published: 19 /

9 /

2005

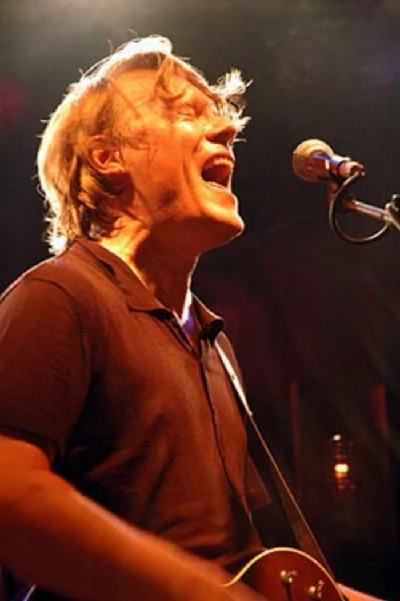

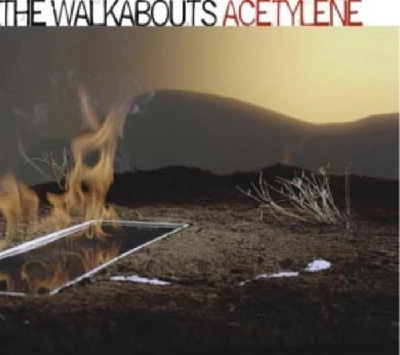

The Walkabouts have just released 'Acetylene', their first album of original material in four years,and their loudest and angriest album to date. John Clarkson talks to frontman Chris Eckman about why after a decade they have gone back to their rock roots

Article

“This don’t seem like the end/It seems more like a bad beginning”-‘Fuck Your Fear’ (‘Acetylene’, The Walkabouts, 2005)

It has been four years since the Walkabouts released ‘Ended Up A Stranger’, their last album of original studio material. While they have collaborated together since then on ‘Slow Days With Nina’, an exquisite five song collection of Nina Simone covers, and also toured Europe in 2003, the Seattle-born group’s members have spent most of their time since then apart concentrating on their own projects. Drummer Terri Moeller has recorded three albums with the Transmissionary Six, the band she fronts with her husband, ex-Willard Grant Conspiracy guitarist Paul Austin. Keyboardist and organist Glenn Slater has worked as a much in- demand session musician, while singer and guitarist Carla Torgerson has opened her own studio and also recorded a solo album, ‘Saint Stranger.’ Chris Eckman, the group’s other vocalist and guitarist and its songwriter, has spent the last few years, since getting married to a Slovenian woman, living in Slovenia’s capital city Llubljana. He too has recorded a solo album ‘The Black Field’, and has also worked as a producer with a rich variety of acts including lush Norwegian torch song balladeers Midnight Choir ; singer-songwriter Terry Lee Hale and Croatian punks the Bambi Molesters.

The Walkabouts, the veterans of fourteen previous albums, have since first forming in 1983 always been diverse, and awkward to pinpoint and to categorise. Signed to the legendary Sub Pop label at the time it had acts such as Mudhoney, Soundgarden and the young Nirvana on its roster, and the grunge movement in Seattle was at its height, the Walkabouts started out as principally as a folk act. The early and mid 90’s found them experimenting with the rock format on albums such as ‘Rag and Bone’ (1990), ‘Scavenger’ (1991) ‘New West Motel’ (1993) and ‘Setting the Woods on Fire’ (1995) . Ever restless, Eckman, however, announced that he was abandoning rock in 1995, shortly before they signed to Virgin with whom they recorded two albums, ‘Devil’s Road’ (1996), upon which they worked with the Warsaw Philharmonic Orchestra, and ‘Nighttown’ (1997) for which they created their own Nighttown Orchestra Always more popular in Europe than in America, they have since 1998 been signed to the German label Glitterhouse, the former European outlet for Sub Pop, with whom they have released three other albums, the elegiac and pastoral ‘Trail of Stars’ (1999), ‘Train Leaves at Eight’ (2000) and ‘Ended Up a Stranger’ (2001).

‘Acetylene’, the Walkabouts new album, despite their own versatile backdrop, is a departure for the group and has surprised fans and critics alike. Caustic and urgent in sound and tone, and recorded in the run-up to the American presidential election in September of last year, but not, however, released until August, it pours withering scorn on the Bush administration and its foreign policy. Eckman in his neo-futuristic lyrics conjures up a nightmare apocalyptic vision of a world in flames. Dead folk singers lie in state, their messages falling onto dead ears. Badly maintained mines stench with poisonous gases. The environment is corroded, and elephants and other animals are slaughtered, all in the name of big business and greed. Supermarkets are meanwhile patrolled by armed guards, while refugees are pushed haphazardly from one transit camp to the next. The first album to feature returning bassist Michael Wells who rejoined the group in 2003 after originally joining the group in 1984 and then leaving in 1996, the music on ‘Acetylene’ finds the Walkabouts returning to their rock roots and, while never without melody, is grinding, guttural and harsh. Detuned, distorted guitars are slammed up against Moeller’s hard-edged drum work and Slater’s jabbering keyboards. Eckman and Torgerson’s vocals are meanwhile breathless and frantic. It is the loudest and the angriest record of the Walkabouts’ career.

Pennyblackmusic spoke to Chris Eckman, who had returned to Seattle for rehearsals and who was back for a second interview with us, about ‘Acetylene’ a few days before the Walkabouts embarked on a European tour.

PB : 'Acetylene' is a very angry album, much more so than any other album you have recorded in the last 20 years. It is a complete contrast to your last few records, both in your solo career and also with the Walkabouts. Did you set out with the deliberate intention of recording something completely different than before or was that something simply that emerged ?

CE : It was a little bit of both. We did a short tour in 2003 and had back with us Michael Wells, who had last played with us in 1996. It is a relative thing when you talk about the Walkabouts and rock music, but he was with us during-shall we say ?- our more rock years and back when we were still with Sub Pop. When he came back, he suggested that we put songs into the set that we hadn’t played in years and so we started doing that and we really enjoyed it.

It could have been a blip or something that just happened momentarily, but then when it came to time to thinking about doing the album I guess that some of that was in the back of my mind. I probably couldn’t have done another quiet album though anyway because what I had on my mind was pretty angry stuff.

I was picking up my electric guitar rather than my acoustic guitar when I was writing songs. It was not so much a question of choice. It was what I actually had to do. It wasn’t even so much about rock music. It was more about dealing with the emotions which it involved and finding the best mechanism for delivering them.

PB : 'Acetylene' is largely an attack on the Bush administration and Bush politics. You’ve lived in Slovenia for a number of years now. It can sometimes be very hard to get angry when you live in the middle of something. You can become numb and desensitized to things. Do you think that the lyrics would have been as angry if you had still been based permanently in America ?

CE : That’s hard to say. You make a good point. When you’re on the outside and looking in you can often see more clearly the way people around you react and how they are affected by things. They haven't had the chance to escape, so maybe you’re correct. When I came back to Seattle to put this record together with the band, I found quite the opposite though. I found the musical community here in Seattle completely politically sensitized and awake and angry, just crazed about the election which was then about to happen. A lot of the emotions you hear on the record are not just to do with the songs. It’s also to do with the five individuals that made it. We were all well honed in about what we were feeling and our pistons were all firing together.

PB : You recorded the album in September of 2004. That was just a couple of months before Bush got back in. Was there a sense of inevitability about this album ? "This guy is going to get back in again. God help us all !"

CE : Yes. We all knew that he was going to get back in again. I don't think that there was any sense that this was a situation in which the events were going to be turned around.

There are some things, however, on 'Acetylene' that go beyond it being an anti-Bush and anti-foreign policy record. I think a lot of it had to do with people’s frustrations about inevitability and just finding yourself in a situation which you violently disagree with on a moral, emotional and whatever other level you hack it, and just not knowing what the hell to do about it other than to maybe grab your guitars and to make some noise if only for yourself. 'Acetylene' is also an escape valve, maybe just for our own emotions.

PB : Did you want to shock people with 'Acelytene'? It starts with a track called ‘Fuck Your Fear’, which is a pretty confrontational way of starting any album (Laughs). You’ve developed a reputation in recent years and actoss your last few albums for being fairly quiet sounding. Did you want to destroy any previous conceptions that people might have had of the Walkabouts ?

CE : To be quite honest I never thought about it. The yardstick we used was how real it felt. If that meant having a track called ‘Fuck Your Fear’ on it at the start then that was what it was.

I didn’t think about the audience at all when we were making it. We were actually quite surprised. We played two shows here in Seattle on the two days before we began recording the record. We played on the Thursday and the Friday night, and then on the Saturday we walked into the studio and started to make the album. At those two shows we played these songs, strictly in the way that you hear them on the album.

The audience was shocked, but what was interesting about it was they got it immediately. That was the other side of it. As much as we saw jaws dropping for the first minute and a half of 'Fuck Your Fear', nobody was confused at all beyond that. They were just like “Wow ! This makes perfect sense.” They got it immediately, so that gave us a lot of confidence to think even less about how people would react to it and to just use our own measurement for it.

PB : You put the album together very quickly. You rehearsed it in three weeks and then recorded it in another three weeks. It’s a very urgent record. The Walkabouts have often in the past spent up to a year working on the arrangements of an album. Did you record it quickly because you wanted to build on that sense or urgency, or was it because the band all has other commitments now and time was limited ?

CE : It was a bit of both, but it was more down to the first. Commitments can always be worked around. We’ve always arranged things that way even during the last six years that I have lived abroad.

When there is a will, there is always a way to find how to make a record longer. I’ve got my own studio in Slovenia. Carla's got her own studio now in Seattle. We could have overdubbed for years on this record if that had been the choice. Once we had got the basic tracks down we could have gone on recording indefinitely for no cost at all.

It wasn’t so much that. There was a real strategy to making the record. It needed to be done quickly. It needed to have this attitude that we were playing for keeps. I don't want it to seem like I am boasting. It's not really a question of arrogance, but we didn’t replace any guitars on this record. There is not a single place that the guitar that you hear that is not the guitar you hear with bass and drums. That was something which we all felt we had to have. If there are a few mistakes, you just leave them. You’re just going for those moments. You just see what happens. That doesn't mean that we got everything at first takes. Some of these songs we were 20 takes into the process before we got the right one.

PB : You recorded 'The Black Field' in a very raw fashion as well. You can hear the door of the hairdresser’s upstairs from your studio in Slovenia slamming shut, and the noise of your guitar brushing against your jeans. Do you feel that you might be going in that sort of direction anyway ?

CE : The idea of doing things very quickly is an aesthetic that I really valued when I was much younger and which I still do. The best and the most real takes tend to be the one when you just sit there with everybody and turn on the tape and see what you can get. I still believe that there are other kinds of records to make, but I do a lot of producing, and especially when I work with bands I feel that you have got to go in and capture a moment. Then you can take a step from that point into something more abstract and more detailed. I think that it is really beautiful if you have that initial sense of everybody playing together. You’re not after perfection, but some kind of feeling.

PB : The album has been described in your press sheet as “nearly a punk album.” Do you see it that way ?

CE : Well, I think all our albums are punk records (Laughs). For me punk rock was never a sound. It was an attitude. It was about doing exactly what you wanted to do and not listening to anybody else or taking bullshit from anybody. If you used a symphony orchestra to accomplish it then that wasn't a problem really. The Clash were wonderful for that. They took that punk aesthetic and said “It’s not really about three chords and punching your first in the air. It’s just about experimenting and going for it.” 70's punk was the most important musical moment of my life. I have always thought about the Walkabouts as being a punk rock band. I always had this fundamental idea that you don’t follow trends. You don’t listen to people. You do whatever you need to do.

PB : The penultimate track on 'Acetylene', ‘Before the City’, finds its narrator wandering around a city which seems to be on the verge of collapse and which has gone to absolute moral hell. Were you thinking particularly about Seattle when you were writing the lyrics for that song ?

CE : I did actually polish those lyrics off when I was in Seattle, but it could be a lot of places. It could be Seattle. It could be in London. It could be a lot of places 20 years in the future from now. That was the idea behind that, a future which looks a lot like things do now, but which is a little more crazy, and which finds us even more in the moral wilderness.

PB : On 'Fuck Your Fear' you sing “This don’t seem like the end/It seems more like a bad beginning.” Is ‘Before This City Wakes’ then the “bad end” ?

CE : Yeah ! And 'The Last Ones', which then follows on from that is about the last survivors of humankind. On that they are standing looking at what is left and what is not left.

What was a technical point, but is rather strange was that we actually recorded 'Acetylene' in the sequence that you hear it. We actually said “Here’s the first song” with 'Fuck Your Fear' and began by recording that. Then in the last day in the studio we recorded ‘The Last Ones.’

In the rehearsals it started to take form. It became really like a piece. There was a certain dramatic art to it. The songs needed to be exactly where you hear them. They wouldn’t have worked anywhere else. The record functions from this song to that song, so there was a purposeful, thematic grouping to the tracks.

PB : ‘The Last Ones’ couldn't really be described as gentle, but it gentler than the other nine tracks of the album , which are a complete assault on the senses. Did you want to put that one on the end simply because it is softer ?

CE| : It would have been hard to put it anywhere else . There is a philosophical vent to the lyrics about taking stock of where you have been, who you are and where you are going, and is there a place to go ? There is a refrain on it about heading for home, but there is no place to go. You’re left in this ambiguous world of like where is home now, and where can you possibly go ?

I guess that in some ways as bleak as that might all sound it is also meant to be in other ways loudly optimistic, as the people who are the narrators-both Carla and I sing it together-are still looking for something. They have not just resigned themselves to everything which you have just heard.

PB : The album was produced by Tucker Martine, who is something of a name producer at the moment. How did you become involved with him ?

CE : Tucker is a friend of mine. I have known him for a long time. He lives in Seattle. He’s got a studio there. I did a mail order only solo record for Glitterhouse called ‘A Janela’ when I lived in Portugal and he polished it off for me. That was really the first time I worked with him. I also produced an album for a singer-songwriter called Terry Lee Hale. Tucker and I did that together with him, and of course I know his work with the Transmissionary Six, Jesse Sykes and Laura Veirs. He did the last Laura Veirs record 'Year of Meteors.' In fact he has done all of the Laura Veirs records.

'Acetylene' was a funny record to pick Tucker for, because he is known, as you described the Walkabouts, for also making softer and more detailed kind of music.

The reason why I wanted him to do 'Acetelyne' was because first of all I like him very much, but also because he is a guy that listens to a vast amount of music and I knew that there was nothing that you could throw at him that would in any sense throw his game. He was quite excited about doing this record because for him it was such a different kind of thing and he could exercise different muscles than he usually gets asked to do.

PB : What do you he think he brought to the recording ?

CE : I think that he had a very clear idea of how the record should sound even before we started recording it. It’s a very dry sounding record. It’s very upfront and he felt that had to be a really important element, that we needed to make it completely transparent, and not shadowy, not gauzy and not opaque. It needed to be upfront and right there. "Here it is ! Accept it or not !" He really made sure that it was like that all the way through. Whenever it looked like we might get away from that, he steered it back into place and to where it should go.

PB : Is it true that you all recorded the album facing each other in a half circle ?

CE : We did. Yes, with everybody looking at each other. I saw some pictures years ago now of Neil Young recording in his ranch with Crazy Horse and that was how they were set up. He was looking straight at the drummer, not turned away from him, looking right at him, and everybody else was in a half circle.

I thought that was a great way to record with everybody able to see each other’s hands and so we decided to try that on this record. Synchronized things happened on this record that were easy to do because we could see each other, where the person next to you's hands were going, when the snare drum was going to be hit and things like that. There were all these visual lengths that were just wonderful and which made the album tight in a cool way.

PB : It was recorded on analog tape. In the footnotes on the sleeve it says that it was recorded it on analog tape and then there is an R.I.P. beside it. Why did you put that on it?

CE : Shortly after we recorded 'Acelytene' analog stopped being produced. You can’t buy it now. There is a manufacturer who started up this summer who is picking up the slack, but it’s pretty much being phased out. It’s getting harder and harder to find it. It is becoming more and more difficult.

I think it is a great loss. It is a wonderful medium. On the records that I have produced for other people I have tried to insist that we use it, but it is getting more and more difficult not only to get it, but also to justify the expense because it is also very expensive.

PB : You have said in your press release that you had a lot of fun recording this album. Why was it fun ? Was it just because it has been a long time since the last Walkabouts album and it was great to get together again and also to find yourself doing something completely different ?

CE : It was because of the camaraderie aspect. When you make a record like this everybody has to help each other to rise to where you need to go. When you have a really technical recording with each person recording separately things can become quite isolated. You quickly evaporate any kind of band feeling. We never lost that band feeling with this record. We did it fast and we did it in such a way that the way you hear it is basically the way that we played it. There was a lot of humour in it as well. A lot of the emotions on the record were pretty heavy. When you have a bunch of people in the room sharing that you can also find the humour, the absurdity of it and that can also make it fun.

PB : The album was recorded a year now. Why has it taken so long to come out ?

CE : Glitterhouse already had a 16 Horsepower record expected in the spring, so that was one reason for the delay, but then 16 Horsepower split up (Laughs) and we were left hanging and thinking “What we should do ? Should we rush it out now ?” But we decided “No, there is a schedule that we are on. If we start to rush, things will start to suffer", so we decided to to stick to the original course. I think it has worked out fine.

PB : Perhaps the record is even more timely now that Bush has got back in. Would you agree ?

CE : Yeah, definitely. When you make a record like 'Acetylene' there is always that possibility that maybe tomorrow you’re going to wake up and all the birds are going to be chirping, and the world’s going to be beautiful and everything’s going to be wonderful. I would trade that for the currency of the record absolutely, but sadly in this case the very depressing conclusion is that things are even more the way that we hear them on this record.

PB : You’re about to tour Europe. What are you going to be playing on this tour ? Are you going out to play the album as you did in Seattle or are you going to be doing a mixture of old and new material ?

CE : It is going to be a mix of old and new, but it falls pretty much on the more aggressive side of things. We really did a lot of soul-searching, like “What do we do ? Should we play a lot of the pastoral stuff, and to try to mix it with this album ?” The conclusion of that was that really in a lot of ways would dull a lot of what we’re trying to do with this, so we selected a collection of songs that in many ways reinforced a lot of what was on this record. It is very much a rock show. It’s hard to believe. I vowed in 1995 that I was not going to play rock music ever again, but here we are doing it again (Laughs).

PB : Carla has said that she feels that the Walkabouts had lasted because they have never achieved that sort of massive destructive success which happens to so many bands that do become very successful, but that you have always achieved enough success to continue to make it interesting. Would you agree with that ?

CE : I think that is pretty much dead on. I think that is a pretty good analogy. As we never achieved that kind of success the goals we have are still basically musically-orientated and are dictated by the music. We’re all still trying to eke our livings out in whichever ways we can. The Walkabouts are just a part of what I do professionally, but in a good way that takes a lot of the pressure off. We’re pretty free as a result to do what we want to do.

We have got egos too and we want to sell records. The advance sales on 'Acetylene' are really good, and that makes me feel great (Laughs), but I don’t have to sit around as a result and to calculate exactly how many copies we have to sell. I knew that when we did ‘The Black Field’ that very few people would buy that record. I was correct (Laughs), but that didn’t stop me from doing it. I knew that even before I recorded the first note on it. It is just about doing what you need to do at the time. It is about freedom.

PB : And that leads me on to my last question. You have recorded this album which is different in from your last few records and in many ways from any record you have done before/ Where did you go from here ? What are your plans for the future once the tour is over ?

CE : It is always hard to see. We have all got a lot of enthusiasm about the Walkabouts now. I can see us jumping into another record, but I think we will know more at the end of this tour. I don’t really try to make plans though. As I said to you, I announced to the entire band in '95 that I didn’t want to make rock music anymore, and now here we are and I have moved the whole thing head round again(Laughs).

As I get older, I just try to let the things that I want to say happen. The sound you use has to reinforce that. Sometimes that can be very quiet acoustic music, and sometimes it can be really loud. It just depends on the songs and where they are gravitating.

You don't always know how things are going to be when you start out. When you sit down to write you’re not always sure what is going to come out, so I try to keep it as loose as it can be. Once you commit to a project a lot of that looseness disappears. You have to get in and to find a way to complete it. Up until that point I try to keep it as loose and as undefined as I can.

PB : Thank you for your time.

CE : Thank you too.

Picture Gallery:-