published: 16 /

6 /

2016

John Clarkson speaks to Associates' keyboardist and guitarist Alan Rankine about the re-release in double CD editions of their first three albums, 'The Affectionate Punch', 'Fourth Drawer Down' and 'Sulk', and their late vocalist Billy MacKenzie

Article

When Billy MacKenzie took his own life in the shed of his family home in Auchterhouse, just North of Dundee, in January 1997, Scotland lost one of its most mercurial and flamboyant talents. The 39-year old singer, who overdosed on a combination of paracetamol and prescription drugs, had recently lost his mother to cancer and was suffering from clinical depression.

Billy MacKenzie also had a latter-day solo career and worked with artists as diverse as Shirley Bassey, Paul Haig from Josef K and the British Electric Foundation, but is best known for his band the Associates, which he formed in 1976 with keyboardist/guitarist Alan Rankine, who was living in Linlithgow near Edinburgh at the time.

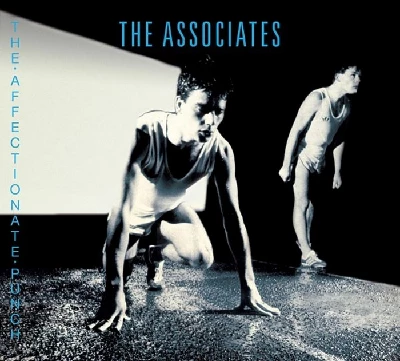

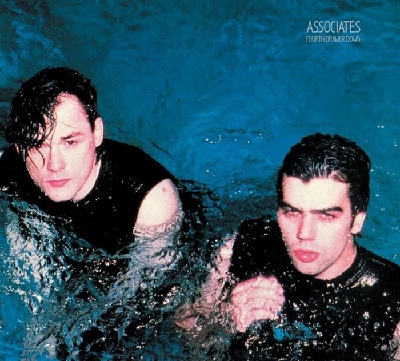

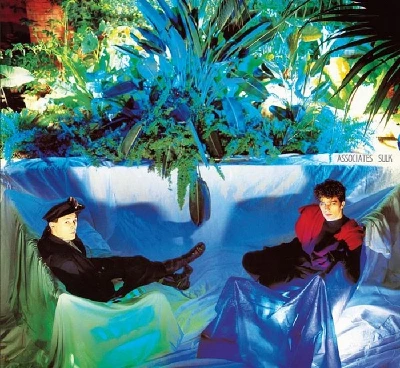

The duo recorded three extraordinary albums together, ‘The Affectionate Punch’ (Fiction, 1980), singles compilation ‘Fourth Drawer Down’ (Situation 2, 1981) and ‘Sulk’ (Beggar’s Banquet, 1982), which fused McKenzie’s near operatic vocals in a hybrid of disco, torch song, electronica and art rock. They also had Top 20 chart hits with ‘Party Fears Two’ (1981) and ‘Club Country’ (1982), but split up in early 1982 at the height of their fame when MacKenzie, who would go on to record another two albums using the Associates moniker, suddenly refused to tour.

‘The Affectionate Punch’, ‘Fourth Drawer Down’ and ‘Sulk’ have all just been reissued by BMG, along with a new compilation, ‘The Very Best of the Associates’, in double CD editions. While these albums have all been re-released before, these reissues carry more credibility than the previous re-releases, having been curated and produced by Michael Dempsey, who was the bass player on ‘Fourth Drawer Down’ and ‘Sulk’. They also feature various unreleased tracks, demos, live recordings and rarities including several songs MacKenzie and Rankine recorded during a brief reunion in 1993, and carry extensive liner notes from music journalist and long-term Associates fan Martin Aston and MacKenzie’s biographer Tom Doyle.

In a rare interview , Alan Rankine spoke Pennyblackmusic about the reissues and his friendship with Billy MacKenzie.

PB: You have said that these new reissues are “far and away the best packages of our music.” There have been various other Associates reissues over the years. Why do you think that this latest set of reissues have the edge?

AR: Warner Brothers did various reissues and retrospectives when Bill was still alive and V2 Music did the same kind of thing about ten years ago, but they didn’t spend any time or put any attention into them whereas BMG have spent a lot of time on these and it shows.

When Michael Dempsey and I first became involved in this project, our own personal remit to each other was that this was going to be the Associates as in MacKenzie and Rankine, and we weren’t really interested in anything beyond that. That is not to decry anything that came after that, but the Associates latterly and for their last two albums (‘Perhaps’, 1985 and ‘Wild and Lonely’, 1990) were a very different animal. This set of reissues is not so much a tribute to Bill, but more a celebration of what Bill and I did together between the years of 1976 and the beginning of 1983 when I left.

What we have compiles together pretty much everything that Bill and I worked upon together and which is worth hearing. The three albums have also all been remastered and they all sound so much better.

PB: You and Billy broke up because of Billy’s refusal to tour after ‘Sulk‘ became a success. He, however, before then had no problems playing live and the year before toured Scotland successfully. Do you think that his real issue was with fame rather than because he suffered from stage fright?

AR: Yes. Once success began to take a hold, Bill realised that he didn’t really like the treadmill of it. He didn’t really like the idea of all the touring and other promotion that he could see that was looming in front of him. I could see it too and it was what I had been working towards. It is no detriment to Bill though that he decided that he didn’t want to do that. If you had put an imaginary, hypothetical itinerary in front of Bill and said, “Right, this is what you are doing for the next sixty days,” he would have just run a mile (Laughs).

When we toured in Scotland in June, July and August of 1980, there was nothing in the books more than ten days ahead. When we got down to London at the start of September that year, we did an ICA gig and then a month of Sundays at the Marquee, but Bill was okay with that because there were seven days between each gig. It was more rock and roll than we had been doing, but the idea of putting together an itinerary and saying that you must be here then or someone will pick you up at this time was a total anathema to him.

When “The True Associates” as I call them - this line-up of Bill, myself, Michael Dempsey and John Murphy, the drummer who has just passed away recently - were touring Scotland, Bill had no fear at all as it really felt very, very fresh and exciting. As soon as you started putting things into boxes, though, that was when things came apart. For instance, Bill would have no stage fright whatsoever in his later years. He would fly into New York, just to do a simple playback instrumentation with him singing live vocals and six or seven songs, and then fly out the next day, and he would have played to 5, 000 or 6, 000 people in a gay club that night, but because it was a one-off gig that held no fear for him.

He just didn’t like having any kind of constraint on him. If Bill saw a roadie with a whole lot of keys on his belt, or another one with a bum crack like a plumber, that was enough to give him – I am sure that you are familiar with the expression- the “dry boak” (Laughs). He just didn’t like that that rock and roll side of the music business. It is no detriment to roadies either. They have a job to do, but he was like (adopts a Dundonian accent), “I cannae look at this. I cannae look at that anymore. That fucking bastard has got his fucking arse on show. How can he fucking do that?” There is a story about Bryan Ferry getting out of a helicopter to go and do a festival in a muddy field and he had his Gucci shoes on and he got mud on them, and he said, “No, we are not doing this (Laughs).” If you think about it, it was the same kind of thing.

PB: When did you and Billy first meet?

AR: I saw him performing in Tiffany’s Ballroom in Edinburgh one night with a cod-funk outfit whose name I can’t remember and while I wasn’t impressed with them I was with him. So, I got a pal of mine to get in touch with a pal of Bill’s and two weeks later Bill was down in Edinburgh stepping out of a cab. At that time I had hair down to my frigging arse and a stinking Afghan coat, and I am sure that Bill thought to himself, “Christ almighty, what have I got myself into here?”, but within three days I had cut off my hair and he was sleeping on the couch in my and my girlfriend’s lounge in Linlithgow.

It was an instant connection. Bill was staying in some kind of band flat, and he drew me aside during rehearsals on the third day and said, “Man, you have got get me out of here. I cannae stand the testosterone there,” and I could see the pleading in his eyes, and I said, “Okay, man. You can come and live with me and my girlfriend,” and immediately he relaxed and we just started writing songs.

PB: How did the song writing between the two of you work? Did Billy provide lyrics and you the music?

AR: In the very early days, back in 1976, believe it or not, Bill was very, very organised about his lyrics. He had them in poly pockets in a binder. His lyrics were a little naïve at first. They involved a lot of spoonerisms and playing with words, and that was the only time that I said to Bill, “This one is okay, but you need to develop this one and that one and take them somewhere else.” He got what I meant straightaway and after that I left Bill to his own devices with the lyrics. It was always important not to constrict him. He had to expand in his own way and he just grew and after that.

I think I only contributed to the lyrics on one occasion and it was with the song ‘Skipping’ on ‘The Affectionate Punch’. I came up with the line “Doors lead to other doors/Roads lead to other roads/It is simple/They just happen”, and Bill liked the defiant innocence of it and so we went with that and that became ‘Skipping’. But other than that, all the lyrics were his.

PB: What about the music? Was that all written by you?

AR: No. It is very wrong to think of Bill as just a singer. He didn’t play an instrument, but he was a fantastic musician. He was a fantastic interpreter. Sometimes he would have half a lyric, probably not the whole lyric, but that would spark something in me and sometimes I would have a riff or a melody and that would start something in Bill. It sounds clichéd, but it got to the stage we were almost telepathic.

PB: Did that telepathy continue when you got back together in 1993?

AR: We hadn’t seen each other in eleven years, apart from one brief occasion in 1990 when Bill happened to be staying in the same hotel that I was when he was doing a radio promotion tour. I think he was promoting ‘Wild and Lonely’, and we didn’t really talk very much then.

When we did get back together in 1993 though, it was like I hadn’t met Bill in two weeks and vice versa. That was how it felt. It didn’t feel like eleven years. We started by writing ‘Stephen, You’re Really Something’ and we did that in just fifteen minutes. We were immediately back to where we were, but wanted to write something fun and not too deep that would break the ice and ‘Stephen, You’re Really Something’ did just that . (‘Stephen, You’re Really Something’ was written in response to the Smiths’ ‘William, It Was Really Nothing’, which is allegedly about Morrissey’s own brief friendship with Mackenzie –Ed).

PB: When you reformed, how long were you back together for?

AR: I remember a review of Bill’s solo album ‘Outernational’ by Martin Aston came out in the autumn of 1992 , and a few days later Bill phoned me. There is quite a story to that and I never thought about it at the time, but how did Bill get my number? My father, who is still alive, didn’t tell me this story until a few years ago. He said that Bill’s father had phoned him and had asked for my number and said, “Will you please not tell anyone until I am dead? (Laughs). So the two Jims, Jim MacKenzie and Jim Rankine had this pact, and I never knew about that until five or so years ago when Bill’s dad died that that conversation had taken place.

Bill got in touch with me because Martin Aston’s review ended with the line of “Surely it is time for him to phone Rankine” or something like that. We had a few things to clear up. Then we got together in February of 1993 and we were recording together until May 1993. After that, Bill wanted to go off and do other projects which was fair enough.

PB: Why did you split up again?

AR: It was the same thing. We had record companies interested, but they were all saying the same thing. They were saying prove it. In other words play live. Let’s see it. Let’s experience it, and that was just like a red rag to a bull to Bill. He just wouldn’t do that. It just slowly fell apart. There was no big pow-wow or anything. It just came to nothing.

PB: How much contact did you have with him after that reunion?

AR: The last time I saw Bill alive was in November of 1993 and I had no contact with him whatsoever until someone phoned me up in January 1997 to tell me that he had killed himself.

I didn’t think Bill would do that. Bill may have been as camp as anything but he had an inner strength that was just phenomenal and I really didn’t have that on my horizon that he would do that. It was a terrible shock. Things can take a worse for anybody though, and that is what happened here.

PB: Crime writer Ian Rankin’s latest Rebus novel ‘Even Dogs in the Wild’ takes its name from the Associates single of the same name. Was that something that you knew about before it was published last November?

AR: I knew that it was going to be called ‘Even Dogs in the Wild’. I have read every Ian Rankin novel and like his style of writing and like the Rebus thing. I had always imagined Rebus as Ken Stott in my head even before he played him on TV. I also liked the fact because they are all set in Edinburgh that I knew the streets and the areas that Ian Rankin was talking about. Ian Rankin does a lot to plug Scottish music in his novels, and all the time I was thinking, “Deacon Blue got a mention, so and so got a mention, but where the fuck are we? (Laughs)” And then all of a sudden he comes out and names the book after that song, and works a tape recording of it into the plot line.

PB: Do you have any other plans for the Associates once these reissues are out?

AR: I would like to get the reissues out of the way, but then I would like to do a one-off concert as a celebration of the True Associates. We would have a guest singer who wouldn’t be a sound-a-like for Bill, but who would have his own take on things. I would like to do that for those who didn’t see us in 1980 or 1981. I also think people would like to see something if they can’t have the real thing and this would not be some overblown nine-piece band. This would just be myself, Dempsey, the singer, drummer and an occasional keyboard part. We will see if that happens.

PB: Thank you.

Photos by Sheila Rock

Picture Gallery:-