Miscellaneous

-

London's Burning

published: 15 /

4 /

2007

In the first part of a new three part series, in which Adam Wood examines the rise of 70's British punk, he looks at the social and the political factors of the country at the time which both generated and developed the movement.

Article

Britain is obsessed with the Second World War, and for all the wrong reasons. It is not because of the sacrifice or the defeat of tyranny anymore. Indeed those that were there are gradually dying out. Rather it is what the war gave birth to that leads the fixation, millions of them.

The baby boomers, born with hope and inheritors of a mass affluence, control our culture, our tastes, our music. We have a baby boomer government and a media that still celebrates plain, formulaic pop art as revolutionary. And worst of all, we still have to listen to the Beatles.

The UK doesn’t have a choice, even today. The music that boomers grew up to still holds more sway than any other, and it is awful. The decay of their ideals is no better symbolised than in the naïve, self-inflicted disaster of Altamont and in the endless regurgitations of idiotic idealism by a gang of bloated money-grabbing ex-junkies called hippies.

But there has always been an undercurrent resenting the mainstream and clamouring for a slice of the limelight. In the 1970's, a generation of young men and women had had enough. They started making their own, stripped back art, fashion and music. Most importantly, they stood up and said: “Never trust a fucking hippy.”

They were the punks.

With a name that to the hippie generation meant a rent boy, the punks hated everything that the media elites and the political old guard stood for. They belonged to the Blank Generation, a group not welcome in anyone’s plans, a group told to put up with what they had because that was all they were going to get. The Blank Generation was drawn predominantly from the young urban and suburban working class, most notably in London, an arena of great political protest in the mid to late 70's. Class characterised the Blank Generation, as did its do-it-yourself music, a form that allowed the least technically able musician to be able creatively articulate themselves. Style was also key, through original clothes and the imagery of poverty and filth; the Blank Generation was able to enact a kind of semiotic guerrilla warfare.

Punk was a cultural, political and social movement that attempted to break down barriers in art and in life, to create a community of the displaced in a society that negated them. Punk, however, was not a politically revolutionary movement; it encouraged young members of society to take on the DIY ethic and create a different world for themselves rather than to overthrow British society as a whole. This is because punk cannot be anything but a product of the environment from which it was born. For all its innovation, the punk movement is still susceptible to the whims of wider society and its forms; capitalism, the press and the aggressive reaction of some of its members.

The experience of Britain in the 1970s' was an experience of drawn out decline and decay, the consensus politics of the 1960's was falling apart, the notion ‘You’ve never had it so good’ couldn’t have been further from the truth. Tensions in the streets of major cities were running high. The National Front’s aggressive and provocative tactics cast a shadow over the communities which it menaced, and its clashes with opposing demonstrators brought a violence to the city streets which had been unknown since the 30's. This antagonism and street violence became crystallised in 1974 with the death of Warwick University student Kevin Gately who was killed protesting against the National Front in Red Lion Square, London.

As extremism and street violence was becoming more and more commonplace, Prime Minister Ted Heath’s failures had left many believing that Britain was ungovernable. Fears of immigration, IRA mainland bombing and doom-laden tabloid headlines added to the population’s feelings of despair. The Labour Party came into power in 1974 with a tiny majority and the almost impossible task of stabilising the economy as well as implicating a socialistic programme of government.

The social and economic problems of Britain, however, could not be solved simply by government legislation. Unrest was caused by much more than Heath’s perceived shortcomings as a Prime Minister. The problems of society ran far deeper than that. A process of fallout from the 1960's had occurred; a sizeable part of the generation born at the end of the late 50's and early 60's were coming into maturity, without the promise of a job for life, without stability and without a sense of community.

The rebellious nature of late 70's counter-culture was by no means a snap reaction to the dissolution of the Winter of Discontent, its roots lay in an outright rejection of the progressive leftist ideals of the 1960's and a feeling of alienation compounded by the environment that it grew up in. Richard Hell called this group the Blank Generation, espousing feelings of a disillusioned underclass, an angry youth neglected and negated from a society that he no longer felt a part of, “I was saying let me out of here before I was even born/It’s such a gamble when you get a face.”

Despite being a New Yorker, Hell hit the feelings of the disillusioned British youth remarkable accuracy, combining the nihilism, hopelessness and aesthetics (“It’s such a gamble when you get a face”) that in some ways reflect the punk movement itself. The cultural phenomenon that was to become known as punk exploded in Britain in the mid to late 70's. The relative economic decline of the nation and an increasing feeling of emptiness was reflected in this new, young art form that discovered its roots in a history of youth protest and subculture.

The Blank Generation was primarily based in the urban working class; it grew up in a society where traditional ideas of community were being replaced with the sinister politics of extremism and consumer capitalism, housed in new tower blocks and under the relentless noise of the West Way pass in London. Areas of the Capital such as Croydon epitomised this, its gargantuan concrete structures that were modern and exciting ten or twenty years before were now in terminal decay. As a result the dreams of the sixties could be seen to be in decay. By the mid 70's the modern was little more than a worn out thorough-fare. The architecture of modernity was part of the greater process of alienation and a signifier of the decline that society had created among the urban working class. Vertical rather than horizontal living placed neighbours above rather than opposite, creating a sense of inherent division within the working class that encouraged removal of a sense of collectivism that working class folklore had long articulated. Individualism without opportunity was presented to the urban youth; the possibility of rebellion became a clear option to the Blank Generation.

Forming a band was an obvious way to try and make money; Mark Perry quite emphasised by Alternative TV “I haven’t got any money! That’s why I’m screaming at ya!” What made punk unique as both an artistic and social force was that by its very simplicity it made a form of art available to everyone, one that offered a sense of community (for example by being regularly seen in the Roxy and 100 Clubs), a sense of belonging created from within a perceived environment of alienation. In that way punk was a product of its environment, something unique and also something that was uniquely British.

Perpetual crisis and fear appeared to cast a shadow over Britain throughout the 1970s from the cuts of the three day working week to the IMF crisis in 1976. Parts of the working classes seemed to be locked into a kind of nuclear nihilism, where by the pressures of a de-industrialising economy coincided with a rise in political and terrorist militancy, and a rise in consumerism. Punk was art reflecting society, a melting economy and the seemingly constant threat of industrial action; it was only a country such as Britain that could give rise to the nihilistic populism of punk.

While punk was mirroring the work of the hierarchy of government, it also began affecting it. A Conservative member of the Greater London Council, Bernard Brook-Partridge, commented that “Punk Rock is…nauseating, disgusting, degrading, ghastly, sleazy, prurient, voyeuristic and generally nauseating…I think most of its groups would be vastly improved with sudden death.”

The establishment took a dislike to punk rock’s Nazi imagery and the anti-liberal sloganeering that it created.

This is not the case. Rastifarian DJ Don Letts had a residency at seminal punk club the Roxy, and the Rock against Racism movement is another example of the anti racist nature of punk, as is the March 25, 1978 issue of Sounds magazine, the front cover of which shows various punks, reggae artists and pop stars with ‘Deported’ stamped across their foreheads and the caption ‘Is this the future of rock and roll?’ It was a clear political warning to its predominantly teenage readership. Melody Maker’s Caroline Coon, a key figure in punk, asserts that in the punk scene “There was little or no sexism or racism.”

Punk was undoubtedly a mobilising force of youth, its broad appeal of hopelessness, rebellion and angst was only a surface for its other goals of self destructive nihilism, anti-racism and anti-fascism. It had become central to the understanding of the resurgence of youth politics in recent years. Greil Marcus lavishly described this resurgence as "the multiplication of new voices from below, the intensification of abuse from above, both sides fighting for possession of that suddenly cleared ground."

A vacuum left by both a Labour party tarnished with power and the loss of a sense of community increased the appeal of new cultural/political forces like punk, and it in turn was able to offer a viable alternative.

The most notable of political punk bands were the Clash, who were a virulently left wing and anti-racist group. Lead singer Joe Strummer was always ready to deliver a political diatribe. “We’re anti fascist, we’re anti violence, we’re anti racist and we’re pro-creative, we’re against ignorance” he said. Strummer summarises political punk, in all its idealistic forms, as a subculture that reflects the ills of society and by highlighting them it is redressing them. Punk’s main power base, the Blank Generation, becomes a powerful but concealed metaphor for social change, the compressed image of a society which had crucially changed.

The Blank Generation’s nihilism had been fermented by the collapse of consensus, the rise of extremism had made the idealist, peaceful, youth rebellions of the 1960's appear defunct and anachronistic. The punks had had enough of hippies. Instead of indulging in drugs and women, having intellectual conversations on floor cushions whilst listening to folksy protest songs, the Blank Generation was more angry, disinterested with the seemingly stagnant, peaceful approach of the Hippies, Teenagers screamed philosophy; thugs made poetry; women demystified the female. When Johnny Rotten said “Never trust a fucking hippie,” it wasn’t because he saw them as ageing and futile. It was because they had to many come to represent the plight of rock and roll. It was their rock and roll and it meant nothing to a new disgruntled group of artists. What in the 1950's had been rebellious and riot-inducing (such as the teenage revolt after the first showing of Black Board Jungle in 1955) was now tired, riddled with millionaires, drug addictions and worst of all it had become acceptable

The Hippies were seen by the Blank Generation as part of the very establishment that was alienating them,. The Hippies’ brand of Rock and Roll became the artistic manifestation of everything that was wrong with society. It was bloated, and out of touch. Bands like Pink Floyd and Yes were producing hour-long albums with three or four tracks only, Rock and Roll had lost, as journalist Mick Farren said, “A core of rebellion, sexuality, assertion and even violence.” Another aspect in the mentality of the punk, therefore, was the return to the roots of Rock and Roll, to offer disgruntled youths an outlet for their anger that was aimed towards the establishment and to offer an alternative culture with a gleeful taste for destruction.

Punk grew from the minds of the Blank Generation, surrounded by tenement after tenement and with little job opportunities, due to the rise of youth unemployment, that was in turn helped by an overall decline in unskilled manual labour. Anything that was on offer was seemingly of little interest. The Clash’s track ‘Career Opportunities’ epitomises this “They offered me the office/They offered me the shop/They said I’d better take anything they’d got.” Certain elements of the British youth seemed surrounded by impending doom, growing up in an environment of political and terrorist militancy, with a sense of lost community and little obvious alternatives to failing. These Bored Teenagers went on to form their own subcultural group in order to find their voice and to find a creative outlet for the frustrations of modern life.

Part two Resistance through Style will follow next month.

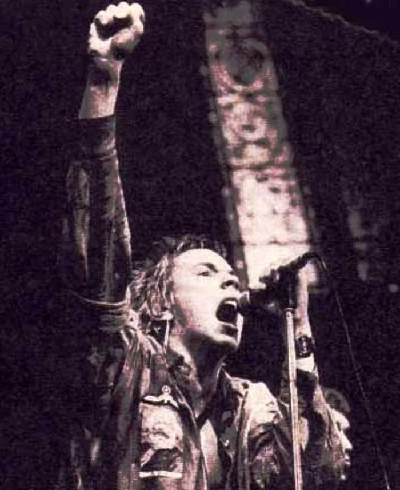

Picture Gallery:-

Visitor Comments:-

|

|

213 Posted By: Nate, Madison, WI, USA on 02 Sep 2009 |

Except for the fact that punk started in the USA, and thus could not be "uniquely British" (as the article itself even seems to admit with its reference to Richard Hell), this article is right on. What would be more accurate would be to say that punk had a unique political significance in Britain that it lacked elsewhere... although it certainly had a strong, though different, political significance in the USA with the onset of the Reagan era.

Part of the uniqueness of British punk is something that you don't quite get at here. You keep mentioning the working class, but fail to mention that Britain maintained a much stricter class division than other countries for far longer. Punk in the USA couldn't be a working class movement in the way it was in the UK for the reason that the US working class is poorly defined and there is no clear demarcation between working class and middle class, whereas people in the UK seem to have a firm idea of what class they belong to, and it seems to be something you inherit from your parents rather than from the career you find yourself in.

|

|

176 Posted By: Michael quigley, Malaysia on 27 Apr 2009 |

omg, this article is like, totally awesome.

i love it.

i love you.

im gay.

fml

|