published: 26 /

5 /

2023

Guitarist, front man and songwriter Tommy James, with The Shondells, and as solo artist, is one of the greatest influencers of the 21st century. With Lisa Torem, James chronicles early times, principles of songwriting and news about his life story detailed in a film and musical.

Article

Tommy James is one of an elite handful of super-stars that catapulted to fame in the 1960s and continues to attract multi-generational fans. According to the liner notes of ‘Tommy James and The Shondells: 40 Years, The Complete Singles Collection (1966-2006)' ‘Hanky Panky’ became the biggest record of the summer of 1966,’ yet that landmark hit merely jumpstarted James’s extraordinary, decades-long career.

That recently-released album features bonus track, ‘Long Pony Tail,’ a nod to early years with Tom and the Tornadoes, where James’s voice mirrors the intensity of his personal inspiration, Elvis Presley, while the rest of the record underscores a host of beloved chart-toppers.

Over the years, James remained open to multiple musical influences, including R & B with Luther Vandross (Millenium Records, ‘Three Times in Love,’ 1979) and to jazz, with, among others, instrumentalist Michael Brecker.

This engaging singer-songwriter and guitarist, originally born Tommy Jackson in Dayton, Ohio but raised in Niles, Michigan, began his musical career at the age of twelve with The Echoes.

But he came to fame as front man, guitarist, and writer/co-writer with Tommy James and The Shondells. This upbeat pop/rock band was initially comprised of guitarist Eddie Gray, bassist Mike Vale, keyboardist Ron Rosman and drummer Pete Lucia. Their hits included: ‘Crimson and Clover,’ ‘Hanky Panky’ (solid gold single), ‘I Think We’re Alone Now,’ and ‘Mony Mony’.

Then, James established a successful solo career in 1970. He initially recorded a self-titled debut and the follow-up ‘Christian of the World.’ Hits included ‘Draggin’ The Line’ (with Bob King) and ‘Three Times in Love.’

More than 300 musical artists, including Billy Idol, Tiffany, Dolly Parton and Prince, have covered James’s rich, relatable material. And at the time of this writing, his songs continue to be sought after by talented industry acts.

In this interview with Pennyblackmusic, James discusses his rise to fame, his dubious relationship with Roulette Record Label executive Morris Levy, his perspectives on songwriting and the memoir that ultimately linked arms with Broadway, Hollywood movers and shakers and faithful fans from every walk of life.

PB: Hi Tommy. Can you circle back to the beginning of your career?

TJ: Sure. I had recorded ‘Hanky Panky’ in high school at the local radio station. I met both of the guys who owned these little labels, Northway Sound and Snap Records, when working at the Spin It record shop.

The second owner, DJ Jack Douglas, was from Snap Records. With Douglas, we recorded four songs: one was ‘Hanky Panky’ and two were put out as an A/B side earlier. Then, in early 1964, we released ‘Hanky Panky.’ Although it was on the radio locally, we didn’t have any distribution so the record just kind of died.

PB: And you were still relatively young when this all happened.

TJ: Yes. The following year, 1965, I graduated from high school. The guys I knew were playing weekends in a cover band. So, after I graduated, I took my band on the road. We worked clubs in the Midwest. In early ’66, I was playing this dumpy little club in Janesville, Wisconsin. Right in the middle of the two weeks, the guy’s club gets closed down, by the I.R.S., for not paying taxes.

So, we went home feeling like losers and back to Niles. But that’s how God works because as soon as I got home I got the call that changed my life. That’s when a distributor in Pittsburgh called me up; I just happened to be home at that moment, and. if I hadn’t been home, we never would have gotten the call and you and I wouldn’t be talking (laughs).

The distributor told me that ‘Hanky Panky’ had been bootlegged in the city of Pittsburgh. They had this little underground record operation going on there. The company bootlegged 80,000 records and sold them in ten days and we were sitting at number one in Pittsburgh.

Pittsburgh happened to be a major market so they asked if I could come--I couldn’t put the original band back together, but they asked me to talk to the TV and radio people. I agreed. Then, Jack Douglas and I drove to Pittsburgh. And sure enough, we’re number one.

PB: So, you hear the news that every artist wants to hear but there you were, without a band…

TJ: I grabbed a new group that was playing in clubs to become “the new” Shondells, grabbed a manager, and headed to New York to sell the master. We get to New York, and because it’s a regional breakout in the trade papers - Pittsburgh works a major market - we got a yes from everybody.

We got a yes from RCA. We got a yes from Columbia. Epic. Atlantic. Everybody. The last place we took a record to was a small, independent label called Roulette. So, since we got a yes from everybody, I went to bed thinking that we were going to be with one of the corporate labels, Columbia or RCA.

Woke up the next morning and, at about 10, all the other companies that had said yes, called up and said, “Listen, we’ve got to pass.” I said, “What the hell’s going on? We had a deal.’” Finally, Jerry Wexler, up at Atlantic Records, told me the truth, that Morris Levy, the head of Roulette Records, called all the other labels and backed them down. He’d said, “This is my record. Back off.” (James lowers his voice to imitate Morris Levy’s distinctive growl.) Jerry told me that the label was “all mobbed up.”

Morris scared them all. They all backed out and we were, apparently, going to be on Roulette Records. Sure enough, we signed. I met Morris Levy and it was like meeting a character right out of the movies. His weight was probably 250-260. He was just a real big, scary guy.

PB: The relationship would turn out to be, as you described in a recent concert, “a mixed bag.”

TJ: Yes. I signed contracts up there with Morris. Then, they put the record out and ‘Hanky Panky’ went to number one all over the world. If we had gone with one of those corporate labels, we would have been lucky to have been a one-hit wonder because the competition would have been so great and we would have been handed off to an in-house A & R producer, and that’s probably the last time anyone would have heard from us.

And Roulette actually needed us. They hadn’t had a hit in three years. And from a creative standpoint, it couldn’t have been a better place for us to be because I got to really learn my craft. I was in charge of the group and I was in charge of my own career. That would have never happened at another label.

At any rate, we had a great time at Roulette. We ended up with twenty-three gold singles and nine platinum albums. We did over 110 million records. From that standpoint, it was phenomenal. It wouldn’t have happened anywhere else, but, of course, getting paid was a whole other story. Getting paid was like taking a bone from a Doberman. That just wasn’t going to happen. Crime doesn’t pay, you know…

PB: At one point, you co-wrote with Bob King and recorded with Elvis sidemen Scotty Moore and DJ Fontana. What was it like working with these sidemen and collaborating with King?

TJ: This project took place in 1971 in Nashville for the recording of the album, ‘My Head, My Bed and My Red Guitar’. It was wonderful. The reason that I was in Nashville was that there was a gang war going on in New York. I was told that it wouldn’t be a bad idea if I left town until this thing ended because if they couldn’t get Morris—he was on the wrong side, by the way; the Gambinos were taking over New York and they figured if they couldn’t get Morris they would get whomever was making Morris money. My lawyer said, “Tommy, that’s you.”

My whole relationship with Roulette was tumultuous. It was crazy and scary because unbeknownst to me, when we signed with Roulette, the label was a cover for the Genovese crime family. So, while we were hanky panky-ing and mony mony-ing and all this other stuff, there was this very dark, sinister story going on behind us that we couldn’t talk about.

That always dogged us and we were always having to deal with that. My memoir, ‘Me, The Mob and The Music’ (co-written by Martin Fitzpatrick, 2010) was our whole relationship with Roulette. But in spite of it all, Morris Levy and I respected each other. It was a very strange relationship, like an abusive father and son relationship, but it was a very human relationship. Morris was probably the most fascinating character that I ever met.

But moving on, when I began a solo career after The Shondells, I did a lot of musical experimenting. Roulette represented Pete Drake and several other acts in Nashville. I went down and Drake and I, and Bob King produced this album in Nashville in 1971 with several of Elvis’s sideman, Scotty More and DJ Fontana. As a matter of fact, Scotty was the engineer. It was his studio. So, it was a real kick working in Nashville, especially with all of these famous pickers, as they call them. It was maybe the best album I’d ever done up until that point.

PB: You’re a prolific songwriter, having written in collaboration and on your own. What’s your preference?

TJ: I did a lot of writing with Ritchie Cordell, who was also one of my producers for several years. And I did a lot of writing with Mike Vale from the group. And with Pete Lucia Jr., we co-wrote ‘Crimson and Clover’ and several other tunes. I liked writing with other people more than I liked writing alone, bouncing ideas off of each other. But I write alone too sometimes. It’s not as much fun but I get the job done.

PB: Is there one factor that overrides the others? Do you start with a riff, a melodic line or chord changes, or is it a more random, unpredictable process?

TJ: Basically, it can come from anywhere. A lot of times, I’ll start with the rhythm, like a cheap drum machine. I’ll find a groove that I like. It’s funny, because when you write that way the song tends to tell you what the next move is. It tells you what it wants to become.

You start with the rhythm and you can pretty much tell by the rhythm what kind of song it’s going to be: a ballad, or a happy song, or something danceable. The groove, more than anything else, the rhythm pattern will tell you what the mood of the song is.

Then, the next thing that I want to write is the guitar chords. Usually, a melody will be in there; this is when I’m writing by myself.

And songwriters are always looking for titles. A title will usually tell you what a song wants to be. I like writing in stair steps like that. Sometimes a title will just stick out at you. It can come from a billboard. It can come from a matchbook cover, or somebody says something: a phrase or a sentence, and you’ll say, “Wow, that would make a great song title.” You’re always on the make for titles. It can come from anywhere. I wish there were a pattern to it. But when I write by myself, I tend to start with the groove.

Bo Gentry and Ritchie Cordell came to me with ‘I Think We’re Alone Now’ in 1966. They played me this thing on the piano and I knew, as soon as I heard the chorus, and as soon as I heard the hook, that this could be a big record. It was a hit. It was like a mid-tempo ballad. And we went into the studio to do a demo and I played guitar on it and that’s when I came up with (TJ imitates the song’s distinctive percussive sound) the throbbing eighth notes. It just kind of took on a whole new life. It was sped up and the eighth notes became sort of the signature sound of the record which changed the whole complexion of the song. We did the demo like that, took it back to Roulette and Morris went nuts for it.

PB: You were under pressure to create a title for America’s favorite party song, ‘Mony Mony.’ How did you resolve that problem?

TJ: ‘Mony Mony’ was sort of an accident. I just wanted to do a throwback record. This was 1968 by this time. I used to love what they called ‘party rock,’: Gary U.S. Bonds, Mitch Ryder, and guys like that put these classic party rock songs together. I always loved that, but by 1968 everybody was too stoned to party much.

Basically, we just started putting these tracks together. We were at Brooks Arthur’s studio. He was rather famous. Pete was on drums. I was playing guitar. A friend of ours was playing bass. We were just doing a demo. We caught on to something. We caught the right tempo. And we had no idea that we were working on a hit record. We just sort of built the thing, two to three instruments at a time. We came up with a chord pattern that we liked and that was the beginning of ‘Mony Mony.’ We worked on it several weeks like that. We did a lot of editing and gradually came up with the part, “I love you, Mony, Mony…” which was a separate part, and basically we had all of the words to the song except for the title.

We just had a bunch of silly lyrics, Ritchie and I, and we’re up at my apartment. It’s the night before we’re supposed to do the lead vocal and we still had no title. And we’re looking for one of those silly girl names: Sloopy or Bony Moronie, or something. Everything sounded so dumb. We threw our guitars down—this is in midtown Manhattan. We got out on my terrace and the first thing our eyes fall on was the Mutual of New York building. M.O.N.Y. with the dollar sign in the middle of the o. It would give you the time and the weather. We just started laughing because it hit us both at the same time. That was the perfect name for the song.

I’ve often thought, if we’d been looking in the other direction, that thing might have been called Hotel Taft, or Equitable (laughs). That was the perfect name and it became the title of the track.

PB: Creating a video of ‘Mony Mony’ was a real example of forward thinking. You would also conceptualize videos for ‘She’ and ‘Crystal Blue Persuasion.’

TJ: It made all the sense in the world to me to do a film of our hit record except we couldn’t get any TV stations in America to play it. The only place we could get the ‘Mony Mony’ video to be played was in Europe in between double-features, in which case, they’d play a cartoon or videos sometimes. That was the only place that we could get our music played. Eventually it ended up on what was called ‘The Beat Club’ in the UK because ‘Mony’ went to number one in England and it was one of the biggest records of the Sixties over there. In fact, it was bigger in England than it was here. It only went to number two in the States.

We were supposed to do ‘The Beat Club’ in the Sixties but we got called out because American vice-president Hubert Humphrey was running for president. He asked us if we would play at his rallies. (Humphrey would eventually ask James to become a youth liaison on the campaign trail). We said yes. We had to cancel our little tour in England and appearance on ‘The Beat Club’.

And the BBC went nuts, and basically never played another one of my records. The bottom line, though, was that ‘Mony Mony’ ended up at number one on ‘The Beat Club’. Then, in the early 1980s, it got shipped back here and it got played on VH1 and on MTV. The video eventually caught up with us. But we did it in 1968, and MTV didn’t come along until 1981. And they wouldn’t play the song on American television either.

PB: There were three versions of ‘Crimson and Clover.’ How did it originate?

TJ: ‘Crimson and Clover’ started out as a title. I dreamed it one night. I woke up in the morning with this title in my head. It sounded profound. it was two of my favorite words put together. It ended up being the most important record that we ever put together because it changed the course of our career and it really gave me the second half of the career.

We were working on ‘Crimson and Clover’ all during the presidential campaign of 1968 when I was out with Hubert Humphrey. So much was happening in 1968. FM radio started playing rock ‘n’ roll They had never played rock ‘n’ roll up until that point—it had been all jazz and classical. It really raised the bar on the sound of your records. First of all, they were in stereo. It wasn’t mono AM pop singles anymore. FM brought a whole new thing into it.

We left on the Humphrey campaign in August. The biggest artists on the radio were The Rascals, The Association, Gary Puckett, and I’m leaving a lot of people out, but they were all singles. When we got back ninety days later, it was all albums.

Suddenly, within that ninety-day period, the whole industry got turned upside down because of AM radio and the big multi-track tape recorders. We went from four-track to twenty-four track overnight.

There was a lot more to making records than there had been ninety-days ago. Basically, when we cut that, there was Led Zeppelin, Crosby Stills & Nash, Joe Cocker, Neil Young—all albums. There was this mass extinction of singles acts at that moment. It was all album people after that.

Only a few acts got to make that transition: Sly and the Family Stone and us because of ‘Crimson and Clover’, There was no other record that we’d ever made that had allowed us that transition from AM Top 40 pop singles to FM album-oriented progressive rock. There’s no other record we ever put out that would have done that in one shot like that. ‘Crimson and Clover’ did that for us. Roulette was never really selling records like Columbia and Reprieve and Atlantic. And suddenly we’re selling albums and that was a great responsibility.

So, it’s just by the grace of God that ‘Crimson and Clover’ ended up being our biggest record sales wise. We did about five and a half million singles in about six weeks. It was a phenomenal number of record sales. It went number one all over and then, Hubert Humphrey writes the liner notes to the ‘Crimson and Clover’ album.

PB: Your music has been widely covered. ‘Crimson and Clover,’ alone, has been covered by, among others, Dolly Parton and Prince in the 2000s. Looking back earlier, ‘Sugar on Sunday,’ was reimagined by The Clique in the 1960s; ‘Hanky Panky’ by The Cramps in the 1980s; ‘Draggin’ The Line’ by R.E.M. in the 1990s for the soundtrack of ‘Austin Powers: The Spy Who Shagged Me’. How do you account for the versatility and timelessness of your music?

TJ: Well, I just think that there’s great energy around the music. I feel that way about The Beach Boys and The Beatles and The Four Seasons; just good energy around the music because they were basically simple songs. They could be done in any number of ways. Dolly turned ‘Crimson and Clover’ into a country record. It was amazing. I play it on my radio show, ‘Gettin’ Together with Tommy James’ on Sirius/XM from time to time. She and I did a duet.

Of course, Tiffany (‘I Think We’re Alone Now’) and Billy Idol (‘Mony Mony’) and then The Boston Pops doing ‘Mony Mony’ (laughs). It’s hard to believe. I’m very grateful. I’m always very honoured and flattered when somebody does a cover of our songs.

Sony is my publisher. I was up there this week and they told me about this new record by The Shacks that’s the number one stream on TikTok. They’re covering ‘Crimson and Clover.’ And Billie Joe Armstrong from Green Day did a great version of ‘I Think We’re Alone Now,’ which came out last year and went top ten. So, we’ve been very, very lucky and I’m very flattered when somebody does one of our old songs. We’ve had over three hundred cover versions of our stuff.

PB: You’ve changed your style considerably over the course of your career. During the Fantasy Records era in Berkley, California, the Tower of Power horn sections yielded a ‘hard pop’ sound with ‘In Touch’ in the mid-1970s. In 1977, you recorded ‘Midnight Rider’ with ‘Hanky Panky’ writer Jeff Barry. You ushered in a softer sound, when collaborating with Michael McDonald (Doobie Brothers, etc.). Has switching gears been satisfying? Challenging?

TJ: I’ve been so lucky. First of all, the fans have always been with us as we’ve made these changes. I never thought in a million years in 1966 that we would still be doing ‘Hanky Panky’ in 2023. Not a chance in the world.

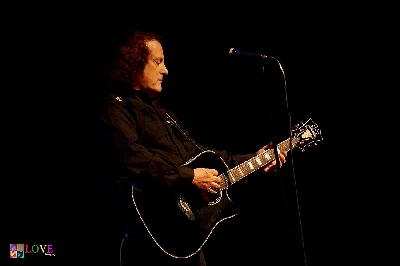

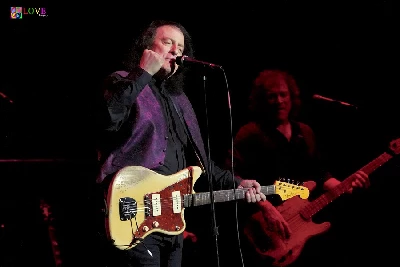

I look out at that concert crowd now and it gets bigger than ever. I see three generations of people. It’s absolutely phenomenal. So, I really relish being able to do rock ‘n’ roll this long. I’m 75 and I’m still doing what I was doing when I was fourteen. That’s like being a 75-year-old paper boy. I thank the good Lord and the fans for that kind of longevity that we’ve had and I really mean that.

PB: The future brings exciting news. Plans are in the works to create a screenplay and musical based on your memoir. To what extent will you be involved in the process?

TJ: I’m going to be co-producing. Barbara De Fina is actually the producer of the film. She produced ‘Goodfellas’ (1990), ‘Casino’ (1995) and ‘Hugo’ (2011). The screenplay has been written by Matthew Stone, an incredible screenwriter. Kathleen Marshall is directing. We have really an all-star team and I’m so thankful for that.

Hollywood was shut down for two-and-a half years because of Covid. They’re sort of up and running again and things are starting to move. So, they’re in the casting phrase right now. That’s going to be fun. But it’s going to be so much fun watching this all come together.

The two main characters, of course, are myself and Morris Levy. I’m amazed at how many of the young actors that might be playing me started out in rock bands. It’s incredible.

And of course, Jamie Fox really raised the bar when he did the movie, ‘Ray’ because he sang his own songs. And he sounded like Ray Charles. You can’t lip synch anymore. Whoever does it will actually have to play the music. These casting directors are so hip. They know everybody. They know who is available.

But the Morris Levy character is the one who is really important because he is the one that we were all involved around. So, his character and his persona and the actor who ends up portraying him will be really important.

PB: Casting sounds exciting. What other aspects of film production do you see yourself being involved in or observing closely?

TJ: Imagine putting the technical crew together! Everybody has to be available at the same moment. It’s great watching this all come together, but the other thing that I have to be careful of is that there’s a lot of shots in the studio. I have to be careful that the equipment is the equipment of that moment. I can’t have something from the 1990s in the studio when it’s supposed to be 1967. There are all kinds of geeks out there that are going to pick right up on it.

PB: So true. Between the DAT machines, boom boxes…tell us about your stint as a radio host.

TJ: We’re in our sixth year now with ‘Gettin’ Together with Tommy James’. When Sirius XM first came to me with the proposal, I was kind of scared because I had never worked that side of the mic before. I had never interviewed anybody. I’d never been a disc jockey (Laughs). It was three hours a week and that’s a lot of time to fill up.

But, as soon as I started doing the show, I began to love it. And during Covid, it was an excellent way to stay in touch with the fans because there were no concerts. It ended up being extremely important in my career because in-between the hits we end up playing a lot of rarities and songs that should have been hits, but weren’t.

PB: You’ve been touring since you were a young man. How do you feel about touring currently as opposed to the leaner years? Have you made a lot of changes?

TJ: I don’t like to go out for long durations of time because they’d find me in the hospital or under a trestle somewhere. I don’t know how these guys go up for six months at a time. I’d be a basket case in about a week, especially with our show.

I’ll work one day a week during concert season, which is basically March through October. I don’t like doing it anymore than that because I want to save my voice so it will be one-hundred percent every time we work. I want to keep it fresh.

We start in March and I’m working every weekend, either Friday or Saturday. I also keep my sanity that way. I also have to write the radio show and record it. So, that’s a lot of work. I’m also in the studio and writing, so I don’t have time to work anymore than that.

The show is basically an hour-and-a half. It’s the hits and I’m going to be putting in a new version of ‘I Think We’re Alone Now’. We had it out two years ago and it went to Top Twenty for us. It had been the first time in the charts in a long time, went to Top Twenty on the adult contemporary and so did the live album that it came from.

But it’s going to be the closing credits in the movie. It’s a slow, beautiful version of ‘I Think We’re Alone Now’. Morris Levy dies at the end of the show and it completely changes the meaning of the song from being a teen top record in 1967 to being a sombre moment because we’re alone when Morris dies. So, we’ll do that in the show.

But basically we have to play as many hits as we can cram into an hour-and-a half. There’s a lot of stuff we don’t play. We could play for four hours if we wanted to…

PB: I don’t doubt that. What advice in this rapidly changing industry can you give to young hopefuls?

TJ: I get asked that a lot. I really have an answer and I don’t want to make it too technical. I believe that the fastest way to become successful now, because it’s so hard to get noticed, and you can set your hair on fire and nobody cares.

I believe, that the fastest way to make it, is for the group to write their own songs, put about a dozen of them together, and don’t go to a record company—go to a publisher: Sony, EMI, Chapel Music. There are so many great publishers.

And go in business, basically, with your songs. If they like your music, they can make more stuff happen for you than anybody else. Record companies aren’t signing much of anybody today. Every now and then, something will walk through the door that’s a goldmine but not very often. It’s very hard getting a record deal and getting a record company to invest money in you, and time and effort, and a publisher will take you to a record company and you’ll have the clout behind you that you need to get in the door.

So, I would recommend going to a publisher before I’d go to a record company. Because you’d give the publisher either half or all of the publishing on the song which is ownership. You want to maintain your writing but you don’t need to maintain the publishing. Let a publisher who really knows what they’re doing publish your songs. They’ll get you in movies, commercials, TV.

PB: If you could repeat one day of your life…

TJ: Maybe the day I met my wife. That was magic.

PB: Thank you.

Band Links:-

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tommy_Ja

https://www.tommyjames.com/

https://www.facebook.com/TJandtheShond

https://twitter.com/TJShondellls

Play in YouTube:-

Picture Gallery:-

Visitor Comments:-

|

|

4286 Posted By: Bill Regan, Chicago area, USA on 15 May 2023 |

Just saw him tonight---in little old Des Plaines, Il movie theater, redone to handle concerts---1,000 people, like he said, 3 Generations of people. All rocking, all knowing every single word and beat to his songs. Guy is the showman--walked through the front part of the crowd during an extended MONY MONY play---shook hands, posed for pictures, I even got to shake his hand and say "I read your book"..he smiled and said "thank you"---the guy is incredible, his band tight, loud, and together. Dont miss the chance to see him Live. You know his music is a part of your Life's soundtrak no matter your age. The movie will be dynamite---quite the real story of the Him, The Mob and the Music.

|