published: 22 /

11 /

2002

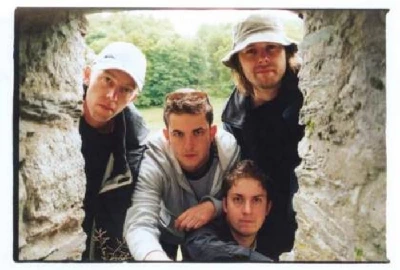

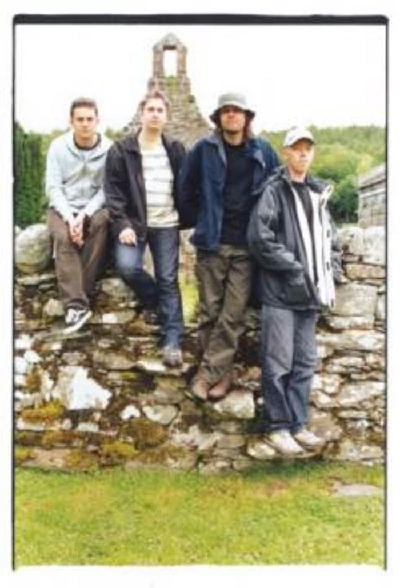

London band Candidate's new album, 'Nuada', is a homage to the film 'The Wicker Man'. Written and recorded at the film's original locations, Joel and Alex Morris from the group talk about their extraordinary pilgrimage to make it

Article

Candidate’s 'Nuada' is an album based on 'The Wicker Man', the 1972 Edward Woodward Brit-horror film featuring dodgy pagan practices, a burning effigy and Paul Giovanni’s excellent folk soundtrack. Woodward's co-star Christopher Lee called the soundtrack “probably the best music I have ever heard in a film.”

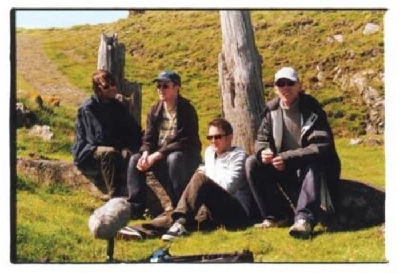

The band set out to recapture the spirit of the soundtrack while not going down the “tribute album” route. They spent time on Summer Isle, where the film was shot and set, soaking in the atmosphere and making music.

The band are signed to Snowstorm, home of the eccentric indie wit Chris T-T and erstwhile purveyor of fine quality Christmas records, including Candidate’s own (non-ironic and oddly beautiful) cover of East 17’s 'Stay Another Day'. They have released on Snowstorm various singles and EPs, and two previous albums, 'Taking on the Enemy's Sound', which was released in 2000, and 'Tiger Flies'which came out in 2002

'Nuada' is a very beautiful work, evoking the hazy sunshine of the time and place it was recorded, while having a 'Forever Changes'-like darkness lurking underneath. Like the Love album, it is tinged with sadness and a hint of menace, but always as an understated subtlety rather than being overtly ‘dark’. It features Jason Hazeley of indie duo Ben and Jason and some distinctive guitar magic from British folk legend Bert Jansch.

Early copies of the CD include a video of the documentary short, 'Singing and Dancing' on a Sunday, chronicling the band’s time on Summerisle.

I met up with singer Joel Morris and his brother Alex [nominally guitarist but like the others, multi-talented] about as far from Summerisle as you can get, on an inappropriately rainy November day in North London.

PB : How’s the promotion trail going?

JM: It's sold really well; the promotion's going really well. The last album sold well and so this time round everyone's been really much more friendly about it.

PB : Is the album doing well in the shops?

JM: It's such a bad time of year to release an album, because there are so many albums coming out, and if you're on a little tiny label you want to release stuff at the quiet time. But this time we're trying to compete with the big boys at the time they're releasing all their heavy guns. We're up against 'The Best of Elton John'... But it's doing really well, we're getting a really good response, so we feel slightly vindicated for that.

PB : What is Snowstorm like as a label?

JM : Snowstorm started off very much as a homegrown label. It was all done by people remortgaging houses and borrowing money. There's no budget.

AM: Snowstorm is entirely self-funded. If your record pays for itself then you've done well and you can have another one.

JM: Each record pays for the next record to be made. But the great thing about that is there's absolutely no pressure - you can do whatever you want to do. This was originally just a project - an album about 'The Wicker Man'. We worked out, as long as we sold about 1000 copies we'd be alright.

PB : Why did you choose 'The Wicker Man' as the basis for an album?

AM: We're really big fans of the film. We're always very wary of the whole schtick of 'The Wicker Man'. We didn't want the project to come across as something just for us “only if you're into the cult of the film would you understand it”.

When the pitch first came around, we thought: “should we do covers?” We were all aware that if we did that we were going to get labelled as complete... tossers. All we wanted to do was basically translate our enjoyment of the film and love of the soundtrack and try and recreate something along the lines of what they were doing. So for someone who hadn't seen the film, you could take it as a straight album.

JM : We've been into the film for years and years and years. It was one that had such a distinctive soundtrack that we've borrowed from before.

PB : I'd actually listened to the album before seeing the film.

JM : Our album's a lot less scary than the film. It's a much friendlier record. It's confused a few people, because we didn't want it to be a gothic album or a horror album, which might be the obvious thing to do, if you were Marilyn Manson or Iron Maiden.

We wanted to do something that was bucolic and pastoral and friendly and was like the music you'd hear on the island. So we took something out of the film and made it very... us. It comes out as being more of a folk record than a film tribute album.

PB : What were you listening to at the time?

JM : What really interested me was that we made a conscious decision with the last record and with this one to go back to late sixties and early seventies folk. We just didn't feel that anyone was really doing it. We thought it was a really good influence to start plundering, because we really liked it, and we hadn't really heard anyone else trying it, apart from maybe Gorky's, but that folk thing hasn't been plundered.

Every time we meet someone like Bert [Jansch] we go, "well you were doing this 30 or 40 years ago". If we can pick up from that and carry on doing that, it's a lot more interesting than hearing just another band who come out and rip the La's off, or the Stone Roses. It's just a little bit more interesting.

AM : It's quite important that we weren't trying deliberately to reinvent ourselves as a sort of indie-folk band. I think we would have headed that way anyway. With the first album's Americana influences, stuff like Grandaddy, it sounds like that was the forced aspect - we weren't doing it deliberately.

JM : When we went back and listened to the old tapes it was quite interesting, we were going, “why were we resisting the folk influence?” You could hear we were straining to do more acoustic stuff, more three-part harmonies, more finger-picking, and the moment we decided we were actually going to do that the band just relaxed. The sound got better, the songs got better, we went, "ah, so this is what we sound like".

AM : I think you get that with lot of bands: their first few albums they're trying to work out what they sound like. You reach a point where you suddenly go, ah, that's what it sounds like. One of the happiest things is that it's only taken us two albums to work it out, and it's relaxing to have a sound that we're happy with. Lots of people don't like it or don't understand it, but loads of people really do. We can keep doing it and people will keep enjoying it, keep buying it, hopefully.

JM : 'Tiger Flies' is very much a folk record, but there are a lot of other influences going on. It’s like Brian Eno crossed with folk. Basically we used electronica and loops and drones and found noises: a couple of bands have done that recently, like Simian and Fourtet. You've got real strings and you think it doesn't sound right, so you put something fake in there and it'll give it… not an edge, but it'll be fairly arresting.

AM : What I love, one of our favourite tricks is to match these things. When we were doing 'Nuada' we thought “do we get violinists and flute players? No, it's much more fun if we do it the same way as we've always done it.” Use a loop instead of a real flute, and we discovered that instead of doing it as a really fake album we’d take the spirit of the original, and add what we'd normally add: echo and synthesisers. The synth we used most on 'Nuada' is a [Yamaha] DX7 which is like a Miami Vice synth, a really bad 80s synth, and it sounds great against an acoustic guitar and a folk vocal, so why does no-one do that?

JM : No-one in the 80's was doing fingerpicking over synths. Someone said that “Good taste is the enemy of creativity”. We can't take credit for it, there are those trailblazers out there who make you think that these things are possible. Gorky's for me, the Super Furries, anyone weird. Like with Pavement, you can stick the naffest thing possible over the coolest thing possible and it would make it cool.

If you take two different things and lay them together you've got a pretty good chance of doing something no-one's done before. And it might sound bloody awful, but we lucked out. I think the spirit of all our recordings – one of the things I hope you can hear over our recordings - is that we really enjoy what we're doing.

PB : You got to work with Bert Jansch on 'Nuada'. How did that happen ?

JM: Our manager gave him a copy of 'Tiger Flies', and he really liked it. He's incredibly shy - very very clever, but incredibly quiet. He spoke very fondly of it in magazine interviews that he was doing, and we got together from there.

I had never really heard his music. We thought he might be quite antisocial, because a lot of folk's quite boring and mimsy, and every time someone said he was a really good guitarist, I'd ignore them thinking he was just [mimes a Joe Satriani guitar widdle].

When we heard him play, it was like, “No, you've got loads of influence on what we do, I feel like an idiot for not being into you years ago”. I think had we known more of his stuff before we did that session I wouldn't have been able to do the record with him. I was sitting there going, “you're really good”. He was so nice about it, so lovely to find someone that good who afterwards you realise “Right, your influence is gonna be all over this record.”

AM: Also the guy was completely self effacing, very very shy about it for someone with that much ability. When you get someone like that with so much ability, with no need to be, there was an awe there.

Is self doubt important to you as musicians?

AM : I don't think you should apologise for making a record, but on the other hand if you shout about it there are loads of people waiting to knock it down.

JM: One of the most profitable things you can do when you're making a record is engage in asking, every day, is this any fucking good or not? I think that's why some of the worst records ever were made on cocaine. One of our principles is that whenever we record something off our faces, the first thing we do when wake up the next morning is listen to it absolutely stone cold sober and say “is it any fucking good or not?” You have to get a balance between absolute wild abandon when you’re recording and absolute precision when you're arranging the album.

PB : What is it that makes the album different for you?

AM: I think a lot of it was based on the pleasure that fans get from listening to an unreleased track or a live recording by their favourite artist. Something that was done by Nick Drake in his bedroom, while he was drunk or whatever. And you think, that's just him and a guitar, you don't need anything else. There's no-one else there pontificating on whether it needs a synth over the top or whatever - it just sounds great.

The logic was, if we could do a whole album that was done kind of like that, it would give the whole thing a unity which you don't get when you say, right, we're going to need a track that sounds like this or that, whatever's selling at the moment. We realised, if we did them all straight, the tracks wouldn't need anything, and if they did we could go back afterwards and add it.

JM: Because it was going to just be a novelty stopgap it's got that sort of rawness about it. The worst thing for a record is for you to think it's terribly important, because you tend to make all the wrong decisions. During the sixties bands would be producing three albums a year, there was no way that people were going, “this is going to be your ultimate artistic statement”, and they'd just do whatever felt good on that day. And that always sounds better. We work so much better when we're relaxed than we ever did when people were talking about major record deals...

PB : Would you ever move to a major label?

JM : No. We got offered deals before and the people who offered them were... wankers.

AM : You got the feeling that if you got on board this horse it'd be really uncomfortable.

JM : And it was very exciting because it'd allow you to give up your day job and whatever, but at the end of the day what major label artists really want is the kind of creative freedom we've got for free. I'd rather have a little less money, or no money as we're currently making, but have records out there that aren't a complete embarrassment, that are actually something we've done.

You're releasing records with your name and your face on them and you're not happy with them. If our record is shit, it's our fault, it's our problem, we don't have to worry about the record company.

PB : Do you make a living from the band?

AM : Not at all – I've got to back to work in a second...

And he’s not lying. A few minutes later, having waited for the floods to falter, talking about the impossibility of being both creatively independent and rich as a musician, their anti-purist love of pop, rock, soul and all points north, Joel and Alex have to take their leave.

Picture Gallery:-