published: 24 /

11 /

2008

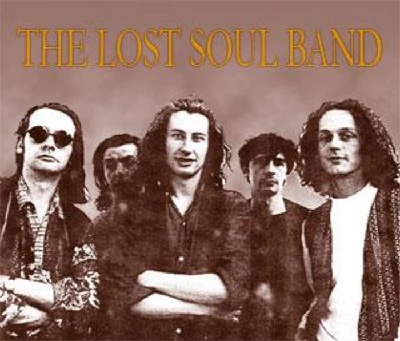

About to reunite for the first time in fifteen years Scottish 90's indie hopefuls the Lost Soul Band looked might make the leap from being cult indie rockers into the mainstream. In a two part interview, both of which we are running consecutively, singer Gordon Grahame talks about his band

Article

It has been nearly fifteen years since Gordon Grahame first left Scotland. In the time since then he has travelled widely, returning just intermittingly, and has lived in America, Paris, Andalucia, New York and Brighton. Even now though, as he speaks down the phone to Pennyblackmusic from his present home in London, his voice has lost none of the throaty burr of his youth, and his upbringing in Penicuik, a small former mining town nine miles outside Edinburgh.

Grahame is that rarest of things, a full-time musician. ‘You’re Lovely to Me’, one of the early songs of his current band Lucky Jim, was used in a national TV advert for Kingsmill bread, and the royalties from it have been enough for him and his family to live off for the foreseeable future.

While the Scott Walker-esque Lucky Jim has now recorded four albums, ‘Our Troubles End Tonight’(2004) , ‘Let It Come’(2006) , ‘All the King’s Horses’ (2007), 'True North' (2008) and has a fifth record in the pipeline for next year, 41 year old Grahame is on the phone to talk primarily about his earlier group, The Lost Soul Band, who are reuniting for the first time since 1994 to play two shows in Edinburgh and Glasgow between Christmas and New Year.

For a period of about a year between late 1992 and during 1993 the Lost Soul Band, which as well as Grahame (vocals, guitar) also consisted of Richard Buchanan (bass), Mike Hall (keyboards), Brian Hall (drums) and Gavin Smith (percussion), looked like they might make the leap from being cult indie rockers into a mainstream act.

A single, the world-weary mini epic 'You Can't Win Them All Mum', briefly touched the nether regions of the charts. There were also three albums. The first, 'Friday the 13th and Everything's Rosie' (1993), was a rabble-rousing country record, which the Lost Soul Band recorded in three days. Their second (but actual first recorded) album, 'The Land of Do As You Please' (also 1993), was co-produced by the group with name producer Callum Malcolm (The Blue Nile, Simple Minds), and, skipping across a rich gauntlet of styles, included Celtic rock tracks, Van Morrison-type R&B/soul numbers, raucous Sly Stone-style funk and folk torch ballads. The last, 'Hung Like Jesus' (1994), found the band dropped by Silvertone, their label, and reduced to a three piece, and was a discordant rock album.

The Lost Soul Band's rapidfire ascendency and sharp fall is a tale of both beyond-pragmatic musical idealism and defiance, and chaotic record company politics and ruthlessness.

PB : The Lost Soul Band was formed by yourself, Richard Buchanan and the Hall Brothers in in 1989. How did you first get to know each other ?

GG : Mike Hall and I had been in the same classes at school together in Penicuik, and Brian was his older brother. We met Richard a little bit later because he lived in Edinburgh and then Gavin joined the band last. Mike and I had dabbled in a few different bands together when we were at school, but Brian was a bit more serious. He was in the kind of bands that actually played live (Laughs).

PB : Were what you and Mike doing together up until the Lost Soul Band all bedroom projects then ?

GG : Yeah. Then we had a bit of a gap. I moved into Edinburgh and started playing a lot on my own in pubs. I was working in the civil service and Mike was at university as was Brian. I went around to Mike’s one night just visiting him. I hadn’t seen much of him for a while and I had just bought a Takamine guitar which is an electric guitar, but which sounds like an acoustic guitar when you plug it in. It was quite revolutionary at the time. All this cheap stuff had recently become available, and Mike had just bought as well a keyboard which sounded like a piano rather than like some kind of a synthesiser.

We just started talking about playing some music which was roots-based, but that you could play live and do justice to it which, without the aid of really expensive equipment, would not have been really possible before. That was the start of the Lost Soul Band.

PB : Your influences were largely rooted in the past. Obviously Van Morrison and Bob Dylan were huge influences. Your My Space site also lists other things as well like‘The ’68 Special' and ‘Electric Ladyland’ as being influences. You were about 21 or 22 when the Lost Soul Band formed in 1989. How did you discover those? Was it through your parents’ record collection ?

GG : No. My parents were much more into musical theatre and crooners and stuff like that. I learnt the guitar to write songs. I was always comfortable singing, but I wanted to learn the guitar, and then once I started writing songs with guitar I immediately wanted to buy records by people that just had done that.

At that point in time in the late 80’s there wasn’t really anyone doing that, so I would maybe see something like Kris Kristofersson on the front of a record and he would have an acoustic guitar in his hand. One thing generally lead to another. I was an obsessive record buyer. As soon as I would cotton onto one thing that was good in an era I would pretty much buy everything that I could get my hands on from that time.

PB : You released your first two singles, ‘Coffee and Hope’ and ‘Save It’ on your own Lost Oyster label. The Lost Soul Band played the Oyster Bar chain in Edinburgh a lot in its early stages. Did that name come in tribute to that ?

GG : Very soon after we got the band together we got management with a guy called Paddy O’ Connell . We had been doing really well playing the Oyster Bars and he got the Oyster Bar owners to stump up the cash for the first single. It was a token gesture giving the label that name.

PB : How quickly did it take for you to branch out from venues like the Oyster Bars into the rest of Scotland ?

GG : At the beginning there was this real rocket projection. It was really fast. The Oyster Bars very quickly became rammed and we moved up to playing slightly larger venues in Edinburgh like the Venue. It was just a case of the word getting around. The promoters in Edinburgh started passing on the word to the promoters in Glasgow and we ended up playing places through there like King Tut’s . It was quite fast.

We were still kind of slogging a bit in places like Aberdeen and Dundee about the time of ‘Friday the 13th and Everything’s Rosie’. It wasn’t really picking up there yet, but Edinburgh and Glasgow was pretty solid and so was London funnily enough. We were up and down to London practically every week. We had a residency in the Mean Fiddler.

Then when ‘Friday the 13th’ came out it really turned things around up North. We played the Lemon Tree in Aberdeen just after that album came out and it sold out. That was a total shock actually because we didn’t think that it was going to have that much of an effect.

We really gigged a lot though. We played a lot of gigs to absolutely empty places. It just turned around through sheer persistence.

PB : You toured nationally on a co-headline tour with the Four of Us. Was that the only national tour that you did ?

GG : We did a few headline tours of our own as well of the toilets. We were probably stretching ourselves a bit when it came to outside Scotland . Middle England was just like a wasteland.

PB : How did you become involved with Silvertone ?

GG : As soon as the word started getting out about us, we began to get a lot of label interest from the majors. We got offered a deal from Chrysalis really quickly. We actually had a big long fax of a contract from them and then on the day it arrived and we were going to sign to them the whole of the department we were working with got fired.

Then there was Sony. I think our manager asked them for something like a million pounds (Laughs).Word about that got around and it discredited us and the credibility of working with us.

After that there was a gap. Silvertone was just another label which was floating around. They came to see us and then they kept coming back. It was quite a long courtship. It wasn’t an instant thing but even with them it was never written in the stars. One of the two A and R guys we had been working with, and who we had really hit it off, was fired on the day we signed to them. It wasn’t the greatest of introductions.

PB : Silvertone had also recently been involved in its infamous legal interaction with the Stone Roses. Was that something which worried you or did it not bother you at all ?

GG : No. We were completely clueless. Both the Halls had been to university and had done really, really well. They were really bright. Richard is very bright as well, but we were like a bunch of hicks when it came to deals. I was pretty fatalistic in the sense that I thought that whatever happened was going to be the right thing. I just went along with it at the time.

PB : You recorded ‘The Land of Do As You Please’ first. Was that an album that took a long time to record ?

GG : We decided to make it in Castle Sound Studios in Pencaitland in East Lothian and were given six weeks to make the album. That to me especially nowadays seems like an enormous time. Actually being given a slot where that is solidly what you are going be doing, a whole six weeks, that was a lot of time. I have never had that since. It certainly didn’t drag on though. We worked hard.

PB : ‘Friday the 13th’ first was recorded secondly, but released first as a means of raising publicity for the band before the 'The Land of Do As You Please', and the debut album proper, came out. Whose idea was that ?

GG : That was mine. Things weren’t going the way we wanted it to go with the record label. We were not sure if they were going to release ‘The Land of Do As You Please’ because they kept putting it on hold. At that time I was being really productive and doing a lot of writing. The album was recorded, but we weren’t really playing a lot of the songs from it live. We had already moved on.

I don’t know where I got the initiative for it from, but I wrote the record company a letter in which I laid everything out to them, saying, “Look. It won’t cost you anything to do this. It will be just a couple of grand and it will keep the interest and momentum there and build things up for the release of the album.” They just went along with it.

PB : In hindsight do you think that that was a good idea ?

GG : I think in hindsight we shouldn’t have released ‘The Land of Do As You Please’. We had already moved on to writing songs for our third album. The problem was we just superseded the first album. In a sense it was much more of an innocent album than the other two. ‘Friday the 13th’ was very much a live record. We had become very much a real road band by then.

The reactions for ‘Friday the 13th’ were just across the board. They were brilliant. There was a lot of respect for this up-and-coming, indie band, but the reaction towards ‘The Land of Do As You Please’ was very lukewarm and much more thin on the ground.

I think the songs win out on that one. Some of the songs like ‘You Can’t Win Them All Mum ’still stand up, but ‘Friday the 13th’ was much more of a spontaneous album. I think it captured the energy of the band much better. If you had been primed up into thinking that ‘Friday the 13th’ was the first album, then ‘The Land of Do As You Please’ would have come across as a lot more staid.

‘You Can’t Win Them All Mum’ was getting a lot of airplay especially in Scotland and it had got just to no. 72 in the charts . The label, however, dropped us just as it got there. If the label had stuck with us, it would have maybe been a different story and ‘The Land of Do As You Please’ would have maybe stood more of a chance.

Picture Gallery:-