published: 25 /

8 /

2015

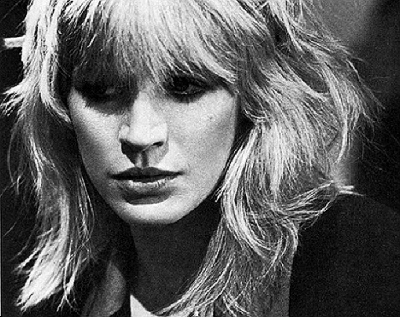

In this archival interview from March 1995, Nick Dent-Robinson speaks to Marianne Faithfull and late father Glyn about 'Faithfull', her then new autobiography

Article

Marianne Faithfull is making up for lost time. Following the success of her autobiography last year, she has the paperback to look forward to and a new album on the way. But most important of all, in her late 40s, she has found her father.

Marianne Faithfull largely lost touch with her father when she was six. Her mother spirited her away from the marital home and discouraged further contact. Marianne saw him on occasion over the years, but so infrequently that he was a stranger to her. And that, she feels, has been at the root of many of her considerable problems.

Marianne is wearing spray-on jeans and what she describes as tart’s boots, from which she sways somewhat precariously as she strides across the foyer of the Heathrow Hotel where we meet. She has come fresh from the “fantastical folly” she rents on an Irish estate. She lives almost as a recluse for most of each year save for an occasional foray into the limelight to promote either a book or, on this occasion, her new album, 'A Secret Life', available soon from Island Records.

Her voice is deep and wheezy, the result of constant smoking – with an actressy delivery. Immediately on sitting down, she orders wine and constantly waves the glass around throughout our conversation. She laughs like a gurgling drain. At almost 48 she sees herself as resurgent with the new album following on from last autumn’s publication of her autobiography which will be going into paperback in June. It was while she was completing the relentless publicity process for the hardback that she was quietly building new bridges with her father. Marianne has spent 40-odd years regarding him as a benevolent figure on the fringes of her life, essentially unconnected to her. But she sent the book to him and that has altered everything.

“I’m sure he didn’t know how hard my life has been and, obviously, reading the book, he has thought,‘Oh my God, better do something about this; I’m an old man.’ He wrote me the most wonderful letter I have ever had in my life. ‘Dearest Marianne, I’ve read your book … you are the product of a very strange wartime relationship, but that’s how it was. I’m so proud of you and so delighted you’ve become such a nice woman. From your dear old dad.’” She is framing it.

Glyn Faithfull is an octogenarian, frail but completely compos mentis. He lives in semi-retirement at the wonderful, wacky educational establishment he co-founded – Brazier’s Park in rural Oxfordshire. Here students come together to learn about the “group mind”.

He came up from the country for the London launch party for Marianne’s book, wearing his country suit, tweedy hat and Jesus sandals and socks, rubbing shoulders in a fashionable club with guests such as Anita Pallenberg, Van Morrison, Bill Wyman, Boy George, Damien Hirst and Bob Geldof. But Marianne does not mind sartorial gawkiness in anyone, let alone her lately discovered father. In décolleté and borrowed diamonds she was jubilant.

Glyn’s attendance was a public endorsement of their new intimacy: Is this for himself because he has waited so long to play dad? Or is it for her, I wonder? Marianne says, “That’s just a good man who is trying to help his little girl. He is turning into a saint, a truly accepting, compassionate being. My father is becoming much clearer to me now, which is crucial, it is going to change everything for me with men. He is clearing my path so that if I do want to fall in love again I will be able to. He sees that and is doing it quite consciously.”

Marianne has always displayed a knack for picking Mr Wrong. Mick Jagger, for example. According to her, he was a misogynist with bisexual tendencies: not a good candidate for high romance; not even a good sexual performer, she insists. There’s a skin-crawling scene in her book: Jagger making love to her while loudly fantasising about Keith Richards, who was within earshot, on the other side of a flimsy wall. Why on earth did she endure such humiliation? “I must have found it attractive,” she wails. “I was frightened of real men. I didn’t know much about them, still don't.” It all comes back to Daddy. “My father is a real man,” she adds, “But I didn’t know him. He was mysterious to me.”

As a very young child, Marianne had recurring nightmares about both her parents. One bad dream featured her late mother, Eva, roasting her in a pit. In another, malevolent creatures who looked just like her father scolded her. She remembers listening to her parents arguing over whether to leave a light on for her at night. She thought their rows were her fault. “I think, as childhoods go, mine was very frightening, but I can only say it was like training, from both of them, and without it I wouldn’t be me, and I wouldn’t have been able to do what I did.”

What does she mean by this? By anyone’s standards, her life is more famous for its waste of talents than its accomplishments. But she is completely without irony – and, to her great credit, completely without self-pity. She says, quite matter of factly: “They were both very selfish, my parents, they really were. And I was a very sensitive child. But I don’t think my parents and their generation knew how intense these things could be and how it affected you forever.”

Marianne was never going to be “conventional suburban”. Eva’s family were Austrian aristocrats on the slide. During the war, Eva was gang-raped by invading Russian soldiers. She married Major Glyn Faithfull in order to escape occupied Vienna, and once in England separated from him at the earliest opportunity. Thereafter she attempted, in their bleak and modest Reading terraced home, to turn Marianne into her own creature.

Marianne was only eight or nine when her mother told her the intimate details of her earlier life – the rape, the voracity (in her opinion) of her husband’s sexual appetite. Not your usual maternal chit chat. “I’m pretty sure I was her only companion for quite a while. She had to talk. I adored my mother. I remember thinking, ‘One day I will grow up and set all this right’ - I thought that a lot.” Marianne wheezes with laughter. “I didn’t realise I had given her more pain. Eva was very naughty. She did a lot of damage between my father and me. Even in my 40s, if I would go to see him, she would say, ‘Oh, you are going to see your father,’” she mimics a contemptuous mid-European drawl. “I always felt bad about just visiting him, let alone having a relationship with him. Eva couldn’t handle it. With her, it was all or nothing: if you love me, you won’t love him; if you love him, you can’t love me, and that’s that. She didn’t like men at all. It was very understandable. She had had a difficult life.”

As an eccentric himself, part of Glyn Faithfull relished Eva’s theatricality. Talking at his Brazier’s Park home, shortly after I had seen Marianne, he described Eva to me as a “very original, special character”. He seems to have encouraged Marianne’s childhood caprices. One of his fondest memories concerns a visit by a phalanx of aunts when Marianne, aged 7 or 8, appeared, stark naked, declaring, 'Look, everyone, I’m barefoot.' “She was always one for understatement,” he chuckles.

Glyn obviously has regrets about his role, or lack of it, in Marianne’s upbringing. On the one hand, like Marianne, he can be wilfully obtuse, coming out with barefaced claims like: “She has not suffered from the problems she had growing up.” On the other, he eventually says, with palpable sadness, “She was my first child. You make mistakes. You always make mistakes with the first one.” But it is clear that he feels that most of the mistakes fell to Eva rather than to him. He tells of Eva absconding when Marianne was very young. “She took Marianne to live with someone else, a new man she had discovered. But when he wouldn’t get divorced, Eva sent an SOS to me and I went to fetch them both back.”

He likes to think that Marianne remembers him “doing the right thing when required”. Actually, I rather suspect she doesn’t. Glyn is a shadowy character in her book, who disappears completely a third of the way through. Her perspectives on Eva are markedly different from Glyn's, too. Marianne sees the decision to send her to a convent school – neither parent was a practising Catholic – as a further maternal whim. Glyn sees it as nothing less than another malevolent manoeuvre in his war with his former wife. “No doubt she was sent there in order that I wouldn’t see her so often,” he says, bitterly. “You see, I am C of E originally and the Mother Superior was very much against me. The woman was one of those crazed Catholic zealots and I wasn’t allowed much access to Marianne at all.”

Eva was relentless. Having driven off Glyn, she decided Marianne was too solitary and needed a male figure in her life, so she muscled in on someone else’s son, Chris O’Dell, whose mother was dead, and whose father was ill. Eva had him come and live with them. And when they grew up and Marianne grew wild, Chris’s role was further defined. “Eva made him my official caretaker and he simply didn’t want the job,” Marianne wheezes. Eventually, Chris cut off all contact with them. Marianne herself came to realise that she, too, must leave the maternal home. “Eva was going to consume me. She was not just a smother mother, she was becoming power-crazy. My leaving broke her heart, but I couldn’t help it. A legacy of my convent school days, though, is that I still feel so much guilt about it.”

She seems to see traces of Eva’s possessiveness in herself. She has chosen to live in Ireland, “because I don’t want to impose on people, I don’t want to eat them up, I don’t want to do to them what was done to me”. For people, read her son, Nicholas, now thirty, by her first husband, John Dunbar, and her grandson, Oscar, one.

Marianne, of course, escaped Eva by means of a short interlude as a pop singer and married woman. Then, bored with all of that, she settled on being Mick Jagger’s girlfriend. “I wasn’t cut out for that kept-woman role then. Although I must say now I wouldn’t mind it one bit. Though not with Mick!”, she hoots, “But with someone else. I’m not so young now. I’m not so proud, I’m not so adamant about everything. I could handle it,” she trumpets. “However, I seem to have driven them all away.”

Marianne was at the heart of the Sixties. However, when you read her book, her life doesn’t sound exciting, but dreary and provincial. She saw the same people, week in, week out; they took drugs to alleviate the tedium – not so different from the bored teenagers in thousands of semi-detached bedrooms. But Marianne took more expensive and harder drugs.

She was immoderately promiscuous, and had a number of gay affairs also. She briefly wondered if she were, in fact, lesbian, but concluded she was not. As her least troublesome relationships seem to have been with women, how can she be so certain? “I just knew. I think those days were so very sexual because we were all doing so many drugs. Maybe it was a form of grand narcissism. We all felt we were so gorgeous and – for a real gay woman, this would be awful – a lot of that stuff is just like looking at your own reflection. My women friends (today) are more precious than anything but they are certainly not sexual. I sort of wish I were gay: I’d have a much nicer time, I’d have sex on a regular basis, I wouldn’t be so very lonely.”

She has forgotten many of her worst excesses: “It’s got nothing to do with drugs but with survival. A lot of the things I included in my book I would never have remembered if I hadn’t had to make myself. But now I am experiencing nightmares. Always nightmares. Because obviously when you start to think about the past, things come back that you didn’t want to recall.”

She has forgotten the details of the abortion she had when she was just 17, a schoolgirl pop singer on tour. Abortion was still illegal in 1964, so she suspects it must have been a grisly back street operation. Subsequent guilt was harder to disremember. When she later had Nicholas it seemed like absolution. “I have to say to you, I had more abortions. I didn’t go into them all in the book because it is such a touchy question, but over the years … I can’t even remember them all … I think I must have had two or three more, and I’m glad I did because those babies would all have been born addicted. I would never have wanted that.”

In the end, Marianne felt degraded, not least because of what she describes as Jagger’s misogyny. “You hate yourself. But I didn’t know it. If you had fired out a 21-gun salute at the time and said, ‘What’s going on with you?’, I couldn’t have told you. But I don’t blame Mick. At one point I did, actually, but I got over it. He was young and I was silly. Mind you, I don’t know how any other woman can live with him because I don’t expect he’s changed that much. He is still a woman-hater and very bisexual. It does make you think about what someone I otherwise admire like Jerry Hall could ever see in him; perhaps she is bisexual too? Who knows? I do wonder if Jerry will ever stay the long-term course with Mick. Anyway, back in the Sixties a million other men were doing just the same as Mick did. And so they are, still, I’m sure.”

She left Jagger and ended up a heroin addict living rough. She married and divorced twice more. Actually, her son Nicholas was the real love of her life, but John Dunbar fought her for custody and won. Eva tried to commit suicide when that happened. “It was terrible. She blamed me, you see,” says Marianne. “It was like her own life was ended. She lost me and then she lost Nicholas; she didn’t want to live any more. And I can’t really blame her.”

“Nicholas! – that little one. He wasn’t like me. They never are, are they? When he was born Eva tried desperately not to fall in love with him, because she didn’t want to go through this closeness thing with another child like she did with me. But, of course, she was lost, she put her whole heart into him, which is what she did with everything, always. And then he was taken away. None of us has ever got over it, really, not even Nicholas. I always thought maybe they did the right thing, but now I think that having Nicholas with me through those difficult years might have helped me. Perhaps it wouldn’t have helped him? But people have to do what they have to do. Anyway, it broke my mother’s heart.”

The two women were eerily alike. For example, both were prone to anorexia. “I was obviously trying to make myself disappear. I went down to seven stone (98 pounds), eating next to nothing. My anorexia was connected with addiction. Drugs precipitated a whole lot of horrors which were there; all I needed was to let them out. Eva had gone through the war years where they had very little to eat, and God knows what that does to you. Anorexia’s a very odd business, something we definitely had together, to do with not wanting to take up space, obliterating yourself, and not wanting men to notice you.”

During the worst period of her heroin addition, Marianne scarcely saw her father. He recalls only one meeting, when she was trying – unsuccessfully – to clean up at the Bexley Hospital. “She was being brave and doing what was needed.” His voice breaks as he says this to me.

In 1985, Chris Blackwell, founder of Island Records, shipped Marianne off to the American detox clinic, Hezleden. “I can’t say I’m really cured, I don’t think that is possible. But the desire to destroy myself daily is really gone,” she says.

She settled in Boston for a while and found herself a psychiatrist. “About 1987, I rang Eva and asked her to come out, and she did, with great trepidation, but she was valiant. She had a heart condition by then and wasn’t at all hip to the late 20th century.

“The first thing that struck her was how together I was; that I had actually learned some practical things, like buying more than one toilet roll at a time. She’d always thought I was completely hopeless. That was one of our problems. I took her to see Dr Bergman, my psychiatrist. My father had been a Psychiatric Professor at Oxford and so Eva knew enough about Freud to be terrified that she was to be made the evil witch. But I never thought like that. In fact those weeks in America were lovely, how our real life should always have been. I miss her so much now she’s gone. Eva and I had a very basic, central, physical relationship. The thing I miss more than anything really is the way she smelled. I used to love coming home and going to kiss her and just taking in her wonderful, exotic scent. And it was mother. And there isn’t anything like that.”

Eva died in 1990. She’s buried in a country churchyard at Aldworth, just ten miles from Glyn Faithfull’s home at Brazier’s Park. Glyn says that he always felt he had to cope with the difficult domestic situation by managing to keep his own feelings, particularly his anger towards Eva, unexpressed. “And I hope the fact that Marianne forgave Eva is some credit to me,” he says now.

Father and daughter see each other quite regularly these days,and she is reasonably close to his three children by his second marriage. One of her step-brothers is a budding artist, recently taking prizes in Fine Art at Reading University. Marianne encourages him by buying some of his sculptures which are often exhibited at art shows at Brazier’s Park. “Marianne is very giving, very kind. She has been good to my other children,” says Glyn. “I think I understand her better since reading the book,” he continues.

One might be forgiven for thinking that her book would have been a harrowing read for Glyn Faithfull, particularly at this late time in his life, but he says staunchly that it wasn’t. “It is a very revealing book. That she took the trouble to tell the truth, to discuss it with me – well, most fathers don’t get the luck of their children ever being so truthful. She is a jolly good daughter. I really appreciate her now.”

He feels, he says, that after all these years they have finally reached “untroubled waters”. It seems the Faithfull daughter has come home at last.

Band Links:-

http://www.mariannefaithfull.org.uk/

https://www.facebook.com/mariannefaith

https://x.com/faithfull_m

https://www.instagram.com/mariannefait

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Marianne

Picture Gallery:-

Visitor Comments:-

|

|

18647 Posted By: Ernestwax, Dominican Republic on 14 Aug 2025 edit

|

Thank you - your comment will be published once it has been reviewed

|