In Dreams Begin Responsibilities

-

#4: From Leonard Cohen to Long Covid: Music and Mental Health – Part 1

published: 9 /

6 /

2021

In his regular column ‘In Dreams Begin Responsibilities’, Steve Miles begins to looks at the topical issue of mental health and its effect on music and songs by Leonard Cohen, Suicidal Tendencies and The Smiths.

Article

Many years ago, Tam, my best friend at the time, took me on the long drive to Scotland, from whence he came, to show me around. On the way, as we listened loudly to our favourite music on tape, we found ourselves discussing what music we would still enjoy if the world was everything we would wish it to be. The conclusion we reached was that a lot of our favourite records would cease to be ‘needed’ or enjoyed in a perfect world. Much of what we loved, we concluded, we loved because it helped us to live in this imperfect world - and would no longer be relevant in paradise.

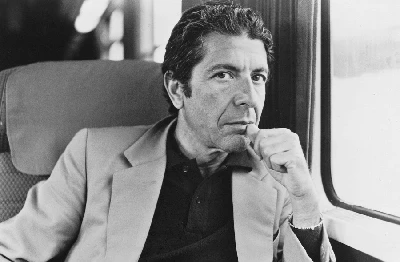

For context, he had in the previous year introduced me to the music of Leonard Cohen, to whom he was a devoted disciple.

Now, both Tam and I felt strongly that Cohen was not at all the ‘depressing’ listen he was so often said to be; on the contrary, he made us feel better in the main. But at the same time we knew that we wouldn’t listen to him as much, if at all, if we were happy all the time. And we knew that he was an acquired taste even in the world as it was.

What does that tell us? The observation still interests me today, and I’m going to explore it here.

One of the most welcome changes in culture in the last thirty years has been the improved understanding of, and empathy towards, mental health issues. And in the main, this has only come about by people being brave enough to be frank about it. Like racial prejudice, sexual preference, or gender identity, the more openly and honestly it’s discussed the better. Of course, we’re not there yet. Glass half full: the nation’s newest princess felt free enough to admit that the media intrusion on her life during her time in the UK was so acute that she “didn’t want to be alive anymore.” What a step forward! Glass half empty: Piers Morgan said, “I don’t believe a word she says,” on national TV in response. There’s clearly some way to go yet, but things are better than they were.

According to one source, a year after the first Covid case, “calls to mental health helplines and prescriptions for antidepressants have reached an all-time high. More than six million people in England alone received antidepressants in the three months to September, part of a wider trend and the highest figure on record.” Meanwhile, many others, including many close to me, have said that music – making it, listening to it, thinking about it – has been their saviour through the pandemic.

So what has music got to say about mental health? And what does mental health have to do with music and musicians?

For the next few issues, this column will be looking at those questions – from songs about loneliness, despair and heartbreak, and how they heal or harm us, to the way music tackles racism, prejudice, growing up and growing old; from singers who have famously taken their own lives, like Ian Curtis and Kurt Cobain, to the way music deals with relationship and body issues.”‘Who was that on the window ledge?/Did he jump or was he pushed?/He left a note which no one read/In desperate hand the note just said/Never turned my back on society/Society turned its back on me/Never tried once to drop out/ I just couldn't get in from the very start.” – ‘Did He Jump?’ from ‘The Curse of Zounds’ by Zounds (1981).

Talking about it, of course, doesn’t make it go away, certainly not in itself. So why is it important to talk about it? More than anything, I think, to remove the stigma, the sense of shame or failure and the secrecy that follows when people feel bad and mixed up in their heads. Because that has a double harm: first, it compounds the sense of low self-worth and darkness in that individual, and secondly because that sense prevents people getting help, finding fellowship, or fully understanding their issues.

Or maybe that’s all wrong and the old fashioned stiff upper lip was better? Maybe snowflake culture is the problem, not people’s minds and emotions. I’ll explore that debate too in the coming issues.

And there’s no more iconic place to start than with Tam’s favourite, Leonard Cohen, and an album where the opening words are, “Well I stepped into an avalanche/It covered up my soul,” and which goes downhill from there...

‘Songs of Love and Hate’ (1971) is sparse and bleak musically, stretching out like the aural equivalent of a deserted, wind-swept beach. Although there are sophisticated arrangements on many of the songs, with dramatically orchestrated strings and horns, and subtle female backing vocals, the album is dominated by Cohen’s voice and guitar. His anxiously flamenco-inspired strum-pluck on the opening ‘Avalanche’ sets a level of often relentless tension, punctuated with thumped lower strings like frustrated exclamation marks. His mournful, contemplative, ever so slightly whiny, younger-man baritone is heavy with reverb and at times he almost seems to refuse to sing, and insist instead on moaning. Cohen’s voice is so much in the forefront of the mix throughout, in that half-spoken half-sung way, that the listener feels more like they are having a conversation with Cohen, or listening to him thinking aloud, than listening to a performance. Even though ‘Diamonds In The Mine’ has a faux-country vibe and ‘Sing Another Song, Boys’ was recorded live at the Isle of Wight Festival, the album’s intimacy remains a keynote - Cohen sings the long ‘la la la’s at the end of the latter like he’s sobbing.

This is the record that gave us one of Cohen’s most celebrated tracks, in ‘Famous Blue Raincoat’, which somewhat cloudily appears to address a man who has had an affair with Cohen’s partner. Although it starts by saying ”I’m writing you now” it’s not fully obvious that it’s in the form of a letter until the very last words –“‘Sincerely, L Cohen” – which are delightfully and incongruously formal after the intimate revelations in the song. The song has a pretty, wistful, gentle melody that perfectly captures the complicated moods of the song: resignation, longing, regret, and gratitude.

‘Famous Blue Raincoat’ is a song that has a lot of sadness in it, but a lot of hope too. The singer sees positives as well as negatives in his own relationship with the “thief” who was intimate with his ‘”ane”. More significantly, he admits to the benefit to Jane of her brief affair with the “gypsy”, best articulated in the deep and potent lines: “Yes, and thanks/For the trouble you took from her eyes/I thought it was there for good/So I never tried.”

There is a world of difference between sadness and depression, and understanding that difference is one of the most important steps in any understanding of mental health. ‘Famous Blue Raincoat’ has sadness in it, but doesn’t speak of depression.

By contrast, the fairly desperate ‘Dress Rehearsal Rag’, the third song on side one, is surely one of Cohen’s bleakest songs, presenting the thoughts of a forlorn man coldly contemplating his failures. He wakes, as the first line tell us, at “four o’clock in the afternoon” (a pattern many depressed people recognise, with either lack of sleep or excessive slumber featuring highly in any symptom list of serious depression) and is soon holding a razor blade. He thinks of a lost love and reflects, “That's a hard one to remember/Yes it makes you clench your fist/And then the veins stand out like highways/All along your wrist” as he gazes unflinchingly into the mirror.

No, this is definitely not music to dance to at a wedding, or to hear piped though the tinny speakers in Morrison’s while you push your trolley past the frozen peas. Cohen was quoted twenty years later as saying that around that time, “absolutely everything was beginning to fall apart around me, and you can hear that on the record. This song in particular is a picture of clinical depression. It’s not a good thing that Cohen felt that way, but it is might be a good thing, in some small way, that he was able to make a record that reflected, exposed and helped to analyse, those feelings.

I say “in some small way” above because one of the strongest and most damaging symptoms of depression is the inability, when depressed, to understand or take perspective on the feeling. ‘Dress Rehearsal Rag’ is a work that never manages to transcend that dark feeling or to offer an angle on it that help either the listener or the author, and it’s partly for that reason that it isn’t, for me, amongst his best work. Musically it’s not one of the strongest songs on the album either, and now that technology allows me to play the songs I want and miss the ones I don’t, I’ll be honest - it very rarely gets played. Is that partly because it offers no hope? Maybe so. ‘Famous Blue Raincoat’ can never be played too much, albeit that it’s “sad”. Maybe that’s because, whereas ‘Dress Rehearsal Rag’ begins at “four o’clock in the afternoon”, ‘Famous Blue Raincoat’ begins “It’s four in the morning”…

What’s really fascinating is that a different version of the song, recorded during the ‘Songs From A Room’ sessions in 1968, and released as a bonus track on the 2007 CD remaster, has a completely different vibe. A few of the words are changed, but the real difference is the performance: it’s a lot faster, in a completely different arrangement, and it’s sung with considerably less despair. If ever you wanted to know why songs are more than poems, comparing those two versions would be a good place to start.

On a live recording for the BBC in 1968, Cohen introduces the song with a kind of melancholy health warning, saying, “I have one of those songs that I have banned for myself. I sing it only on extremely joyous occasions when I know that the landscape can support the despair that I’m about to project into it.2 Not only was he aware of the song’s lack of lyrical redemption but he was also happy to joke about it.

‘Songs of Love and Hate’ is a notoriously sad record, of course, and yet Cohen is grinning on the cover, in a photo taken presumably while he was playing his songs to an audience, while the ‘rag’ in ‘Dress Rehearsal Rag’ refers to a type of music usually thought of as feel-good music, so, as the Canadians (probably) say: go figure.

My friend Tam’s partner was disabled: she had damaged her spine in a fall from a bridge, and they had a young child. They had a lot on their plates, and they both struggled with ‘life’ in many ways, but were always warm, generous and funny with me. We had a great few days in Scotland together, complete lack of money notwithstanding, and I’ve never forgotten how he called sandwiches “pieces”. He recorded all his Leonard Cohen records onto tape for me and I shared my favourites back.

I’m writing this paragraph during the UK’s ‘Mental Health Week’, a national initiative explicitly designed to tackle one of the biggest problems for those suffering mental health issues - the stigma attached to it. When ‘Songs Of Love And Hate’ was released, that lack of understanding or empathy was common for most kinds of deviation from the supposed norm, and just as it was harder to be happily LGBT+ in a time when there was not only a lack of tolerance but often institutionalised prejudice against ‘unconventional’ sexuality, so too it was harder to be happy about being depressed in 1971 - if you know what I mean! There is a therefore an understated, implicit element of apology, that at times hints at shame, in Cohen’s feelings on this record which I think might be less present in a similar record today.

Of course, how anyone responds to a gap between their own values and those of society around them depends on the person themselves. No two people experience emotions and experiences the same way, which is why no-one should ever be the judge of the bravery or cowardice they perceive in others in responding to life’s challenges. For some people, getting out of bed is a harder challenge than it is for someone else to run a marathon. It’s extremely likely that the marathon runner won’t really understand the slugabed, but maybe that’s a good reason to be open and share – because if those feelings are kept secret, those two people will never understand each other.

“To get out of bed/Is more than I can do/If someone must work today/Then let it be you – Television, ‘Careful’ from the album ‘Adventure’ (1978).

Tam and I bonded over our world views and our emotional standpoints; both of us were depressed. We shared that and sharing it made us feel less alone, less wrong. At the time, I thought that it was the world’s fault that I felt alienated and unhappy.

“You know, I used to starve for affection/ I blamed the world, and it could be the world's fault, I suppose - Jonathan Richman and the Modern Lovers, ‘Affection’, from ‘Back In Your Life’ (1979).

I felt that any right thinking person would agree, and any kind and good person ought to feel as I felt. But it turned out that whether it was the world causing it or not, I was not alone: lots of people suffered then and do today from a similar depression, as well as anxiety, paranoia, panic attacks, anorexia, self-harming, stress, trauma, PTSD and many more mental health challenges. But at the time, I didn’t feel I could talk about it openly. When we say ‘mental health’ we think of ill-health don’t we? We don’t think of the ‘health’ in ‘mental health’ as the emotional equivalent of a Gym or a Swim, but the equal of Intensive Care or Casualty instead. Like someone who has put their cigarette out but still stinks of smoke, so ‘mental health’ still carries a stigma even when it’s intended positively.

A generation younger than Cohen, and naturally less retiring and highbrow, the LA born singer and writer Mike Muir felt able to take a much more assertive and even aggressive approach to his darker emotions a decade later, brazenly naming his first band Suicidal Tendencies and writing a host of songs which address similar feelings to those explored by Cohen, but in a way that punches and kicks rather than licks its own wounds.

Their self-titled first album, released in 1983, begins with Muir laughing maniacally and the band just making a noise behind him, before plunging into a ridiculously fast song transparently titled ‘Suicide’s An Alternative’. This has the least romantic call-and-response ever committed to record, as bassist Louiche Mayorga on backing vocals yells in the right channel about all the things that make them “sick” while Muir explains in the left channel just why they are so bad:

“Sick of trying - what's the point/Sick of talking - no one listens/ Sick of listening - it's all lies/ Sick of thinking - just end up confused.”

The song segues into another short track called ‘You’ll Be Sorry’, wherein Muir recounts the protagonist’s vigorous rejection of the devil’s offer to buy his soul over a heavy driving riff and guitarist Grant Estes’ spirited and cliché-free lead. When those opening songs finish, only two minutes and forty-five seconds have transpired, but you’re already out of breath, pumped up and ready to fight your enemies!

The twelve songs on this record put together last barely longer than side two of ‘Songs of Love And Hate’s four songs. That’s not to say that slow or long songs are by definition sadder, but it’s a bullish nervous energy that characterises Muir’s depression on this record: the kind of anger and frustration that makes you hop about from foot to foot and punch walls, rather than the longueur and introspection of Cohen.

While the absence of percussion or drums anywhere on ‘Songs of Love and Hate’ contributes a great deal to the feeling that you are alone with Cohen when you listen to it, by contrast, the rhythm section that powers ‘Suicidal Tendencies’ acts like the souped-up engines in ‘The Fast and The Furious’, while Muir, on vocals, battles valiantly to keep up.

The connection between depression and alienation is strong in music. In the world at large, depression spans all classes, ages, colours and cliques, and can be found across the political spectrum. But in culture, and in music most of all, there is often a much closer link between anti-establishment feeling and unhappiness and mental health issues. ‘Songs of Love and Hate’ is not a strong example of that: there is very little explicit investigation of the world outside of Cohen’s mind on the record. He did, however, explore that more and more as his life went on, with very clear political statements on his later, more accessible and more commercially successful records from 1988’s ‘I’m Your Man’ onwards.

On ‘Suicidal Tendencies’ the link is front and centre from the first second. That first song that listed the things that make Mike Muir feel “sick about himself and his life weren’t simply his failings or his personal relationships, as explored by Cohen. On the contrary, he posits his unhappiness as being at least as much to do with “society” as himself:

“Sick of politics - for the rich/ Sick of power - only oppresses/ Sick of government - full of tyrants/ Sick of school - total brainwash.”

This theme is constantly reinforced across the album. ‘Two-sided Politics’ argues that Muir’s unhappiness and alienation is a function a broken and hostile social system – “I’m not anti-society, society's anti-me/I'm not anti-religion, religion is anti-me” - while ‘Subliminal’ delves into conspiracy theory territory and ‘I Shot Reagan’ (then President of the USA) and ‘Fascist Pig’ speak for themselves.

Muir’s personal pain is not so very different to Cohen’s and he hates himself every bit as much at times, for sure. But much more assertively than Cohen, he posits his mental state as being an inevitable outcome of the world he inhabits as much as of his own failings.

There are two sides to this positioning: firstly, the songs above plainly launch an attack on the aspects of the social system which make the world an unfair, dishonest and violent place to grow up in and live in: Muir is made unhappy by these things. That’s cause of depression number one – the state of the world.

Cause number two is Muir’s own particular upbringing – the institutions and relationships that have shaped him directly and which offer him a future that he doesn’t value:

“Slaving in a factory a different kind of insanity/Feels like I'm locked in a cage/ Working like a maniac, gave myself a heart attack/For a job that pays minimum wage” (‘I Want More’).

And this was never better captured than in their very first single/ closing track on side one, ‘Institutionalised’, one of the album’s longest songs, a masterpiece of teenage alienation and angst.

Kicking off with an iconic, twice-repeated drum pattern, the song instantly settles into a thumping, blood-pumping groove where the bass, drums and rhythm guitar all pound in unison, the dull thud overlaid with the instantly penetrating, spiralling screams of Grant Estes’ lead guitar (he left the band after the album was recorded and the band’s sound was never exactly the same again) that evokes the singer’s pain throughout. Instantly, Muir is talking to us: proper talking, not pretend singing. He is confessing, unloading, unburdening.

Ironically, given my argument throughout this article for the benefits of talking about your issues, Muir’s ire in this song is provoked not by being unable to talk about his depression, but the apparent opposite: his parents’ heavy-handed lack of acceptance of his privacy, or adequate empathy for his moods. He gets “professional help” but this is presented as a dereliction of his parents’ care and a betrayal of his authenticity rather than as a hopeful and healing move.

The song veers manically from those swinging press-ups rhythm where Muir raps over the rhythm to frenzied and frenetic speeded-up parts, where he screams and shouts like a raging inmate while the backing vocals yell “Institutionalised”. Muir protests his “innocence” in these kind-of-choruses and posits the blame at his parents’ and the world’s feet instead:

“I'm not crazy – Institutionalised/ You're the one that's crazy – Institutionalised/ You're driving me crazy – Institutionalised.”

There are a lot of words in the song and for most fans the famous interchange between Muir and his Mum about Pepsi is the highlight, but I’m going to reproduce the final ‘verse’, the infamous family meeting between Muir and his parents below to get to the heart of the song. Yes, to a suburban English observer the band look like stereotypically inane gang members on the record’s cover. Yes, their thrash-metal/punk crossover is incredibly uncool in any and every corner of indie universe. Yes, baseball hats on backwards are as far from Faber&Faber as you can get, and, yes, the band’s name is a major barrier to buying their t-shirts if you’re a sensitive soul, but for my money, it’s a classic song from an underrated (if inconsistent) songwriter, played by a powerful and potent band.

“I was sitting in my room when my mom and my dad came in/And they pulled up a chair and they sat down/They go: Mike, we need to talk to you/And I go: Okay what's the matter?/They go: Me and your mom have been noticing lately that you've been having a lot of problems/And you've been going off for no reason/And we're afraid you're going to hurt somebody/And we're afraid you're going to hurt yourself/So we decided that it would be in your best interest if we put you somewhere/Where you could get the help that you need.”

So far, so good. But in the context of the song, and the context of the album, that’s only half the story. These parental concerns sounds sincere and welcome, but Muir thinks the picture is bigger and makes the case, so to speak, for the defence: is it nature or nurture that feeds his depression? The scientific jury is still out on which contributes most to depression and other forms of mental health, though all agree that it’s a bit of both, but here, faced with the awkward focus on his problems and the emphasis on his failings, Muir makes a strong case for understanding the role that others have played in his issues. He can’t be “fixed” unless the wider problem is addressed, he argues, and he won’t go quietly:

"And I go: Wait, what are you talking about, WE decided?/MY best interests?! How do you know what MY best interest is?/How can you say what MY best interest is?/What are you trying to say, I'M crazy?/When I went to YOUR schools, I went to YOUR churches/I went to YOUR institutional learning facilities?/ So how can you say I'M crazy?"

My friend Tam was a vegan long before it became fashionable, an animal rights activist as well, and lived on benefits. He didn’t work, partly out of hostility to the system and partly because he had to look after his partner. But that left him low on income and social connection. I don’t now recall whether Tam liked The Smiths or not, but the patron saint of alienated young men in the eighties had regularly and wittily captured the contradictions at the heart of Tam’s life, nonetheless.

"I was looking for a job/And then I found a job/And heaven knows I’m miserable now// In my life/ Why do I give valuable time/ To people who don't care if I live or die?" - The Smiths, ‘Heaven Knows I’m Miserable Now’, single (1984). This lively single, which I truly did hear in Asda only yesterday, spookily enough, married broad humour and a little self-mockery to tricky, melancholy chords and exquisite vibrato to create a gentle caricature of outsider gloom, starting with the title itself, a pun on the Sixties single by Sandie Shaw, ‘Heaven Knows I'm Missing Him Now’.

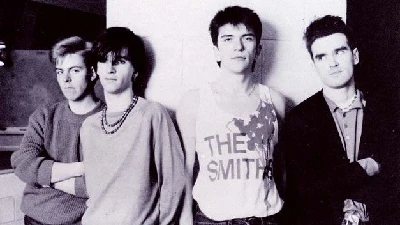

Notwithstanding Morrissey’s awful subsequent degeneration, it would be remiss not to look at The Smiths a little bit more here, not least because. The Smiths’ take on depression was always a lot more arch than the musicians discussed above. Marr’s music drew mostly on the poppier new-wave side of punk, as well as classic songwriting styles from the Sixties’, and therefore lent itself to a mood less introspective than Cohen’s and less angry than Muir’s. Equally, Morrissey’s obsession with popular culture and his stout sense of his desired position within that allowed him to explore his darker feelings with a degree of detachment and irony. He knew precisely the point in the cultural landscape in which he was positioning his feelings. He knew his audience inside out, and he knew how he wanted to be perceived. Sometimes, that self-referential knowing takes all the sting and authenticity out of the song, as with, say, ‘Big Mouth Strikes Again’, ‘Frankly Mr Shankly’ or a good portion of his solo output. But, at his best, when he’s distancing himself from the emotions just enough to be able to laugh at himself, yet still speaking of genuine feelings and situations, he is wonderful: accurately nailing his mental health with a waggish charm. Not only that, but his voice was made for his words – effortlessly emotionally-drenched and lush like a string section.

It’s impossible, for example, to improve on the depiction of loneliness by the simple repetition of almost entirely monosyllabic, everyday words in ‘How Soon Is Now?’ (from the single, ‘William, It Was Really Nothing’, 1985).

“There's a club if you'd like to go/You could meet somebody who really loves you/So you go and you stand on your own/ And you leave on your own/ And you go home and you cry And you want to die.”

The humdrum simplicity of the language makes the crushing disappointment so utterly matter-of-fact. The almost ridiculous repetition of “you” when he clearly means “I”, and the central place of the phrase “on your own” in the verse emphasise the hopelessness and the isolation of the protagonist. Even more powerful, the phrase relates only to the times he’s outside the house – that he’s “on his own” inside his own home is a given, cruelly reinforced by his unsuccessful attempts to find company at the club. Those five ‘and’s in one sentence, echoing an infant’s innocent syntax, ruthlessly reinforce the inevitability of his disappointment. But somehow, there’s hope. Not hope of ending the shyness or of the alienation from everyday life, nor the loneliness or the feelings of being an outsider, but the hope that some sort of pride and clarity will come from owning it, from naming it, and wearing it like a badge. And for making fun of it too. With Johnny Marr’s mutilated harmonic reverb beside him, Morrissey somehow transcends that sadness for the length of the song by doing the exact opposite of hiding from it.

Thrown away as the B Side of the 12” of ‘William, It Was Really Nothing? (1984), ‘How Soon Is Now?’ may well be The Smiths’ most enduring recording, despite not being representative musically of anything before or since. It was an EP that was fresh and brave, before too much time in the studio multi-tracking made Marr too muddy, and before Morrissey became too convinced of his own importance. The EP consisted of an A Side, the whimsical ’William, It Was Really Nothing,’ that dashed along at top speed and only lasted 2:09, and seemed to mean more than it said, and an even briefer B side, ‘Please Please Please Let me Get What I Want’ that was their most sophisticated arrangement yet – the gorgeous mandolin ending propelling the longing into the ether.

’William, It Was Really Nothing’ begins with the lines, “The rain falls hard on a humdrum town/This town has dragged you down” repeated twice, and we are back in familiar territory – didn’t ‘Last Year’s Man’ (track two of ‘Songs Of Love And Hate’) start “The rain falls down on last year's man’” And, odd as it may seem, ‘Please Please Please Let me Get What I Want’ is, in effect, exactly the same sentiment as ‘Institutionalised’, just soppier, shorter and more inward-looking: “See the life I've had/Could make a good man bad.”

Another Smiths’ musical outlier, and again not an album track, is ‘Rubber Ring’, released on the B Side of ‘The Boy with the Thorn in His Side’ in 1985, wherein Morrissey appears to explore the idea of his fanatical listeners breaking away from his spell - or perhaps explores his own emotional growth in the third person, or both - but in doing so, nails the extraordinarily powerful part the a song that speaks to you can have in anyone’s emotional life.

“But don't forget the songs/ That made you cry/ And the songs that saved your life/ Yes, you're older now/ And you're a clever swine/ But they were the only ones who ever stood by you.”

It’s almost as if a relationship has ended, with echoes of ‘Famous Blue Raincoat,’ but instead of physicality between two bodies, there was the communion of vinyl, maker and listener. The bond of singer and song not sex. For the lonely, those to whom ‘How Soon Is Now?’ speaks, it’s likely that songs or films or books have indeed filled the spaces others will have filled by relationships.

And if you can’t talk to your neighbours, or your schoolfriends, or your workmates about your feelings, you look for validation or consolation in art – in music and in literature, TV and film.

“When you lay in awe/On the bedroom floor” it was with a 7” single, not another person’s hand, in yours. But the longing and the love was just as strong, Morrissey tells us, and the value and integrity of the relationship no less authentic or valuable, or less ‘impassionate’ (sic).

After I’d known him for quite a while, I found out that Tam’s partner had jumped, not fallen, from the bridge that left her legs permanently damaged. At the time, this was deeply sensitive information. It probably still is. Tam was very uncomfortable sharing it, his partner never acknowledged it, and even now, I have changed his name to protect their confidentiality.

There is no vaccine to protect our mental health against the consequences of the pandemic or anything else. But there are songs. And that, for now, will do.

Article Links:-

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=H2VJhd

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AhVW0v

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JHiRyu

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LoF_a0

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hnpILI

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AN8kzl

Play in YouTube:-

Picture Gallery:-