published: 25 /

5 /

2013

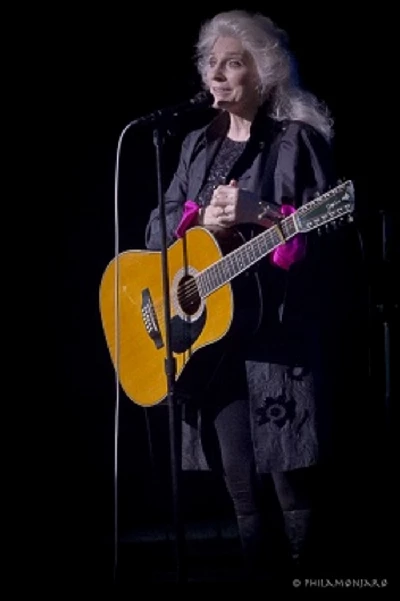

Lisa Torem chats to 60's folk icon Judy Collins about her musical heritage and work with mental health charities

Article

If this grand dame were a Scrabble board tile, she would be a triple word score. Everything the legendary Judy Collins attempts, she does to the fullest. From the infancy of her early 1960’s folk years, where she sang flawless and expressive covers penned by then little known artists like Leonard Cohen and Joni Mitchell, through her development as a full-fledged songwriter and, ultimately, after many dedicated years to Elektra, designing her very own label, Wildflower Records (her 1967 album, ‘Wildflower’ reached No 5 on Billboard charts and launched her songwriting), which encourages emerging artists, Collins has created a maelstrom of evocative music, inspired by Broadway’s Stephen Sondheim, Belgium’s Jacques Brel, Greenland’s whales, Jimmy Webb’s harsh moon mistresses and her ancestors’ plaintive lullabies.

Even personal tragic loss has inspired Collins to forge ahead, educate, instigate dialogue and heal others. She has facilitated countless mental health workshops and worked tirelessly with UNICEF. Her long fingers, once targeted by conductor Antonia Brico for a career as a classical pianist, are still tools of deep expression, but generally used for arranging her classically elegant arrangements.

In an interview with Pennyblackmusic, Collins celebrated her heritage, her loved ones, her repertoire and her commitment to use her talents and intelligence to create a greater, more caring world.

PB: I was listening to songs like ‘Gaelic Lullaby’ and ‘Bold Fenian Men’, and heard that extraordinary lilt in your voice. I was wondering about the Irish influence and how you channeled that.

JC: I surely did. My father sang all of those Irish songs, and so when I started to sing folk music and began to explore the myriad of songs that come out of the Irish tradition I realized that I know a lot of them. I grew up with them. My iPhone went off while I was driving uptown today and it played ‘Patriot Game’, which the story of Ireland and England and a very dramatic song.

I’m going to be going to Ireland on Sunday for some press, and then I’m going to go back mid June to do a handful of shows, and I’m going to get an honorary Irish-American Foundation induction into that organization in Dunbrody. My co-recipient is J.F.K., and the celebration is amazing. They’re bringing the eternal flame over, and the Kennedys will be there. I think Jean Kennedy Smith and Caroline Kennedy Schlossberg are both coming, and this is a big deal for Ireland. It’s the 50th Anniversary of when J.F.K. was there, so I’ll be part of that, which is amazing.

I’ve always been around Irish music. I’ve always sung it. I’ve always loved it. I’ve always been interested in it and passionate about it (Laughs). I wish I could sing some of those political songs, but I don’t think it’s very appropriate to do so. First of all, I don’t live in Ireland even though I’m Irish and feel passionate about that, but I’m also English so it kind of puts a cramp in the style if you try to sing for Ireland and you’re actually English as well. Anyway, I certainly have the Irish background and I certainly heard songs from the horse’s mouth.

PB: You have a talent for choosing covers tailored to your voice and yet your material is so diverse: ‘Drops of Jupiter’ by Train, ‘Pacing the Cage’ by Bruce Cockburn, cerebral ballads by Stephen Sondheim, Jacques Brel and Sandy Denny. What’s the secret?

JC: I think I learned that from my father. I think he had great taste in songs and, of course, he also covered the gamut from the Irish and English and Scottish ballads through all of the great American songbook repertoire, plus he wrote his own songs and he had his own radio show; so he was singing every day, practicing every day, setting things to music like Don Blanding’s ‘Vagabond’s House.’ He would set that to music and then perform it, and everybody else would be just in tears at the end. He was a marvelous interpreter of songs, and he always chose the best songs, and I think that that was how that all came about.

I don’t care where it came from or what it says, in a way, although I won’t sing a song that doesn’t suit my linguistic needs – I can’t sing a crummy song or a song that’s poorly written.

For instance, I was standing in the observatory in Nashville, three or four years ago, and I was getting ready to go and sing in a circle. It was summertime. Everybody was outdoors. There was a piano there for me and then a couple of other songwriters, including Amy Speace, who wrote a wonderful song called ‘Weight of the World’ with a man named John Besner. John was there, but he had a terrible cold. There was a guy who had come there to step in for John, in case John couldn’t sing; he was unable to barely speak. And while he was standing in the rotunda of the observatory I heard this guitarist start this song, a Spanish sounding guitar and I heard just the opening chords, and I guess I heard him sing, “Dah dah dah dah dah dah dah…,” and I said to Katherine, (Judy’s manager_Ed) who was with me, “Oh, my God, I have to learn that song.”

I hadn’t learned the words, I hadn’t learned the song. Michael Johnson - that is his name - sang the song because John couldn’t go on, and I said to Michael afterwards, “I have to record that.” He sent me a tape of it, or an MP3 (Laughs), in today’s lingo, and I said, “I want you to sing this song and I will sing harmony with it,” and so that is what we did.

And it’s a song, which I’ve got to put in my repertory because ‘Amelio’ is a fantastic song, and somebody said to me the other day, “Why are you not singing this song?” So, I’m going to start learning it but, in a sense, you know the minute the thing starts – you know where it’s going to go, and you know it’s going to be right or you know it’s not.

PB: The story I heard was that Leonard Cohen sang ‘Suzanne’ over the phone to you.

JC: No. He gets his stories mixed up. I have to give him credit. He’s brilliant, but he gets his stories mixed up. He came to see me in 1966 because our friend Mary Martin had turned us on. and he wanted to find out whether I thought he wrote songs. So he came to see me and the first day he didn’t sing me anything, which is really amazing.

He came back the next day and he sang me ‘Suzanne,’ ‘Dress Rehearsal Rag’ and ‘The Stranger Song.’ In a few days, I called him up and said, “I have to sing ‘Suzanne’.” Then, of course, he sent me the little tape of it and so on. It was Joni Mitchell, who sang me ‘Both Sides Now’ on the phone, and he gets mixed up. Never mind, it’s okay.

And so he sang me these songs, and I started recording them, and they were on my sixth album, so by that time Elektra was really getting its act together. They were really doing the marketing properly and pretty soon everybody knew the songs of Leonard’s, as well as the other songs on the album.

And then he said to me, after I had recorded a half dozen of his songs, “I want to know one thing.” He said, “This is great. You’ve given me such exposure and I have a record label and I’m getting to be well known, but how come you don’t write your own songs?” And I went home and wrote ‘Since You’ve Asked’, and I’ve been writing ever since.

PB: Speaking of your original music, I wanted to know more about ‘In the Twilight.’ My father had Alzheimer’s Disease and that song touched me greatly, as I’m sure it did many others. I marvel at the way you described in great detail your mother’s full life with lyrics like “the Chardonnay in the crystal vase.” At what point in your life, did you write this song?

JC: I was about to go to Florida to do a concert and I visited my mother. My mother and I were just incredibly close. And although she was in Denver, I was in Denver a lot, working there on and off, and I’d come for vacations and we’d always spend time in the mountains. So we had a lot of time together, and when I would go there it was always with her. I had gone through the routine of finding her this gorgeous place, assisted living, which was about three blocks from where she had lived for 70 years.

I was on my trip and had gone to see her. She and her husband were still there. As I left, she said, “Have a wonderful concert tour down there,” and one of the caregivers, a wonderful woman named Katherine, said to me, “Your mother is such a lady,” and I said, “Yeah, she really is,” and as I left, I thought, “She’s in the twilight.”

I got to Florida, and just a few days later I got the call that she had had a stroke and was gone. I had written down, “She’s a lady,” and I’d written down, “In the twilight.” “She’s a lady in the twilight/She sleeps most of the day.” So, as soon as I got back from Florida, we had the funeral to do and the memorial service, and by the memorial service I had written it, and I actually sang it, a cappella, at the memorial service. And she was a lady and she had an incredible life – astonishing, really.

PB: A relative said, to me, in the nursing home, that you can not just remember the painful last few days of a person’s life, you have to remember their whole life. That’s what ‘In the Twilight’ brings across so well, that acknowledgement of the whole person.

JC: I wanted to tell about this woman and her nine and a half decades of being on the planet, some of the things that she saw and some of the people she loved.

PB: It’s a beautiful tribute. In your last album, ‘Bohemian,’ there are a lot of place references. One of the most memorable is ‘Morocco’. Were you there?

JC: No. I woke up from a dream one day and wrote that first line down. “I dreamed that I saw you once down in Morocco/Your clothes were so old, they were new.” I wrote it down in my songwriting notebook. It must have been at least ten years before I finished writing the song.

It was the same thing for ‘Big Sur.’ I had a series of lines. This is what I do and then I collect them, and see if I can shake out a song from what’s gathered. Either I do that or I sit at the piano when I’m home on a regular basis and see if I can shake them out of the piano. They seem to be already written by the time I sit down if I’ve gotten a hold of those first couple of lines. Of course, a lot of it is from travelling. I do so much of it. In some places, the images are so strong.

PB: ‘Big Sur,’ too, is a real traveller’s song.

JC: Yes, it is. Been there a lot.

PB: Your piano teacher, Antonia Brico, wanted you to be a concert pianist, but in many ways you still are. Your piano arrangements are gorgeous. Do you come up with those arrangements separately or as part of your writing process?

JC: It is part of my writing process. It all comes together. When I write, I’m sitting at the piano, usually noodling and the songs usually come out together. First of all, I always sit down and play my exercises. I play my Czerny and my Hannon. So I get my fingers ready, and then I noodle and I pull out my songwriting books.

I just spent the morning cleaning out my studio. Oh, my God. I can’t work in it unless it’s really clean and together and ready to roll. So I finally got at it. It’s been a mess lately because I’ve been away so much. I’ve been kind of throwing things at it. So now it’s ready for me to launch into the next phase of songwriting. There’s a whole bunch of stuff that’s got to get finished.

PB: You sound very disciplined.

JC: I am. I have to be for what I do. But perfectionism is so dangerous. You have to really be aware of it because I cannot do everything. I want to do everything. I want to be everywhere with everyone, doing all the things that are interesting and fun and I want to live like a monk. They’re mutually unattainable. You can’t have both all of the time.

So, if I’m tired, I don’t accept that very easily and that’s ridiculous. Of course, I would be tired. I do all of these shows every year, and I travel like a maniac all over the world. So, if I can’t be producing things all of the time, it makes me crazy.

PB: Let’s talk about your other writing. You wrote an eloquent essay, published in ‘The New York Times’, about the closing of the Russian Tea Room there. It sounded like it was a second home for you. Have you found a replacement?

JC: Not really, no. There’s nothing like it. There are places that try to be like it and, because it was closed and it was under other management, we had high hopes, but they’ve ruined the menu. They haven’t changed anything inside. The décor is the same, and the first floor is wonderful; filled with all of the paintings and wonderful light. It’s very special. We try. We go there once in a while for Christmas Eve, but I had to find other solutions. Nothing compares to what the Russian Tea Room was, not the menu, not the ambience, nothing. It was spectacular.

PB: Judy, you’ve written several books and a novel. Is writing cathartic for you? Also, when do you know when you’re finished with a work?

JC: Well, I’ll never be through writing. I’ve got two books going now and I will get one of them done, or out or bought or I’ll publish it myself or something, but I have to be writing. I always kept journals for my whole younger life; I don’t do it so much anymore but I still try to catch up and keep up. Now the paperback of ‘Sweet Judy Blue Eyes’(Collins’ 2012 autobiography of her life in the 60’s - Ed) is out, and I’m going to be working on developing a movie from that book because it is a fascinating time, a wonderful time, and the only thing I have to say is that there is lots more to write about.

I have other subjects and other ideas, and I do want to write another novel. The second work that I’m doing is the story of my father’s life but told in his voice, which has been very interesting. That might be the window through which I might turn it into a novel, because it’s certainly worthy. His life was a novel. It was incredible. That might be the place I need to dig a hole in and really find my way through to turning that into a novel – a historical novel, in a way. It’s a historical piece whether it’s first person or written as a historical novel.

And then the other one is about my food addiction. That’s about an eating disorder and its progress through life. People don’t talk about that subject too much, and they often don’t know about it too much. So, those two subjects interest me a lot, but there are other things. I have to be writing for the most part for a good part of the year, not the whole year, but I have to be in that group.

And whether I continue my journals is another question. That also is a source for a book, itself. I’ve quoted from my journals, but I’ve never issued a collected journal volume, so to speak. And, also, all of my song lyrics have never been collected in one place, so that might make an interesting journey, to put the lyrics in the journal sections where they happened. A lot of my friends are writers, so I’m sort of around that world, and it’s too interesting for me to drop out of. (Laughs).

PB: Your father, Charles Collins, was blind. Do you feel this impacted you as a child? Did it make you a more compassionate person?

JC: It was a very powerful influence. It certainly taught me about differences in people, and what other people might have to put up with that I didn’t know about, and things that I had to put up with that other people didn’t know about, and I suppose that is a source of compassion. He was so compassionate. He was so insightful about people and so eager to learn about the world, to absorb and read everything he could get his hands on. I think that imagination and curiosity of his was a great educational tool for me.

PB: You went on to work with UNICEF and facilitate mental health awareness workshops as an adult. What has this meant to you?

JC: I started writing about suicide after my son’s death in 1992. I wanted to write a book about suicide. My then publisher said, “No, people don’t want to hear about that from you,” so I sort of slipped it into a book called ‘Singing Lessons’ which was published in 1997. But I didn’t really do what I wanted to do, so then I found a publisher who was willing to go the whole nine yards. I wrote ‘Sanity and Grace’ which is all about suicide. It’s about what I’ve experienced in my own life with depression and my own suicide attempt, my son’s suicide, a kind of a personal view of where it lies in my life and it’s a brief history, I suppose, because I do refer to a lot of people’s ideas about suicide. It was a great education.

It’s a terrible thing to deal with; it’s awful. You certainly don’t want to go there unless you have to. But when you have to, you find the literature. Now you find a body of literature that really spans. My living room has a shelf that is devoted to all of the books that I worked with while I was writing this book, and I don’t think you would be unable to find these books in the library today. But going down the line: ‘The Legacy of the Heart’, ‘In the Midst of Winter’, and ‘Stronger Than Death’… Suicide is humanity’s single most compelling, philosophical question.

Suicide is different than other losses. You can’t apply the same logic or reason. I started to get bookings for fundraisers for mental health events. I even spoke at Harvard to the psychiatric school. I was amazed because I don’t believe in drugs, and most of these people are drug peddlers from the word go, and they want to treat you with drugs no matter what happens to you. I was surprised they had me in there talking about my alternate homeopathic and naturopathic solutions.

I asked my mother to come to this big fundraise for a suicide prevention group. It was at the Marriott Hotel in downtown Denver, and she looked around the room and said, “Oh, my God. Anybody who’s anybody is here tonight.”

I said, “You didn’t know you had such a lot of company, did you?” Being part of a dysfunctional family, you don’t always realize that anybody else has the same problems.

I knew that that was the only way I was going to get through it. The first thing I started writing was a 24 hour day book for people who have suicide in their lives or who are surviving the loss of somebody, and that is what eventually turned into ‘Sanity and Grace’ a few years later. But I knew that I had to talk about it, and I knew that I would totally vanish unless I did.

PB: It must be very healing for people to read about others who have survived a loss and to feel that they don’t have to keep it a secret.

JC: In fact, if I keep it a secret, I’m going to be damaged in some way, and I want to be able to talk about it so that somebody else can talk about it too.

PB: And to keep alive the dignity of the loved ones as well.

JC: Absolutely. My son was so wonderful and had so many wonderful qualities. He was loving. He was kind. He was generous to everybody but himself, I suppose. But he was caught in that dynamic of having relapsed, so having depression in his life - he certainly inherited the gene for it, but it’s been an exploration that has had a tremendous effect on my own life in getting to be more exposed – just when you think something terrible has happened to you, you find out somebody has lost two kids to suicide. So it’s been a very important part of my life and it continues; besides talking about the mental health issues and the suicide and the alcoholism, there’s a lot to say.

PB: What was it like working with UNICEF?

JC: I was visiting children in land mine zones in Mozambique. They had the first real land mine education system starting in 1991. It was basically an art-based, art therapy recovery program for children and consisted of seven sessions, during which the children would be guided about their drawings, but they would then draw what was in their hearts and minds, most of all bombs and fire and devastation. And then by the seventh hour, they were painting the sunshine and smiling faces. It was really powerful.

PB: Thank you.

The photographs that accompany this article were taken by Philamonjaro at www.philamonjaro.com.

Band Links:-

http://www.judycollins.com

https://www.facebook.com/judycollinsof

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Judy_Col

Picture Gallery:-