do. I know I can write these kind of songs and folk songs have always been around. They've always been a very word-based art form. A lot of music now is background music. I had one woman tell me once "there's one thing about your album. I can't do other things and listen to it at the same time." I think there is a lot of instrumental and incidental types of music.

There's not a lot of stories or messages being transferred. I think the iconic band of this era is someone like Radiohead. They're sort of giving you a feeling, of despair or hopelessness, or whatever it is that they give, but there's nothing to take with you after the song is over. I always want there to be something, some sort of folk wisdom, something to put in your pocket when the song's finished. That might be just a desire to be influential. When you're making art you're saying this is worth listening to. More than that I'm saying this is better for you to listen to. It's a response to a lack that I see in music too as well as a response to opposition. There is also, there seems to me, a dearth of good language, certainly compared to the 60's where the songs had to be about something and that doesn't seem to be the case.

PB : It does seem to be an album that is easy to get lost in.

DB : I think that even though I use a verse/chorus/verse type writing structure. There aren't too many repeated choruses. I don't want to let the listener go too much on auto pilot. If they're not listening to me then I think in a way the music fails. It goes under people's standards. If it's just in the background, you notice what's not right about it. It doesn't allow itself to smoothly fit in. For me to succeed I have to get someone to listen to me. If they just sort of hear me, it's not something they're going to put on again.

PB : It also seems to suit this time of year.

DB : All of our records have come out in October. This is the first to come out this time of year, so maybe this is a Summer record.

PB : Why did they all come out in October ?

DB : It's kind of something strange, the band itself has always been sort of variations on a solid theme. I think that despite myself I'm attracted to the franchise or brand style of making things. I always thought that the Silver Jews logo had to be in the upper left hand corner. I'm much more comfortable not proclaiming "hey this is a whole new thing. This is revolutionary." I've always felt that I was trying to do the same thing but better. There are certain songs that have their cousins on the other albums. When you're trying to get a live set together you become really aware that that song sounds like another one from years ago, so you can't play them next to each other.

PB : Doesn't that conflict with your desire to do something new?

DB : As long as what I've done hasn't been corrupted, really been brought into the culture, which I don't think it has, then it's always new to me.

PB : What is it about the brand idea that you like?

DB - I think that I got the feeling from Black Flag albums. They always had the same logo. There's so much music out there, why not make it simpler to lead people back to what you're doing. When I was a kid I had these books in a series, like the Hardy Boys. Part of the thrill for me was to see the different covers when they came out. The basic elements would be the same - the title, the back, the spine, but the front would be different. That was exciting to me.

PB : You can lay them out nicely on your shelf that way.

DB : It seems to me a larger project.

PB : You have a Maher Halal Hash Baz cover on you new album. What attracted you to that song ?

DB : I don't know. It was strange because I always liked that song 'Open Field' and I didn't know what to make of it. It was like a minimalist mystery - where was the child gone? When it came time to record it was the only cover I had in mind to record.

I've been really interested in why I chose it since then, because so many coincidences have occurred around it. I wrote Tori Kudo, the guy who does Maher Shalal Hash Baz and I asked him about the song. He told me it is a reference to Isaiah 65, which I guess is a very important section of the bible for Jehovah's Witnesses - he's a Jehovah's Witness himself. On 'Candy Jail' I quote from Isaiah and I'd never quoted from the bible ever in my life, so I find it kind of hilarious that there are two quotes from Isaiah on side two of the new record.

It was a perfect thing for me to have, I often put an instrumental or an intermission on a record as a way to make space, a way to kind of disappear for a little bit. I think that's the function it serves. It breaks the darkness of side one and it brings some sunshine in. I like it being just after 'Strange Victory, Strange Defeat,' as if the squirrels have escaped out of their bondage and out into the open field in the next song. Are you aware of them?

PB : Yes, I own one of their albums, but I didn't know much about them. I didn't realise they were Jehovah's witnesses.

DB : I always thought it was so weird that I didn't even think about it until after we recorded the song, but their name is Hebrew. They're Japanese, but it's obviously not a Japanese name, I never thought about it. It looked vaguely semitic or Arabic, but I think it's a quote from Genesis. It's a reference to Jacob.

PB : What does the song 'Open Field' mean in relation to Jehovah's Witnesses? This puts their songs in a completely new light.

DB :I actually need to go back to it with the knowledge that he's a Jehovah's Witness. Their version of the afterlife is that they're the only ones left on earth and there are no old people and no children because everybody is eternally going to be 25. That's what he really means when he's saying "no child." I'm glad I didn't know that before. I'd have probably been too creeped out to use it if I'd known that.

PB : Thank you.

Band Links:-

https://www.facebook.com/Silver-Jews-3

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Silver_J

https://twitter.com/silverjews

http://www.last.fm/music/Silver+Jews

Picture Gallery:-