Television

-

The Drug of the Nation : Part 1

published: 17 /

8 /

2003

In the first part of a definitive two part feature on the influential 70's group Television, which we are running concurrently this month, Jon Rogers examines their early years on the New York punk scene

Article

The Ramones may have had the gabba-gabba hey, Blondie might have had the pop sensibilities and the allure of singer Debbie Harry, and Patti Smith might have the fuck-you attitude of the New York new wave scene in the mid-seventies but Television had the guitars. And two of them at that.

Effectively, Television were at the forefront of what would become known as new wave. The urban scene attracted a mixture of outsider nightlife, renegades and art students that the prevailing musical taste of Kiss, the Eagles and Linda Ronstadt didn't cater for.

Along with a romantic sense of nihilism, urbanism and rebellion New York's new wave movement was also literate and well read. Early editions of the fanzine 'Punk' included Richard Hell on German philosopher Frederich Nietzsche, Television discussing the Bohemian poet and writer Gérard de Nerval and Patti Smith also aired her views on her hero and inspiration Arthur Rimbaud. Television guitarist and singer Tom Verlaine would also tell this writer later that he considered the Beat writer William S Burroughs "one of the genius writers of the literary world" and once had the pleasure of discussing dreams with the writer at a party. Verlaine though played down his literary knowledge in an interview with Dutch poet-journalist Hendrik Gelder saying that while he made "discoveries" such as Lorca, "the Frenchies" and Tomas Transtromer in the 70's he didn't think he was widely read. What inspired him was "their apparent command of the freedom of the verbal mind, the pleasure of writing oneself in and out of corners."

It was rock and roll with brains.

Antagonistic to punk's elevation of the inability to play as a virtue was Verlaine's skill and dexterity with six strings. "He was always an interesting and really good guitar player," vouched bassist Fred Smith to 'Musician' in 1992. "You could tell he's studied hard. He has a lot of musical knowledge. He can write a bridge in three seconds flat."

"There was something about it that was very vigorous," says punk film director Mary Harron in Jon Savage's book 'England's Dreaming'. "It had an art element to it, always. I liked that time of decay. There was nihilism in the atmosphere, a longing to die. Part of the feeling of New York at that time was this longing for oblivion, that you were about to disintegrate, go the way of this bankrupt, crumbling city. Yet there was something almost mystically wonderful."

Verlaine, though, wasn't totally convinced by the new wave tag. "We may be new wave," he debated with Dave Schulps of 'Trouser Press' in 1978. "We may not be punk, but we might be new wave in a sense. I guess there's something new about us. I don't know what it is though. Maybe it's that we don't use Les Pauls and Marshalls."

A prototype of Television was formed in the early 1970s when Verlaine (born Thomas Miller in December 1949) hooked up with bassist Richard Hell (born Richard Myers) and drummer Billy Ficca as the Neon Boys. "I thought we should start a band," Hell told Jon Savage later. "We saw ourselves as slum kids with big visions. I was trying to penetrate the conventions and the lies of mass culture and undermine this idea of 'rock star as idol'."

Verlaine and Hell had known each other since they had attended the same school in Wilmington, Delaware. "The school was like a glorified reform school really," recollected Hell. "Like a country club reform school. It was where middle-class people sent their kids they couldn't deal with. That's where we met."

The two of them would stay in touch when Hell moved to New York and Verlaine studied at college in Pennsylvania and while both had a keen interest in rock music they both had strong aspirations to become poets rather than musicians. "I had a history of interest in poetry," says Hell. "I was always a literary type. I was really influenced by the twisted French aestheticism of the late nineteenth century like Rimbaud, Verlaine, Huysmans, Baudelaire, etc. Moving up into the 20th century I also admired the surrealists Breton and Vallejo. And a lot of my view of the world came from that."

Strangely, for someone that now has a strong reputation as talented guitarist, Verlaine initially hated guitar music. It was the piano that first captured his musical interest. "When I was a kid," he told 'Guitar Player' in 1993. "I'd be really transported by symphonies. My mother would get these supermarket records of overtures or something, and that was music for me. The only thing I liked on the radio were flying saucer songs. In the early 60's I hated pop. I had a brother who bought Motown, and I thought it was totally twee."

Verlaine started playing the saxophone around 1963 after hearing a friend's John Coltrane, Albert Ayler, Eric Dolphy and Ornette Coleman records: "I got a sax for about $30. I used to have these jam sessions with a friend. We couldn't play at all; we just used to like to make noise. I was especially into saxophone players then, guys like Coltrane and Albert Ayler." Initially, Verlaine preferred the sounds of modern jazz but the first rock and roll songs to make any sort of impact on him were the Rolling Stones (particularly '19th Nervous Breakdown') and records by the Yardbirds, which also led him to the blues players.

Soon, though, the guitar began to usurp Verlaine's saxophone and he formed a very short-lived high school band with a local drummer, Billy Ficca. Verlaine though quickly became disenchanted with formal education and soon dropped out in November 1967, and, after messing around for nine months "taking drugs and growing up", he moved to where Hell already was - New York. Once there, the pair set about taking a load of hallucinogenics.

The first collaboration between the two would be poetic rather than musical: a book of poetry called 'Wanna Go Out?' It was universally ignored by the critics and everyone else. The failure to gain recognition in the literary world fuelled their desire to try to make an impact in the musical one. "I was 20 at the time and it felt futile" recollected Hell. "I wanted to shake up the world. I wanted to make noise, but nobody reads. I wanted to be true to my heroes, but I could see reading could be very boring and I got to feel that was a dead end. About 1972-73 we decided we were going to make a band. I was really inspired by the attitude of the New York Dolls and the Stooges."

Whilst Hell and Verlaine were listening to the likes of American garage bands in the late 60s, such as the Velvet Underground they also picked-up on the British groups such as the Beatles, Rolling Stones, Them and the Yardbirds.

The band that they formed, along with Ficca, was the Neon Boys. The exact chronology of that short-lived band has been lost but according to Clinton Heylin's book 'From the Velvets to the Voidoids' the band lasted from around autumn 1972 (although other biographies suggest 1971) to April 1973 and recorded a grand total of six songs - three sung by Hell ('That's All I Know Right Now', 'Love Comes in Spurts' and 'High-Heeled Wheels') and three sung by Verlaine ('Tramp', 'Hot Dog' and 'Poor Circulation').

One initial problem was that Hell really was a complete musical novice and had to be taught the bass parts for each song. As well, the band was always conceived as having twin-guitars and finding a second guitarist wasn't so easy. At the time Verlaine was putting together the band he approached guitarist Chris Stein (later to find fame in Blondie) to join but, according to Verlaine, he didn't like the songs they had. Another hopeful was Douglas Colvin but he couldn't meet even the rudimentary requirements needed. Later, Colvin would make his mark on the scene as Dee Dee Ramone.

So far only the three tracks where Hell sings have been released: 'That's All I Know Right Now' and 'Love Comes in Spurts' on the 1980 EP 'Richard Hell: Past and Present' with the CD re-release adding 'High-Heeled Wheels'. None were particularly accomplished; all teenagers filled with angst and frustration bashing away on trebly guitars but still managed to capture the band's vitality. For Hell, though, the Neon Boys marked the peak of his collaboration with Verlaine. "The way that the Neon Boys sound on [the released] cuts is the way Television sounded its best as far as I'm concerned. That's when we were on the same wavelength."

Although the band had laid down a rough and ready musical blueprint, perhaps more importantly Hell had created his visual image: shades, black leather jacket, ripped T-shirts and short, spiky hair. It was a style that mixed together the Beat Generation sense of existential freedom and the beautiful but tragic image of the poète maudit (as epitomised by the likes of the French poets Charles Baudelaire, Paul Verlaine and Arthur Rimbaud) as well as making an anti-glam statement It combined the classic elements of violence (and by association death) and sexuality. If anyone gave punk its sense of sartorial elegance it was Hell. "There were some artists that I admired who looked like that," said Hell. "Rimbaud looked like that. [Antonin] Artaud looked like that. And it also looked like the kid in [Francois] Truffaut's movie 'The 400 Blows'".

By the end of 1973, with the addition of rhythm guitarist Richard Lloyd, they'd turned themselves into Television. Lloyd, who was born in Pittsburgh and moved to New York when he was 8, had been introduced to Verlaine through a mutual friend, Terry Ork, who became their first manager (and had the album 'Marquee Moon' dedicated to him). Ork, an old friend of Andy Warhol, knew that Verlaine had been searching for a second guitarist and persuaded Lloyd to check-out the guitarist who was playing at the Reno Sweeny. "Verlaine played three songs, one of which was 'Venus de Milo'" recollected Lloyd to 'ZigZag' in November 1978. "The atmosphere and the actual playing he was doing prompted me to say to Terry, who subsequently told it to Richard Hell, that if someone got Tom and I together, the result would be one band that someone would like." A week later the pair were jamming together. Now that the band were now a four-piece it was decided that a change of name was necessary. After rejecting such monikers as Goo Goo and the Libertines, Hell suggested Television. According to Lloyd: "We wanted something that was really tinkly and mechanical, something that blared out. It's always there. It's so there that you lose your consciousness about it. 'Television' just seemed to fit that bill." The band's first gig was at the 88-seater Townhouse Theatre on 2 March 1974. "After we did that first gig," says Verlaine. "I remember thinking: We've got to rehearse a lot more. This sounds horrible." Rehearsing was just one problem, actually playing live was another as Mercers, the place for aspiring bands to play had crumbled to the ground in the previous August and there was nowhere else to go as Max's Kansas City was now only booking bands through the record companies with its glory days long gone.

The band seem to have secured themselves a Sunday night residency at the Bowery club and former Hell's Angel hang-out Country Blue Grass and Blues (CBGBs) owned by Hilly Kristal purely by chance. "Tom and I were walking down from his house to the loft in Chinatown [where Lloyd lived]" recounted Lloyd. "We passed this place which the owner was outside fixing up. We asked if maybe we could play there - and he told us he was going to call the place Country Blue Grass and Blues. So we said we play stuff like that. He gave us a gig, so we got a whole bunch of friends down and convinced him to give us every Sunday for a month."

The club, which had opened in December 1973 as the CBGBs would be a focal point for the emerging new wave bands coming along with Television like Blondie, the Ramones, Talking Heads, Patti Smith, the Dead Boys, Suicide and Wayne County would all play there. An early version of Blondie, the Stillettoes, would even support Television there in May.

The venue, though, wasn't the most salubrious of places. "CBGB's had a pool table in the middle" Lloyd recalled. "And a dog running around. And the dog would shit on the stage. They had a flophouse overhead, where bums could stay the night for 60 cents, and urine would leak down through the ceiling. And I remember wine dripping down on the microphone and sparking. And we'd be playing and the dog would come up and crap up against your leg and you'd be kicking it offstage. Very funny."

It was around this time that the band got what was probably their first write-up. Josh Feigenbaum in 'The Soho Weekly News' wrote: "The great thing about this band is they have absolutely no musical or socially redeeming characteristics and they know it." David Bowie, who saw one of the band's early shows was more positive: "The most original band I've seen in New York. They have it." Bowie would later cover Verlaine's 'Kingdom Come' on his 1980 album 'Scary Monsters and Super Creeps'.

By all accounts Television's early shows were ramshackle affairs. "The video of our first show " related Verlaine "reminded me of 'Anarchy in the UK'. We used to knock down all the mikes and lay on the floor and writhe in laughter while we were playing." Another video apparently has the band kicking each other and Hell knocks over a mike stand before falling to the floor himself - but still manages to keep on singing into it. Bob Quine, future guitarist with Richard Hell's group the Voidoids thought: "They were completely unprofessional. They were out of tune at all times. I didn't know what to make of them. The thing that surprised me most was how unprofessional they were." The Stillettoes singer Debbie Harry thought they were no better or worse than anyone else at the time: "As far as expertise went they were the same as the other bands, although they had a slightly different sound that was very droney. They weren't trying to be slick." The band did get a glowing write-up in the 'NME' from Charles Shaar Murray, who wrote: "Television are [sic] a total product of New York; they embody both the traditional and the revolutionary and they represent an imaginative return to basics." Island A&R man Richard Williams decided that they were "awfully rickety, almost amateurish" but still "there was something interesting happening, and most of it was vested in the gawky, angular, painted figure of Verlaine."

Tension between Hell and Verlaine was beginning to rear up although according to Hell: "Tom and I kind of hated each other from the beginning but there was some mutual ground which we didn't share with anyone else," he wrote later. According to Hell the conflict stemmed from Verlaine's resentment of Hell for causing the audience to be distracted from the music. "I wanted us to stand for something that showed in everything we did" argued Hell. "And that included clothes and the look of our graphics and all that imagery kind of thing. And that was part of the disagreement. Tom resented my preoccupation with this imagery stuff."

Despite, or perhaps because of, the tension both Hell and Verlaine were prolific songwriters, writing some 40 to 50 songs in this period, according to Lloyd. The most important to be written during this period in early 1975 was Hell's anthemic 'Blank Generation'. Designed as an antidote to the Who's 'My Generation' it was a slice of modern, urban teenage angst and defined Hell's persona in a fiery burst of guitars. "To me, blank is a line where you can fill in anything," explained Hell. "It's positive. It's the idea that you have the option of making yourself anything you want, filling in the blank. It's saying I entirely reject your standards for judging my behaviour." Along with 'Blank Generation' the writing partnership was coming up with songs like 'I Don't Care', 'Change Your Channels', 'Hard On Love', 'One on Top of Another' and 'Fuck Rock & Roll'. Unfortunately, any demo tape of these songs was lost long ago. The only song from this period to make it onto the debut album was 'Venus de Milo'.

One group Television did have a close affinity to was Patti Smith's band who had also also started hanging around the CBGBs in 1974 with her and guitarist Lenny Kaye also airing their views on the current New York scene in the pages of various magazines such as 'Creem', 'Rock Scene' and 'Hit Parader'. Along with Hell and Verlaine, Smith came from a poetry background and also had similar tastes in music. Hell had nearly printed a book of Smith's poetry before he'd been distracted by rock and roll. Smith and Verlaine struck up a close friendship and soon he was playing on her first single. The two would also, later, compose a couple of songs together and write a small pamphlet of poetry called 'The Night'. The mutual appreciation also extended to Smith writing a two page article in the October 1974 issue of 'Rock Scene'. To Smith, Verlaine "plays lead guitar with angular inverted passion like a thousand bluebirds screaming," while Hell was "straight outta desolation row doing the splits". For her, they were also "inspired enough below the belt to prove that SEX is not dead in rock and roll." The two groups were, in Lenny Kaye's words "becoming like a brother and sister band." They even shared two joint residencies, firstly at Max's in late August 1974 and then at the CBGBs in March 1975, slowly building up reviews and comments in magazines such as 'Creem' and 'The Village Voice'.

Conflict over the polar opposites in on-stage style between Verlaine and Hell was still increasing. "I have a completely different attitude towards performance than [Verlaine]. To me, it's just a total catharsis, physically and mentally. To them, it's just mental. It reached a point in Television where we had entirely different ends in mind. I used to go really wild on stage and the first thing that indicated I was on the way out was when he told me to stop moving on stage. He said he didn't want people to be distracted when he was singing. When that happened I knew it was over."

Another source of unease arose because Verlaine slowly started phasing out Hell's songs from the band's live set. By the beginning of 1975 Hell had been reduced to singing just two songs 'Love Comes in Spurts' and 'Blank Generation'. Little by little Verlaine chopped Hell's songs from their live gigs. Eventually, Verlaine even suggested dropping the popular 'Blank Generation'. Hell realised it was time to leave.

To compound the situation, after months of playing live Television had been offered the chance to record some of their songs for Island with Richard Williams and Brian Eno co-producing. Verlaine flatly refused to record any of Hell's songs. To Hell's mind, Television had effectively become the Tom Verlaine Band. "I was just there in form," according to Hell. "I was basically squeezed out. Verlaine was gradually depriving me of any role in the group and when it reached the point that it was just in tolerable I left. And I felt totally betrayed. We'd been best friends." Verlaine just wasn't enthusiastic about Hell's singing. "My whole orientation was towards music and performance" related Verlaine. "Rather than getting the photographs right." Also of concern to Verlaine was Hell's musical ability. "Richard didn't play very well, "stated Verlaine. "He was more or less learning how to play bass, it didn't matter for a while, then we'd hear a few tapes of the band and it would sound funny."

The band recorded five songs for the Island demo: 'Prove It', 'Venus de Milo', 'Marquee Moon', 'Double Exposure' and 'Friction' but Verlaine wasn't happy with the results. Not because of anyone's playing, more the production. "I didn't care for the sound he got on tape," he told Gelder. "Or the performance much either. The rest of the band felt the same way." On hearing the results Verlaine was convinced that the band wasn't ready to actually make a record - and Hell was on the point of quitting any way.

According to Verlaine, the tape was heard by Roxy Music via an A&R man at Island and that the band then lifted a number of ideas and lyrical phrases that would later appear on their 1975 album 'Siren'. "In one ear and out of his mouth," was Verlaine's comment on Bryan Ferry's alleged pilfering.

Verlaine's new direction for the group would also alienate Hell further. While Verlaine and Hell initially shared the same aesthetic of primitive, garage rock Verlaine was quickly outgrowing the form and looking to expand the group's sound. Hell, preferring a short, sharp blast of rudimentary energy didn't care for Verlaine's new direction. "Eventually, the band was progressing " recollected Lloyd "to the point that Richard didn't necessarily want to make the effort to get to. It got to be tedious because you'd be jamming and really going out someplace and you'd find you were being held back." Verlaine wanted to incorporate elements of his jazz roots along with elements of classic rock and roll from the 60's. "I got more into the improvisational stuff" said Verlaine. "It wasn't wanting to play longer songs. It was just being on stage and wanting to create something. That much comes from jazz or even the Doors or the 'Five Live Yardbirds' album."

Although Hell was yet to actually leave the group, Verlaine already had someone in mind to take over - Fred Smith, then bassist with Blondie. "I invited him [Smith] down one night to fool around," recollected Verlaine. "Because another friend of mine had been talking to him and he said how much he liked our material."

With the writing on the wall - in big, tall letters, Hell left in March 1975, playing his last gigs with the band at the "comeback" gigs of the New York Dolls at the Little Hippodrome. "When we got Fred it clicked immediately," related Verlaine. "At the first rehearsal me and Lloyd were looking at each other and thinking God, this is a real relief. It was like having lightning rod you could spark around. Something was there that wasn't there before."

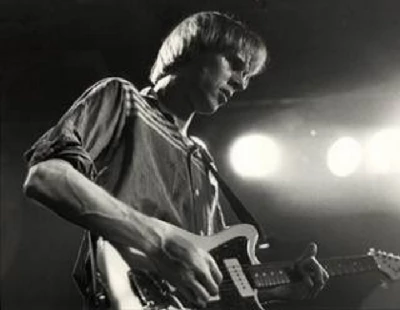

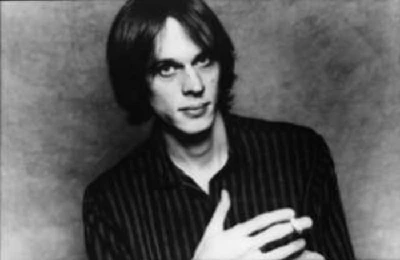

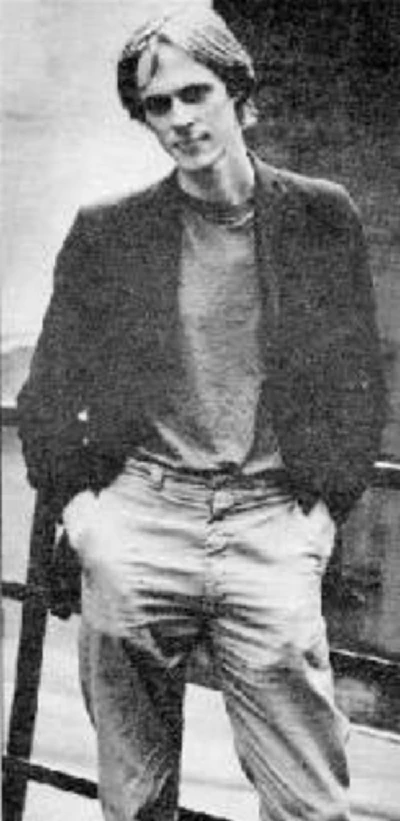

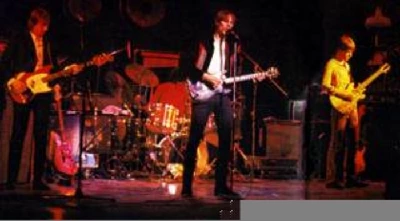

Picture Gallery:-