published: 23 /

4 /

2011

Mark Rowland speaks to Curt Kirkwood, the front man with seminal country/ psychedelic/punk rockers the Meat Puppets, about his band's unusual songwriting influences and style of recording

Article

More often than not, musicians are not quite the people you think they’re going to be. A songwriter might be able to write brilliant, touching ballads, but they can be petulant, childish, even violent. Someone who writes happy, uplifting songs could suffer from depression. And conversely someone who writes morose, dark music will most likely turn out to be really funny, outgoing and sociable.

Curt Kirkwood is exactly as you’d expect him to be. His music is laid back, easy going, loose, and will drift off in all manner of unexpected directions, much like the man who wrote them. For the best part of thirty years, Kirkwood and his band, the Meat Puppets, have been producing albums full of well-constructed, intricate songs that somehow sound like they were jammed out in an afternoon. Each album incorporates a mass of different styles, and yet each has its own sound, quite distinct from each other.

It’s quite a feat to pull off once, but the band (Kirkwood, his brother Cris on bass, and Shandom Sahm on drums) are still doing it thirteen albums into their career. Their latest album, ‘Lollipop’, is full of great wonky pop songs, mixing 50's style rock n roll, Sabbath-like riffs, proggy keyboards, country, folk and even reggae, all delivered in the band’s laid back manner.

That the band can sound so distinctive when so many different styles of music have been incorporated into their songs over the years is testament to the quality of Kirkwood’s songwriting, which doesn’t always get the credit that it deserves. Perhaps this is down to the leftfield nature of the songs, but it’s perhaps more to do with his refusal to play the music business game. The Meat Puppets have always done whatever they felt like doing, even when they were signed to a major in the 90's and got plugged by grunge luminaries such as Kurt Cobain.

We speak to Kirkwood over the phone from a Leicestershire location where phone signal is temperamental at best. Our phone cuts out three times during the interview. As we get more and more frustrated with the phone, Kirkwood is characteristically unfazed by it all: “This is all I’ve got to do today, so it’s cool.”

PB: The new album is really varied. There’s even a bit of reggae in there…

CK: Yeah, every once in a while that seeps in.

PB: So how do you go about getting the songs to an album together? Do you tend to write them all at once, or over a period of time?

CK: Generally what I have is stuff that’s accumulated. That started a long time ago, around the second record, 'Meat Puppets II'. I started having a backlog, and that’s why 'Meat Puppets II' has some punk rock in there. It has some country, some sort of weird stuff and some ballads. I started trying to get away from just having a garage band, trying to get a little bit of my taste in there beyond what the band liked to play. Sometimes the songs don’t seem like they’re right, so they just go on the shelf, and in this case, there’s some on there that have been on the shelf for a good long time. Half my life.

PB: Which songs are they?

CK: The first song, 'Incomplete', I wrote when I was 25. No, twenty…24. I wrote that first song in ’83. It was right around the time I was doing 'Meat Puppets II', and it’s one of the things that didn’t fit at the time, and I didn’t get a chance really to do anything with it.

There’s a lot of stuff like that. The last song, ‘Spider and the Spaceship’, I wrote when I lived in Venice Beach in the 1990s, as well as…um…what else did I write then? Oh, ‘Way That It Are’ and ‘Hour of the Idiot’. They’re both from probably 2001. But this is pretty normal for me. I just get a bunch of songs together and try to figure out what goes. It’s kind of like a crossword that doesn’t make any sense.

PB: So how do you decide which songs to take off the shelf and dust off for an album?

CK: Oh boy, I wish I knew. Hold on a second. (Off phone) Hey shut up! Knock it off! (Back on phone) I’ve got a couple of big dogs. They bark at everything. There’s just some strange way that they seem to fit together, and a lot of it is honestly just consciously trying to get them to be dissimilar. For instance, with the first one on there, it’s like: "That’s kind of different. That doesn’t sound like anything I think I want to put on there." So we start off with that, set the pace in kind of an odd way, and then go to something completely different. I love the variety. I don’t care to hear the same song over and over.

PB: Most of your albums seem really varied, but at the same time, they seem like distinct entities from each other; 'Meat Puppets II' has a very different feel to 'Up on the Sun', for example. If you deliberately choose songs that shouldn’t fit together, what gives them a unified sound? Does that come through in the studio?

CK: For sure, I think that’s the thing that loosely ties it together the sonics of the record, the overall kind of vibe and the sound of it, outside of the construction of the songs. It can come from the tenor of the studio itself and the vibe between the band members. Also, we’ve never been able to go "Let’s write an album that sounds like this." We kind of get what we get. You can throw in variety and different techniques and all that stuff, but we learned a long time ago that aiming for things is kind of frustrating, for us, anyway.

PB: Your songs always sound quite loose, as if they’ve been jammed out, but they’re also obviously well-structured songs. Do you tend to spend a lot of time writing your songs?

CK: Sometimes, definitely. It’s not so much that I put the actual time in, say like ten hours a day type of thing, but time goes into it where I have to just leave it alone and wait for something else. You get the first bit of it, and then it’s like: "What do I do with this?"

Like ‘Shave It’, the third song on the record, I had the little jolly sea-faring intro (hums the first few bars) and I just sat around messing with it. I loved that little part. I didn’t have to do anything else to it. Just little by little, I’d go back to it. I have a little recorder in my living room, and just add a little bit to it, and, when the time came to go to the studio, I had to finish it because it was only half done.

There are a good number of things on this record too that are like that where we got to the studio. This time we didn’t practice any of it. We just set up the drums and started cutting songs with drums and acoustic guitar as simply as possible, just to make it rational as much as possible, and then we got to the impasse of "I don’t have lyrics for this," or there’s no middle part or something like that. So it’s like "Quick, write something up," which is kind of fun, to have your hand forced that way artistically, rather than endeavour. It’s just like you’re up against the wall, here we go. This is going to be it. And that’s appealing, that kind of works. I do that quite a bit.

I wouldn’t say that I work that hard on writing songs, I’ll sometimes be sat there for ages and think to myself, "God,I haven’t written anything in a year. I don’t know how to write, or how I do this." Next thing I know, I’m ripping off Black Sabbath or something, and there you go, I'm off. It’s odd how that works. I’ve never been the kind of person that can sit down and make myself write.

PB: A lot of songwriters tend to have their own methodology when it comes to songwriting, either starting with the lyrics, or a melody, for example. What’s your method if you have one?

CK: I’ll get a riff, or a chord change that I like, and a lot of times, that’s predicated by having a melody that goes along with it, just out of the blue. I’ll kind of hear something there, and I’ll find myself humming something. So then I flesh out the chord changes and the melody, slap some lyrics on it, and there it is.

In terms of actually what I do on purpose, the one thing I definitely try to do a lot of times is avoid saying anything like. You know how they say, "Just write about what you see, what’s around you, what you feel" and all that? Well I don’t do that. I don’t really like to. I like words, and I like writing English. I think it’s really fun because you can do so much with it, so simply, and it’s really fun to find something that doesn’t go in any direction, but still somehow makes a little bit of sense, and that’s subjective to the listener. That’s what I like to do.

PB: There is certainly a sense of the surreal about your lyrics. They’re also very visual. Are they just the result of random words thrown together?

CK: That’s the coolest thing to me, just stringing words together. Like you know how Burroughs did the cut-ups? I don’t really do that, but there’s definitely something to it, to just throw a word in there. Maybe the word sounds good. It’s a nice amount of syllables, and the way it sounds as it rolls off the tongue sounds good with a certain melody or something; that’s enough. We can worry about the meaning of it once we have a sentence.

I try to make the syntax kind of make sense, like you’re reading prose or poetry, and yet there really isn’t any sense.

The goal is to not just be completely surreal and cut-up. It has to be phonetically right a lot of times. I have to say, I’m pretty influenced by Lewis Carroll, for sure, but who else could write 'Jabberwocky', you know? Nobody else. I couldn’t do that. I’m kind of stuck with words that exist.

PB: ‘The Spider and the Spaceship’ has a sort of Carroll feel to it. Is that what you were going for?

CK: It really is about this chicken place that had this gigantic chicken out front. It’s right in the middle of Venice Beach, and that was the inspiration for that song. I was like: "Man, that chicken is cool." I never went in the restaurant, but nevertheless.

PB: Moving on to All Tomorrow's Parties, you’re playing 'Up on the Sun' at Animal Collective’s ATP in May. Is that the first time you’ve played a set comprised of one album?

CK: No, we only did it once before at another ATP. This will be our fourth ATP, in the last couple of years. We’ve really done a bunch of these. We did it at the second one we played in New York. We played 'Meat Puppets II', and that was harder really because that album is such a toss off. It really is. We had no idea what we were doing, and it sounded the way it did because of that. We’d made a couple of punk rock records, and then we’re suddenly trying to make songs that weren’t just pure inertia, and we wound up with that, but it was still very loose.

It was kind of hard to play in the original way. It was nearly impossible, but we know the chord changes and we did it. 'Up on the Sun' is a little more distinct – this is this and this is this – and we know a lot of the songs, for sure. There are a few that I have to go back over, and there are a lot of parts in there that are challenging, kind of remnants of listening to a lot of King Crimson and Yes and whatnot – Mahavishnu, Miles – just trying to be better musicians than we were.

PB: That album has a sort of wonky, prog rock Byrds sound to it.

CK: The Byrds, yeah I can see that. It’s kind of chimey, and it floats.

PB: Will you be adding any other songs to the bill, or are you under strict instructions just to play that album?

CK: I don’t think anybody would say that necessarily. Probably the chances are that we’ll do more like, say 'Up on the Sun'. We’ve been playing that one constantly for a long time and it’s becomes this platform for extrapolation, so usually 'Up on the Sun' lasts about 10 minutes these days. Or more.

It is the same thing with 'Lake of Fire'. We take some of these old songs, and they’re just kind of cool, repetitive things, so you can just take them out, which is what we’ve always done. We like to jam and just mess around, so maybe we’ll throw a little bit of that in there, but probably more towards the end. We’ll probably do it, like, play the album, and I agreed to do it on that principle. It’s like, it’s not my idea, and it’s what I signed up for. But I’m sure we’ll have time to mess around towards the end, or something. Kind of keep it intact, and take it out a little bit.

PB: How many ATPs have you played in England?

CK: This is the third one. This is the second one at Minehead. The other was at Pontins, over a different seashore.

PB: Camber Sands?

CK: Camber Sands, that’s it.

PB: So you’ve fully experienced the strangeness of the small, British seaside town, then? What do you make of them? How do they compare to what you’re used to?

CK: I like Minehead, I really liked it when we first went. Camber Sands was a little stark, and Pontins was like the Twilight Zone. That place is so immense and weird. We were there for three days, and that was our first one, so we wanted to check it out. There was a lot of just sitting around and going: "What the fuck?" and hanging out with Ween and messing around in the middle of the night.

Mickey broke both of his feet jumping over the wall there because they locked us in, and we wanted to go and find more booze. So Gene or Dean, whichever one Mickey is, he jumped out of the yard and he broke both of his feet. I don’t remember our set, or Ween’s set or anything else really. Maybe a bit of Hot Chip or something, I don’t know. Bon Iver, however, you pronounce it.

Anyway, Minehead is just, well, for one thing, you get to drive past Stonehenge, and I’ve been to England a lot of times and I’d never seen that. We didn’t know that we were going to drive past it. You know how that is. You’re just driving along, and it’s pretty there, then all of a sudden: "What the fuck, that’s Stonehenge, right?" That was like, holy cow, this is why we love to play music. It’s fun seeing all this stuff you heard about. I just thought it was a little amusement park, Minehead. The rooms were nice, the grounds were nice, and it’s a pleasant drive. I’m looking forward to it.

PB: Minehead is definitely one of the nicer seaside towns. It still has worn out little amusement arcades and things like that. How do you find all that stuff?

CK: Yeah, it’s odd, you know, I’d been to Dover on the ferry a lot, but I’d never been to small towns that much. My experience in England has been London, Leeds, Manchester, the bigger cities, and then really the only other time I’d been outside of that before ATP was back when, you probably remember when there was a hurricane that hit London?

It was quite a long time ago and in 1987. Ways back. We’d just played The Rainbow or something, and had tried to bail out to go down to Portsmouth, and it took us 17 hours to get to Portsmouth, because that hurricane hit. All these trees were falling over, and we actually got stuck on these little tiny roads. We had to get off the main highway, and we were following some dude with a chainsaw to weasel our way through these little roads. We actually ended up seeing a lot of cool stuff.

We begged shelter off this farmher with this nice manor and this nice old barn – that was when we’d been refused a few times, because it was like three in the morning, and it’s stormy like hell, and we were pounding on people’s doors, going, "Fuck, our car got trapped by trees and phone lines," which it did. We had to abandon it and wait for the storm to subside and go back and cut it out. It was crazy. So that was my only experience outside of the cities, really, at all, until these things. So this gives me the opportunity to go out and see a little bit. Cities are cities.

PB: I vaguely remember that.

CK: We got a copy of the paper in London the next morning, and there was this big colour picture of this huge fucking oak tree laying across a couple of cars, and these cops standing on the oak tree, just grinning their asses off (Laughs). You know there’s people smushed in there or something.

PB: What’s next for you after ATP?

CK: We’re doing Minehead and then we’re heading over to Dusseldorf and start about three weeks over there, and we’re doing Berlin, Amsterdam, Antwerp, a couple of dates in Italy, Vienna, Copenhagen, Hamburg, and we end it in London. Oh, and we go to Dublin too. We play at the Garage in London at around the end of it. Then it’s Dublin, and then we go home.

PB: Are you straight into a tour once you’re back in the US?

CK: Yeah, we’ve got two days off, and then we head back out to the West Coast.

PB: Touring always seems to be the most difficult aspect of being a working band. How do you find it?

CK: You know, it’s weird. It always kicks your ass, no matter what people think, unless you’re the type of person who can get on a bus and go to sleep straight away and get the right amount of rest. It’s really about getting sleep and that flip-flop schedule. We drive ourselves. We’ve rarely strung for the bus. That’s real expensive.

We’re a cut rate sort of an outfit. We always have been, since our early years. It just kills me to spend that kind of money, when I can just do it myself. So being that cheap, I’m pulling a double-shift. My brother and I do the driving. I tour manage. We have one dude, an old friend, who helps us lug crap around and helps us sell t-shirts and just fill in the gaps.

But it’s really just a double shift, and it becomes one long stretch. You get a day off and just try to sleep all day. What I found is that if you have a bus, you still end up staying up all night – the thing kicks off, you’re driving down the road, and it gives you the opportunity to drink, which I usually don’t do while I’m on tour. I usually don’t drink at all, but if I’m on a bus I’ll start drinking. So you get worn out either way. But it’s a mindset too. It's like it’s an expedition. We’re doing this. You know what you have in front of you, and it drains you. You’d be surprised what you can do. That’s how things get done. It’s never easy.

PB: So you’re basically touring in the same way you were when you started out?

CK: Yeah, we are right now. In the 1980s, we owned our own RV. It was an old piece of crap, and we’d live in it. We’d stay at state parks. And in the 1990s, the record companies would spring for buses a lot of times, when we were doing major label records, so we did that a little. But this is how we’ve mostly done it.

What we’re going to do in Europe is just take. We’ve got this band called the Dandies from Switzerland, who want to tour with us, so we said, "Have you got gear?", and they were like, "Yep," so we said, "Can we use your gear?" So now we can just rent a smaller vehicle and we’ll help them carry their gear. I don’t care if it’s other people’s gear. You can play on just about anything. It’s not going to hurt the show. We make it as simple as we can, and I don’t know what I would do if I made a whole lot of money doing this, and at times the money’s been better. I’ve never threw down for a light show or anything. Other people do it better.

PB: It really seems that you make the best of what you’ve got and don’t seem to worry about much at all. Is that basically your philosophy?

CK: It’s really fun to just go with it. I’ve always been into music. I don’t care about fashion that much. I don’t care about what people say about it: it’s not a show if you’re in your street clothes, or whatever. I don’t care. I’m playing for the kids in the audience. I’m playing for anybody who wants to listen, and I’m playing for myself. We’re playing music. The spectacle is what it is, and we’re not much to look at. If you need lights, go to an arcade.

PB: Thank you.

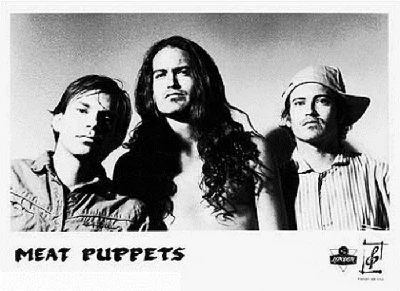

Picture Gallery:-