published: 21 /

6 /

2022

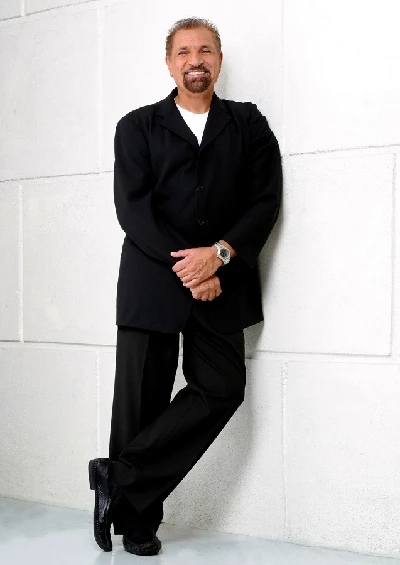

American singer-songwriter-organist Felix Cavaliere, who founded The Rascals in the 1960s, shares his deep knowledge of the music industry, talks about his memoir and more.

Article

It’s “a beautiful morning” alright. Spring has finally replaced Chicago frost and I’m fired up for my talk with Felix Caveliere, whose accomplishments are mind-boggling, to say the least. The native New Yorker, bona fide organist, songwriter and soulful vocalist, who now resides in Nashville, formed The Young Rascals (later changed to The Rascals) in the 1960s with guitarist Gene Cornish, drummer Dino Danelli and singer-songwriter Eddie Brigati. The Rascals produced seven albums, of which Felix co-wrote or wrote a succession of chart toppers, including the poetry-laced ‘A Beautiful Morning’ and the life affirming ‘Groovin’.

Over the years, Felix embraced more personal philosophies in ‘People Got To Be Free’ and expanded his range to include jazz and psychedelic influences.

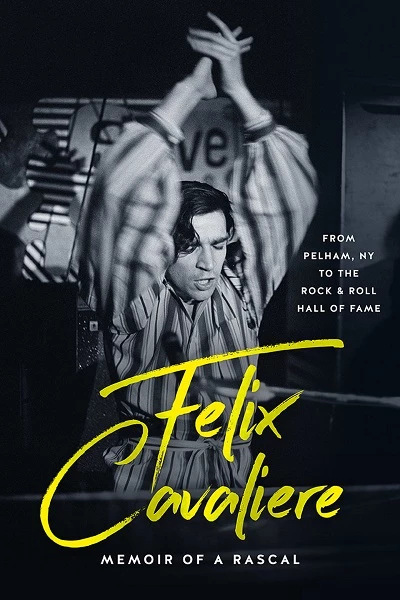

Feiix recently completed ‘Memoirs of a Rascal: From Pelham, NY to the Rock ‘n’ Roll Hall of Fame,’ on which Linda McCartney’s evocative portrait shot of Felix graces the cover. Based on a fifty year-plus knowledge of the industry alone, this book is sure to be illuminating.

In this interview with Pennyblackmusic, Felix unravels early Rascal history, explains the reason behind his memoir and offers sage advice to industry newcomers.

PB: I read that there were no musicians in your family; your father was a dentist. You’re a first-generation Italian American. Italian-American singers have contributed greatly to the American music industry. Did you grow up listening to Bobby Darin, Frank Sinatra, Tony Bennett, Bobby Rydell or Dean Martin?

FELIX CAVALIERE: No, not really. The music that I heard since I was thirteen was classical, pretty much. TV was pretty white-oriented. You didn’t really hear rock ‘n’ roll until the ‘50s and then basically I was pretty immersed in classical until I was about thirteen or fourteen.

PB: When did you start studying piano?

FC: At five. My mother wanted me to be a classical pianist so she enrolled me in this serious school, where I had three piano lessons a week for eight years. She saw some talent and so she tried to develop it.

But I could not create in that realm. I basically had to do what these magnificent composers contrived to put together hundreds of years ago. That was what motivated me to try something that I could create.

PB: In your early years, you performed with Joey Dee and the Starlighters of ‘The Peppermint Twist’ fame. You played the Long Island, New York circuit. Billy Joel played with The Hassels there, too. You developed a life-long relationship with Billy, didn’t you?

FC: Well, you see, we were one of the first American groups to come out during the British Invasion, so to speak. Billy’s a little younger than I am, and so he basically saw us as a milestone as to what could be done in music. He liked the group a lot. So did Bruce Springsteen. We had a really good relationship with the tri-state area: New York, Connecticut and New Jersey.

PB: More recently, you played keyboards in a video in which Billy sang ‘Hey Girl.’

FC: Billy’s amazing and his main instrument is piano. At that time, my main instrument was organ. Billy’s in a class by himself; there’s no question about that.

PB: Performing at The Barge was a turning point in the band’s career.

FC: We had just started in 1964 or 1965. A gentleman came into the place where we were working. He had a very successful discotech in NY called Ondine. He asked us if we’d like to be the house band for a club in The Hamptons. That was, and is, where anyone who could afford to live in The Hamptons, including record executives and movie actors, the hoi polloi, so to speak. That’s where they go in the summer.

So, I knew that it was just a matter of time before we got discovered. If we were worthy, we’d be discovered and that’s exactly what happened.

PB: And you got signed to a record deal in six months. Was that because your band was well--rehearsed and you had great material or was it just luck?

FC: All of the above. But here’s the situation. When I was with Joey Dee, I went to Europe with him. His piano player had quit. And I saw The Beatles over there. They opened up for Joey Dee. And I was able to access what they were doing from a distance. It was total chaos in that room. The audience was hysterical.

I really thought they were primarily a singing group. I didn’t think their musicianship was anything special. It was okay, especially when they did American music. They didn’t have the rhythm. When they did their music, however, that’s when my ears really opened up. “Oh, my god. This is amazing.”

And that’s when I was making the decision whether to go into the music world or not; I was going to college. That’s when I made the decision. If I could get the best musicians that I could find; the best singers that I could find… And that’s what I did.

I went out and found three other people who had been leaders of their band, or a key member of their band. So, it was very strong. Very strong. And I think that made a huge difference. It was also difficult to govern four alpha-males like that. That was our problem.

But as far as the group and the power that that group had; it was a pretty strong group. So, I understand why they liked us; we were a good band.

PB: Like most bands, you started out doing covers, but gradually began co-writing with Eddie Brigati, as well as writing your own material. What was the collaboration process like?

FC: Basically, all the clubs at that time were 21 and over and they demanded covers. They didn’t want to hear originals. They were not interested at all. Their interests, primarily, were that people would come and dance and drink. There was no aesthetic value. That was pretty much in The Village. They were more folk-oriented, like Dylan.

When we started, we hadn’t had a lot of experience writing. At Atlantic, they got us some writers from Motown. We put out, ‘I Ain’t Gonna Eat Out My Heart Anymore.’ The next song, ‘Good Lovin’, was a multi-million seller. The oneness of the group changes a little bit and the group is not so beholden to the record company as the other way around. We started writing.

That’s where I think the good fortune and the luck comes in. That’s not an easy transition. That’s what happened. And all of our peers: The Beatles, The Stones, The Kinks, pretty much all of them, with the exception of The Animals, were writing their own material. So that’s the world we waded into; we had to compete, so we tried to write.

PB: I was sorry to hear that you lost your mother at an early age. According to your memoir, on your search to find answers, you read ‘Autobiography of a Yogi’ and met the author/spiritual leader at a club. Did this meeting offer you some solace?

FC: Absolutely. It was the end of the search, so to speak, because I found what I was looking for. You’re looking for answers, especially when something happens like that, when you lose your mom…

And the music business at the time--my dad told me, if you want to be a musician, fine, but let me explain something; it’s a very slippery slope. Basically, he told me, if you’re a doctor or a pharmacist, you are that until you retire.

Whereas as a musician, you have to keep making hit records. You have to keep being successful or you’re pretty much gone. I know a lot of what they call, ‘one hit wonders,’ and that is the slippery slope I told you about. It’s a really uncomfortable feeling when you’re in your early twenties, and think, I could be gone tomorrow. That causes a lot of consternation and thought.

And then, there was just a genuine interest in what this is all about. Because the people I knew, like George Harrison, were really involved in yoga subjects, so I felt compelled to look into this.

PB: You discuss the impact of The Vietnam War in your memoir, as well.

FC: I didn’t start the band until I alleviated my draft situation. Those were tough days for us. It’s a terrible feeling when you don’t know what you’re going to be doing in the next three years of your life and you have pretty much no choice in the matter. We all went through that and I hope we never go through that again.

But until that happened, I really could not start any endeavour. It was foolish, because you were just going to be whisked away. The interesting thing is I did start the band after my draft status was set in stone. They were not interested in me.

In the beginning, they were choosey. They wanted people that they thought would be good soldiers. With my long hair, I don’t think they thought I was good material. “We’ll call you if there’s a nuclear war.”

I started the band at that point. But all of the other members had to go through this process after the fact. It was really, really emotionally difficult. Going to the draft board was not a pleasant experience. If you want to be a soldier, that’s great. Bless them. But if you don’t, it’s a very trying situation.

PB: Why did you choose this particular time to write your memoir? Was it because you had more non-performance time due to the Covid-19 pandemic?

FC: It’s a combination of reasons. First of all, the original group got together for a Broadway Show and potential tour called ‘Once Upon a Dream’. During that time, there were these press conferences. The four of us would be onstage, queried by reporters. Everyone had a different answer for the same question.

That’s what triggered me. I wondered about world history. Did Custer really lose or win? What is the story here? The story is the last man standing. I didn’t want to believe that, especially in today’s world with that alternative truth. So, I thought it was important to write something down. Because at least I could make sure I was sane, because I could have sworn I was there. It was interesting to me that people had such different stories for the same question.

I had to make some serious decisions about what to put in and what not to put in. I’ve been here for many decades and I realized that The Rascal part of my life was five or six years, the interplay with the group, so how about if I tell my story?

I really will table The Rascal story for another book. It’s like a marriage. Obviously, most marriages start off on a really positive note but a lot of times a marriage ends in a divorce. I really didn’t think people were interested in that part of it. I didn’t put the majority of the oneness on that.

PB: Rascal songs are uniquely arranged. ‘A Beautiful Morning’ begins with what sounds like celestial wind chimes. The concertina in ‘How Can I Be Sure’ is reminiscent of a French cabaret.

Thematically, many songs reflected youthful, romantic realism. The line, “Flying too high can confuse me” in ‘How Can I Be Sure’ reminded us that we didn’t have to know all the answers if we fell in love. The Rascals worked intensively with producer Arif Mardin on many arrangements. In what way did Arif contribute to the sound recordings?

FC: It’s the same as George Martin was to The Beatles. Arif was phenomenal; not only a musical talent, but a wonderful human being. He got his musical education in Turkey.

The Beatles were responsible for ‘How Can I Be Sure.’ If they had not written ‘Michelle’ or ‘Yesterday,’ I don’t think I would have been able to do that. When The Beatles wrote a song, the radio stations didn’t have the option to not play it. They had to play it. So now they opened up a whole new world to all of us to explore.

The rhythm of that is like, 6/8, 3/4. And then, there is that French connotation, which is exactly what Paul was doing. All I had to do was play a riff for Arif and he knew exactly what instrument to put on it. It was a joy working with him and I’ll be thankful for the rest of my life.

PB: ‘Once Upon A Dream,’ held many surprises, including the use of tabla and sitar. Guests included jazz bassist Ron Carter and sax player King Curtis. A reviewer who compared the album to ‘Pet Sounds’ and ‘Sgt. Pepper’ called it “an uncelebrated masterpiece.” Was it overlooked?

FC: I really don’t pay much attention to the rating. There are a lot of products out there that you really shouldn’t put in your kitchen, but if it makes the chart, so to speak, I guess, you should put it in your kitchen.

The public really decides with longevity. You mentioned ‘A Beautiful Morning.’ The number one status in Billboard Magazine is a major obstacle. Basically, what used to happen Is the price goes up for your live performance. It’s always a big deal. Well, ‘A Beautiful Morning’ only made number two. I don’t think it made number one. And the song which was number one, ‘Monday Monday’ has disappeared. So, what does that tell you?

It’s the same thing which I experienced at those press conferences. There’s so much that goes into a number one status in anything. I could go on with college football, college basketball… Number one means somebody put a lot of money into you (laughs). That’s where it’s at. That’s the world we live in.

Longevity. That’s a different story. That song lasts, which it has, and that speaks for itself. We did not get the push behind that for a number of reasons. When ‘Sgt. Pepper’ came out, I looked at that; what an opportunity. That’s where it’s at.

And you mentioned the Italian culture. And the opera is a major part of our music. You had ‘Once Upon A Dream,’ you had ‘Tommy,’ with The Who, turned into a Broadway show. It was magnificent. The record companies really did not want that. They wanted hits. They did not want that continuity of forty-five minutes or an hour. The aesthetic doesn’t exist anymore.

It used to. Labels like RCA Victor or Deutsch Gramophone would have artists such as Stravinsky. They know they’re not going to sell but it’s an honour to have that artist on your label. Do you know what I mean? Those days are gone (laughs).

PB: Regarding 1968’s ‘Freedom Suite,’ the label was wary about ‘People Got to Be Free’ and ‘A Ray of Hope’ stirring up political controversy.

FC: There must be a book of all the groups that were rejected by record executives that turned out to be zillionaires. The Beatles? Decca was the perfect one. They think they know what they’re doing. If they do, they stay on the job. But if they don’t, someone else… (laughs.) Nobody can tell you what a hit is and what’s not a hit.

When I do ‘A Ray of Hope,’ I say, I can write a song without pissing everybody off. I mean, you can’t say what you want and what you believe anymore. There’s nothing in that song that is in any way controversial. But you look at Dixie Chicks, they come out and have a statement and they’re blocked from the radio. What? What is this? If music is not able to emote your feelings, it’s schlock.

So anyway, the record company thought we were treading on water. And we had already treaded on water with our stand to have a black act open for us or be with us onstage. To me, that is so silly because the bottom line is we crossed over on all of our hits. We crossed over on the R & B black stations. I wanted people to know, “You’re welcome here. You’re welcome to come see us.” How can you do that better--put an opening act or put somebody else on that, you know? They were happy, but it caused a lot of difficulty.

PB: And you wrote that material after the Bobby Kennedy assassination?

FC: I was mortified. I really was. When Bobby Kennedy was assassinated, I was seeing a young lady that had been there. When people get involved in a campaign--even in 2016; 2020, all of a sudden somebody wins the primary and somebody kills him.

PB: And it’s crazy that a song meant to galvanize people and give them hope would be considered controversial by the record label.

FC: You would think. I guess, we’re just supposed to make money. You go to church. You hear songs. They’re supposed to inspire you. Our generation; we really believed that. I was brought up with Peter, Paul and Mary; Bob Dylan.

They put their foot in the water and it’s so wonderful because a lot of young minds are being formed. They need to have, at least, that knowledge, that maybe somebody out there is thinking what I’m thinking.

PB: The 1971 double album,’Peaceful World’ celebrates jazz through extended solos and exploratory improvisation. Buzz Feiten, formerly of the Paul Butterfield Blues Band, was a noted guest. This was quite a departure from earlier works. How did Feiten’s guest appearance affect your musical vision at that time?

FC: The transition—when we started with Atlantic Records, it was AM radio. As the years progressed, it was FM radio. Now the playlists were expanding to more than two minutes and thirty seconds. AM radio was pretty strict. If you didn’t have under three minutes, they were going to fade you out, or at the very least,not even play it.

When that changed, the group changed. My ex-partner Eddie quit. He didn’t want to play anymore. He didn’t want to sing anymore. He didn’t want to write anymore. So, he left.

Then, due to extenuating circumstances, our guitar player, Gene, left. So now, I really had to make a decision. And I made a decision to find people that could play, like Buzz Feiten. He was unbelievable; an incredible guitar player. He went from The Rascal Band to Stevie Wonder. He’s really done a lot. He’s still doing it.

So, it was an attempt for me to open up. And it was very difficult for the fans to digest that. Once they get a vision of an artist, they kind of want to keep you in that box. I haven’t found too many boxes that I like to stay in.

PB: That’s because of that resilience.

FC: I think so. That was before CDs. And in Japan, they did a survey. They did a popular vote to take an analogue album and turn it into a CD and ‘Peaceful World’ won.

PB: Again, in 1972, with ‘The Island of Real’ you took on new terrain.

FC: In the olden days, the kings and the princes and the wealthy people would give people like Mozart a place to work and create. And even they would say, I want you to write an opera about my parrot. They provided the income, a place to live. Nowadays, that doesn’t exist. It’s the same; if you want to run for politics, you’d better have a lot of money behind you. Very few people are able to rise about that, but that’s what it’s like.

PB: Beyond making a living as a songwriter, instrumentalist and singer, you’ve worked as a producer. What was it like working with fellow singer-songwriter and keyboardist Laura Nyro?

FC: Wonderful She was the best; a great lady and a very, interesting human being. The eccentricity she had was unique. She was probably the purest artist I’ve ever met. She didn’t have, as far as I was concerned, any monetary desires, just creativity. That’s all that she wanted to do, proven by her songs that other people have taken and made into number one records.

They took songs with words that were controversial or unacceptable to radio. She took them out; made them number one records. She could have taken them out because she’d been told.

For example, ‘Christmas And The Beads of Sweat.’ Someone from the company came up to her, and us, and said, “You know, you can put the word, ‘Christmas’ on the album, and after Christmas is over, they’re going to pull it off the shelf.” Guess what? That was Laura.

PB: After being an all-around entertainer, what did you learn by becoming a producer?

FC: Again, if you watch Arif, he was a real diplomat. He was a tactician. They need people like him in the United Nations. If you’re going to produce an artist, that’s what I wanted to be like.

You can’t do the Phil Spector version. Of course, I’m not Phil Spector, but you have to produce them. This is how they hear it. Let me see if I can bring that out, what you’re talking about. I can bring my experience to create the songs, how you hear it. I definitely learned that from Laura, too, because she wanted to hear what she heard. What she heard in her brain, you’ve got to reproduce that somehow.

PB: The Rascals’ songs have been covered widely. Are there any versions which made you say, ‘”The act really nailed it,” or “What were they thinking?”

FC: Pat Benatar did a great version of ‘You Better Run.’ The Fifth Dimension— ‘People Got To Be Free’ was really nice. Aretha did ‘Groovin’.’ Marvin Gaye covered us as well. It’s not for me to judge whether I like what they do or not. There are versions of ‘How Can I Be Sure’ that are out, and they change it, sure. For the most part, you enjoy it and are honoured when they’re doing your song. That’s how I look at it.

PB: What songs are the younger generation grooving to?

FC: That’s a good question. I don’t know until you try it on them. The younger people, you know, react to the rhythm. If you have the drum really poppin,’ they jump in on that. I hope they do. They’re used to thousands of words with the rap. I think, it’s the message. Hopefully, ‘It’s a Beautiful Morning’ and ‘People Got To Be Free.’ ‘Good Lovin’’ always rocks the house. Do you know what I’m saying? From the rhythmic and musical point of view, rather than the lyrical point of view. You don’t know until you get in front of people. It changes.

Like, right now, ‘People Got To Be Free’ is going to be our biggest solo on the set because people definitely have got to be free.

PB: The brand-new video of ‘A Beautiful Morning’ with brightly blooming blossoms brings out the exuberance of the lyric.

FC: The time that that was written was really a wonderful time. It was the number one record behind ‘Groovin’.’ I say this on stage: “Madly in love. Sun is shining.” Come on. It’s hard to be in a bad mood… And boy, we need some of that today. Let me tell you. We really need that—"it’s gonna be alright.”

PB: You’re touring with Micky Dolenz on the Legends Live Tour. That’s the latest?

FC: That’s the latest. I’ve known Micky for many years. I knew all of the Monkees. They were an interesting group of people from top to bottom. Davy Jones, I worked with in the past. People don’t know his talent as a comedian. He was also talented as an actor.

Peter Tork lived in Connecticut, where I lived for many years. He was quiet and erudite. What I did not know about was the death of Mike Nesmith. If you look into his accomplishments, other than being with The Monkees… Wow, as a songwriter and MTV. He was one of the first to do the Nickelodeon videos. And Micky, of course, he’s a hoot. I saw him right before Mike passed. I hope he retains his insane outlook on life.

I also took advantage of the pandemic to create a new album that will be out, hopefully, in the fall, and the one avenue that I want to continue to work at. I was able to do a few symphonic dates with my music and I’ve got a few of those coming up. That, to me, is the complete circle of where I started.

People who do that, like Frankie Valli, does that all the time with symphonies. He told me, “Man, you’re going to love this.” I’ve done it a few times and that’s where I’m aiming now. To keep working as long as I can; to keep enjoying saying hello to my friends out there.

One of the things we do when we travel is see people that you went to school with, or you grew up with. I just want to keep on keeping on.

PB: How does this work? You’re in the centre and the orchestra embellishes your songs?

FC: Exactly. And I’ve got these phenomenal charts that were put together by one of the ‘Saturday Night Live’ people, Tom Malone. He did the orchestral arrangements. It’s a lot of fun.

PB: Do you have any advice for emerging musicians?

FC: They should not have any illusions about what’s ahead of them. It’s not an easy road. When I used to do seminars for music schools, like at Berklee on the east coast--I just wish people would pay attention to some of the other avenues besides being onstage as singers. For example, video games. These people who make music for video games are multi-millionaires. No one knows their name except the bank.

You can be behind the scenes in movies. You can be behind the scenes in commercials and video games and have a career in music, besides being onstage.

PB: That’s great advice, Felix. Thank you.

Article Links:-

https://www.felixcavalieremusic.com/

https://www.facebook.com/felixcavalier

https://www.twitter.com/felixcavaliere

Band Links:-

https://www.felixcavalieremusic.com/

https://www.facebook.com/felixcavalier

https://twitter.com/FelixCavaliere

Play in YouTube:-

Picture Gallery:-

Photograph by Linda McCartney