published: 30 /

6 /

2013

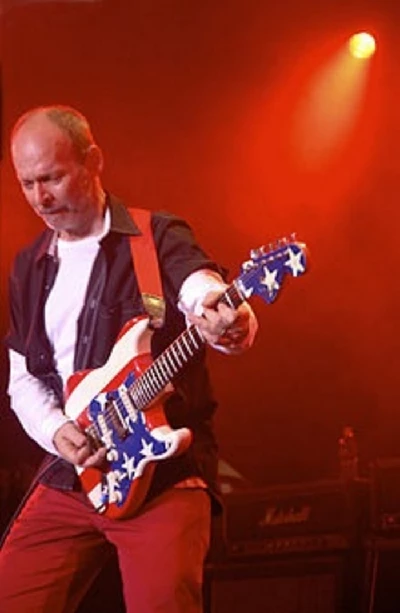

John Clarkson chats to MC5 guitarist Wayne Kramer about his influential band, and his charity Jail Guitar Doors which brings musical equipment into prisons

Article

Singer-songwriter, seminal guitarist and ex-con Wayne Kramer was the co-founder and band leader of the MC5.

The trailblazing group, which also consisted of Rob Tyner (vocals), Fred “Sonic” Smith (guitars), Michael Davis (bass) and drummer Dennis Thompson, formed in 1964 in Detroit when its members were all in their teens.

They quickly attracted notoriety both for their incendiary live shows and their militant left-wing politics which advocated free love, drug use and violence against authoritarian forces.

The MC5’s first album, the primal ‘Kick Out the Jams’, combined together elements of jazz, psychedelia and garage rock, and, released in early 1969, was a live album recorded during two shows at Detroit’s Grande Ballroom. Songs from it such as ‘Motor City is Burning’, ‘Come Together’ and the fiery title track have since come to be seen as classics.

Shortly after its release, however, their manager John Sinclair was jailed after being in found of possession of marijuana. Hudson’s, a Detroit department store, also refused to stock ‘Kick Out the Jams’ because of Tyner’s use of swear words on it, and, when the MC5 responded by placing a full page advert in a local paper proclaiming “Stay alive with the MC5, and fuck Hudson’s!”, they were dropped by Elektra, their record label.

The group released two more albums, ‘Back in the USA’ (1970), which with its abrasive, aggressive sound was a huge influence on the punk generation, and ‘High Time’ (1971) which proved an eventual similar influence on hard rock bands. Neither of the two albums, however, sold well at the time, and they were also dropped by Atlantic. Several of its members now had drug habits, Burnt out and playing to diminishing audiences, the MC5 broke up after playing an under-attended farewell concert on New Year’s Eve 1972,

Wayne Kramer was convicted in 1975 for selling cocaine to two undercover policemen, and spent two years in a prison in Kentucky.

When he was released from jail in 1977, Kramer moved to New York and started a solo career, but did not put out an album, ‘Death Throng’, until 1991. After that, Kramer went on to release over the next eleven years another eight studio albums of punk and hard rock, first of all of on Bad Religion guitarist Brett Gurewitz’s Epitaph Records, and then latterly on his own label Muscletone.

Rob Tyner had died of a heart attack in 1991 and Fred “Sonic” Smith from alcoholism in 1994. In the years since the MC5 had broken up they had attracted the interest of a new generation of bands including acts as diverse as Rage Against the Machine, the Damned, Radio Birdman, Primal Scream, Henry Rollins, Pearl Jam and Jeff Buckley, and several of them had covered their songs and especially ‘Kick Out the Jams’. In 2003 the remaining members of the MC5 reformed the group, initially with a succession of guest vocalists including Mudhoney’s Mark Arm, the Cult’s Ian Astbury and Lemmy from Motorhead before they settled on “Handsome” Dick Manitoba from the Dictators as their singer. They played several world tours before Michael Davis died from liver failure last year,

While he remains active in music, Wayne Kramer, who is now 65, spends as much time these days running his charity Jail Guitar Doors. Jail Guitar Doors takes its title from a 1978 Clash song, which makes reference to Kramer’s jail years, and was first established by Billy Bragg in 2006 on the fifth anniversary of Joe Strummer’s death. Kramer has run its American branch since 2009, its aim being to provide musical equipment for the use of prison inmates. Kramer also plays occasional concerts in American prisons, taking with him a revolving cast of other musicians that have included Bragg and ex- Guns ‘n’ Roses guitarists Matt Sorum and Gilby Clark.

Wayne Kramer was in Britain at the end of June to make a guest appearance with the Danish surf trio The Good The Bad, where at the Blues Kitchen in London they played together an extended version of ‘Kick Out the Jams’. Pennyblackmusic spoke to Wayne Kramer the day before that gig and began by speaking to him about that classic song.

PB: ‘Kick Out the Jams’ is often seen as being a song about breaking down restrictions and barriers. Another story that has, however, circulated over the years was that phrase was initially directed at another group who you were sharing a bill with to get off the stage. What is the real story of that song’s origins?

WK: It was one in a whole string of songs that we wrote in the period of ‘67/’68. We had all just moved in together. We were teenage guys, and it was very hard to get everyone together to rehearse because we lived all over town. We didn’t have any money, and no one had a car, and we didn’t have a place to rehearse, so from a practical point of view it made a lot of sense for us to move in together.

Once we all lived together it was much easier to write songs together, and ‘Kick Out the Jams’ was one of a handful of songs that we wrote in that period. Mostly Rob Tyner and I wrote the songs sitting at the kitchen table.

The sentiment of that song had to do with our frustration at seeing other bands that we didn’t think that were as accomplished as they should be, but we were also kind of yelling at ourselves, telling ourselves that we should work harder at what we were doing.

PB: It seems from the outset that the MC5 had a very strong work ethic.

WK: We are from Detroit, which is the home for organised labour and the unions. We honour hard work there.

PB: The late 1960’s was a unique period for music in Detroit. There were yourself and the Stooges, but all these other people came out Detroit and Michigan at the same time such as Alice Cooper, Bob Segar and Grand Funk Railroad. Motown was also at is peak. You were all very different from each other, but you each had an impact. Why do you think things kicked off in such a way that they did in Detroit in particular at that time?

WK: Detroit didn’t have the baggage of New York or London or San Francisco or Paris. Detroit was an industrial city, and the general sense was that nothing cool could come out of Detroit because it was a manufacturing city. Those of us from Detroit didn’t see things that way. We thought - and I thought - that my analysis was a as good as anybody else’s. I was as smart as anybody else. I was as creative as anybody else, and my ideas could stand up in an arena alongside anyone else that was doing that kind of that work at that kind of time. As Detroit was such a hard place to break out of, it forged the urge with me to be stronger.

PB: And do you think that was the same with everyone else?

WK: I think so. Berry Gordy was up against the same thing. All the other Detroit rock bands were up against the same thing. We kept being told, “You can’t be cool. You’re from Detroit,” and we thought, “What’s wrong with us? We are good as anybody else, and maybe a little better.” I thought some of our ideas were more advanced than the stuff coming of those other cities.

PB: The MC5 were once described as “the guys who chopped down the trees to clear the dirt roads to pave the streets so that the rest of us can drive by in Cadillacs.” Would you agree with that statement?

WK: Like we were like the snowplough to get the bumps out of the road (Laughs)? Maybe? That is flattering. All I know is that we invented ourselves and made it up as went along. If we illustrated then that such a thing was possible, then that is not such a bad thing.

PB: Does it disappoint you forty years on that you were not more successful at the time or are you content with the fact that, like the Stooges and the Velvet Underground, that you pioneered the way of the musical landscape of the future?

WK: I have to be content with that because that’s reality. The reality is that things have played out the way they have. I don’t regret the past, but I also don’t close the door on it. I have to be able to look back and say where did I make a mistake? Where did I get it wrong? And then I have been able to kind of use that as a guide to the future, to not make those kinds of mistakes again.

PB: It is interesting that you should say that because the main aim of your charity seems to be to encourage prisoners not to make the same mistakes again.

WK: The transformative part of art in the prison environment can open the door for prisoners to look at themselves, and to undertake that self-examination – for them to contemplate and think, “How did I get here and what do I need to do make sure that I never come back to prison again?”

That is really the message of Jail Guitar Doors – that a guy can sit with his guitar and tell his story, that he can sit in a non-confrontational way and through the telling of that story start to see himself in a different way and how he fits in the world as an artist, rather than just as a number or a bed space or the guy who always gets himself into trouble.

PB: Billy Bragg set up Jail Guitar Doors in Britain. How did you become involved and end up running the American part of of it?

WK: I guess that I became involved because I went to prison myself, and the Clash wrote a song about it, and then it circled back around (Laughs).

One day I ran into Billy Bragg. He was telling me that he was doing this work in England, and that he had named his initiative after the Clash song about me going to prison, and I thought, “This is just what I am looking for.” I think I can hardly do better than be of service to my fellows, and a lot of my fellows are those guys serving those sentences.

I am also uniquely positioned. I am a musician and I am an ex-convict. I am able to be the bridge between these worlds. Jail Guitar Doors was musician founded and musician operated. What we do is reach out to those musicians behind the fence. If one musician can teach another, then it goes a long way towards the transformation necessary to not come back to prison again.

PB: How many instruments have you actually put into American jails so far?

WK: I think we have put in probably more than three hundred, but we have got a long list ahead of us. Fundraising is always a challenge. In America we have 2.3 million people in prison and half of them are non-violent drug offenders who really shouldn’t be in prison in the first place. We need that personal change that art can produce in the prison, but we also need political and legislative justice as well.

PB: One of the most difficult things for you in doing Jail Guitar Doors must be breaking down public preconceptions. You have said that 50% of people are in for drug-related offences, and that they shouldn’t be in jail. Has it been hard breaking down that idea that everyone who is in prison is not a murderer or a rapist?

WK: It is a common misconception because it is a conversation that most people don’t want to have. You want to kill a party you bring up the subject of prison (Laughs). I have seen people flee from the room when that conversation comes up. It is a highly charged emotional issue, but it is a conversation worth having,

I believe that it is extreme to believe in the rule of law, because what we were doing in America is not justice and in fact undermines respect for law. We lock up people for the most severe sentences in the world for non-violent substance abuse offences. Personally I think even the sentences for violent crime are too damn long.

People have every right to want retribution and revenge. I understand that and that that connects to one’s personal sense of justice, but at the same time state and justice policy has to be tempered with mercy. We say that it is, but we don’t act that it is.

We have to ask what at what point does a person pay his debt to society? At five years, ten years, at twenty years. The idea of sentencing someone to life without parole seems to me to be merciless. I just think that this is a conversation that we need to have.

PB: Have your personal politics changed a lot since the days of the MC5?

WK: Yeah, they have. My views then were pretty naïve and heavy-handed (Laughs). I would like to think on one hand that that they are more nuanced and wiser today, but at the same time I struggle more with my own cynicism.

Even the work I do in Jail Guitar Doors, I feel that sometimes it is just a temporary distraction from meaninglessness. I look at the world and I see a planet that is over-infested with human beings. The reproduction of human beings is actually going to destroy the species eventually (Laughs). In the 1500s there were a billion people on Earth, and now there is nine billion people and no end in sight. We are reproducing at a level which I don’t think is sustainable. It won’t affect me because I will be dead and gone, but it is going to affect somebody at some point.

PB: The MC5 reformed for several tours with Michael Davis, Dennis Cooper and yourself between 2003 and 2012. As Michael Davis died last year, will you and Dennis be carrying on or do you see that as the end of things?

WK: Dennis has got some health challenges, so I don’t think he is going to be performing in the future but so far so good here. I am in pretty good shape for a man of my age (Laughs), and, yeah, I want to do some MC5 dates.

I enjoy playing that music and I enjoy playing that music for this whole new generation of music fans. It is fun. I dig it. I think that the MC5’s message of possibility is worthwhile, and I am happy to carry it off.

I want to play really to the end. Music isn’t really tied to being young. You can continue to develop your technique. You can continue to make your ideas more advanced or challenging and more unorthodox and passionate the longer that you go on. Most artists continue working right to the end, and I don’t see any reason for me not to do that as well.

PB: You solo career has gone on hold during the last few years. You have put out a solo album now since ‘Adult World’ in 2002. Are you still finding time to write your own material?

WK: Well, actually I do have a new album that will be out in January. We are just forming together a new label to release it on. I am not sure really that you call it a label because I don’t think that labels actually exist anymore. I think of it as more a conduit or a portal, and what I will be doing is reissuing all of my solo stuff and a lot archival MC5 stuff through it.

As well as the new album, I have got a second one written and I also have got a third one in the embryonic stage. Most of my writing has been for TV and film for the last few years, but I am looking forward to get back to touring and playing.

PB: Thank you.

Picture Gallery:-