published: 22 /

7 /

2015

Dennis Dunaway, the bassist and co-songwriter/co-founder of Alice Cooper, has just published his memoir. In this two -part interview he discusses the history of the band, the making of their hits and studio life with Lisa Torem

Article

Formed in the 1960s, the Alice Cooper group has influenced KISS, the New York Dolls and Marilyn Manson and so many more outstanding bands by way of singable, shock-rock anthems, over-the-top stage shows, glitzy makeup and dazzling pyrotechnics. The band was originally formed in Phoenix by Vince Furnier (the future Alice) and bassist Dennis Dunaway, whose imaginative song crafting, kinesthetic technique and arranging ingenuity became the backbone for songs such as ‘I’m 18’, ‘School’s Out’ and ‘Elected’. Boasting four platinum albums and a chart soaring sweep over the U.S. and U.K. with their 1973 number one album ‘Billion Dollar Babies,’ the band appeared unstoppable.

But in Dunaway’s new memoir, ‘Snakes!Guillotines!ElectricChairs! My Adventures in The Alice Cooper Group’, co-written with Chris Hodenfield, Dennis clues us in on the more complete story of the band’s lean early days and how they dealt with seemingly insurmountable odds as well as studio dynamics.

Inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2011, Dunaway, who is currently promoting the memoir in America, has come full circle, surviving serious illness and coming to terms with the then unexpected demise of his childhood band, while still celebrating life with his daughters and wife, Cindy Dunaway, whose visionary fashion instincts and emotional versatility made her as much a part of the original band as Michael Bruce (rhythm guitar and keyboards), Neal Smith (drums), Glen Buxton (lead guitar), Alice Cooper and Dennis.

With tremendous insight and candour, Dennis spoke with Pennyblackmusic for an exclusive first-time interview. He is currently on the road with Blue Coupe, in which he performs and writes with the dynamic Bouchard Brothers (Blue Oyster Cult).

PB: In your memoir, you provide us with a unique bird’s eye view of the 1970s music industry, and more specifically, insights into early Alice Cooper band dynamics. But let’s start with one of your interesting quotes on early influences. You stated: “Michael, Glen and I grew more experimental with our cover tunes. One of the great records of that year, 1966, was Paul Butterfield’s ‘East West’.” Did the discovery of that song lead to a turning point for you and the band musically?

DD: It was and not just for our group. That song, in particular, ‘East West’, a long drawn out raga thing that went around the world in musical styles, influenced a lot of bands—that’s why they’re in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame now.

I remembered we played in Albuquerque and we kind of ran out of songs because we had to do four sets, so we played ‘East West’ for about half an hour and all of a sudden it brought this revelation that we could just jam in front of people and they’ll enjoy it. So, that gave us the courage to start experimenting and exploring musical boundaries and writing our own material.

PB: You also stated that you and Vince (Furnier AKA Alice Cooper) began to imagine staging and lighting in conceptual terms and that there were about 3,000 bands in LA. that were also seeking work. You had such a strong vision for success despite the odds that most bands would simply not make it.

DD: The competition was very heavy in LA. Even though we did eventually leave LA with our tails between our legs, on the other hand we had gigs. We played more than most of the bands that were there. A lot of them just went there and couldn’t get an audition. It wasn’t just tough between all of the bands’ competitions, but you would have—Jimi Hendrix would just walk in off the street with his guitar and walk up on stage and plug in with a band and jam for the rest of the night, so it was very hard to get paid. But we did. We were the house band at the Cheetah Ballroom and we played The Experience.

The guy that owned The Experience, Marshall Brevitz, was an early supporter of the band. He had this psychedelic shop on Hollywood and Vine called the Psychedelic Supermarket. During after hours, he closed the shop and we set up our equipment right in the middle of all those psychedelic posters hanging on the walls, and we’d have a rehearsal place and then he hired us fairly often during the short-lived era of the club. It only lasted a year because Marshall loved food. He liked to give people a good deal on food and he was everybody’s friend, so if you ordered a sandwich you got a feast and then you could just run a tab because he was that nice. Everybody was running tabs and not all of them were paying them, so the club didn’t last that long unfortunately.

It was a great club. The front of it had a big painting of Jimi Hendrix’s head and you kind of walked through his mouth—the entrance—and Jimi would show up pretty often.

PB: But getting back to the early vision, you set your sights extremely high for the time. It was more than ‘We’re a rock band.’ You were determined to have artistic control of your stage persona.

DD: The lighting has to be credited to our high school buddy, Charlie Carnell, who was with the group all the way through the original group’s career. He went to the Army Navy Store because back then you could get army supplies cheap at the Navy Store. He would buy these munitions canisters and cut a hole in the end and put tin foil and a really bright light inside. Then he would cut out a piece of tin with a couple of slits in it that would spin and then when the slit would get in front of the light it would let the light through, so it was like a very organic version of a strobe as compared to the erratic feel of an electronic strobe. He was very artistic, and so art was really the basis of pretty much everything we did. He made the lights go with each part of each song, so we would have footlights that were coloured gels. Then he would unlatch them and drop down the coloured gel, so it would just be stark, white photo bulbs and giant shadows would be jumping all over the wall behind us. We could have stood still and it would have looked like we were jumping around, but we were jumping around as well. So, all of this was an artistic statement but it was all just for the fun of it and it was also to get attention. We wanted people to walk out whether they liked it or not. We wanted them to be talking about it, and that’s what we managed to do.

PB: The 2013 documentary, ‘Supermensch: The Legend of Shep Gordon’ shed light on a few of the early publicity stunts that co-managers Shep Gordon and Joe Greenberg put into place, which were quite inventive and really worked.

DD: Alice and I started doing that all the way back in high school for The Earwigs. We both were in journalism class and both worked on the newspaper, ‘The Tipsheet’. We ran long distance and we managed to weasel the long distance team into the paper a lot more than most schools would because back then long distance running cross country was just not important. It was way down the ladder of cool, but we managed to glorify it and rightfully so.

We were a really good team. We were undefeated in our division, with nine wins and no losses. So we already had that sensationalizing kind of attitude, and then when we hooked up with our managers we knew that if you wanted to get publicity you needed to try to get into the mainstream news rather than just the rock and roll; where the bands were playing.

And we learned that lesson from the Rolling Stones. They had the big press about things that they did that didn’t happen onstage. And these days when you look at all the things that the Paparazzi cover, you realize that most young artists these days realize that—who goes out with whom, the DUI driving, that’s how you get in the mainstream news. Whether it’s good or bad, your name is out there.

PB: Your regular producer Bob Ezrin worked the band very hard. His goal at the time was to give Alice Cooper a more commercial sound, yet those songs were your babies. Was it difficult to relinquish control?

DD: There are two kinds of producers. There’s a producer who is there to get whatever the band is doing, to get the best of what they want to do onto a record, and that’s what Bob did in the beginning, and that’s what we sought him out for. We knew we needed hits or we were going to go under, and so we were wide open to all of it. We just didn’t know how to do it and when he came in we were sponges. We soaked it all up.

Everything worked very well that way, but then with success all of a sudden he sort of started leaning toward the other kind of producer which is the Phil Spector type, where the musicians are replaceable and expendable. With one producer people end up saying, “the band, the band it’s great”—the other kind of producer is going for, “Oh, the production is great.” So he sort of shifted towards that, and our biggest album was ‘Billion Dollar Babies’ and that was slicker, more in the Bob Ezrin vein of what he shifted to.

All the way up until ‘School’s Out’, it was the band writing and doing our vision. Then on ‘Billion Dollar Babies’ it shifted, and all of a sudden we had people telling us we’re not going to do that song that you just wrote, We’re going to do that song that Alice and I wrote. So there was friction over that even though to this day I enjoy working with Bob. I love what he does with the bass and he’s a really nice guy. He’s fun to be around.

PB: Speaking of the bass, you had some revelations in terms of arranging. How has your playing developed over the years?

DD: First of all, I began with blues patterns. With the Alice Cooper Group, even on our first album ‘Pretties For You’, all of those things began as blues rooted patterns and we would just stretch them and take them somewhere beyond.

’I’m 18’ is a very bluesy kind of a song. When I got my very first bass, an Airline, from Montgomery Ward, I would go over to Glen Buxton’s house and we would sit in his living room, next to his parents’ stereo console and drop the needle on the record and pick out the notes and keep playing it over and over until we figured out the patterns, mostly of Rolling Stones’ songs.

PB: You mentioned Bill Wyman as one of your influences.

DD: Bill Wyman was playing his own unique version of American blues, but history is funny that way. American blues was not popular in America until the British Invasion brought it to our attention. Anyway, I’m learning American blues patterns from a Brit and blues artists all were very happy about that. They tipped their hat. They were baffled, but at least all of a sudden people were finding out who B.B. King was.

The Yardbirds were the biggest influence on us. Everybody talks about the guitar players. They had Eric Clapton, Jeff Beck and Jimmy Page in the same band, and of course that will overshadow anybody including Chris Dreja, who was the guitar player that was with them throughout all of that. Nobody ever talks about him, but he was great, too.

But in my opinion, Paul Samwell-Smith, the Yardbirds bassist was equally as pioneering. When we started learning the Yardbirds songs very early on, I took this lesson from them in bass that it does not have to just follow the root notes and hold down the pocket.

If you asked me who my favourite bassist is or my favourite bass parts, its mind boggling because I can hardly find a bassist that I don’t like. But more than me just trying to imitate what Paul Samwell-Smith did, basically it was just this concept that bass could really push the boundaries and that freed me to think on those terms. I could do anything on any part of the song. Now I did have to hold down the pocket, but my friend from Iceland, a bassist in this band, Dimma, he said that what he thought was unique about my style is that I hold down the pocket . Then every once in a while I’ll jump up and grab people’s attention and pull them back down there with me, and I guess that’s true. I wasn’t consciously trying to do that but most bassists—there are some great bass players like John McVie from Fleetwood Mac. He plays these great bass parts that really support everything. The bass is the foundation of the tower of music. If he stopped playing, all of a sudden you’d realize what he was doing.

On ‘Pretties For You’, I kind of let the pockets of the songs go out the window. I really was just going for this avant garde, abstract expression that nobody had every done before and it was very explorational, but then after that we realized that wasn’t putting any food on the table we decided we would have to do things that were more relatable Therefore I decided, “Okay, I’m going to hold down the pocket but I’m not going to give up this other expression that the bass can do.” So, it was all a happy medium with a lot of experimentation, which I also credit Bob Ezrin for being very patient with. Neal and I both were both very, very experimental. We each had to try a hundred parts before we would settle on anything—each bridge had us trying everything we could think of before we decided what was best for that part.

PB: Let’s talk about your current band. Blue Coupe and the song, ‘Waiting for the Ship to Come In.’ The lyric, “Just waiting for the cash to flow…” It’s told from the perspective of a guy fuelled by fantasy. And I see this thread which, I believe, started in Alice Cooper, this thread of youthfulness. The underlying message? You can dream anything. No one can stop you. ‘School’s Out’ is still so popular. It’s a great anthem and a great high, and, of course, it celebrates youth so genuinely. So you can be eighteen or you can be an older guy pinning his hopes on a Bermuda holiday even though he’s flat broke. There’s that same optimism.

DD: We imagined all that way back in high school with The Earwigs when people were laughing at our act. We imagined us as being one of the valiant bands that was out there during the British Invasion. And there are artists that write from a realistic point of view. They write about real things that happened in their lives and then there are songs that are fantasy. Most of our songs were fantasy. We were creating this world in our mind and it was all based around this Alice Cooper character, and I still write a lot of things that are fantasy.

‘Waiting for My Ship to Come In’ is half and half and a lot of it is like that as well. And that was partially inspired by Neal and Cindy’s cousin from Ohio, who we called the Baron Von Dot. He worked for the Alice Cooper group for a while. He was always talking about what he was going to do when he gets rich, but he’d never get out of his chair to do anything to get the money. So, that was the initial inspiration. He’s just waiting for his ship to come in. He’s not doing anything to make it come in any faster.

PB: When you are a teenager, you can feel like the world’s against you. You’re dying for autonomy but you’re still bound by societal and parental rules. ‘I’m 18’ really encapsulates all that want and desire and pent up rage.

DD: You’re talking about five guys that went to school during the same period in the 1960s in the same state and had all of the same feelings about school. Even though there’s a universal theme to that message, we easily could revert to being teenagers together. And, also, let’s face it, there’s a factor of immaturity in musicians to begin with. (Laughs). I always say, “If rock music don’t kill you, it will make you young.”

We easily could click into that mentality. And there was a conscious idea that we knew that the target audience, the record buying public were kids that still lived at home with their parents, so we said that’s who we want to write a song for because they can afford to buy records

The song actually started out as a long, sprawling warm-up jam. This thing would go on for ten minutes, and Alice would play harmonica and throw out some lyrics and Michael would throw out some lyrics and the rest of us, if we thought of anything, it would almost be like, “Okay, Dennis, take a verse. Neil, take a verse.” We would just play with it.

It started to come together even though it was a longer version that started out with a very bluesy organ part. When we played this at Max’s Kansas City - Bob Ezrin was in the audience, we didn’t know he was there - -that night, we were very upset because we got to NYC and we hadn’t had a good track record there. We’d gotten the cold shoulder every time we came to that city; it’s a jaded audience. But we do our whole show for people that have their arms folded. We had just came from Detroit, and that’s where everybody had their fists in the air. It was kind of frustrating. Now we get to Max’s Kansas City and there’s like five people there. Andy Warhol had already taken all of his paintings off the wall, so you could even see the shadows where the paintings were hanging.

We got there and there was no dressing room because it was filled with cases of empty beer bottles, so we had to tune up on the stairwell and everyone’s like, “Let’s not even play. Did anybody advertise this? What’s going on here?”

I used to always be the “one-for-the-gipper guy” and I said, “The smaller the crowd, the bigger the rumours.” And Glen Buxton said, “What if we don’t play and start a rumour that we did?” But more people did arrive. It wasn’t packed like Bob Ezrin always remembers it, with people with Alice Cooper make-up and stuff. The make-up was new then and I don’t remember it that way.

But we were very upset and when we played we took all that frustration into the show, and it had this feeling of aggression. Ezrin actually thought ‘I’m 18’ was ‘I’m Edgy’.

So when we got back to studio, we found we were going to have to work this kid. We always called him the ‘Boy Wonder’, but he was older than he looked. We thought we were going for Jack Richardson, this older statesman in the business, and we end up with this kid. He shows up and he’s saying, “I think you guys have something that’s going to be really big, but you’re not getting it into the grooves on the record.” We know that. That’s why we were trying to get Jack Richardson to produce us.”

So at that point we clued him in that the song was ‘I’m 18’, and we’re going to make like a Reader’s Digest AM radio version of it. Back then, FM radio would play the one version and AM needed the concise three-minute songs, unless you were the Beatles. We whittled it down. The very first afternoon we had ‘I’m 18’ finished, and he taught us how to take everything apart, dissect every part and put it back together. So all of a sudden the bass drum wasn’t playing where the bass wasn’t. That was locked in and everything that was locked in was proper.

Now we were already playing the song with that feel, but we weren’t getting it down to where every tiny detail was on target and those are the kind of things that sound fine to most bands when they’re rehearsing, and then when you get in the studio that has that magnifying glass and every tiny little flaw stands out, all of a sudden you go into shock because you hear all of these things that need to be fixed, so we fixed them before we went in the studio and it was the first time we had had a chance to do that.

Our first two records would have been better had we had that opportunity but we also, between ‘Pretties for You’ and ‘Easy Action,’ had become better songwriters. It wasn’t that we weren’t good musicians because we were pretty darn good way back when we were a covers band. It’s just when we started doing this experimental stuff and started exploring that we were searching, so it didn’t have that impact. We hadn’t found it yet.

Michael had done a lot of wood shedding. In other words, sitting in his room with his guitar, just practicing, practicing, practicing. He started coming up with these great songs, and when Bob showed up he had a lot more to work with than we had when we went into the studio on our first two albums. So that helped, too. Alice always said that Bob taught us how to play, but I have a different opinion of that. I think we could play. We just didn’t know how to get songs into an AM format.

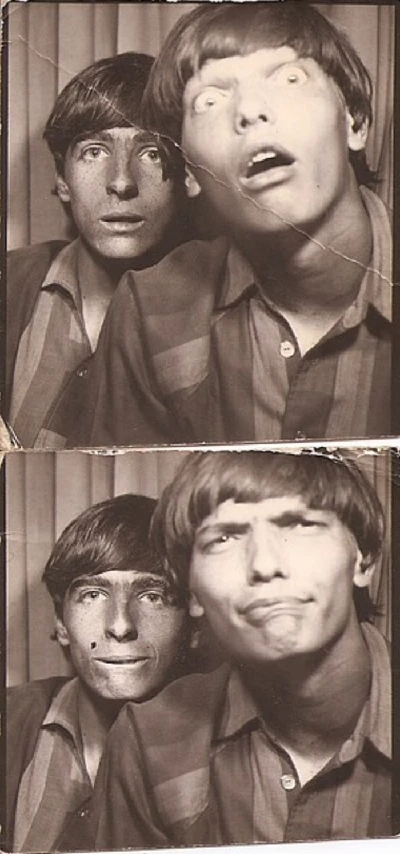

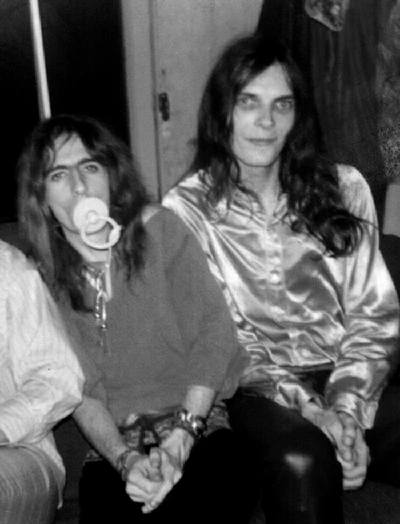

The top photo of the Alice Cooper band was taken in 1972 by Cindy Smith Dunaway. The second photograph of Alice Cooper shows Alice Cooper and Dennis Dunaway as sixteen year olds in 1965, while the third photograph, again of Alice Cooper and Dennis Dunaway, was taken in 1969 by Monica Lauer. The final photograph of Dennis Dunaway and Cindy Smith Dunaway was taken at the Ambassador Hotel Hollywood again by Monica Lauer.

Band Links:-

http://www.dennisdunaway.com/

https://www.facebook.com/dunawaysrock

http://www.sickthingsuk.co.uk/

Picture Gallery:-