published: 17 /

10 /

2004

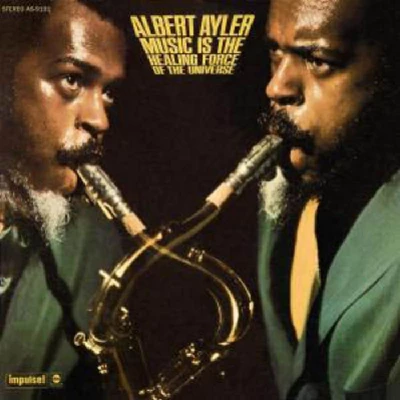

One of the pioneers of the free jazz movement, saxophonist Albert Ayler died mysteriously at the age of 34 in 1970. With 'Holy Ghost' j, new box set of his work, just out, Jon Rogers looks back over his short life

Article

Free jazz snubbed its nose at the established order, and in an era where the "establishment" was increasingly under assault, it became a rallying point. A musical signpost that directed the listener to flow against the tide. The free jazz style had the same socio-political and cultural parentage as acid rock, campus demonstrations and the whole 60's counterculture movement. It was the age of cold war paranoia, civil rights demonstrations and protests against the Vietnam War. Jazz needed to reflect the times and this couldn't be done, according to acclaimed tenor saxophonist Albert Ayler, using the more conventional methods of cool or bop jazz. "For me, [bop] was like humming along with Mitch Miller. It was too simple. I've lived more than I can express in bop terms. It's a new truth now. And there have to be new ways of expressing that truth."

Ayler though didn't totally dismiss the bebop style of Charlie "Bird" Parker and whilst he was attending his local college in Cleveland in 1954 he was still trying to master the bebop style, earning his then nickname "Little Bird" and trying to master the alto sax. "I was impressed by the way he [Parker] - and later Trane [John Coltrane] - played the changes" remembered Ayler.

When he was growing up in Cleveland, having been born in 1936 into an upper middle class family, he would play in church with his father, whom had introduced the young Ayler to swing and bebop. Whilst a teenager he would supplement his formal saxophone studies with playing in rhythm and blues bands as well as summer stints with bluesman Little Walter. When he was 22 he served three years in the US army, playing in army bands, occasionally performing on European bandstands while stationed overseas, mainly in France, and managing to take in some of the free jazz sounds that were filtering through. It was during this time in the army that he switched to the tenor sax: "It seemed to me that on the tenor you could get out all the feelings of the ghetto. On that horn you can shout and tell the truth."

The free jazz style strongly resisted wider acceptance from the public. After all, it's never going to be played as soothing background music in some over-priced coffee shop whilst its clientele gently sip a latte. The harsh, disruptive, abrasive style polarised critics and audiences comprehensively. People were firmly in the for or against camps with no undecideds. Those in favour lavished praise while the critics simply thought the genre simply adhered to William Shakespeare's description: "sound and fury signifying nothing".

Over the years Ayler's work, along with others such as Pharoah Sanders and Cecil Taylor, would increasingly gravitate toward longer, uninhibited, loosely structured explosions of sound, initially coming from the wholly atonal New York avant-garde free jazz. In interviews Ayler would explain that the goal was to escape simply playing notes and to enter a new aesthetic vision where the tenor saxophone created sound. The traditional scales of Western music were incapable of encompassing Ayler's bellowing and moaning spasms. He was a virtuoso of the coarse and anomalous with a range that went from out of tune waverings to barks and high-pitched squeals. According to jazz critic Richard Williams, Ayler "brought back to jazz the wild, primitive feeling which deserted it in the late thirties... His techniques knew no boundaries, his range from the lowest honks to the most shrill high harmonies." He effectively pushed the vocabulary of the saxophone to its limits.

There was also a conventional and traditional aspect to Ayler's playing. Along with his free form expressions and African American influences, compositions also drew on ballads, marches, polkas and folk songs, often of a quasi-European nature for his free, atonal, usually ecstatic improvisations. Despite his interest in the avant-garde he constantly referred back to more traditional music forms, even getting inspiration from the musical dirges played at old New Orleans funeral processions.

Despite his apparently violent, chaotic music, Ayler himself was by all accounts a gentle and modest soul, drawing deeply on his religious beliefs and ideas of peace and spirituality. "I'm getting my lessons from God," claimed Ayler. "I've been through all the other things and so I'm trying to find more and more peace all the time." His religious conviction as well as wider spirituality is clearly evident. Even a superficial scan over the songs reveals titles such as 'Spirits', 'Saints', 'Our Prayer' and 'Spirits Rejoice'. The new, deluxe box set of nine CDs has the title 'Holy Ghost'. "We play peace" was effectively Ayler's motto. The theme of religious love is constant and is also present in other contemporary jazz recordings such as Don Cherry's 'Complete Communion', Ornette Coleman's 'Peace' as well as Coltrane's 'A Love Supreme' and 'Ascension'.

Ayler along with Coleman, Coltrane and Taylor were the main cornerstones of free jazz, often playing with one another at various different times and invariably influencing each others' style although Ayler is perhaps the least celebrated but arguably the most radical.

After his army career he decided that he was more suited to the European aesthetic and so relocated to Scandinavia rather than return home to his native America. To earn a living though he effectively had to play the standard jazz canon rather than the more experimental pieces that he preferred. Often though he would use those standard and familiar tunes as a launch pad for the occasional wander into more challenging areas.

Ayler's first Scandinavian recordings made in the early 1960's see him struggling against the prevailing jazz tradition but it is in 1964 when he really develops his own, mature style, helped to a great extent by sympathetic musicians such as drummer Sunny Murray, bassist Gary Peacock and Don Cherry, who frequently sat in with Ayler and eventually joined the band. The quartet recorded the staggering 'Witches and Devils' in February 1964 which saw Ayler make a decisive break from the conventions of bebop, drawing on the likes of Coleman and Coltrane for inspiration.

The trio of Murray, Peacock and Ayler then went on to record 'Spiritual Unity' which became Ayler's defining statement and secured his reputation. Jazz critic Richard Williams called it "a kind of extemporised chamber music of astounding subtlety." 'Spiritual Unity' ranks alongside Ornette Coleman's 'Free Jazz' and John Coltrane's 'Ascension' as a defining recording of the free jazz movement of the early 1960's. It launched a blistering attack, encompassing frantic explorations of harmonics, strings and general unpredictable eruptions of molten musical lava that gushed forth.

Later, Ayler's brother Donald would join the band on trumpet with his collage style largely complementing his sibling's frenetic work and saw his style expanded to incorporate elements of rock, R&B, blues, gospel and even bagpipes. This broader style wasn't so warmly welcomed by fans of his earlier style and was rejected by the dominant rock audience of the day. The squealing, battering noise though continued but was toned down.

In November 1970 Ayler simply disappeared with his body turning up three weeks later in New York's East River. He was only 34 years-old. The medical examiner's office recorded that death had been caused by drowning but his death has been surrounded in mystery ever since. Some commentators saw foul play with rumours circulating of Ayler's corpse having a bullet wound in the back of his neck while others concluded it was suicide with Ayler suffering from depression brought on by the breakdown suffered by his brother and mental instability.

In his short life though Ayler managed to leave behind an astonishing body of work that has had a far-reaching influence on music, and not just in the jazz world. Along with Ayler's obvious influence on John Zorn and people like Lester Bowie and David Moss he has also affected the works of Bill Frisell, Sonic Youth, Peter and Caspar Brotzmann and Vernon Reid. Even Bruce Springsteen's 'Folk Song No 1' is an unabashed tribute to Ayler, while hardcore singer Henry Rollins, who did a guest appearance as a DJ on an LA college radio station in 1990, played over 30-minutes of Ayler's music as part of his set.

Picture Gallery:-