published: 14 /

2 /

2021

Guitarist Joanna Connor speaks to Lisa Torem about her new Joe Bonamassa-produced album, ‘4801 South Indiana Avenue’, the Chicago club scene and her blueprint for balancing artistic work and family.

Article

After Brooklyn-native, singer/guitarist Joanna Connor made Chicago her home in the early 1980s, she set her career plan in motion, shredding at the blues-capital’s infamous clubs, and mingling with the “Windy City” crème de le crème.

After setting down roots as rhythm guitarist with Dion Peyton, she formed her own band. Her ten-thousand hours included playing the Kingston Mines, and festivals, and after just a couple of years, the band got signed by Blind Pig Records.

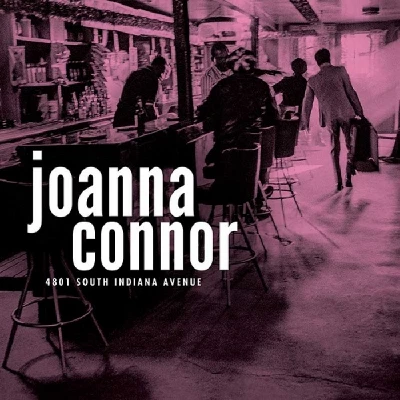

Fast forward to the release of ‘4801 South Indiana Avenue,’ which was produced by American guitarist Joe Bonamassa and guitarist Josh Smith on KTBA Records (Keeping the Blues Alive). This blues-drenched project even pays a visual tribute to Chicago blues history, as the cover shows the inside of Theresa’s, a defunct, but iconic venue. Both Bonamassa and Smith play on every one of the ten-tracks, and in addition, Bonamassa contributed solos on ‘Part Time Love’ and ‘It’s My Time’,

Joanna Connor’s discography is diverse, but on ‘4801 South Indiana Avenue’ the blues are highlighted and the personnel, which is top-notch, includes session musicians plus former Stevie Ray Vaughan keyboardist Reese Wynans, bassist Calvin Turner, drummer /percussionist Lemar Carter and horn players: trumpeters Steve Patrick, Mark Douthit and trombonist Barry Green. Singer Jimmy Hall added warm backing vocals to ‘Destination’.

Joanna Connor talked to Pennyblackmusic about balancing a career and family, perfecting her craft and working with Joe Bonamassa on this unique project.

PB: Congratulationss on your new record. What are your recollections of the 1980s Chicago Blues scene? You were a rare breed; a female electric guitarist. Was that an issue?

JC: It depended on the person, whether it was another musician, a club owner, whatever. Everybody had their own approach; their own opinions, their own reactions. I would say it was seventy-five percent positive, twenty-five percent negative.

There was still a lot of sexism going on, whatever. I was young. There was ageism. I was a wookie. Some were willing to mentor me, but I wasn’t looking for anybody to treat me with kid gloves.

But it was totally one of the best times for music. Muddy Waters, Howling Wolf and a few others weren’t there, but when I got there, there were so many of the greats still around; still playing, and I had that great opportunity to play with many of them. It was an important and wonderful time in the Chicago Blues Scene.

PB: How would you describe your journey to becoming a guitarist? Did it involve playing with your peers, dropping the needle on a record and emulating a solo, taking formal music lessons? Or did you practice in a room by yourself for hours?

JC: Probably all of the above. What really pushed my playing forward rapidly was being out in the clubs, watching and/or jamming and then getting in bands. It’s kind of like a crash course. I’ll put in an analogy: you’re on a basketball team; practicing is one thing, but the game is a whole other.

It’s the same with music--when you’re actually performing, and in the fire you really have to give it your all. It puts you on the track to getting much better or really falling to the wayside (laughs).

PB: On a video, you were playing ‘The Magic Sam Boogie’ and you said to the crowd: “You guys are setting the standards for audiences everywhere.” Your fans feel at home with you. With the pandemic, I’m sure you miss them and the feeling is mutual. What would you say if you could communicate with your fans right now?

JC: Oh man, it has been so difficult for me. When I do play a live stream, of whatever, it feels so unusual. It just kind of puts me at ease, and I would just say to the audience how much I just miss them. I just miss the reciprocal energy that goes on between performers and the audience. I’m not looking for them to worship me, I’m looking for them to enjoy it so much that they let go as much as we let go.

PB: You’ve played with bassist Lance Lewis and drummer Cameron Lewis as your rhythm section for a long time. But in the studio, you were also playing with virtuosic keyboardist Reese Wynans, another melodic instrumentalist. Was that a different kind of challenge?

JC: I’m sure it wasn’t a challenge for Reese. He played with Stevie Ray Vaughan and the Allman Brothers and now Joe Bonamassa. He did give me a great compliment when I first met him. He said, ‘’You’re a bad-ass.’ So that made me feel fantastic.

It was totally inspiring to play with people like that and what made it even better was that every musician had such pedigree and history and chops and everything. But every one of them was super down-to-earth and very flexible and very giving in terms of musicality. So, it was pretty marvellous.

PB: The songs you covered on the album were all written by men. Did the lyrics immediately speak to you? You’re a songwriter, too…

JC: I’m kind of used to that because so much of the material that I do is either written by or covered by men. It’s something that I’ve been doing for decades so that wasn’t a problem. Also, I write songs but it’s not something that’s my primary focus as an artist; like, I need to write a song today.

For some people, that really is something that’s important for their artistic process. For me, it’s like, oh, I have to do an album, let me write a song. It’s very rare that I put that kind of energy into that, so I consider myself more of a player, first; a performer, second.

My thing is living for the moment and actually improvising and being in a musical situation, so that’s the primary thing that I latch on to.

PB: Joe Bonamassa seemed to be struck by your immediacy. Can you talk about “being in the moment?” What happens internally as you play? Are you able to think ahead?

JC: I try to analyse how my brain is actually working. It’s a funny thing. It’s kind of like, I’m almost split into three different ways. I’m singing and playing, so that’s splitting my brain in two and then, I’m also slightly thinking ahead in Nano-seconds, as to what I’m about to play, but it’s such a small glitch of time that, yes, I’m in the present, but yes, I’m also a split-second ahead because that’s kind of how you need to be when you’re improvising, and you, kind of, are anticipating.

PB: You’re a time traveller.

JC: A little bit (laughs).

PB: The closer, ‘It’s My Time’ felt like the most autobiographical tune on the album. And stylistically, it was also quite different from the other tracks.

JC: Josh Smith and I, and Joe, all got together at Joe’s place before we went in the studio and we went through all the tunes; well, they picked a lot of them and then got my approval and a lot of them were by the blues greats, but then Josh said, “I’ve got this song I’ve written for Joanna. We really like it.” Of course, it was just Josh on guitar, so it sounded different.

And then when we recorded the musical tracks, Joe was like, “I like the chorus, but Joanna, I’d like you to make this more personal and tell your story,” so I rewrote the words for the most part. There were a few phrases left over and I literally wrote it in the studio and Joe read it and said, yeah, it was good, and it was his idea for me to do the spoken word thing. I’ve done lot of different styles of music anyway, and, if you listen to my other albums, they’re a little bit all over the map.

You know, sliding from some hard-core blues thing to that; if you come to my show, any given time, I don’t play with a set list. You might say, oh, she just played this hardcore rock blues thing and now, she’s playing jazz (laughs). That’s kind of very typical for me.

PB: The song reminded me of ‘Leader of the Pack’ or ‘The End of the World’—it was contemporary and personal, but simultaneously, a trip back to another era.

JC: Thank you.

PB: So, your new album is predominately slide-guitar based. Who are your slide-guitar heroes? And how did you learn this skill?

PB: I had two periods in my life where I actually took guitar lessons. One was when I was seven-years-old until nine. It evolved into classical guitar.

The second period of time was between fourteen and fifteen, when I took acoustic guitar and learned fingerstyle, and ragtime and Delta Blues and Piedmont Blues and then I met Ron Johnson, where I grew up in Massachusetts.

He was this great slide-player and he loved Ry Cooder. He said, “I want you to learn the slide,” and I said, “Okay, I’m all for it.” I didn’t know what I was getting myself into. I’d heard it, but I’d never paid that much attention to it.

Ron was meticulous with me and very, very stern. I respected him and loved him so it didn’t matter how hardcore he was. His teaching really set a great foundation for me as far as technique. So, I feel like I was really blessed with that.

With slide, you’re dealing with such small measurements in terms of accuracy and delicacy. I mean, all of guitar is like dealing in a small world. This is even smaller in terms of measurement and touch.

So, once you get past that training period, it gets a little different, and then it really opens up a lot of fun because it’s not as physically demanding as regular guitar playing, as far as chording and soloing and stuff. But it drives a lot of guitar players crazy, a lot of great players that I know say, “Oh, I just can’t do this” because it’s such a different way of playing. But it was a fortunate accident (laughs).

Not only being a female guitarist, especially coming up, you know, a while ago before there were many that we knew of, but being a slide guitarist separated me from the pack.

PB: ‘For the Love of a Man’ was a tribute to Albert King, Freddie King and BB King and ‘Please Help’ referenced Hound Dog Taylor. Were you thinking about their playing styles when you came up with your parts or was it more about emotionally investing yourself in the material?

JC: Well, it was a combination of kind of knowing those artists and their styles; but also digging down into myself and being in the moment; kind of like a guideline; an approach. A lot of times, Joe would say, I want you to play this, like, really raw, or when we did, ‘it’s My Time,’ let’s do it like Ry Cooder, but be a little subtler.

He was completely hands-on on every aspect of the record, so he was guiding me through it, but that was fine with me. We really connected in every way which was fortunate.

PB: On, ‘I Feel So Good,’ you hold on to that first gorgeous note with your deep contralto and it’s stunning. You began your career as a singer, but you claim that Joe Bonamassa pushed you to your limits. How so?

JC: The funny part about singing the blues, is that, as a white person, you want to be authentic, but you don’t want to be derivative. You want to pay tribute, but you don’t want to be mimicking. You have to find your spot.

I’m not Southern. A lot of the more successful blues singers are from the South, not generally from the North, and me being a girl from the Northeast, the whole combination; it’s a little difficult to pull it off, because if you don’t sing blues with feeling and a certain tone in your voice, etc., it’s okay, but it doesn’t feel like it really fits the genre.

So, I always had that battle. I always knew that I had a pretty powerful voice. And through the years, it’s gotten much more husky. I didn’t used to have a husky voice, but after years of singing in the blues clubs all night long I definitely weathered the instrument, but maybe in a good sense, and also, I never smoked or anything, but my voice dropped a lot, like if you hear early records. it sounds like me before I hit puberty.

But Joe, he’s a singer. So, sometimes he’d sing parts to me; how he heard it, and I would sing it back to him. He’d say,”‘Really push this note” or “Give it some kind of cadence,” or “Give it this kind of rhythm,” or “Just kind of speak it,” so he would guide me. He really had me singing as hard as I could.

I wasn’t really sure: “Was that the right way to do it? Will I sound like a shouter and have no subtlety?” But on that song, ‘I Feel So Good,’ I probably had the loudest, roughest vocal on the whole album. And that note—I was always pretty good at holding really long notes. Joe was like, “Why don’t you hold it this long?” I said, “Wooh, okay, let’s give this a go” and it worked.

PB: Did Joe Bonamassa use a specific mic placement?

JC: I can’t tell you. I’m so bad with that aspect, but I think a couple of times, he used two mics at the same time. On that song, he had it kind of overdriven, like naturally, so it was a little distorted; that’s on purpose, but it would be best to ask him or the engineers (laughs).

PB: He came into the studio with a philosophy. He wanted to use vintage amps and minimize the use of effects.

JC: That was a new world for me. I love my effects; I don’t have a ton, but I depend on them. I have recorded without effects, but usually for something jazzy or folky on the acoustic. That would be okay, but nothing like straight-up blues; I hardly ever do that.

But he came in. I had my pedals. He said, no, no, we’re not going to use those. Oh, boy. But he had this amp. It was an old Fender 55 Deluxe. Of course, it was his. Later, I said, “Okay, this does sound good.” But that was definitely a new approach. I’d never done a whole record without any effects pedals at all. That makes it even more authentic.

But we didn’t want to be authentic just for the sake of being authentic. Some people in the blues world, they follow a certain guideline. It has to be this; you only do that. It sounds tight. I think the record has the authenticity but it sounds alive, it sounds like it’s happening now. We’re paying tribute, but we’re not being in a museum. We’re breathing life into it.

PB: On ‘It’s My Time,’ you and Joe launch into a slide excursion. Can we get a play-by-play?

JC: Joe played rhythm guitar on the whole record. I was like, “Joe, would you like to play a solo?” He’s like, “Would you like me to?” I said, “Yes, I’d like you to…” So, he came up with that one, he doesn’t consider himself a good slide player. I think he’s a great slide player.

I started off and then he comes in. You can hear the difference in the tone. I do the first solo. He does the second and I come back. He said, “Let’s do a little Ry Cooder thing. Let’s be a little subtler.” So, that’s what we did.

That was the only solo actually overdubbed. All the guitar is stuff we did live, and really the only thing we overdubbed was the vocals, the horns, and the tambourines, because the drummer couldn’t play the drums and the tambourine at the same time. And some background vocals. Everything else was live.

Calvin did the horn arrangements. He was sitting there, while we were having lunch, writing charts. Wow, look at this guy. I think they just hired some people they knew, but they were Nashville session horn players. They came in with charts and they were in and out within an hour-and-a half or something.

PB: Keith Richards seems to have been pretty happy being a rhythm guitarist all these years. What made you move from playing rhythm to lead?

JC: I just felt incomplete. I was a really good rhythm player. I think I still am. I think that’s the best of what I do. So many people, they don’t pay as much attention or dedication to that aspect of their playing. To me, it makes the music incredibly interesting.

My final thing is that I’d love to become a really proficient jazz guitarist. There’s always another level to what you do to be well-rounded and as proficient as you can be.

PB: You’ve accomplished a lot in your career, and even raised kids as a single parent. So, what’s the blueprint?

JC: I don’t know if you’d want to live my life. I feel like the buffalo in the snowstorm. I put my head down and went through it. I never doubted myself; I always knew what I wanted musically, and the older I got I could care less about making it, quote unquote, and more about making great music and enjoying what I do.

Because the business end of it could suck you dry. Travellng all the time isn’t as wonderful after seventeen years (laughs). You’d think it would be, although I do miss it now. But I would say, the blueprint is to be true to yourself; find your own voice. Yes, image is Important, but talent is the ultimate thing, and dedication. Never being satisfied with what you do, so always try to improve yourself as a musician or as a singer.

And in terms of having a family… It’s all possible. But I didn’t live that lifestyle of a musician, per se. I called it; I went to work. I did my job. And I was home with my kids. So, literally, very rarely did I ever go out other than when I played.

And also, in my house—it’s funny. I was in a commercial. They’re like, “I thought you’d have music stuff hanging up”’ I never did that. I didn’t want it to be a shrine to myself. I never hung anything up in the house. My kids were both athletes, so all of their trophies are there. I made it about them.

It’s kind of like, there were two different people. There was mom and there was the musician. That’s what kind of worked for me. They loved what I did. They were proud of me, but I wanted to give them the space to be their own people.

A lot of people had no idea I was a musician, ever. I’d come to the games and they’d say, “You do that.” “Yeah, that’s what I do.”

PB: What are you looking forward to now?

JC: I just spoke with Joe. We had a lot of plans. The album was done last February before the pandemic. We had no clue this was going to happen, obviously. He said, we’ve got to release it. It will be a year.

Sometime in April, we are planning, using my band in Chicago, with me and Joe and special guests, to do a livestream, maybe pay-per-view situation. So, that’s going to happen. I have a few shows possible in May in a couple of other states.

We have no idea what’s going to happen. Festivals keep getting cancelled for next year, but Joe says he definitely has a few more projects in mind for me. We’re going to continue down this road together. I think we make a great team.

He, himself, has done so many different styles of music; so many types of blues and stuff. I think there’s a lot we can do together. So, that’s definitely going to happen.

Our band, we’re just sitting there and waiting until we can go back and do what we can do, like all musicians right now.

PB: Regarding audiences, worldwide. Who appreciates you the most?

JC: On any given night, who knows? With Kingston Mines in Chicago, some nights, it was the greatest. Some nights, it’s just whatever. You never know with the audience. The old cliché: I would say European audiences are much more appreciative of American music. We have it in our backyard in all parts of America. We invented most of this stuff (laughs). Not that we take it for granted, but it’s not as special.

But over there, as much as there’s so many fantastic musicians in England, they still don’t have the feel and the culture that goes along with American music, particularly blues and blues-rock. They’re hungry for it.

And in Europe, too, you’re treated as more of an artist. If you play a club, you’ll never play more than two sets a night; you’re usually done by eleven at night. You’re not out there selling alcohol. There are no televisions in the clubs. It’s more about the artists.

But in most of Europe, that’s how it is for all different types of artists. Artists are more valued there. Not that people in America don’t love it, but the whole culture here is a little, I don’t know, it’s American culture.

PB: You’ve jammed with some heavies.

JC: I don’t remember every song we played. I was at the Kingston Mines. I was playing with Dion Peyton. It was a Thursday night. And on Thursday, there was only one band all night. So, we played many sets with as many breaks as we could. Usually, we’d have people coming up to jam; you’ve got to fill in the time. So, I was on a break and I went to the dressing room. Dion said, “Joanna, I’m going to have you play with this English guy. He’s going to play my guitar.”

“English guy?” Whatever. There was this guy from Atlantic Records. He was a fan of Dion’s. He was from Chicago. He said, “Joanna, I want you to meet someone.” I go over and he says, “This is Jimmy.”

Of course, I recognized him. You could have knocked me over with a feather. He’s like, “Yeah, he’s going to come up and jam with you.” Then, we hugged. Jimmy Page was a super-sweet guy. Very humble. Very kind.

So, we got up to play and so did Sugar Blue and Valerie Wellington. And Frank Pellegrino playing keyboards with our bass player and drummer. That was our jam, and as soon as we started to play, literally, by two in the morning, people started running towards the stage. I can still see that. Ah… It was like an onslaught of humans.

We did five or six songs and then we took a break. He gave me an autograph, which I frickin’ lost, which I could just cry. And he said, “If you keep playing slide like that, I’ll be out of business.” So, he was such a nice dude.

It kills me because it was in the days before cell phones, so there’s no recordings of it.

PB: You’ve jammed with Buddy Guy.

JC: Many times. I was in the house band at the Checkerboard when he owned it. For about a year, we played Fridays and Saturdays with Dion. We played our sets, but we always had a special guest artist. And sometimes, it was Buddy Guy. And moving forward, I’d open up shows for him in Europe. Whenever he plays Legends now, he doesn’t play guitar, but he always sings with the bands when he’s there. So, I’ve known Buddy a long time.

PB: Joanna, if you could live in any other era…

JC: The Roaring Twenties. I’m just fascinated with the whole revolution of culture. I love jazz. I would have loved to have seen the birth of jazz taking place or really original blues stuff, something about that era that just intrigues me; the fashion and the cars; everything.

That, or the sixties, which I was alive in, but was a little too young for…

PB: If you could describe Joe Bonamassa…

JC: I would say he’s a genius, seriously, down-to-earth, with a great sense-of-humour, but very dry. Joe’s a fantastic musician, a master guitarist and very kind; very straight-forward. He is who he is; he says what he says. There’s no pretence.

He was in the spotlight as a kid and he’s just been such an amazing musician for so long. I think, people mistake him: oh, he’s cold, oh, he’s a poser. That’s not him at all. And he’s a fantastic businessman. To combine being a great artist and a great businessman, that’s a rare combination.

PB: Thank you.

Top photo by Maryam Wilcher and other photos by Allison Morgan

Band Links:-

http://joannaconnor.com

https://www.facebook.com/joannaconnorb

https://twitter.com/TheJoannaConnor

Play in YouTube:-

Have a Listen:-

Picture Gallery:-