published: 6 /

10 /

2010

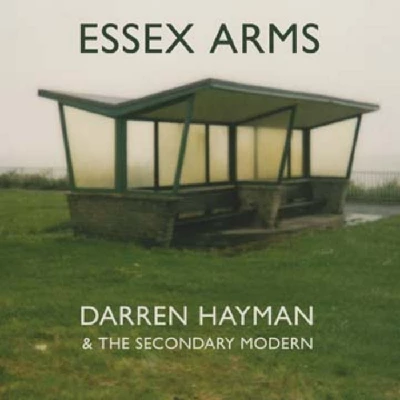

Former Hefner front man Darren Hayman in what is our sixth interview with him speaks to Ben Howarth about his latest album with his band the Secondary Modern, 'Essex Arms'

Article

I don’t think I’ve ever thought that Darren Hayman was particularly typical of your average lead singer in an indie band. The band in which he made his name, Hefner, were quirky – even by the standards of the late 1990s, when bands like Belle and Sebastian, Mogwai and Arab Strap were given the kind of free rein by the mainstream media.

Now, with a production line of thematic concept albums on subjects no other songwriter has ever even considered, he stands out as an individual in a music scene too often comprised of people who are well-meaning but ultimately unoriginal.

Since disbanding Hefner (they have reformed just once, to play at the tribute gig for John Peel, whose listeners had taken the band to heart), his musical output has charted otherwise unnavigated waters. After a series of EPs on the theme of traditional holiday venues (Eastbourne, Margate, Minehead and North Devon), he has now embarked on a trilogy of albums about Essex. Last year’s 'Pram Town', which told of life in Harlow, was acclaimed in 'The Guardian' and 'The Times'. Most said it was his best work since Hefner, but a year’s worth of repeat plays suggests it may have been his best work, full stop.

The follow-up, ‘Essex Arms’ takes the action to the countryside, to Essex’s dark heart of dog fighting and dogging, while revealing a previously unrecorded fascination with cars. His most naturally tuneful album, in places, it is also his saddest.

He’s had a busy year, albeit not a wholly happy one. An attack by a mugger after a show in Nottingham last year left him seriously injured in hospital, an incident that can’t have helped his growing dislike of playing live. But, he’s also become an enthusiastic user of twitter, an occasional blogger, while gaining much admiration for his wholly original animation for his latest single, ‘Calling Out Your Name Again’, a duet with Emmy The Great.

Asked about Twitter and his other extra-curricular activities, he says, "I suppose that this is a reaction to the need to promote myself. Its content, and everyone wants content. Some of it I enjoy more than other bits," he tells me "I do like Twitter. I’m not as keen on Facebook."

I meet Darren at his local tube station, and he drives me to his local pub. In tow is one of his cloest friends, Dave Tattersall – lead singer of the Wave Pictures. My interview has interrupted the pair’s chess game. At intervals, Dave chips in to our interview. Darren’s wife Helen also joined us and listened in and crops up in the text below as well.

He had quite a long wait, as this interview went on for quite a while. Though I was tempted to chop this up and make it shorter, I ultimately decided that the frankness of many of Darren’s answers justified publishing it almost verbatim (some of my more mundane questions have been given the chop). Anyone who balks at the length can content themselves with the knowledge that he has given several shorter interviews recently, all of which are but a google-search away.

"I think people are happy that I give long answers, but then they realise that they’ve got to transcribe it," he says. "I remember our last interview going on a long time. But this is maybe not how an interview should be... with your wife and your best mate listening in!"

I begin by asking him to explain the concept behind his newly released album, ‘Essex Arms’, which is the second in a proposed trilogy of albums about Essex.

DH: I did this album, ‘Pram Town’, which was a concept album about Harlow, a New Town in Essex, and I didn’t feel finished with it, really. Those types of songs carried on getting written, so this is another album about Essex. Instead of being about the suburbs, this one is about the countryside.

It is a disguised autobiographical album, in that it was written about places and the types of people I know, but it is not literally autobiographical.

Lots of it was written whilst I was doing walks in the countryside. Do you know those Pathfinder books? My wife and I have done all of the Essex walks and a lot of the lyrical ideas come from those.

I became very interested in a lot of the incongruous things, like a traffic cone or a bit of corrugated iron around a church – bits of the city that seem to have landed in the country.

There is a stereotypical idea we have of the country, of thatched roofs and Constable paintings, and I wanted to subvert that a little bit, and look at the lawless village that actually does exist.

Dave knows, Dave’s from a lawless village aren’t you?

DT: Yep!

DH: So that was the main idea. There was another thing I was trying not to do, although some people have said that I have done it, so I must accept failure in some way. But, I didn’t want it to be a social commentary. I didn’t want the songs to be a snooty middle class person looking down on the poor people. I’m singing about the sort of person I was before I got an education and about the sort of people that my friends still are.

I wanted to write about these people with empathy, which is a bit of a challenge, because these are the people who stage illegal dogfights in forests. I suppose it’s like the attitude, "Hitler was always nice to his dog." It never does anyone favours to caricature anything and I was trying my hardest not to do that. I also wanted to write a love story, about the kinds of people that don’t normally get a love story written about them.

PB: ‘Pram Town’ had a running theme, with a clear thread of a story hanging all the different tracks together. This album doesn’t appear to have the same approach.

DH: It’s not as character driven. With 'Pram Town', I mapped out a story and was very careful to make sure it made sense, although I wasn’t explicit about it. This has got a story to it, but... have you read any Paul Auster? In some of his stories he tells the same tale from multiple viewpoints, so it overlaps. This is a bit like that.

But there is a story. The story is that there is a girl and a boy who get together, they have lots of dirty sex in the forests and then she dies in a car crash and that’s it really. Not much of a narrative! But it’s a simple story, really, of falling in love with someone and having them taken away from you.

All that bullshit that I gave when 'Pram Town' came out, it’s a bit disingenuous really. That album was really about displacement, being in the wrong place. And, likewise, this isn’t really about Essex, it’s about love and loss. Essex is the framing device, just a way to present it.

I really wanted to use the word love a lot. The words "I love you" are in five or six of the songs, and I wanted to subvert that cliché a bit. Or, maybe, to prove that it wasn’t a cliché.

PB: I read an interview with you where you were talking about Dennis Wilson’s 'Pacific Ocean Blue' album...

DH: Yeah, it seems to me that Dennis Wilson, whenever he runs out of lyrics, he just says "I love you, I love you, I love you". I thought, that’s not a bad idea for lyric writing. We all do feel it, it’s true, and we do often say it.

PB: There are a few songs on ‘Essex Arms’ that end in big refrains, with the same lines over and over again.

DH: Particularly on the song, ‘Nothing You Can Do About It’, where I am constantly saying "I love you, and there’s nothing you can do about it." I was particularly pleased when I had that idea, of almost being a bully, and forcing someone to accept that you love them.

I think for that to work, the line has to be quite good, you’ve got to have five or six words that have a ring to them. Dave, do you have any songs that do that?

DT: No... (pauses)... I don’t think I do.

DH: I can’t think of any of yours that do that, actually. You should try it!

I think it can be like a close-up in a film. It takes the listener where you want them to go. I really like that line, and in that song, I wanted people to go away remembering that line. It also, mechanically, makes the song catchier.

If you repeat the same line five times, that is the song that someone will come up to you at a gig and say that they like, because you’ve just made them remember it.

DT: Is that the last track on the album? It’s the one that I’ve been listening to in the van, and I can remember completely, more than all the others.

DH: Also, we have been playing it for ages! Does it not feel like an old song to you?

DT: Yeah, I was surprised that one was on the album actually. In my head, that was a song from the album with your dog, Beulah, on the cover (‘Darren Hayman and the Secondary Modern’, 2007, his second solo album and the first to use his new group name – PB)

DH: I was playing it live long before Pram Town came out.

DT: I’ve played it with you, and the Wave Pictures haven’t been your band for ages and ages.

DH: Well, you know, ‘Genesis Rock’, which I played with you a lot, still hasn’t been released. It’s not on any of the albums.

PB: It’s on the live album, I think, the Darren Hayman and the Wave Pictures in Madrid record.

DT: Oh, of course. It’s the best song.

DH: (Quizzically) My best song?!

DT: Well, the one that was the best fun to play, maybe.

At this point, Darren’s wife rings, as she is about to join him in the pub. As she sits down, Darren asks, "Can I tell everyone what this T-shirt is about. This is actually one of the Hefner T-shirts. But when I ordered some to be made, she wanted me to get one without the logo. She likes the T-shirts without the logo on."

After this intermission, I move on to the next question.

PB: 'Essex Arms' is a first for you, I think, in that it’s completely acoustic, with no electric guitars or synthesisers. What prompted that?

DH: I get bored of electric guitars, what they represent. I mean, some electric guitarists are excellent. Dave is an excellent electric guitarist, and it’s not his fault... it’s the fault of... (thinks)... the Killers.

But I’m also trying to undermine the traditional view of acoustic instruments - that they have to be quiet. So I wanted it to be a robust, clattering acoustic record. But there’s not any intellectual reason for doing it – it’s just a framing device, again, a way to give the album its own sound.

DT: But you’re actually more interested in instrumentation than the lyrics, which is not what I lot of people think you’re like.

DH: Yeah, ‘Pram Town’ had some rules on it, I forget what they were. I’ve banned electric guitars from lots of albums, I banned them from the French’s album.

But the main reason for setting these rules is to give the album a feeling that the songs all come from the same place, although these songs actually come from a couple of different studios.

PB: You have a home studio. Was most of the record made at home?

DH: Half and half, this time. And when I say that, I mean half of each song was done at home. Dave and I both record a lot at Soup Studios in Shoreditch, underneath the Duke of Uke shop. Simon, who records there, is really good and is much better than me at recording a drum kit. But I know how to mix well, I think, so I do the bells and whistles at home.

The basic track is something you need to do with someone producing you, so you can concentrate on performing. But, when you want the cherry on the top, you can afford to spend a whole day over that. When I’m recording a home, I do things like the trombone part, where I can really indulge myself.

PB: That’s funny. I think a lot of the bands I have spoken to about to about this would record the bulk of their albums at home and then use the expensive studios for the fancy bits at the end.

DT: That doesn’t make a whole lot of sense! It makes a lot more sense your way round, Darren.

DH: I think Ben’s right, though, I think that’s how a lot of bands do it.

PB: I should stress that I really have no idea about recording studios, so I could be completely imagining that! But, to change the subject, you’ve now got a new label, Darren, with this album being released on Fortuna Pop, instead of Track and Field.

DH: Track and Field has stopped. They’ve just packed it in. Steve’s got a daughter, and has just decided that enough was enough. He’s been doing it for eleven years, so fair enough. I don’t understand why any of those guys do it really.

And Sean Price who runs Fortuna Pop and I have done stuff together before. He released the album that Dave and I did together actually, the bluegrass album (‘Hayman, Watkins, Trout and Lee’ (2008)).

PB: Did you spend time considering other labels?

DH: I did, actually, although is that not a little impolite to talk about in interviews? It’s not that I don’t want to be rude, but I don’t want to close any doors that might still be half ajar! But, and I’m not sure I’ve ever been in that situation before, I did have a choice of two. Both of whom were offering nothing! That was the bidding war.

But, it made sense. I’ve known Sean longer than I’ve been making records with him. I remember him giving me a big pile of Fortuna Pop seven inches when I was in Hefner. He managed to get backstage once!

I tell you what, put this in the interview, no one is busier than Sean Price! Busy people who go on about being busy, no one works harder – Mother Teresa, Florence Nightingale. But, he’s had a big success with the Pains of Being Pure At Heart, and he’s at that stage where a label possibly goes up a rung.

PB: Given how much of the work you do for the albums – selling them online and designing the sleeve art – and given that you have self-released the Hefner back catalogue, what do you get out of being on a label?

DH: I can do a lot of it myself, and I have this reputation for being a bit of a cottage industry. But, to be honest, I hate doing that kind of stuff. I can – I have a deal with a distribution company, and I know what you have to do to release a record, but I hate doing it. I want to write songs, that’s what I do. In particular, the bit that I really wouldn’t want to, that I would hate, is the PR and press promotion.

I suppose I will end up doing it. I recognise that it is the way that the music industry is going. But when the label is a good label and you like working with them, I prefer to do things the way they used to always be!

DT: (Interrupting, as he looks over my list of prepared questions that I am haphazardly failing to ask) I don’t want to spoil your interview, but is that not a rather brutal question?

DH: Oh, no, don’t spoil it!

PB: I’ll skip to it, and you can decide how harsh it is. With the French album – up to now, not really having any acclaim in the mainstream media - suddenly last year being the subject of a 'Buried Treasures' feature in 'Mojo', are you not tempted to skip over the reissue of Hefner’s 'Dead Media' album, and go straight to a CD reissue of the French's album ‘Local Information’?

DH: That wasn’t as bad as I was expecting it to be!

DT: I didn’t read the preamble. I just read, "were you tempted to skip 'Dead Media'?" which sounded harsh!

PB: It was in context!

DH: Well, stuff like that was really nice, but I don’t think that a page in 'Mojo 'is enough. Also, when I get to reissuing that album at some stage, I’ll still have all the pull quotes to use.

It was actually a genuine ambition of mine. I like Mojo, but 'Mojo' generally doesn’t like me, it generally doesn’t review my music. I’d always thought that I would love to be one of those artists that gets in the 'Buried Treasures' section. But, I kind of imagined I’d be fifty when I got it. And now that I have got it, I’m a little disappointed, because it means that I am now officially a slightly-cool failure.

PB: When I last spoke to you, in the month that ‘Pram Town’ was released, you gave the impression that you weren’t planning to play any gigs at all last year. In fact, you ended up playing as many as before, in several different towns and at festivals, and seem to be doing the same this year.

DH: Well, I don’t tour. The Wave Pictures tour. They’re away for ages. I do maybe three or four dates in a row, but I don’t tour. How long would you have to be away for it to be a tour?

DT: Maybe a week, at least.

DH: Well, I’ve never done a week. But, you’re absolutely right, I say every year that I’m not going to do any more shows that year, and I end up doing some. I’m saying right now that I won’t do any shows next year.

PB: Well, that would be a shame for the people that like your gigs.

DH: I really really hate it. I don’t hate being on stage, I love being on stage, but I just get very very anxious about playing live and that period of anxiety before I play live just gets longer and longer.

PB: Do you get nervous?

DH: Yeah. It’s not as simple as being nervous about going onstage. Its nervous about, where is the venue, will I get there, will the promoter pay, will the guys know the chords? It’s everything else.

DT: It's everything around the gig for you, isn’t it? You’re not nervous when you get onstage at all, are you.

DH: I think when I actually get onstage it’s a relief. I think its 45 minutes or so where I can forget all of that and I feel alright.

PB: Is it the fact that the gigs go well that means you end up agreeing to do more, despite, as you say, actually hating it?

DH: I use this word cautiously and people have always said that you should use this word cautiously, but I’m starting to think that I might be a little agoraphobic. I don’t really like travelling, I don’t really like going out. I prefer to stay indoors as often as I can.

And I know that for some people, agoraphobia is a terrible medical condition, it’s absolutely crippling, so I always feel bad when I say things like this.

But, what seems to be happening as I get older, is that it seems to be getting worse, this feeling before a gig. And, eventually I need to think of a strategy to get round it. It can’t go on getting worse. And at the moment, it feels like that amount of anxiety isn’t worth it, even for the fun of the actual gig.

PB: So, what about the ones that you are doing? You’ve been offered some interesting ones recently, in particular the shows at the observatory in Manchester.

DH: That helps, and if more of that came out of doing this interview, that’d be good. Doing a gig with a nice person, which you would think is the only ones you’d want to do, but it isn’t always so. Doing gigs with people that want to make it an event or where you’ve got a real interest in what the other bands are, or themes and strange locations. The show at the observatory, only 30 people can fit in, so we’re doing two shows in one night. When I spoke to the guy organising that gig, he put me at ease. It might not sound very good, like I’m saying I need to be pampered. I guess I am – pamper me, make it nice!

(Suddenly very adamant) I just hate rock music. And everything that goes with rock music. I just fucking hate it.

PB: Have you always hated it?

DH: No, I haven’t always. It started to occur to me that this was what I didn’t like, and then it grew...

PB: Was it a problem when you were in Hefner?

DH: Um, it was. John (Morrison, Hefner’s bassist and Darren’s partner in the French) always hated rock music as well. I understand that I do have guitar solos, I understand that I have people that bang the drums. But, when I say rock, I mean spelled R-A-W-K. Those clichés. And we all fall into them... Dave falls into them, I fall into them. People are just constantly trying to make you go down that path. So, to play shows in an observatory and to ban electric guitars and not play live, they’ve got to be helping me have less rock in my life.

PB: Is the show in the observatory the change to dust off some of the songs from the album you’ve often talked about, but not yet released, of songs about astronauts?

DH: I am thinking about that album a little bit more, lately. My motto at the moment is to finish things off, because I have too many albums that are unfinished. I think that I should turn my attention to actually finishing the album about astronauts.

PB: Do you not have the problem, then, that you end up with lots of albums finished before it is possible to actually put them out?

DH: Yeah, there is that. But still, I think it would be nice, creatively, for me to actually have finished off these albums.

(At this point, my cassette tape runs out, and while I’m faffing about trying to get another one to work, I mention one of my favourite songwriters Paddy McAloon, and his reputation for hoarding a series of albums away, all unreleased).

DH: I think he is quite unwell and I think it’s really sad. I’m always really attracted to those recent interviews with him and always read them. Obviously, I think he is a much more extreme case than me, but it resonates with me. He stands as a cautionary tale. He is a man in a room with loads of unfinished albums, who never goes out and plays live, who just finds it completely frustrating.

I’m not actually a fan, unfortunately. I like him, I think he’s really intelligent. I suppose I haven’t really given his music a chance. (Asks his wife) Are you a fan?

Helen: They’re my local band, I grew up about two miles from Langley Park.

DH: I think the problem for me is that he is very controlled and precise, he’s very clinical. If we had his story, but with songs sung on a broken three-string guitar, that’d be perfect.

He’s almost an exaggeration of me. I guess he’s got stage fright. He’s very anxious and doesn’t like going out.

I’ve heard a story where he sometimes looks for a song he has written, but he can’t stomach looking through all his old recordings for it, so he just writes it again, with the same title. It’s very interesting.

PB: I’m not sure how much unreleased music you have left over, but are you not tempted to just stick it all out in one bundle, perhaps like you did with the album of left over Hefner songs, 'Catfight'?

DH: I think the internet perhaps makes some of that easier, as it would be cheap and easy. But I don’t know. I tried to put together all the different versions of songs from 'Essex Arms', and that filled two CDs, with at least ten wholly new songs in there.

Then, there is a whole album of instrumentals I made last year. There are about seven songs finished for the astronauts album, and an album called ‘A Permanent Way’, of train related songs. I’ve written about three quarters of the next Essex album, which is about the Essex Witch Trials. Then, the next album that is likely to be released is called ‘The Ship’s Piano’, which has songs all written on my piano, which was a ship’s piano.

PB: So the next release won’t necessarily be the third in the Essex trilogy?

DH: I think the problem is that the Essex Witch Trials album talks a good interview. But I definitely don’t think it will be next. That album, and the astronauts album, have been perhaps a bit harder to write and it’s taken longer to bring the songs together.

You’ve got loads of songs unreleased, Dave. Don’t make it look like I’m bragging.

DT: Yeah, it’s a similar situation. It depends on what you count as unreleased or ones that I’ve left off. But, I must have 50-100 unreleased songs. I think the ones that I’ve actually released are just a small proportion.

DH: I think the question is not why do I have so many unreleased songs, but why everyone else doesn’t? Who are these people who seem to take three years to write ten songs?

DT: It’s not just people like Coldplay. It is all the bands that I’ve ever met, except a few of my friends. Even some very good bands who are very dedicated and very indie often write very few songs.

DH: There are still some very famous people who can write a lot of songs. Neil Young writes a lot of songs, doesn’t he? Paul McCartney does an album most years.

I’m not flippant about it, and I don’t write a song and think that it will do. I work really hard, and some songs might take six months. My songs go through loads of drafts and I pride myself on being an editor. But in those six months, I might write another thirty at the same time. I do not understand why people can’t write more songs, it’s really fun and really interesting. I know a D and an E sound quite good, and I bet there’s a new song in that.

I’m certainly not saying mine are the best. Sometimes the bands writing ten a year are writing better songs than mine... but that’s no fun, is it?

Helen: Mark E. Smith has that theory that there is no reason why a hard working band shouldn’t be able to do two albums a year.

DH: He’s right.

DT: It is particularly easy with his method, though, of just shouting over a band. But, I think a lot of people have a different idea of what a song is, that it is something altogether more precious than we think a song is. I think of a song as a little moment. Some bands seem to have a really heavy idea in their mind of what a song should be and I don’t like that way of thinking. To me, a song is like a picture.

DH: To extend your analogy, I think we’re trying to do interesting sketchbooks, while other people are endlessly re-touching their paintings. I think sometimes a sketch can be just as valuable as a painting.

But, you ought to remember that, relatively speaking, Dave and me are failures. And anyone who reads this will probably be thinking that.

PB: I interviewed you, by email, in 2000 when ‘We Love The City’ came out, and you said then that your ambition for that album was to make an album that was hard to dislike. Which strikes me now as an interesting comment, because it seems like a lot of the time, you are trying to make albums that you know only certain people would ever like.

DH: I can imagine saying something like that, and I think I may have said something like that before ‘Pram Town’ as well. But I’m definitely not saying it now. I’m writing some career suicide albums now.

But I don’t think that comment means I was doing anything deliberately commercial. My drummer, Dave Shepherd, said something recently that I agree with, and that is that I have a fear of prettiness and that I always want to upset the applecart with a certain arrangement or a synth line. I think that is maybe a criticism I have of myself, that I might sometimes be nervous that people might think of me as flimsy or lightweight if I make a song too pretty.

PB: Do you think that was part of the motivation for the big change that came with ‘Dead Media’.

DH: (Immediately) Yes. I think it sometimes happens on a small scale on songs, and sometimes it comes as a gesture on albums. I don’t think any of my albums are contrived, but I think on ‘We Love the City’ and on ‘Pram Town’ I wanted to make some albums that were nice to listen to. Whereas, if that happened on 'Essex Arms', it was probably by accident.

PB: There’s also a completely new theme on 'Essex Arms', which is the car theme.

DH: I was really pleased when I thought of it. Car songs are an archetype, right back to the Beach Boys, while cars were very important to teenage life in the place where I grow up and the economy in the South of Essex had been very reliant on Dagenham Ford. It’s strange that people haven’t quite grasped how much this is an album about cars.

PB: ‘Dagenham Ford’ is an interesting track. I saw it as a song that put the album in its local context, but I noticed an interview that you did with the SoundsXP site where they’d essentially asked for more songs like that.

DH: I’m pleased with that song, and I think that is one of the better songs on it. I like that guy from SoundsXP> It wasn’t a falling out. I just think he wanted more songs like that. But the point I would make is that if the image of shell suits and dogging is a cliché of the working class, so is the image of the noble working class who read poetry. I just think certain writers inject the working class with a nobility that is only there sometimes, but sometimes – like the middle class – they really are just thick and racist.

Songs just aren’t the place for discussing that. They are sketches, they are moments. They are not big stories. They aren’t even chapters. They are just a little paragraph. There is not much room for a story, because any exposition you give is going to quickly make the song fall apart. The best you can do is set a scene and give a few details that will hopefully make someone feel something.

PB: Thank you.

Picture Gallery:-