published: 25 /

10 /

2023

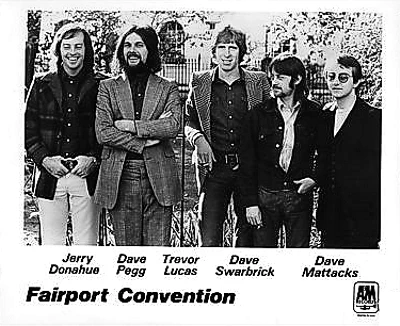

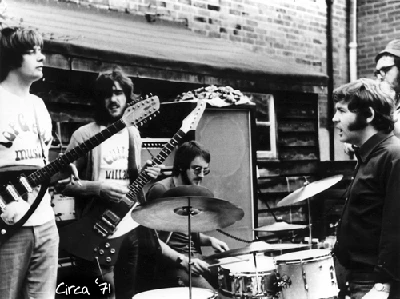

Legendary drummer and percussionist Dave Mattacks talks to Adam Coxon about his on-off career with Fairport Convention, working with The Albion Band and session work with Paul McCartney and Richard Thompson.

Article

Legendary drummer and percussionist Dave Mattacks is a longstanding member of one of the most iconic groups of all time and a highly in demand session musician. Joining Fairport Convention in 1969, Dave played on a clutch of the group’s classic albums. He left to join the Albion Band in 1972 but his close association to Fairport continued throughout the years and Dave is currently touring with them in 2023. Amongst his many recordings as a session musician since the 1970s, he has worked with Richard Thompson, Paul McCartney, and George Harrison.

PB: When did your last tour with Fairport? I know that you did a show for Peggy's 75th, was it, last November?

DM: The last time I toured with Fairport would have been the back end of the 90s. I did the one off for Dave Pegg’s 75th, which was a lot of fun. And I've been doing, apart from the two years off for Covid, a guest spot at the Cropredy Festival. But the last time I actually did a tour with Fairport was the back end of the 90s, the last one just before I left.

PB: What do you think it is about Fairport that's always kept you coming back? I know that you left in 1972 to join the Albion Band but it seems that you've always been associated with Fairport throughout your career, even if it’s been playing on a John Martyn record or playing with Richard Thompson on his albums. What is it that brings you back to Fairport all the time?

DM: Well, I suppose it's somewhat of a cliché, but it's people. I mean, we grew up together. I don't think about it like a lot of my peers in similar positions. I don't think about it a lot, but when it does cross my mind, I realize that I've known Simon (Nichol) and (Dave) Peggy for a long time! I joined in 69. Peggy joined, six or nine months later? I mean, that's a lot of history between a bunch of people and Chris (Leslie) and Ric (Sanders), not long after that, relatively speaking. I've had the opportunity to play with Richard (Thompson), with Ashley (Hutchings). I've done a lot of work with Richard. And as you know, it sounds like a terrible old cliche, but it is just a really good collection of people who know each other.

Yes, there has been the occasional fall out and someone gets their knickers in a twist. I've definitely been guilty of contributing to that once or twice over the years, where I've done things that have irritated people and they've probably done things that have irritated me. But, Jeez you know, I don't know too many people in any situation in life where they’ve been close to people for fifty years and they haven’t had the occasional fall out! I think the world of these people, you know, the world of all of them, these guys here, and I think the world of Richard, Ashley and everybody that's been in the band.

PB: You were with Richard's touring band for a while as well, right?

DM: A long time. Eighties onwards for a long time with the big band. The incarnation with the big band when Simon and Peggy were in it with the sax players. And then another incarnation for a long time in the nineties with Pete Zorn and Danny Thompson. We made a lot of records with them. So, there’s quite a bit of history goes back with that, with those with Richard and various combinations with him.

PB: At what age did you first start playing?

DM: Well, I started playing piano at six. I just started off the bat and then foolishly made the decision in my early teens that the drums would be easier. Little did I realize! So, I've managed to keep up with both. I have rudimentary keyboard knowledge but Gary Husband hasn't got anything to worry about! But I do have rudimentary knowledge and that helps. It has a big effect on how I play, because I'm not, most of the time, really thinking about the drums. Well, I am thinking about the drums, but they're not at the forefront. I'm thinking about the harmonic content and the lyrics.

PB: So you're thinking about the song rather than the rudiments, perhaps?

DM: Yeah, I don't really think ‘drummy’ too much. I think I'm thinking about the song. And that helps when I produce records too, because I try to look at the larger picture and not think of licks or drum licks or technical stuff. I'm looking at the larger picture, yeah.

PB: Was there a conscious decision to turn professional, or was it just something that happened, perhaps more organically?

DM: Well, back in the day – now I sound like a fully paid-up old fart! – back in the day when I started, you didn't go to university and do a thesis on Madonna lyrics. When I started, if you said you wanted to become a musician, the careers master or the nearest person to it, would probably start going green and banging his or her head against the wall. It wasn't something that you did.

The first job I had when I left school, I was an apprentice piano tuner. And then after that, I got a job in a then famous drum shop in the middle of London. And it's where all the studio players, all the pop and rock stars and all the jazz players went. And I was there for, I think, about a year. I had a great teacher. He was my boss, a wonderful chap by the name of Johnny Richardson. And I learned a lot about the instrument and I learned a lot about music.

But I knew that I wanted to be involved in music and to cut a very long and hopefully not too boring story short, I got offered a job on the Mecca circuit, which was kind of like a strict tempo ballroom thing. And again, long story short, I did that for about four years I think it was. Then I heard about the audition that Fairport were looking for a drummer and I went along. To say that I was the deer in the headlights is an incredible understatement! I knew absolutely nothing about that type of music. I thought folk music was kind of Peter, Paul and Mary and woolly sweaters. I knew nothing. And they were very, very smart people. And I was, like I said, the deer in the headlights, but I must have done something right because they asked me to join. And I can say without exaggeration, once the light bulb started to shine brightly from an aesthetic point of view, in terms of understanding what the band was doing and what it was trying to do and the whole thing with English music and where they were coming from, to say that it had a profound effect on my playing, again, is an understatement.

Prior to being in Fairport, I was over-enamored with people's technical ability. And they gently taught me to step away from that and not just look at prowess, but look at the bigger picture. So that had an effect on my playing. I stopped trying to be a smart ass and tried to be a little bit more sympathetic musically and on the rare occasions I get asked about my drumming, I say, well, I'm way too close to it to be objective, it has to be subjective. But if there's one thing I will say, I'm always trying to be a good accompanist. That's what I think I'm good at. I'm not a technical drummer, but I like to think that I'm getting a handle on being a good accompanist. You're always going to learn something. If your ears are open, even if it's a musical style or someone's approach that you're not particularly crazy for, you're always going to get something out of it.

PB: So you said the light bulb moment came after about six months or so of you being with Fairport, that you became particularly understanding or perhaps enamoured of the sound.

DM: Not so much the sound, the musical approach. When I joined, I didn't really get it, you know, “Get it”, in inverted commas. I was just responding to what was being presented to me and hopefully trying to do something that I thought was appropriate. But on a deeper aesthetic level, when about nine months into the band, when I did get it, that's when things really changed and it had quite an effect on me as a musician.

PB: So when you came to go off with Ashley to do the Albion Band, was it just the fact that the direction on how he was pitching it to you was more immediately interesting or appealing to what you've been doing with Fairport at the time?

DM: I think at that time I became – if memory serves – I think I was getting kind of exasperated with the jigs and reels at a million miles an hour, which was starting to take over a bit. And I think, again, if memory serves, I'd done the Morrison album with Ashley and just fell in love with that. It's a classic case. It's a prime example, I think is the more appropriate term of phrase of converts. When people get converted to something, they go way, way to the right or to the left, no matter what it is. And I'd say, I just want to play really, really straight and I just love this relatively simple music, but I just love how it is. So, me going to the Albion Band was a reaction to that.

And then after a while, not that I didn't want to be in the Albion Band, but then one finds the happy medium. You know, you find that middle ground, but initially it was like I'm fed up with playing jigs and reels at 237 beats a minute. Let's have something with a little bit more space and air around it.

PB: But you went back to Fairport around this time for one album. Was it ‘Rosie’?

DM: I think so, yeah. So many albums, so little time. Or as the phrase goes, so many drummers, so little time.

PB: You were phenomenally busy around this time, especially working with Nick Drake and John Martyn. How did you manage to have a career as a session musician and a career in a band as well?

DM: I just did. There's a misunderstanding that is frequently talked about in Fairport circles. And that's me leaving when we were doing the ‘Rising for the Moon’ album with Glyn Johns. A lot of people thought Glyn and I had a disagreement. We did have a bit of a disagreement, but that wasn't the reason that I left at that time. What was happening was, I loved everybody in the band and Sandy, it looked like Sandy was going to rejoin.

She subsequently didn't, blah, blah, blah but I just felt the band was banging its head against a wall. It didn't seem to be going anywhere. Musically it was good, but I think, again, if memory serves, I was getting like fifty quid a week. Maybe I wasn't going through a good time, but what was happening was it didn't seem like the band was doing very well. As I remember, we had this manager and we got this fantastic world tour. And the world tour consisted of a TV show in Japan, and Sydney Opera House, and a week at the Troubadour in LA. We came back from that, and they said, “Oh by the way, the band owes the travel company twenty grand.” And it was all around that time, and we'd started this album with Glyn, which I knew it was going to be a good album. But at the same time, in parallel, I'm doing all these sessions, and I'm having such a great time, there's no stress, there's no pressure, I'm making great music, and making really good money, as opposed to fifty quid a week with the band. And I thought, I just don't want to do this anymore. It's too stressful, and I love these people, but I just cannot handle this anymore.

Jumping ahead ten or whatever it was years, when Dave Pegg took the reins of the band from the manager, kind of booking agent, it changed completely, and all of a sudden, it got really, really good. And that was the kind of, what I kind of see as, my tier two in the band. I love that period from the mid-80s up to the back end of the 90s. We had a good run there, and it was very enjoyable, the music was good, and we were earning a living. Nobody gets rich, but like I said, around that time of the ‘Rising for the Moon’ album, I was playing with all these fantastic people, and having such a good time. It's the classic musician thing, you walk in, drums are set up, and all you're thinking about is the music, and you're getting paid really well, rather than the stress of being in a band. A lot of people know about the Fairport name, and that's great that they do, but the band never had the kind of success of a Yes, or a Deep Purple, or a Jethro Tull, or anything like that. It's always been a working band, but back then, it just felt like really hard work, and I wasn't enjoying it, and so that's why I split.

PB: Talking of artists that you’ve worked with, it's probably easier to list the names that you haven’t play with. You’ve been on so many iconic albums, really.

DM: I’ve been very fortunate!

PB: Presumably, people hire you as a session musician because they like what you do, they've heard what you do before but I was wondering how much artistic input you get on a track? Does it vary from artist to artist?

DM: Yes. Well, certainly over the last twenty, thirty years, it's got to the point where I'm booked because of what I'll bring. At the same time, I can safely say I never go in with a pre-planned idea. What I do is to try to write out a sketch of the song in terms of the format, but I don't write out drum parts, because I wait and see what happens. These days, you're often going in just by yourself. I go in knowing the material I'm supposed to play and then it's a collaborative thing. Most of the time, if not all the time, people are asking me to do what I do because they know that there’s going to be an approach that they like, but that's not to say that if somebody says, actually, it's not that kind of thing, it's more like this, and I go, okay, how about this? Or, how about this? That's the kind of thing, it's a collaborative effort, but the kind of work that I do, and the kind of sessions that I started to move consciously away from sessions that are sort of totally scripted. I usually say that I have someone in mind that would be far better suited to doing something like that. You might as well program it.

Sometimes in Boston, I say, “Look, I'm going to get a Berkeley student who can probably read better than me and play exactly the beats you want and everything.” So yeah, it's unfortunate in as much as I'm kind of asked for the approach that I'm going to bring, but that's not to say that I walk in with a dogmatic approach and say, okay, this is how it's going to go down. What do you think of this? Is this going to work for you? No? Okay, let's try something else. What about this sound? What about that? It's a collaborative thing.

PB: Have there been any particularly memorable sessions over the years with any particular artist? Any that spring to mind jump out?

DM: Well, there’s a lot. I mean, ‘Mock Tudor’ with Richard was really good. That was the first time I got to work at Capital in LA and that was great. All the sessions I did with Paul (McCartney) and George (Harrison) were good. I learned a lot working with Brian Eno. I learned a lot working with Bill Nelson on the ‘Red Noise’ album. Anytime there's a good artist, they kind of let you get on with it. They might give you some guidance, but they don't say ‘Do that, play this and play that’. I was asked one time if I’d done any production. I said, well, a little bit. I explained that the main thing I've learned is what not to do. When not to play, but how to react, how to interact with other musicians and the artists. If you're not hearing something you like, either move on or in the case of a musician, if you're really not hearing what you're like, you probably asked the wrong person to do it. That's the thing that I really try and work on. If I'm asking an upright bass player or a guitarist or a keyboard player, I've got an idea of how they play and I'm going to try and put them in the right musical situation rather than, - for want of a better cliché – put a square peg in a round hole. If you're looking for a kind of a singer-songwriter thing, you're not going to put a blues rock guy in and vice versa, for example. There are some people that are that fantastic and versatile and can cross through genres. But that's the thing. And it's the same thing working with the artist. You know, if you're not hearing it, and you say, “Okay, let's move on and let's try something else.” In other words, the antithesis of, “What the fuck are you doing!?” I've been on the other end of that. I've been on recording sessions with a producer or the engineer is not quite screaming, but there's tension and it just kills the vibes. And so that's the thing you learn what not to do.

PB: I was reading on your extensive list of credits. And I saw a name that's very familiar to me, Chip Taylor. I just wondered what you've done with Chip before.

DM: I'd only been in Boston about four or five years and he called and said that he had this duo with this great fiddle player called Carrie Rodriguez. And I ended up doing two albums with him. And of course, I said, “Are you the Chip Taylor that wrote this…?!” “Yes!”

PB: Did you produce or play on it?

DM: No, I just played on it and I was very proud of the two albums I played on. He wasn't so easy to work with, but he wasn't awful. He wasn't a pain. He was just a little eccentric but he knew what he wanted. One of the real upshots was I met a fantastic recording engineer who I've gone on to do kind of half a dozen albums with. He’s mixed albums that I've done and he's phenomenal. That was another good thing that came out of that. Huck Bennett is his name. He did the Debra Cowan record. He's just amazing. I love him to death. Gotta get a plug in for him.

PB: Have you got any idea on what your future with Fairport is looking like?

DM: I'm very pleased to say, they’ve asked me to do Cropredy again this coming year. And then we'll see what happens after that, but they function fine as a four piece. I'm hoping if they decide to do any work in the future and they want a drummer, they'll ask me because it's been great, but I'm not expecting it and I'm certainly not assuming it So, we’ll see but, everyone seems to be enjoying this. I certainly am. It's great to be playing with everybody again. And like I said, we grew up together.

PB: Thank you so much for your time, Dave.

Band Links:-

https://www.davemattacks.com/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dave_Mat

Play in YouTube:-

Picture Gallery:-