published: 31 /

10 /

2017

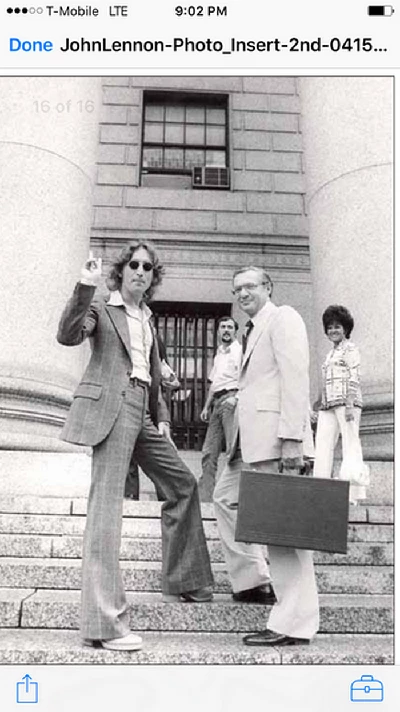

Leon Wildes, author of 'John Lennon vs the USA', immigration attorney and winner of this groundbreaking case, talks about working with Lennon and Yoko Ono, legal challenges and the effects on posterity.

Article

Mr. Leon Wildes, founder and senior partner of the Wildes & Weinberg law firm, New York City, and the National President of the American Immigration Lawyers Association in 1970, is a prolific author and presenter, and is noted for successfully representing John Lennon and Yoko Ono in deportation proceedings from 1972-1976.

In his most recent book, 'John Lennon vs. the USA.: The Inside Story of the Most Bitterly Contested and Influential Deportation Case in United States History', he chronicled his pioneering role in these proceedings, which came about during President Richard Nixon’s reign, when Lennon, who played an active role in anti-war activities, was perceived as a threat to the U.S. government.

Wildes also appeared in the 2006 documentary, 'The U.S. vs. John Lennon', has discussed immigration issues on major American talk shows, and taught immigration law at Cardozo College for more than 33 years.

In August he attended The Fest for Beatles Fans, Chicago, where he and his son and legal partner Michael Wildes discussed the book and warmly responded to queries from a legion of Lennon/Beatles fans. In his first Pennyblackmusic interview, he talks about his impressions of the late John Lennon and artist Yoko Ono; the legal strategies he used to win this landmark case; and finally, the lasting effects.

First Impressions

On January 14, 1972, Leon Wildes first became acquainted with the legal problems of John Lennon and Yoko Ono Lennon through a legal colleague named Alan Kahn. He met with Kahn and Lennon’s legal advisor Allen Klein at Apple Records, and whilst driving to meet the Lennons in Greenwich Village was briefed on John and Yoko’s visa problems.

Here he elaborates on his first impressions of the couple and the nature of their visa issues.

"John Lennon and Yoko Ono came on visitor’s visas for a legitimate, temporary purpose in the United States and the purpose was to try to nail down Yoko’s former husband who had been hiding their child out. The way I heard it, he (Tony Cox)had picked her up for a visit one day and never brought her back. He had been involved in some kind of religious commune and they didn’t even think that he called the child, Kyoko, by her real name. They had been hiding out and they had trekked all through Europe, trying to catch him, but every time they got to a town, their name was so recognized that it was easy for him to find out that they had come, and to scoot off, so that was a kind of hardship that they had and I was very impressed with the fact that it was not considered by this couple to be only Yoko’s problem. John thought of this child as his child and he really was very concerned about getting custody or visitation with the child.”

The Immigration Service and 'Non Priority Cases'

When Wildes did further research on the case, he determined that John Lennon’s immigration problems appear to have started because of his connection with anti-war activist John Sinclair. Radicals Jerry Rubin, Abbie Hoffman and Black Panther Party leader Bobby Seale had encouraged Lennon to perform at the John Sinclair Freedom Rally on December 10, 1971 in Michigan. FBI agents were in attendance and were documenting Lennon’s song lyrics. (Sinclair had been given a lengthy prison sentence for possession of marijuana and was considered, by the youth movement, to be a political prisoner.)

In Chapter 1 of 'John Lennon vs. the USA.', he writes, “In coming to the defense of John Sinclair, John Lennon and Yoko Ono had made some very dangerous political enemies.” Pennyblackmusic asked Mr. Wildes to comment on the relationship between John Lennon and John Sinclair.

PB: Some historians have suggested that Lennon was used by the Left. What made him so sympathetic to John Sinclair’s cause?

LW: I think that he felt very sad for what happened to John Sinclair — a ten or eleven-year sentence for possession of marijuana is outrageous. I’d never heard of anything like that and I think that he was carried away with it.

John Sinclair had already been in prison for two years when they had that get-together for his benefit, and John had written a song for it. It was very important to him because he hadn’t performed for the previous five years. The Beatles had broken up as of that point and he was on his own, and so he came with Yoko and they sang together a song that he had composed for the occasion and he really committed himself to it.

That day of the concert, it was 3 am in the morning when they came up on the stage to perform. The concert hall held 15,000 people and there wasn’t a seat in the place. Imagine how many other people came out for the same reason, to show their feelings for John Sinclair, and it was unusual to see a Beatle there.

Wildes determined that the U.S. Immigration Service seemed particularly eager to arrange for the deportation of Lennon and Ono. He then asked the Immigration Service employees why so much emphasis seemed to be place on deporting a world famous artist when such a deportation would seem to be a 'non-priority case'.

PB: How did the F.O.I.A. address the issue of 'non-priority cases'?

LW: I contacted Immigration Services and said, ‘Why are you doing this to John Lennon?’ They had to respond and the response basically was the response from the District Director of New York District, Sol Marks. He said, 'I have no authority not to enforce the law. I have no discretion in the matter.' He’d been asked this on so many different television programmes and his answer was uniform.

Essentially we needed to prove what I had surmised from my history in immigration law, that Yoko’s case was one where the government had not enforced the law. You can’t take a paraplegic and put him on a plane and have TV watching him, as they send him back to his country. Whatever it was, I surmised that there were such cases and eventually I was able to prove that.

One day they delivered 1,843 immigration cases to my office where the people were still in the United States, and even though some of them had gone under proceedings, none of them had been removed. John had asked me to study those cases because the government had never acknowledged that they had had that authority. So what he wanted to do was to find out if the other aliens and other immigration lawyers had the authority to show in their case that what the government was saying was untrue, and that there are such cases, and as a result they shouldn’t be able to build a foundation on those cases; I was sure there would be some cases where some people would not be removed. That is what we did.

It was interesting that what the judge said was that I’m afraid I’m going to have to uphold the paperwork myself. The government was not going to allow John Lennon to run through their cases to see what he could find. So they just turned it over to us. As a result of that and the question that John asked, I published law review articles with hundreds of footnotes and so on. All the cases involving drugs were much more serious than John’s. There were people there with every conceivable drug, revolving around selling it and promoting it.

So we were able to enable a lot of people and their lawyers to study the cases and I explained it to them and I showed them what they could look for and how they should do it. I had many, many conversations with lawyers all over the country, such as the Association of Immigration Lawyers, and so I was known for that case. Many of them called me personally to review the facts of their situation and I was giving advice on their cases.

The Case and 'Third Preference'

Wildes then turned to the other side of the case to see why John Lennon should be allowed to stay in the United States and found out that there was an unspoken 'third preference' in immigration practice to favour allowing artists and other creative people who were deemed to contribute to the community to get residency.

PB: How was the 'third preference' exception under U.S. immigration practices used in terms of proving discrimination against Lennon?

LW: “The 'third preference' was, at the time, the top preference for outstanding people in the arts and sciences. They didn’t have to be sponsored by an employer; they didn’t have to be sponsored by a close relative. It was just based upon documentation of their outstanding abilities in specific fields.

And, of course, here I had two of the most outstanding artists in the world, and so when I filed those papers I was very disappointed that I didn’t even receive a receipt for it and they never acknowledged that they had it, and it was several months already and under the old system, I noticed that they had asked the advisory department for their opinion about the case being adjudicated, but there was nothing about it.

So before I attended the hearing, I had the District Director of New York seal off all of the files and he showed me what he claimed to be all of the files, but they weren’t. They had never even shown me anything about Yoko’s file. She had spent half of her life in the United States, in one status or another, as a student, and so on.

Because of the marriage to her first husband, who was an American citizen, she had gotten permanent residence. They had never even shown me the file. There’s never been a question that if they had shown me that file, that would have been established.

In reading 'John Lennon vs. the USA', Pennyblackmusic was intrigued by the amount of time Wildes spends generously praising his courtroom opponents during the highly contentious proceedings. As he explained, there were reasons for his praise of his opponents, in particular the lawyer for the District Immigration Office, Vinnie Schiano.

Courtroom Relations

PB: In your book, you often praise the background of courtroom opponents. Is this part of your general philosophy in dealing with difficult situations?

LW: I don’t know about that. Vincent Schiano happened to be a man whom I respected. I knew him for many years. I knew him when he’d been involved in trying to get Nazis out of the United States, who came after the war, lying about their history during the Nazi period. They managed to get in by lying. He would not accept those cases.

He would advise the government to deport those people and I respected that. As a result, I always got along with him and we respected one another.

I tell the story in the book about when John and Yoko and I originally came to his office. First of all, to get through the immigration door, I came about an hour early. I wanted them to know that they didn’t have to fear the government, that this was a straight guy doing his job and that was the time that he said to me, ‘Leon, I don’t think they realize that I’m the prosecuting lawyer in their case.’

So I said to John, ‘Vinnie, here, is the prosecuting lawyer in your case.’ Vinnie told him, ‘I respect and love your musical work, so you shouldn’t feel in any kind of fear when you go into the hearing office,’ and immediately John dropped down to the floor, took a handkerchief out of his pocket and started shining Vinnie Schiano’s shoes. He asked, ‘Is there anything else I can do for you, Mr. Schiano?’ It was a touching moment, as we went into the hearing.

Personal Notes

PB: A writer who attended a deportation hearing described you then as clearly conservative in terms of dress. You countered: 'But as time went on, I grew my hair longer—and bought my first pair of jeans.' You also talked about spending long hours at The Record Plant in NYC. It seems like working with the counter-culture transformed you in a number of ways.

LW: I didn’t know who John Lennon was. I probably had heard of The Beatles. It never took a place in my memory, so that when I came home that night, and told my wife that I had met with Jack Lemmon and Yoko Moto, it wasn’t a question of not remembering names: it was a question of having no idea who they were.

Last weekend, I appeared at The Fest for Beatles Fans in Chicago. I spoke there three times and every time after I spoke, dozens of people came up, shook my hand and thanked me for what I had done for John Lennon. And I learned from these wonderful people that it is really something to marvel about and to enjoy this beautiful music of The Beatles. I learned a lot about that kind of music and now I favour it as well.

And certainly living through those pressure-filled years with John and Yoko and watching them being followed by FBI agents — they would get into their car and drive someplace; the agents would be following them in their car and be behind them. They made it known that they were there. The situation was that they weren’t trying to hide it; they were trying to scare the hell out of them.

PB: What became crucial for you to convey when conceptualising the book? Did you feel you could communicate clearly to lay people?

LW: I probably was always very good at explaining divergent problems to my clients and I suppose that’s how I impressed John and Yoko and their very, impressive agent and his lawyer, when I was first taken to John’s apartment to see how I could help them, and apparently I gave them advice that nobody else that they had been consulting with ever even mentioned, and as a result, they saw openings, where a case like this, which was taught to be something that could never be won; they looked at it, like, well, it’s a very difficult case, but it’s not inconceivable that it could be won. That’s what made the difference.

I remember asking John, when he showed me his conviction — it said that he was being convicted of having cannabis resin without authorisation. I asked him about the difference between cannabis resin and narcotic drugs. Clearly we all understood that cannabis resin was not a narcotic drug, but we didn’t know if it was the same as marijuana. The statute said you could not be in possession of marijuana. I asked John, 'Is cannabis resin the same as marijuana?' and he said, 'No, of course not. It’s much better than marijuana.' (Laughs)

Below is an excerpt of the immigration statute (pg. 18, 'John Lennon vs. the USA', by Leon Wildes)

'People are excludable from the United States “who have been convicted of any law or regulation relating to the illicit possession of...narcotic drugs or marijuana.”

LW; So that gave us both the idea of having a witness testify that it is not marijuana, also trying to challenge whether the situation involved actually having possession. You recall that in the book, we describe the Scotland Yard officer who arrested John; he was out to arrest as many violators of drug laws as he could get, and as a result, he was asked why he was so intent on getting those musicians. He said, 'Because they are ruining the youth of the U.K., they’re ruining England’s youth.' He was out to get them and he harassed a lot of the other people that John knew, too.

John knew that he did not have any drugs in his apartment when he got to his place, but somehow, they found it. And after a while, as we were handling the case, Sergeant Pilcher, the guy who arrested him, came under charges that he had planted marijuana or some other drug on other people. It was pretty obvious that if he were going to get charged with this, that he might have done this in John’s case, too, because John didn’t have any drugs in his apartment.

The food that they ate; they had to follow a certain routine. Any drug, including marijuana, would not have been in their possession. As a result, we thought that it was likely that the government had arrested him after planting the drugs in his apartment. In other words, the policeman, who came to check the drugs with the dogs, came in with drugs and the dogs, and had the dogs find the drugs. That goes back to about 1968. There is a chapter in the book, describing what was going on at that time, as well.

Winning the Case.

PB: October 8, 1975. What was so significant about that day?

LW: That was a magnificent day and I remember it very clearly. I got a call on my telephone. I always answered my phone very carefully because my phones were being tapped by the FBI, and if it wasn’t the FBI, it was one of the other dozens of organizations that did that kind of work at the time.

A young man on the phone said to me, ‘Mr. Wildes, I shouldn’t be doing this but I’m a Lennon fan and I have the court decision in my hand here, which has just been signed by the three judges in the case. It may not be final; one of the judges might come by and change a few words or something like that, so I can’t release it completely but I’ll let you have a copy if you keep it privately until it is formally released'. I said, ‘Thank you very much. I’ll send somebody over for it.’

I called John and he answered the phone in a high-pitched, female-sounding voice because he knew his phones were being tapped, too, and we didn’t know how to react to it being tapped. Neither of us had done anything illegal. “

As a result, I said, ‘John, we’ve won the case.’ He said, ‘What do you mean, we’ve won the case? You said that it had been unlikely that we’d ever win the case.’ I said, ‘That that’s how I handle some of my clients, because I don’t want you to be disappointed if I don’t succeed, but we won it.”

He said, ’I’m just at home. Yoko is already in New York Hospital. She’s going to give birth tonight or tomorrow morning. I’m going over there now and I’ll call you from there and we’ll figure out what to do.'

I said, ‘John, I’ll try to get a copy of the decision’. When he called, Yoko said to me, ‘You and your wife, Ruth, should come over so you can read the decision together. We are so impressed that you actually won the case.’

They were under the impression that nobody had won such a case and they thought I’d really done an extraordinary job.

Yoko and I sat through my reading of the decision. It was a long decision. She understood every word. She was a very bright girl and I had had a lot of experience dealing with her during the case. John was not as anxious to get involved in the nitty gritty of the legal stuff.

Then my wife said to me, ‘She’s getting very uneasy. She may be giving birth very soon’. There were a lot of people going in and out of the room, just to take a look at John and Yoko, and I felt we should leave.

John said, ‘Leon, I’ll call you as soon as I have something to report’. Then we went home and I was exhausted. It was late. Then I got a call (about 1 am) and I said, ‘Who is this?’ He said, ‘This is John’. I said, ‘John who?’

This was an extraordinary circumstance. He said, ‘John Lennon, and I have a beautiful boy,’ and that’s one of his best songs that I love so much: ‘Beautiful Boy’.

I remember going out that day; we often exchanged gifts. I don’t remember the name of this very nice store, but as I walked in, I saw a passport case engraved with the seal of the United States. I said to the sales lady standing there, ‘I want to buy that for John.’

She said, ‘John?’ I said, ‘John Lennon. He deserves to have a passport case engraved with this seal because not only have we done something for him, but he has done an awful lot for the United States.’

The Importance of the John Lennon Case.

PB: Has your work in the field of immigration law had far-reaching effects?

LW: It’s already affecting future generations. Since that time, the government has been forced to look at those files and to look at all my articles describing what they mean, and to look at the decision in the Lennon case, and decisions in the other cases that they are required to decide on, in which there are people who should not be deported.

Imagine taking a paraplegic, forcing him into an airplane and sending him out of the United States because he is deportable: something that even the Immigration Services could never bring itself to do.

In so many of these cases, we have different philosophies of deportation which are being tested at this time, but certainly the case of the young people, those who were brought to the United States at a young age, and had nothing to do with coming here or making the arrangements. They don’t know any other country. They don’t know the language; removing them when they are accomplishing so much, rather than respecting them and their families; those people should not be removed.

In recent times, the government has been removing more people than they had done in years. Somebody had referred to former President Obama as 'deporter in chief' because during his years there were more deportations than in previous years, and that is not something that we should be continuing now. And I have a lot of respect for our new president, Donald Trump: there are a lot of things he does that are very good, but I think he has become too infused with the idea of reducing the number of people coming to the United States, especially in regards to relatives, because families building up in the United States have been one of our chief resources for America.

Since the Lennon case, that’s part of the immigration course that I taught, and since the handling of the case, for a very long time now, I gave an annual talk about the Lennon case. So I feel a lot has been accomplished, but not enough. I don’t think the government has accepted, as part of its routine, enough of the outcome of the Lennon case and I’m going to keep after them to see that more and more of this is developed.

Final Thoughts

PB: You wrote, “The boys’ contribution to the Lennon case often meant being without their daddy for five long years.” Besides raising a family, you held a demanding career and needed time to properly observe your religion. Looking back, do you have any regrets about taking on this ambitious case?

LW: No, I don’t have any regrets at all. In fact, as I think back on it, more and more glory came out of it and I am happy about the outcome that we received.

PB: Thank you.

In the interim, Yoko’s immigration legal needs are being handled by Leon’s son, Michael Wildes, who, interestingly, also represents Melania Trump and is her immigration lawyer. The firm and family are poised for yet a third generation as Michael’s children, Raquel and Joshua Wildes, are taking their father’s class at the Cardozo Law School in New York.

Lisa Torem would like to offer sincere thanks to Michael Wildes, Esq. Managing Partner WILDES & WEINBERG P.C.; Gabriella Elezovic, Executive Assistant to Michael Wildes; Christopher Torem, Esq. and, especially, Leon Wildes, WILDES & WEINBERG P.C., author of 'John Lennon vs. the USA'. The top photograph that accompanies this article was taken by Bob Gruen, and the other photographs are from the Wildes' Estate.

Picture Gallery:-