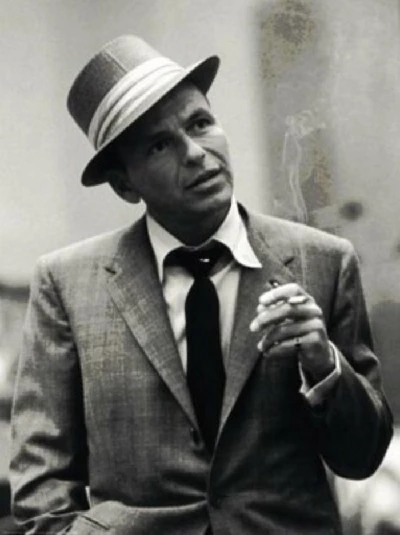

Frank Sinatra

-

Frank Sinatra in the Fifties

published: 1 /

6 /

2010

Jon Rogers reflects upon the musical career and comeback of Frank Sinatra in the Fifties

Article

The Fifties really started for Francis Albert Sinatra in 1953 – the day he signed a seven-year deal with Alan Livingston, then vice president of A&R at Capitol. Against the overwhelming advice the Sinatra fan had been given against signing Ol’ Blue Eyes who was before then just another washed up crooner, barely able to land a regular nightclub gig.

Livingston had thrown Sinatra a lifebuoy when no one else would and it was something of a gamble but one that paid huge dividends in both critical acclaim and sales. Even Sinatra knew he was in trouble, later reflecting to 'The Los Angeles Times': “I stunk. My voice was shot. I knew it and you knew it and everyone knew it.” And according to Livingston, before he signed to Capitol Sinatra was “meek, a pussycat, humble... broke, in debt... at the lowest ebb of his life.”

Due to Sinatra being down on his luck the deal was heavily stacked in Capitol’s favour and according to Anthony Summer and Robbyn Swan in ‘Sinatra: The Life’ the deal only gave Sinatra a $1,000 advance, tied him in until the end of the decade and Sinatra was required to pay all studio costs. Sinatra apparently put his moniker on the document at Lucy’s Restaurant in Hollywood on 14 March.

The decision to sign Sinatra didn’t go down well at that year’s company convention. Apparently when Livingston made the announcement there was an audible groan from the gathered 200 odd salesmen, local managers and marketing types.

And things didn’t start well. The initial four songs he cut at Capitol’s studios on Melrose Avenue were nothing special and it would even be years before two of them were even released. But it took his partnership with arranger Nelson Riddle for his career to gain a new lease of life.

‘Young at Heart’ reached number 2 in the Billboard singles charts early in 1954 (it wasn’t so successful in the UK, only reaching #12 and was only in the charts for one week). It was the start of what was a very good year for Sinatra. He got an Oscar for ‘From Here to Eternity’, the album ‘Songs for Young Lovers’ was in the charts and peaked at #3 in the USA. In the end of year polls, Metronome proclaimed him singer of the year, 'Down Beat' magazine named him most popular male vocalist and a poll of disc jockey’s voted him top male vocalist.

Sinatra’s career at Capitol really took off when he teamed up with Riddle to record ‘I’ve Got the World on a String’. On hearing the recording of the song Sinatra enthused wildly: “Jesus Christ! I’m back, baby, I’m back!”

The Riddle Sinatra partnership – that lasted up to 1962 – really marked the high watermark of Sinatra career, spanning nine albums. Some, like ‘In the Wee Small Hours’ and ‘Songs for Swingin' Lovers!’ would form part of the bedrock of American popular music and really marked Sinatra’s golden age putting him up there with the all time greats like Elvis Presley and the Beatles.

While the two would work closely together and Sinatra praised Riddle as “the greatest arranger in the world” the concept and direction of each album would be Sinatra’s. He would decide the ordering of the songs, perhaps picking a particular mood for a particular song as well as the pacing of an album. And Sinatra was always professional in the studio, being well-versed in studio recording techniques and would always be ready with an observation on how to make improvements, sing a particular line with a different phrasing or to make comments about a particular tempo or tone.

Over the years Sinatra would invariably try to book the same musicians and keep to a recording schedule of 8 p.m. to well after 12 in the morning, usually being fuelled by coffee and cigarettes.

Sinatra relied heavily on giving old standards a new lease of life – thanks to Riddle – and giving each album a specific feel by picking the mood and drive with the styling reflecting both of their interest in big bands and jazz. There was the sadness of ‘In the Wee Small Hours’, the romance of ‘’Songs for Swingin’ Lovers!’ and the mixture of hope and regret in ‘Swing Easy’.

Not only did his sound change but his new contract spurred him on to a complete professional and personal makeover. “I changed record companies, changed attorneys, changed accountants, changed picture companies and changed my clothes,” he once reflected.

Sinatra had always worn hats but now they became his trademark. How he wore them was usually an indication of his mood - albeit tipped back or pulled down low over his face. And hats also covered up his increasing baldness and he even had someone spray “hair colouring” on to his ever-expanding bald spot.

Even Sinatra’s voice changed. Whereas his son had considered his father’s voice “romantic, tender, wistful” but in 1953 he noticed that it had changed drastically. “Gone was that soft, gentle, dreamy and crooning sound... From that day forward his sound was different, Defiant, assertive, even forceful.” Part of that might have been a conscious decision but part was just his voice changing as he got older – he hit 40 in 1955 – and his heavy drinking and smoking didn’t help either.

And lyrically there was a change too. From his crooning days which his son would view as “merely pleasant musical conversation” now he was making a “statement”. Now, lyrics were “first, always first. Not belittling the music behind me, it’s really only a curtain... The word actually dictates to you in a song, it really tells you what it needs.”

What that was, according to Riddle, was sex: “Music to me is sex. It’s all tied up somehow. I always have some woman in mind for each song I arrange.”

For Sinatra a lot of the time he had Ava Gardner in mind.

His often obsessive love for Gardner, whom he had married in 1951 but was separated from in December 1953, would colour many of his Capitol albums. Perhaps none more so than the heartbreaking ‘In the Wee Small Hours’, produced by Voyle Gilmore, in 1955. It’s one of, if not the, break up albums of all time, certainly up there with Bob Dylan’s ‘Blood on the Tracks’ full of unrequited love and loneliness. Most of the songs were recorded in early 1955 when he knew his marriage to Gardner was well and truly over. There’s the barfly confession of ‘Can’t We Be Friends?’ the melancholy of Duke Ellington’s ‘Mood Indigo’ and the pleading of Cole Porter’s ‘What Is This Thing Called Love?’. But possibly the biggest tear-jerker was ‘I Get Along Without You Very Well’:

“I’ve forgotten you just like I should,

Of course I have,

Except to hear your name,

Or someone’s laugh that is the same

But I’ve forgotten you just like I should.”

Gardner certainly got under his skin and his passion for her would come and go for over twnety years sometimes pursuing her around the globe to places like London and Madrid. Sinatra’s apartment in Wilshire and Beverly Glen in Los Angeles, looked, by all accounts like a shrine to the film star.

According to valet George Jacobs’ memoirs: “There were pictures everywhere, in the bathrooms, in the closet, on the refrigerator.” And things, apparently, were no better at his Palm Springs home either. Often Sinatra would be found in the early hours in a darkened room, surrounded by pictures of her and the remains of a bottle of brandy nearby.

The maudlin album sounded just like that. And all too often he gets filed under ‘Easy Listening’ in record shops for some reason.

The album was also groundbreaking in that while it was initially issued as two 10” records it was then reissued in a 12” format, helping to usher in the arrival of the album. And while previously albums had been little more than a collection of songs, ‘In the Wee Small Hours’ was effectively the first concept album with a theme running throughout all sixteen songs.

In the same year rock ‘n’ roll was just getting underway. Bill Haley’s ‘Rock Around the Clock’ entered the UK charts and Elvis Presley released his third and fourth Sun singles. Both Bo Diddley and Chuck Berry make their first US chart appearances and Little Richard got all ‘Tutti Frutti’.

But while ‘In the Wee Small Hours’ was all night time darkness the following year’s ‘Songs for Swingin’ Lovers!’ was completely different. It briskly skips along on a fine summer’s day and brims with joie de vivre, harking back to earlier albums ‘Songs for Young Lovers’ and ‘Swing Easy!’.

Songs like the opener ‘You Make Me Feel So Young’ and ‘You Brought a New Kind of Love to Me’ simply glide along on a cloud of air. There’s a cheeky playfulness there too with Sinatra cocking the listener a knowing wink with ‘Makin’ Whoopee’. Released in March 1956 in the US (and in June in the UK where it reached #12) it’s perhaps the archetypal blueprint for the three-minute pop song.

The fiteen track album clocks in at 45 minutes. It’s hard to surpass that brilliant pop craftsmanship from Sinatra’s gentle intonation and Riddle’s light-handed orchestration. In Rolling Stone’s 500 greatest albums of all time the American publication placed the album at #306.

In the 50s and part of the early 60s as Chris Rojek’s cultural study of the singer says, Sinatra “became an American Caesar: king of the Rat Pack, champion of the public, and dictator to the press.” His songs became part of “the vernacular of both elite and popular culture in the way that poetry used to before the invention of the phonograph.”

Part of Sinatra’s success was down to simply to his work ethic as well as ability. Over Sinatra’s time at Capitol he would provide them with dozens of hit singles, a total of 17 hit albums, three of which would reach the top of the charts and five #2s. In 1958 and 1959 he released three albums per year and seven (including compilations) in 1957. And he still found time to make three films in 1957 and two each in 1958 and 1959. And he made five films in 1955 and four in 1956.

Whatever criticism can be levied at Sinatra, being lazy wasn’t one of them.

Quantity doesn’t mean quality though and while Sinatra’s standards for the most part were extremely high with albums like ‘Where Are You?’ and ‘No One Cares’ some of the later ones in the 50s left much to be desired despite being huge hits. ‘Come Fly with Me’ in 1958 is mediocre at best and very lightweight and seems to be little more than a marketing attempt to cash in on the growing boom in long-distance air travel with the likes of ‘South of the Border’ just sounding cheesy. And the title track and ‘It’s Nice to Go Trav’ling’ just sounded like he’d been sponsored by some tourist board. The album though made it to the top of the charts and stayed there for five weeks and remained in the Top 50 for 70 weeks.

Similarly the following year’s ‘Come Dance with Me’ won a Grammy award for the best album of the year and reached the second spot in the charts on both sides of the Atlantic. but the big band sound was big and brash and Sinatra sounded like he could do that sort of thing in his sleep – and sounded like he was. This was Sinatra by numbers.

His film quality was equally erratic. For every ‘Man with the Golden Arm’ and ‘The Manchurian Candidate’ (actually made in 1962) there was rubbish like ‘Johnny Concho’ and ‘Never So Few’. Some of which Sinatra surely must have done for the cheque at the end.

Sinatra’s success didn’t just stop when the 50s did and he carried on well into the 60s but he was increasingly out of step with youth who had once seen him as the embodiment of cool and hip. And while later on he flirted with pop and rock music with recordings of ‘Love Me Tender’, ‘Yesterday’ and ‘Mrs Robinson’ he rather held rock ‘n’ roll in contempt. When he founded Reprise Records in 1961 he refused to sign rock acts. For Sinatra this music signified the end of the big band/nightclub era in which he had excelled. Rock ‘n’ roll signified a fundamental shift in the musical tastes of youth and Sinatra held it in low esteem:

“It is sung, played and written for the most part by cretinous goons and by means of its almost imbecilic reiterations and sly, lewd – in fact plain dirty – lyrics... it manages to be the martial music of every sideburned delinquent on the face of the earth.”

Coming from Sinatra this was just hypocritical. Even at the start of his career he was an overtly sexual singer, standing in a suggestive manner, cradling and caressing the microphone and seducing his largely female audience with his velvety vocals. And with the Rat Pack of Dean Martin and Sammy Davis Jr he projected a bravura masculine lifestyle of endless promiscuity and conspicuous consumption.

While Sinatra saw his craft in terms of being a well honed and carefully constructed art, rock ‘n’ roll was wilder, much more spontaneous and freer and what Sinatra would see as indiscipline. Simply Sinatra was left behind.

In a wider cultural sense Sinatra embodied America’s postwar consumer culture. The sense that economic prosperity will bring with it happiness and help solve social problems and that scientific and technological advances will benefit everyoned. To Sinatra, America really was the land of the free and opportunities were there for all no matter what colour or beliefs. [And all this with his connections to the Mafia, threats of violence and intimidation...]

The 60s, particularly towards the later part of the decade, heralded in a different ethos that was more questioning and sceptical of the prevailing ethos and were more likely to drop out of the American Dream rather than buy into it. For many Sinatra simply became a symbol of a bygone era that they simply couldn’t relate to. But even today Sinatra’s voice still holds the listener captive and he was never on better form than in the 1950s.

Band Links:-

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Frank_Si

Picture Gallery:-