published: 3 /

4 /

2014

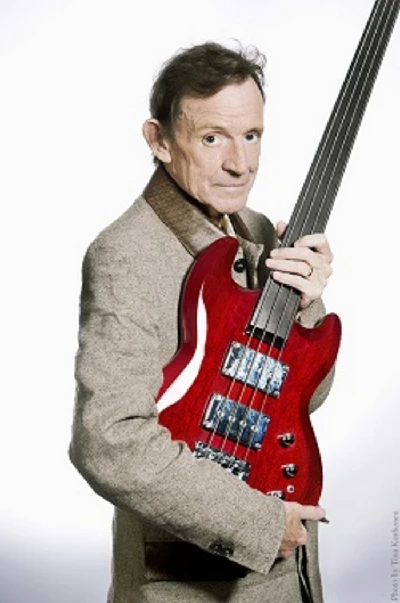

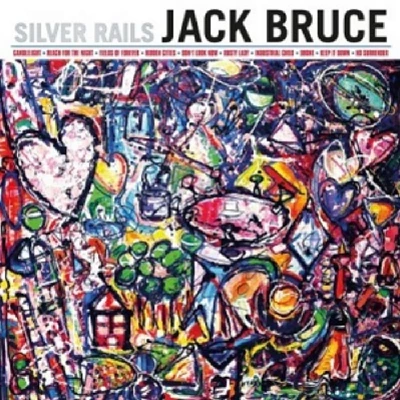

Lisa Torem speaks to former Cream bassist and music legend Jack Bruce about his new solo album, 'Silver Rails'

Article

Scottish multi-instrumentalist Jack Bruce began playing upright bass as a teen. His early professional years including playing with the Graham Bond Quartet, with drummer Ginger Baker and guitarist John McLaughlin. They played bebop, blues and rhythm and blues. In the mid-1960s, he joined John Mayall and the Bluesbreakers, featuring Eric Clapton. In 1966, after a short stint with Manfred Mann, he formed power trio Cream with Clapton and Baker. Bruce became lead vocalist, bass player and co-writer, with poet Pete Brown, of songs such as ‘Sunshine of Your Love’, ‘White Room’ and ‘I Feel Free’. Despite only being together for two years, Cream changed the course of rock music by infusing many of their arrangements with irregular rhythms, unforgettable bass lines and imaginative themes.

After Cream disbanded, Bruce forged a lengthy solo career. His debut ‘Songs for a Tailor’ was released in 1969. He then joined Lifetime, a jazz-fusion band featuring drummer Tony Williams, organist Larry Young and long-time colleague McLaughlin. They broke up in 1971.

Bruce formed West, Bruce and Laing, another power trio with guitarist Leslie West (Mountain) and drummer Corky Laing, which ended in 1974. During this time, he also released his fourth solo album ‘Out of the Storm’ and contributed to Frank Zappa’s ‘Apostrophe’.

In the 1980s Bruce married Margrit Seyffer, who became his manager and the co-writer of ‘Candlelight’ on his new album, ‘Silver Rails’. He also began working with British guitarist Robin Trower. They collaborated on BLT and Truce.

In 1983 he began a musical partnership with Kip Hanrahan, who is known for producing Latin and World Music records. At the end of this decade he toured with Baker, and in the beginning of the 1990s Bruce played at the Montreux Jazz Festival with Rory Gallagher and with guitarist Gary Moore in Cologne, Germany. That concert resulted in the double album, ‘Cities of the Heart’. Bruce also toured with Ringo Starr.

In the early part of 2000 Bruce worked with Bernie Worrell, Vernon Reid (Living Colour) and with Hanrahan’s Latin rhythm section. This line-up recorded ‘Shadows in the Air’ and another Hanrahan album, the critically acclaimed ‘More Jack Than God’ in 2003.

2005 highlights include the Cream reunion, held at London’s Royal Albert Hall and New York’s Madison Square Garden. It was during this decade that Bruce underwent a liver transplant, so he spent time recovering. He recorded the groundbreaking ‘Seven Moons’ with Trower and began a successful line-up of club dates at London’s famed venue, Ronnie Scott’s Club.

In 2011, Bruce received the International Bassist Award at NAMMS. Scottish BBC released the documentary, ‘The Man behind the Bass’, in February of 2012. Bruce’s contributions to rock continue to reverberate. His unique gifts for constructing melodic bass lines coupled with his consistent knack for creating outside-the-lines compositions render him a rarity. With a new batch of original songs and an enviable guest list on new release ‘Silver Rails’ (Esoteric), Bruce had a lot to say in interview with Pennyblackmusic.

PB: Does ‘Silver Rails’ have anything to do with the American train system?

JB: The American train system? (Laughs). No, it’s just that every time I do an album I’ve got to have a train in there somewhere. The train and the blues all go together. We’ve got to have at least one train, hopefully more, but that’s the one train that’s in there. But not the American train system. Why do you say that?

PB: There is an area in Missouri called Silver Rails, too.

JB: Oh, really? I didn’t know that. That’s just a coincidence, but a good one.

PB: Some of your most long-standing and creative collaborators burst forth in ‘Silver Rails’: Kip Hanrahan, Pete Brown, and Robin Trower. How did you get them on board?

JB: I was approached by a gentleman Mark Powell, who is in charge of Esoteric Records. He asked me if I wanted to do a studio album and, although I hadn’t thought about it, I thought that would be a great idea at this point in my life to make a studio album, a sideways look at what’s been going on.

The first song I wrote was ‘Drone’. I wrote the words to that myself and, of course, I had to have Pete Brown involved because we go way back to the Cream days and we’re a proper writing partnership.

My wife wrote the lyrics to ‘Candelight,’ the first song. Kip, we’re old friends, and I thought I’d like to have one from him too. So,he flew over from Virginia and we wrote ‘Hidden Cities.’

PB: ‘Progress’ from the 2003 ‘More Jack Than God’ album is a beautiful piano-based ballad. ‘Reach for the Night’ reminds me of that one. It sounded like you were literally in my living room playing the piano.

JB: It’s very much like that really because Pete Brown wrote the lyrics for that on a flight from Germany back to England. He just emailed me the lyrics and then I just kind of assembled it. It came very naturally. I tend to think of it as a kind of Chandler-esque look at the darker side of my biography. It was that kind of vibe to me, a little bit noir.

PB: You and Robin Trower go way back and have done multiple albums together.

JB: I wrote ‘Rusty Lady’ which has that real rock-blues riff and I thought, “I’ve got to get Robin to play on that. I hope he’ll be able to do that,” and he agreed. He was very happy to come along and play on that.

PB: Was that song about a car or a drug habit?

JB: No, that’s about the death of Margaret Thatcher. She’s the rusty lady. She used to be the iron lady. Now she’s a bit rusty, I think.

PB: ‘Drone’ is a great arrangement but when I first heard it I thought that it didn’t sound like Jack Bruce.

JB: It is. It’s not another cartoon. It’s me. When I was first thinking about the album, one of my sons played me a band that he’s been listening to called Om (Experimental drone metal band from San Francisco - LT) and another band called Earth. They’re young bands, really just sort of starting out, and I was fortunate to find out about them through him, and I thought it would be kind of hip, kind of nice to be influenced by the kids instead of the other way around.

PB: That’s a cool idea.

JB: So, that’s really what that’s from. I’ll take inspiration from wherever I can get it. It will be a bird’s song or a little bit of this or that. So, that one is very much from that younger generation of bands just starting out.

PB: Speaking of strong influences, your son, Malcolm, is in Sons of Cream, which performs Cream material.

JB: That’s right. At the moment he’s doing some dates with that band, yeah.

PB: And are you enjoying hearing their versions of those tunes?

JB: Well, I haven’t actually heard that band. And he’s not actually working with Kofi Baker anymore. (Kofi is the son of former Cream drummer, Ginger Baker - LT). No, Kofi’s in the States. They’re touring Europe and, for whatever reason, don’t ask me, Kofi’s not involved. I think there might be a little bit of history repeating itself. (Chris Page currently plays drums in Sons of Cream, with Will Johns on guitar, and Malcolm Bruce on bass and vocals - LT).

PB: Phil Manzanera from Roxy Music guests on guitar onthe album. How did he get involved?

JB: A couple of years ago, we were both invited by some Cuban musicians to go over there and do some playing. We went there with our wives and had a fantastic time. The people there are so warm, and when I wrote the song, ‘Candlelight’ I thought that if Phil could play on that then that would be a dream because he’s one of my favourite guitar players, and he just fits it right in that little island vibe that’s on that track. Like everything and everyone else, it just fell into place; like it was meant to be and you can’t argue with that.

PB: One reviewer called ‘Silver Rails’ a prog rock album. I don’t agree. I think ‘Hidden Cities’ has that prog rock feel, but I think it’s overall a very diverse album.

JB: I think it’s more of a Jack Bruce album. I often say I don’t play jazz, I play Jack. Really labels are difficult because, yeah, I would say ‘Hidden Cities’ is my version of metal. I imagine it as something Jimi Hendrix might be playing nowadays if he were still around, without being too presumptuous.

I think you’re right. You’ve got it. You’ve hit the nail on the head. It’s diverse and that’s what I’ve always liked to do. I think this album is about the most successful in my point of view that I’ve ever done because quite often it changes going from one kind of style to another - that can be quite jarring and quite difficult to do smoothly but I think this really works from one track to the next. It doesn’t feel forced or anything. Also I’m interested in all different kinds of music, so in my solo albums I like to show that.

PB: ‘No Surrender’ and ‘Fields of Forever’ were rockers. How did you create your parts?

JB: On ‘Fields of Forever,’ that’s me playing piano. I just thought, “What do we need for this album?” We definitely needed some pop/rock songs, and I just sort of wrote it. It was immediate. Sometimes that’s a really good source of inspiration. I needed it.

‘No Surrender’ just had to be there as the last track. It’s just a little statement saying ‘Don’t Give Up’ because that’s the advice I always give to young kids. That’s the best advice I can give, as a musician. Don’t give up and get a good lawyer.

PB: ‘Don’t Look Now’ seems particularly autobiographical.

JB: I think lots of the songs are autobiographical. But a lot is common to most people; it’s just called life.

PB: You reference, quite frankly, everything from marriage to the pressures of performing onstage.

JB: There was certainly a lot about getting married, maybe getting married too young or something, the first time around.

PB: I just spoke to the director of a local School of Rock. In their programme, kids learn a number of early Cream songs because they are “rhythmically challenging.” He said that when he put a group of kids, who didn’t know each other, in a room and asked them to work out ‘Sunshine of Your Love,’ they were surprisingly focused. Now when you formally studied music, it sounds like you were ridiculed for studying jazz. What do you think of this approach?

JB: I think it’s really wonderful that those young kids would be interested and want to do it and learn from it. If you want to learn, it’s good to go back to the source and even further back, obviously, than people like me or Eric or whatever. You can go right back to the Delta and beyond, whatever you want to do, but it’s really good.

A lot of people think that music started with Justin Beiber or something – nothing against him. It did start a little before that (Laughs). But I think if you want to play, it’s good to know the roots of where the lyrics are coming from. No doubt that ‘Sunshine of Your Love’ is a very good thing. I’ve heard kids play that. Quite often, it’s the first thing they might try to play on the guitar or the bass and it’s a good place to start.

PB: You have an excellent teaching video in which you talk quite intimately about playing the bass, and then you show your band performing the related song. You discuss being influenced by everything from Bach to Indian music. Should students study such things now? Should they go out and play first?

JB: It’s good to always be trying to do your own thing. But again, nothing comes from nothing. Go back to the roots. Find out where it comes from. Study that just like anything else. But the important thing, really, is to come up with your own ideas, your own takes on things, and your own version on things because that’s the way music or anything else progresses. It’s nice for music to progress as opposed to stand still. So, yes, I’m all for it.

PB: How did you create the one-off ‘Theme for an Imaginary Western’?

JB: That’s Pete Brown. I have to give him kudos for writing the lyrics. The music was something I had been kicking around for years. I never really knew what to do with it, and then during one of our writing sessions we were really under pressure to write an album.

Pete came up with that beautiful take on a western movie, something like the Seekers or one of those great movies with John Wayne in it. I think the lyrics are really beautiful and a lot of people love that song.

PB: Are you still involved with Spectrum Road?

JB: There are a few things with Spectrum Road that we’ve put together. We know it isn’t possible to play for long tours, but we’ve managed to play every year for the last five years. We managed to play in Japan two years ago. We also played in Europe two years ago. We missed last year, but we’re looking for a space where we can all get together and play and maybe we can get together in Britain this time around, this year, hopefully.

PB: The aim of that group is to celebrate the work of the late jazz drummer, Tony Williams. Why has Tony Williams been such a strong influence?

JB: When he started out, he just turned the whole drumming rhythmic thing around. It was just incredible. He was just a kid. I mean, he was a little older than me, but when I first heard him I think he was about seventeen and already playing with Miles and Eric Dolphy and that was the music that I was into at the time. I was into this free jazz and blues-based jazz. He was a huge influence on people of my generation.

Then younger people, like Cindy Blackman Santana, just picked up on Tony. Tony was part of the great tradition of American jazz drummers probably, starting with someone like Baby Dodds and carrying right on through Elvin Jones to Tony, and, I think in a way, Tony was the last example of that kind of genius in American music, and to be able to play with him was such a gift, such a joy, in the same way it was to play with Eric and so on. To get a chance to play with those brilliant people, I’ve been blessed.

PB: When I see videos of your performances, I notice that you interact with the lead guitarists in a way that other bass players seldom do. You engage in a call and response with them as though you are also playing lead guitar. I think you created that.

JB: Yes, probably. That is what I was trying to do. But I think when you’re playing improvised music – I mean, in ‘Silver Rails’ the songs are already written but there is a certain amount of improvisation in there - it’s just like a conversation. I just think of it as a team of equals just having a little chat. What you’ve got to do, mostly, is listen. If you don’t listen, then you’re not going to get very far (Laughs). So as long as you keep your ears wide open, you can’t go wrong.

PB: How well versed do you need to be to get to that point? For many musicians, really listening is really difficult. Don’t you need to be fairly proficient technically before you get to that point where you can really listen?

JB: Yeah. I guess you’ve got to forget about the playing part. The playing part has got to be completely natural and it’s got to be what you are; an extension of you or part of you and then you can take it to that level. I guess that’s true.

PB: What combinations of musicians work well for you now?

JB: When I’m touring, I like to tour with, I call it “my big blues band” although we don’t strictly play blues. That’s a great eight-piece band, and it means I can play piano because I’ve got another bass player. That is great fun. What I liked doing, really, on ‘Silver Rails’ is just having those kinds of combinations. The rhythm sections, with a couple of exceptions, are the guys from my Big Blues Band: Frank Tontoh on drums, Tony Remy on guitar and myself on bass obviously. And we know each other’s playing so well, so then you can just relax.

PB: Has performing changed much over the years for you?

JB: When we started out in Cream, playing all over the States, there were no rules. We didn’t know what we were supposed to do, so we just made it up as we went along. We played sometimes at baseball stadiums, and with very few people looking after us, just four or five people, so we didn’t know how to do it. We just did it.

Now it’s much more professional. But when it comes down to it, it’s basically the same thing. You’re travelling, and then you’ve got the joy of the performance, and then you’ve got to get to the next place.

It doesn’t matter what level you’re doing it on. It’s still travelling. That gets harder. That definitely gets harder as you get older. It gets physically more demanding. Two years ago, I was all over the world from South America to Japan to the States, Europe, everywhere, and I thought, “I’m just going to slow down a little bit” (Laughs). I’ve done all of that for so long. I’m not retiring, but just want to play a little less and do a little less travelling. Then it’s more enjoyable for everybody.

PB: Your daughter Kyla is doing a documentary about the making of ‘Silver Rails’.

JB: She just recently showed us the finished project and, obviously, I’m her dad, but she is very talented. She’s got a master’s in filmmaking and she graduated top of her year, but apart from that she’s made a few films now and she very graciously agreed to do that for me, and what a great job she’s doing of it.

PB: What makes the creation of this album unique as opposed to your other albums?

JB: About all of my family is involved, my children, my wife; as I said, she wrote the wonderful words for ‘Candlelight’, so that’s one of the nicest things and it’s never happened before. Everybody’s got a part to play, and it’s a really nice thing. That makes it unique.

Also recording at Abbey Road was very special with the in-house producer at Abbey Road, the fantastic Rob Cass. I was very, very fortunate to get to work with him. It just made for a very joyful experience.

PB: Had you worked at Abbey Road before?

JB: Over the years I worked quite a lot at Abbey Road, but right now it’s been a perfect time for me.

PB: How did you feel about the documentary done about your life?

JB: There hasn’t been a proper one done yet, I don’t believe.

PB: So, if one were to write a screenplay about your life, where would they start?

JB: Start at the beginning. I don’t know. You could start at the Cream reunion. That would be a good place to start and either work backwards or forwards or whatever.

PB: How did that go for you?

JB: It was good. It was great. Loved it.

PB: You moved around about fourteen times when you were a child. How did that affect you?

JB: I think it made me quite rootless. It made it quite difficult for me to make friends, as well, because I changed schools so often and I didn’t have friends right through primary school. I made some really good friends by the time I got to my high school. I think it made me feel a bit rootless, and then I left home at seventeen to start making my way in the world. I guess it led to that.

PB: Your UK tour has been delayed. Will you tour ‘Silver Rails’ in the near future?

JB: I am hoping to redo a lot of the dates that I haven’t been able to do this time around. So, people should keep looking at the website and Facebook. I guess it should say on there, later on in the year.

PB: Will you be concentrating on ‘Silver Rails’ as well as some earlier tunes?

JB: I want to play most of ‘Silver Rails’ because that will sound really good with my band. Playing it live, it will be slightly different, but I think I can do just about all of the tracks. And, of course, people want to hear the old songs too. And I enjoy playing them so I’m going to play ‘Sunshine’ and ‘White Room’ – it’s got to be done.

PB: Thank you.

Band Links:-

https://www.facebook.com/JackBruceMusi

http://www.jackbruce.com/2008/

https://twitter.com/jackbrucemusic

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jack_Bruc

https://www.youtube.com/user/JackBruce

Picture Gallery:-