published: 3 /

4 /

2014

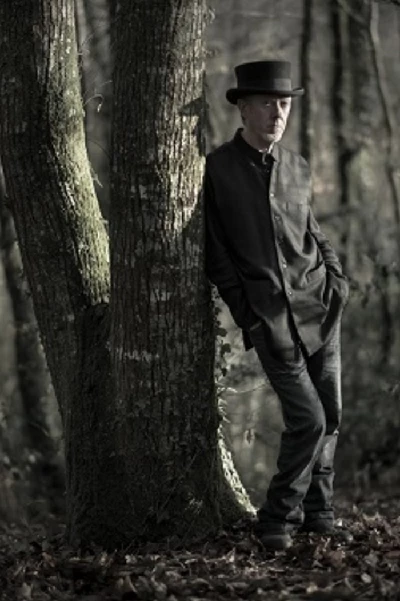

Phil Parfitt, the front man with underrated late 80's indie act the Perfect Disaster, speaks to Denzil Watson about his former band and 'Phil Parfitt and Friends', his new album and first release in twenty years

Article

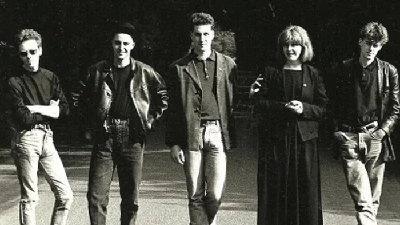

You may or may not be familiar with Phil Parfitt. He first became known to me in the late 80s when, back then, he fronted Velvet Underground-influenced alt-rockers The Perfect Disaster. In 1989 my band were due to support them at the now demolished Take Two Club in Attercliffe, Sheffield. Inquisitive, I purchased their then current album ‘Up’ and immediately made a connection with the band. In the end the gig got moved and we couldn’t support them on the new date. Ironically though my friend’s band ended up filling the support slot, so I ventured down to the venue and was duly blown away by their performance. I always remember the band lining up at the venue’s exit to shake the hand of every audience member as they filed out. I caught the band again later that year when they supported the Jesus and Mary Chain on their ‘Automatic’ Tour. By then, my love for them was cemented, so much so that Parfitt remains the one and only person I’ve ever written fan-male to, such was my admiration of his song-writing prowess.

After the demise of the band, Phil went on to form Oedipussy. Their sole album ‘Divan’ made an even bigger impression on me than his previous band, and, in my humble opinion, remains one of the Great Lost Albums of the 1990s. That was back in 1994. Shortly afterwards Phil Parfitt dropped completely off my radar. For years I searched the internet but nothing came up. Despite this absence though, his music remained an important part of my life.

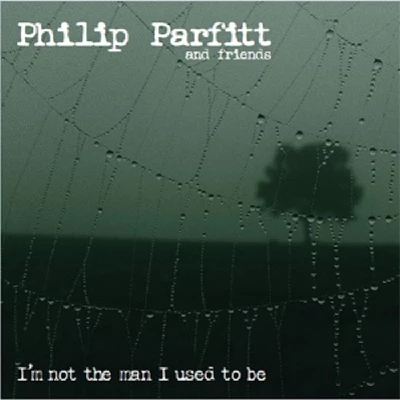

That all changed a few years ago when, out of the blue, a comment appeared at the bottom of a piece I’d written for Pennyblacknusic about Oedipussy’s ‘Divan’ album from the man himself (“Thank you. That is a very decent, considerate review. Well written, researched and executed. Good Luck. Phil Parfitt”). Soon after that in early January 2011, on another blog extolling the virtues of his former band, another comment appeared, This time he stated, “I’ve not stopped writing or recording since ‘Divan’, just haven’t got round to releasing much. I am though planning to get a new album out this year – 2011.” It may have taken an extra two or so years but that album, ‘I’m Not the Man I Used to Be’,his first since the aforementioned ‘Divan’ in 1994, came out on 2nd April on his own Milltonehead Recordings and it’s an incredible return to the fray after an absence of twenty years.

On the eve of its release I caught up with Phil, and what followed was one of the most honest and fascinating insights into the mind of a singer/song-writer that, for me, is one of the unsung heroes of the indie scene of the 1980s and 1990s.

PB: It’s been along time since you’ve been on the music scene isn’t it? You were something of a fixture on the indie-scene back in the 80s and most of the 90s, weren’t you?

PP: Yes – I guess I was. Notorious is probably more apt. There was a period of time when we were reasonably popular with certain proportions of the British music press, and a little bit of the European music press and in the States too.

PB: I remember in particular a certain ‘Sounds’ cover feature and a Jesus and Mary Chain tour.

PP: That’s true. We also, around that time, played with the Pixies. We played with My Bloody Valentine. And quite a lot of other people around that time too.

PB: You mention the Pixies and My Bloody Valentine. Both have made comebacks to great critical acclaim. Is it frustrating that people don’t remember the Perfect Disaster in such a light?

PP: It isn’t really frustrating in that most of the people who did manage, by hook or by crook or by accident, to see the Perfect Disaster actually liked them. And the reason we were chosen to do the Mary Chain tour and play with the Pixies and My Bloody Valentine was because those bands appreciated us. The fact that we didn’t actually ever break into another level was probably more to do with not really being on a fashionable label, and as well maybe not having the kind of infrastructural support behind us that some of those other bands did.

But it never really bothered me we didn’t become super popular. The only thing that sort of got me a little bit at that time was that we, as a band, didn’t really fulfil our potential in terms of the goals we set ourselves.

PB: If you listen back to albums such as ‘Up’ and ‘Asylum Road’, they haven’t really dated at all. Perhaps in the same way that the Velvet Underground’s albums haven’t. You weren’t a fashion band back then, and so you were never in fashion to go out of fashion, I guess.

PP: I think you are spot on there. We didn’t really ever set out to be contemporary when we were making music. We just made the kind of sound that we wanted to make. We didn’t really think that “Is this of the moment?” In fact we probably were a little bit out of the moment most of the time.

But we obviously had a guitar-based sound but, personally speaking, I quite fancied the idea of doing stuff that had orchestral augmentations. Like cello, violin and double bass and various other organic instruments. The idea of trying to be contemporary never really occurred to us. We just wanted to make the kind of music we thought was cool, and if anyone else got into it that was a bonus. But essentially it was our tool to express ourselves artistically.

PB: It must be a bit frustrating when every band under the sun has reformed and had its back catalogue reissued when you’ve got a fantastic back catalogue, and that in a way you are being held ransom by Fire Records who don’t appear to want to do anything with it.

PP: No comment (Laughs). With respect to this back catalogue, I don’t actually own the rights to release all of those records myself. There are plans afoot to release some of them. And we are trying to speak to various elements of various labels which will enable access to those albums. But I can’t speak for other people and why Fire may, shall we say, be reluctant to release any back catalogue. As far as I’m aware, they have maintained that there isn’t sufficient interest for them to do so.

So reading between the lines, this means that there isn’t any money in it. And if anyone from any of the other labels decides to tell me otherwise, then I’m all ears. The door isn’t closed, but then again in these days of immediate access to anything that has ever been released, the number of people prepared to put their hands in their pocket to buy a re-released vinyl album or even a hard copy of a CD are fewer and fewer. Even thought it is a growth industry, there are many more artists available to choose from.

PB: Having said that though, the fans of the Perfect Disaster were very much record buyers and still very much record buyers, no?

PP: The people who are in contact with me, both new and old fans, are in fact record buyers or vinyl junkies or whatever you want to call them. And they are very much interested so they tell me. So the door’s not closed. I’m pursuing those avenues, and hopefully, in the not to distant future, I will have the rights to release all of my music.

PBM: We were talking before, and I found it really ironic that you haven’t even got a copy of your Oedipussy album!

PP: The reason I don’t own a copy of it is only because I had quite a lot and I gave them all away to family and fans, thinking that I could always lay my hands on more. But when Handsome Records, which was a subsidiary of Chrysalis, decided not to re-press the first album, it was then a finite stock which was exhausted.

PB: It was and still is an incredible album. It’s one of my personal favourite albums of all time (See Pennyblackmusic Re:View piece)

PP: It’s funny to hear someone to speak about something that I’ve done in that way because I am aware of all of the music that has been released. There is an amazing amount of stuff out there, so if someone says that to me about something that I’ve done I’m a bit kind of speechless in a way. I believe in it. I put my heart and soul into everything I do but that doesn’t mean that I’m expecting other people to like it, so I’m a bit surprised when people do like it.

PB: Were you frustrated that it didn’t get the critical acclaim the album clearly merited? I’m not talking about thousands of sales but just more recognition. I could almost draw a parallel with the Velvet Underground who weren’t popular or sold many records when they were around.

PP: It’s hard to imagine a time when the Velvets weren’t popular, isn’t it? When I was first into the Velvet Underground I was literally the only other person other than David Bowie, I thought, who knew the Velvet Underground existed. Of course then Lou Reed had ‘Walk on the Wild Side’ which was obviously a massive hit and then that kind of exposure made him a household name in the artistic world in the UK. It was a wide exposure, but at the time when I first heard of the Velvets I think I was a kid into Bowie, and he was playing stuff like ‘White Light/White Heat’ and ‘Waiting for the Man’ on a few BBC Sessions, and I thought. “Wow” because I was really into Bowie and “This is really amazing stuff and I’m must check this out”. Of course, once I had, there was no turning back.

But with regard to my own stuff, when I make an album or write a song, at the time it’s actually passed the moment of creation it’s almost like it doesn’t belong to me anymore, even though I am very close to it and can do anything I like with it. When I put it out I wonder why I’m doing that. It’s not like I’m putting the record out to expect mass appreciation of what I’ve done, but obviously, like any artist, I’m not putting it out for it to be completely ignored.

But at the same time there is a kind of inner self-preservation order in place that means that I have to guard myself, to a certain extent, that I need to expose my work, but I’m not really sure of why I want to do it. It’s really difficult to explain. It’s an amazing question as it’s almost like a psycho-analytical question.

PB: One thing I get from the way you write is that it is not in any way contrived and is more a stream of consciousness.

PP: It’s always like that. I pick up the guitar and I strum a phrase or a motif, and then usually a melody will present itself and I will grab it, and some kind of lyrical structure will come from that. The song will often write itself almost, as if I’m a medium to this kind of exploration of thought. Sometimes I don’t really even know what the songs are about until much later. Sometimes I kind of have an idea in my head of something that’s touched me then I try to write about that. Once the thought processes are rolling along as regard to the lyrical content it kind of takes care of itself. Often when I look back, maybe a few weeks or a month later or a year, I think, “How did I write that? What was going on?”

PB: It’s amazing how songs sometimes appear to come out of nowhere, isn’t it?

PP: Normally songs come out of a feeling. The way I approach writing music is as if I’ve never written anything before so when I pick up the guitar. Because I’ve been doing it for so long there is a sort of automation involved. Then I switch myself on and go into that kind of mode, and then I’m in explore mode and I let it go free.

PB: Coming back to Oedipussy again, did you do a lot of touring with them?

PP: We didn’t tour very much. We played quite a bit in London, we toured around the UK and we played a few dates in Europe.

PB: Sadly I never saw Oedipussy live. I remember you were booked to play the Leadmill in Sheffield but the gig got cancelled.

PP: At that particular time we were touring with some Canadian band. It was a record-company contrived double-bill tour. We clearly weren’t very well suited. They were very nice people, but we didn’t go together musically. We went down okay and played pretty well, but what was happening was it was quite a difficult time as the record company wanted us to move into a certain kind of touring-band mode, but the support wasn’t really there.

When the support did come in, to be fair to them, they came up with this idea that they would help us with touring, so we recorded a second album and we delivered the album, and they said they loved it and everything was looking good and was in place. We even did some remixes. They put out feelers for people to do remixes and some of them came out okay, and then it was all going ahead and there was a release date, and we did a single and then they decided not to release the album. It was an accountant’s decision and a “If we’re really going to make this thing happen then we need to spend X amount of pounds,” and I think they had other fish to fry at that time and that was that. One minute the managing director of Chrysalis was coming to a show and saying “Fuck me! That’s the best band I’ve ever seen” and licking my ear, and the next thing I know they’ve decided not to release the album.

PB: Was that a pivotal point in the demise of Oedipussy?

PP: After that there was nowhere to go with it. They didn’t want to proceed, but I was still signed to Chrysalis in a publishing arrangement which I managed to get myself out of. And then I moved on to do other things. I did a whole other album of stuff that is yet to see the light of day with another kind of guise where I teamed up with a woman who was a really good singer, and I even did a few gigs with that outfit. That was called Littleweed.

PB: When was that?

PP: That would have been around 1999. I started working on the material for it in 1998. The first few songs were from when the Oedipussy thing came to a close. Chrysalis had decided they didn’t want to release the second Oedipussy album and I was already working on another album, so I had a number of songs that I adapted for Littleweed.

PB: That was completely under my radar. The last thing I knew about was Oedipussy and 1994’s ‘Divan’ album.

PP: There was a lot of interest around it at the time as this girl sounded vaguely like Beth Gibbons from Portishead. The songs were just me and my normal paraphernalia, writing stuff that I write about. There was a guitar and samples – not in a dissimilar manner to the ‘Divan’ album but it just had a slightly different angle. But it didn’t happen for various reasons.

I just wanted to record an album and put it out, but the person I was working with [Tina Bell] wanted to put it in a live format so we did this. We spent quite a bit of time finding people and working it up, and then I think that she realised that it was a long haul way of doing stuff, and I think that was quite daunting. By that time I could see the writing was on the wall and it wasn’t going to work. There were hundreds of bands with five bands on a bill in London. It was really grim and totally pointless as no one was going to see them. I was trying to have a band with a gorgeous looking woman at the front and it wasn’t me. I could see it wasn’t going to work, so I just pulled the plugs on it. It wasn’t happening with a natural kind of feel and going in a direction I didn’t want to go in.

PB: What happened after Littleweed?

PP: It took me a while after that to get myself out of this deal I was in with Chrysalis publishing that I didn’t want to be in. This is industry bullshit stuff, and it’s not that interesting. But obviously in terms of how I moved from one space to another, it is relevant, and how then I became very, very worn out with the industry side of things. It just made me think, “What’s the point of trying to do things in this way” when I walking uphill against the wind and getting nowhere fast. So, I decided to stop doing all of that, and I just continued to write and record at home. And then I thought that I wasn’t going to bother releasing anything, at least for a while, as it just seemed at the time, that it was just too much like hard work to actually try and do anything that was recorded to the kind of quality that I wanted to do it to. And also to have an audience. I suppose I came a bit of a recluse.

PB: Are we talking about most of the last decade?

PP: I stopped Littleweed about 2000, and I didn’t do much on a public basis for about ten years.

PB: That’s a long time for somebody who previously was gigging regularly and putting records out, isn’t it?

PP: Yeah. I didn’t stop writing or recording. I just didn’t get to the point where I had a finished product.

PB: When did you start to write the songs that make up your forthcoming album ‘I’m Not the Man I Used to Be’?

PP: Some of the songs, and some that didn’t make it on to this record (about fifty in all) but will be on the next one, are ten years old, from shortly after I stopped doing Littleweed. There’s a couple on there including the last track ‘Have Better Days’ that were written a few weeks before I recorded the album. It was one of those things that happened like that. I wanted to do something fresh and pared back to a couple of elements. So I thought, “I’m just going to do something” and I put that together in a matter of a couple of hours. I kind of like leaving things unfinished until a point in time where I have to finish them and it makes my head work in a way that I appreciate the process.

PB: Once news started to filter out a few years ago that you were writing again I think the first track I heard was ‘Winter is Going to Come’ After all those years since I’d heard new material from you it brought tears to my eyes.

PP: That’s really nice.

PB: When a songwriter that you have really identified with disappears for a long time reappears with new material there is such a weight of expectation and an overwhelming hope that you will like the new material. I remember waiting to listen to that track thinking, “I hope it is good”.

PP: I kind of know what you mean.

PB: You really want to love it and you think, “What happens if I don’t like it?” Fortunately in this case it wasn’t an issue as the song just blew me away. It had all the qualities that made me a big fan of your song-writing all the way back to your Perfect Disaster days.

PP: I write now like I’ve always done, and it’s a gift that I have if it can be called such. I have the ability to put myself inside of something and make it seem as if it’s real. That brings a kind of clarity to the simplest of guitar motifs or lyrical musings. It’s just something I do. I can naturally put myself into a character and make it seem plausible. I don’t mean that to sound pretentious. It’s just that’s my knack.

PB: Some of the songs, like for instance ‘Lines Written’, is very honest. Almost crushingly so.

PP: Yes – it’s really bizarre this kind of thing. The lyrics were written on the 26th of June 2013, just a couple of weeks before I recorded it and it was all written in fifteen minutes. It just happened. It just came like that.

PB: Lyrically it’s up there with some of your best songs.

PP: It’s odd isn’t it? Other things I labour over for hours and hours or weeks and weeks and don’t finish properly and I think, “God, that’s awful,” and then something like that happens and I write it in fifteen minutes, and you think, “Oh, right okay”. After a while I’ll look back at it, and I’ll say, “Bloody hell, what’s all that about?” It just seems to happen like that. I just go into what I call “deeper mode.” I don’t know where it comes from.

PB: There’s certainly continuity with the new album. I’ve been lucky enough to hear the whole LP and, for me, it is very much a natural progression of what has gone before. There’s no radical change in terms of the nature of the songs and how you express yourself, but there’s a maturity to it – hence the title I guess?

PP: I did have a few different titles for the album, but like a lot of things it just appeared to me in one time. I was talking with one of my fellows, and we were discussing the process of how we would deal with recording the songs. It just occurred to me I had made an unconscious decision not to try to do something that I’d done before, even though it was me doing everything that I’d done before.

PB: And you had ex-Perfect Disaster bassist Johnny Saltwell playing double bass and Jonny Mattock playing drums, didn’t you?

PP: And Martin Langshaw. Martin played on ‘Up’ and ‘Asylum Road’. Jonny Mattock played on ‘Heaven Scent’ and toured with us around that time. Jonny we obviously borrowed from Spacemen 3, and before they had a drummer they borrowed Martin from us, and we used to play with those guys quite a lot. I wanted to do this album by reproducing the sound of the songs as they sounded naturally.

What quite often happened in Perfect Disaster was I had a riff and a lyric, and I would show it to the band and we would work it up, and then it would transform itself into the form that it appeared and often, like for example on ‘Heaven Scent’, it kind of bugs me that my acoustic versions of them are better than the band versions.

When you sometimes put things in a band format it changes them and sometimes that’s not so good. There are things in there where I thought it would have been better just to keep them simple. So, with this kind of thing, I had this idea that I wanted to reproduce the sound that was in my head but it was a very quiet kind of sound. And it took me quite a while to find sympathetic players whom I could just gel with.

PB: It is a very gentle album but I also find it very cohesive too. Just like ‘Divan was an incredibly cohesive album with no weak tracks.

PP: It’s a mindset sort of thing. If you get into the rhythm of recording things in a certain way then everything comes together. I don’t look for this kind of cohesion – it just kind of happens.

PB: Sometimes bands release albums and they are very uneven. Often there’s some good songs on there, but as a body of work they don’t really hang together. But, for me, this album is very cohesive.

PP: Well, I kind of think it is. At the same time it is a collection of songs that I’ve recorded and it’s not for me to even wonder whether it is cohesive or not. I recorded these songs and I put them together in a collection, and I called that collection an album, and here it is.

As it goes, the project was recorded over a long period of time compared to what you would usually use to do an album these days. But I started the recording process at the end of 2012 when I went to Paris and I did a few songs with my pal over there. I listened to them and thought, “This can work and so this is how I’m going to do it,” but at that time Johnny Saltwell, Jonny Mattock and Martin Langshaw were not involved. In fact it was just me and my guitar and the songs.

It was at this time that I thought that I want something on here that’s sympathetic to the songs, and then incidentally saw these guys who I worked with, Christoffe Deslignes and Eva Fogelgesang, who are people who are renowned in their own field of medieval music, when I happened to catch them at a concert. I thought, “Wow, this is the sound I’ve been trying to work with in my head but didn’t really know how to do it,” so I approached them and we got together and it just gelled. We thought, “Okay, let’s do this,” and we recorded an album. I had all of these songs so we tried a load of them out and those that worked we kept and I just worked them up.

Then I wanted to augment the sound a bit, so I approached Johnny Saltwell and Martin to see if they wanted to come on board and they said yes, so we took it from there. I came over to the UK a couple of times to record some stuff at Johnny’s place, and we added some drums and some bass, and then because I was there in the UK I got my eldest daughter Candy to sing these vocal parts that were just in my head, and she just delivered them and did her thing with them that made them her, and we worked on that. It just seemed to gel.

It is probably cohesive because we gave it a lot of space to work. We didn’t force the sound by saying “This has to sound like this”. I just did the songs and said, “This is what I want you to do”. Most of it is recorded in my house in France. We just put a microphone up and recorded everything in my lounge.

PB: Are you excited about the prospects of releasing your first publicly available work for 20 years?

PP: I feel really good about it. I’m excited about it but I now just want to get on with the next thing. It’s been a while since it’s been finished. It was only mastered recently, but I finished mixing it last September. Then we had to go through “How are we going to release it?” as I wanted to do a physical release, so I did the usual thing of putting together a label with some good friends of mine. So, we’ve done that and put everything in place. It, however, takes time to do it properly, but we feel like we’ve got something that’s really nice and we want to give it a proper sending off. So, that’s why we’ve done it like that.

PB: What’s your favourite track off the album?

PP: It changes from day to day.

PB: Okay, current favourite then?

PP: I quite like ‘New Timber Hill’.

PB: It’s a very beautiful song and a really organic start to the album. It’s also a bit of a family effort, isn’t it?

PP: Yes, my youngest daughter narrates the poem at the beginning of the song, and Candy, my eldest daughter, sings with me on the chorus part. So, yes, in that respect, it is a family effort. It also means a lot to me that song, as it was written about a time and an adventure I had on New Timber Hill which is a place not far from where I used to live in Brighton, at the back of the town on the South Downs. It’s a tiny village, but the hill itself is a big hill and if you climb to the top of it you can see the ocean on a clear day.

PB: I get a strong sense of the elements running through the whole of the album. The sea, winter and the other seasons. That comes across very strongly in the album.

PP: I’ve always written about things that touch me, so my environment and global issues come into it to a certain extent. My environment as it affects me is reflected in this work. I think that it sounds a bit spacious like that because where I live I’m surrounded by nature and I’m engrossed in nature every day. It’s part of my existence, so it’s probably just natural that it’s reflected in this particular work. If I was living in a tower block in London, I would probably have a different take on things. I just work with what is at hand.

PB: It is a very beautiful album and I hope that this is a big success and the first in a number of albums that we see from you now that you are back in the fray.

PP: It already is a big success in many ways because, for one reason or another, this body of work has got me back into recording and releasing music, so that in itself is quite remarkable because I hadn’t intended to do that again.

And yes, in another way it has whetted my appetite to reconsider all things, so plans are afoot to record a follow up and I am talking with some very exciting people to bring the second album to fruition as we speak. I’m currently speaking with some nice folk from America who I wasn’t aware were such big fans of my stuff so that’s quite exciting. It’s a good period creatively so I’m tapping into what I hope will be a rich vein.

PB: Earlier you mentioned about giving the album a “proper sending-off”. Will that involve taking it out live on the road?

PP: We have plans to do some concerts. We are just going to see how things progress and see if any interesting offers come our way. They don’t have to be big things – they can be small things. We are open to consider all things. It’s a very small operation and we are open-minded as to how we can make it work. I am currently working with a guitarist and it’s sounding really nice. It’s really nice to hear the songs again in yet another fresh light, and this guy is an amazing guitarist. So, if that comes together nicely then we’ll see. I can play the songs as a solo artist or I can play the songs as a duo or as a band. If and when it happens I will also do some old Perfect Disaster songs and some Oedipussy songs too. A set of old and new basically.

PB: Thank you.

‘I'm Not the Man I Used to Be’ is available from iTunes and other digital outlets. A CD version of the album can be ordered from Phil Parfitt’s BandCamp site:

http://philipparfitt.bandcamp.com/

Article Links:-

http://philipparfitt.bandcamp.com/

Band Links:-

http://philipparfitt.bandcamp.com/

Picture Gallery:-