Miscellaneous

-

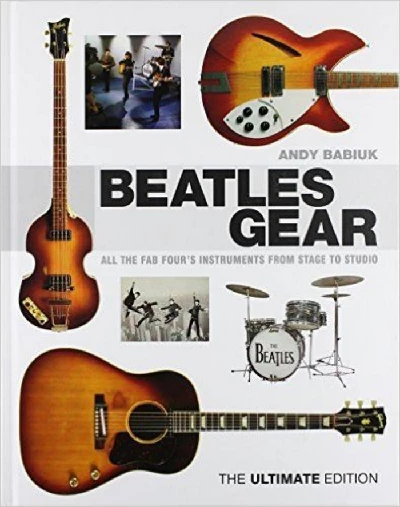

Beatles Gear: All the Fab Four's Instruments from Stage to Studio

published: 16 /

6 /

2016

Ben Howarth finds Andy Babiuk's book 'Beatles Gear: All the Fab Four's Instruments from Stage to Studio', which provides a history of the Beatles' equipment, to be original and unique

Article

A list of every musical instrument ever used by The Beatles would not necessarily be top of every fan's shopping list. There has always been a divide between music writing aimed at fans and the musician's press aimed squarely at aspiring performers. The assumption has been that non-musicians have no interest in the 'techy' side.

Enter, then, Andy Babiuk – a musician himself and also a dealer in rare guitars – to prove that assumption wrong with this jaw-droppingly well researched compendium of Beatles lore. This is an update to an earlier version of the book, and is billed 'The Ultimate Edition'. And ultimate it is. If you are thinking of buying this book, stop thinking about it and just buy it. But be warned, you'll need a new bookshelf as well. It's huge.

So, not only do you get photographs of all the instruments, you also get well-chosen pictures of the Beatles at work. This achieves not just what the writer himself was aiming at (an authoritative guide to the instruments and working methods of the greatest of all pop groups: tick), but also a genuinely unique take on the Beatles story. Despite having absorbed countless biographies and articles on the Beatles over the years, I found something unexpected on almost every page.

While in the middle of this book, I dug out the second volume of 'The Beatles: Live At The BBC', which was released a couple of years ago. As well as all the songs, there were one-on-one interviews with all four Beatles, recorded as they had adjusted to their fame. I was struck by the fact that, when asked what they liked to do when having time off from the band, none were able to give a convincing answer.

Of course, we know that John enjoyed comedy and had written a book, that Paul had begun attending the theatre and opera, that George was becoming interesting in Indian culture and that Ringo collected jewellery. But, actually, what they really did with their time off was more music – buying new instruments, writing new songs and building studios in their houses. In focussing perhaps too much on external factors (the feuds, the drugs, the business deals), no Beatles biographer has really nailed the obsession with their craft that made the Beatles so prolific and so adventurous. Until now.

It is clear that Babiuk himself is particularly fascinated in tracking down the gear the band used before they were famous, when they had the budget of a jobbing musician and couldn't rely on manufacturers begging them to use their equipment, even just once, so they could say the Beatles used it. So, a large amount of the book is devoted to the early years. He's spoken to various ancillary Quarrymen who all try and remember who lent which Beatles their first guitar.

By the halfway point of the book, we are in 1964. The Beatles, now clear that their unimaginable fame is not a flash in the pan, are enjoying the wealth that came with it and are in the middle of a significant upgrade in their equipment. 'A Hard Day's Night' starts with an unmistakable guitar chord and guitar riff. George Harrison's Rickenbacker became the definitive sound of the band's third album, the first on which they wrote all the songs and the one that, once and for all, set them apart from their 'Merseybeat' peers. From this point on, their competition would come from London and the US, not their local peers.

In fact, this new sound came to the band largely by chance. An enterprising distributor had picked up on the Beatles, even before they had arrived in the US, and saw them as a chance to expand his reach into the UK market, where the guitars were not yet available. It was his daughter who had noticed, having met a group of Liverpudlian Beatles fans, that Lennon – unusually – used a 1950s model Rickenbacker. Initially, he had hoped to persuade the band to use Rickenbacker amps, but Brian Epstein's 'gentleman's agreement' with Vox held throughout the band's touring days. Instead, it was George who embraced the 12-string Rickenbacker and its unique chiming sound. Countless bands were taking notes – but, by the time Roger McGuinn was making it the distinctive feature of The Byrds' new folk-rock sound, George Harrison had already moved on again, this time to a custom made Gretsch.

Babiuk's interest in the band's early years helps him draw insights into their later work. Even as the band focused increasingly on studio craft, their early versatility was the crucial distinguishing feature between them and other bands. Remarkably, for example, the showstopping rocker 'I'm Down' (composed to replace 'Twist and Shout' as the band's set-closer) was recorded at the same session as the tender, orchestral 'Yesterday'. The contrast between these two songs couldn't have been bigger – indeed, at the record breaking Shea Stadium, Lennon gave his organ such a furious pounding on this number that an emergency replacement was needed for the show in Toronto the next day (somewhat belying the myth that the Beatles weren't trying when they played these stadium shows to screaming crowds).

They may have been the biggest band in the world, but they were still bound by EMI's archaic studio rules for most of their career. The furious pace of the recording schedule meant that any new Lennon/McCartney number was typically learned by the band only 20 minutes before recording. This prompted the experiments and happy accidents that ensured each new Beatles record sounded different from the last one.

John Lennon's purchase of a Mellotron (retailing at what would now be the equivalent of £17,700) marks the point at which the book's focus moves away from guitars, drums and amps. The instrument was bought in the hope it would add a new dimension to the band's sound for 'Rubber Soul'. In fact, it did not actually appear on a Beatles record for another two years. Lennon eventually found a use for it on 'Strawberry Fields Forever', a song that went through multiple re-writes and edits as the arrangement moved further and further away from the band's established guitar-bass-drums set-up. (With the single at the top of Melody Maker's Pop 50, Mellotronics Ltd. took out an opportunistic advert alongside the chart).

By contrast, the new instrument that did add sparkle to the sound of 'Rubber Soul' was George's sitar – bought on the cheap and on something of a whim. Harrison would later become a devotee of the instrument and went to India to play with Ravi Shankar, but would admit that he didn't know how to play it when it appeared on 'Norwegian Wood'.

As we move on through the book, studio trickery takes increasing precedence. For example, the 'harpsichord' solo on 'In My Life' is, in fact, a piano speeded up to double time. George Martin freely admitted that he wasn't able to play the solo at the desired speed, so he simply sped the tape up. You would think, then, that Babiuk's focus on the 'gear' would become less relevant – but, in fact, it was often simple changes that kept the sound of each new record fresh. Take 'Day Tripper' for example, where a distinctive trebly guitar sound was the result of both Harrison and Lennon switching their pick-ups to the opposite side of their guitars.

An upgrade from Paul to his Hofner violin bass to a Rickenbacker (them again!), on the not unreasonable basis that it stayed in tune for longer, was the trigger to the bass and drums being pushed up higher in the mix. Paul was eager to keep pace with Motown, where bass was increasingly coming to the fore in the arrangements. Soon, the basslines were being meticulously crafted and added to the track as an overdub, taking the Beatles ever further from their traditional sound.

I was amazed to discover that the Beatles were the first band ever to record overdubs using headphones. Before then, overdubs were recorded with the original track playing on a loudspeaker, inevitably bleeding onto the tracks. Even more amazing is that this change didn't happen until 1966!

Alas, as the decade wore on, the Beatles became increasingly absent from public attention and increasingly fractured internally. As a result, there weren't as many photographers inside their studios taking promotional shots of the Beatles using certain instruments, and as a result, the well of material Babiuk has to draw on dries up from 'The White Album' onwards.

Still, if the photos are slightly less comprehensive, there is still plenty to say, and Babiuk remains insightful over what made the band tick – particularly for the rooftop concert that represented their final public appearance, and in particular, on the Fender Rhodes keyboard that Billy Preston added in his temporary role as the 'fifth Beatle'. A case is made that the increasing disinterest in their craft is the difference between the sub-standard 'Get Back/Let It Be' material (albeit still with a handful of genuinely great songs). There is also a touching aside to be found when Ringo, having tentatively begun writing songs, is presented a guitar by Lennon that he felt was the easiest to write songs with (mainly because it was slightly smaller than average).

On his last album, Paul McCartney attempted to reclaim his memories of the Beatles legacy from the many biographers who have focussed more on the soap opera. Not unreasonably, McCartney has often questioned whether the many negative anecdotes can really be true, given that this was the most successful band of all time. It does 'Beatles Gear' no disservice to say that I suspect this is a Beatles book that McCartney would genuinely enjoy. It is not a critical assessment of their work - quite frankly, a project of this kind is only justified if you take it as a given that the band's work is worthy of the time and attention). But, it is insightful, original and endlessly fascinating. In short, a monumental piece of work to rank alongside the very best in Beatle biographies.