published: 14 /

10 /

2004

The Sensational Alex Harvey Band were Scotland's biggest musical export in the mid 1970's after the Bay City Rollers. In the first part of a two part interview, both to be run consecutively they talk to John Clarkson about the group's rise

Article

When Alex Harvey died in 1982 a day short of his 47th birthday, his body shutting down on him after years of hard living in Zeebrugge at the end of a month long European tour, his death merited only four paragraphs in 'The Scotsman', and just three in Scotland's other national broadsheet, 'The Herald'.

Rock music in the early 1980's did not generate the column space it does now in the quality newspapers. Harvey was also out of his prime when he suffered the two heart attacks that killed him, the first as he waited with his last band the Electric Cowboys for a boat to take him back to Britain, and the final one in the ambulance as he was taken to hospital. It was nevertheless a particulary under acknowledged death.

Only a few years before in the mid 1970's the flamboyant and always colourful Harvey , along with his group the Sensational Alex Harvey Band, had been,Scotland's biggest musical export after the Bay City Rollers.

Harvey, who was brought up in the infamous Gorbals slums in Glasgow, made his professional debut in 1954 at the age of 19 playing the trumpet at a friend's wedding. He would not, however, meet with real success until over 15 years later and when he was already in his mid 30's.

In 1957 he had an early brief brush with notoriety when he won a competition in 'The Sunday Mail' newspaper to "find Scotland's Tommy Steele." The gallus Harvey in fact had little in common with Steele. He tended to hit his guitar rather than to strum it, and, unlike the chirpy-voiced and easy-on-the-ear Steele, would bawl out his vocals in a bluesy shout. Winning the competition, while providing him with only transient fame, gave him initial exposure, and also allowed him to tour for the first time

In the early 1960's Harvey, his career drifting towards a standstill in Scotland, moved to Hamburg where with his then group the Alex Harvey Soul Band he would, like the young Beatles, often play several sets on the clubs on the Reeperbahn a night, doing covers by the likes of Muddy Waters, Ray Charles and Bo Diddley and also thowing an occasional composition of his own for good measure. The Alex Harvey Soul Band recorded an album, 'Alex Harvey and His Soul Band' (1963) , it made little an impact. When the Soul Band broke up shortly afterwards, Harvey returned to Glasgow, but then eventually moved to London where he joined the musical 'Hair' and spent the next four years playing as a guitarist in its pit band. He recorded another three albums, 'The Blues' (1964), 'Alex Harvey Sings Songs from Hair' (1967) and the more traditional 'Roman Wall Blues' (1969), but again they sold poorly, The early 70's found him playing to diminishing increasingly diiminshing audiences.

In April 1972 Harvey played a gig with Tear Gas, a Glaswegian hard rock act. It was to be a momentous meeting for both parties. Tear Gas had recorded two albums, 'Piggy Go Getter' (1970) and 'Tear Gas' (1971) and had garnished a reputation for being "five times louder and ten times livelier than anyone else." They, like Harvey, were, however, facing dwindling returns and were on the verge of splitting up. Both Harvey and Tear Gas in a last ditch attempt at success decided to throw in their lot together, and, taking up the moniker of the Sensational Alex Harvey Band, began a rigorous schedule of hard touring. It was to pay off.

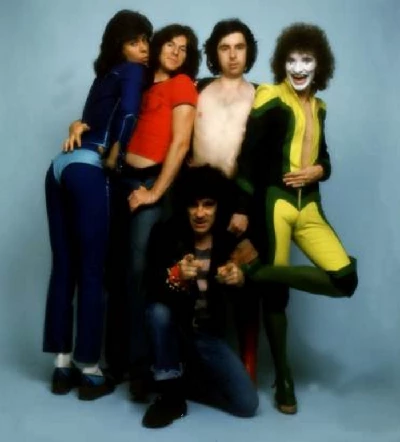

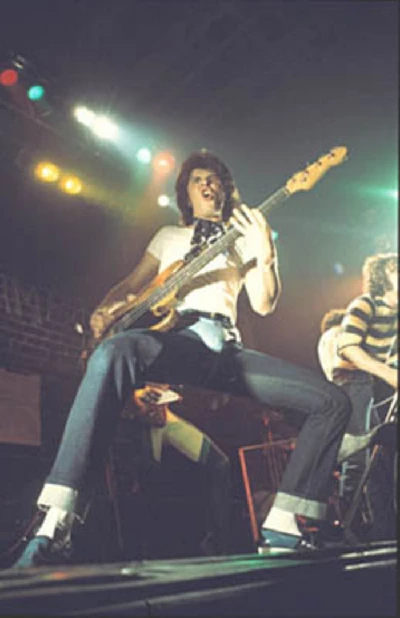

The Sensational Alex Harvey Band (SAHB), which consisted as well as Harvey (vocals) of Zal Cleminson (guitar), Chris Glen (bass), and cousins Ted McKenna (drums) and Hugh McKenna (keyboards ; replaced by Tommy Eyre in 1977), recorded seven studio albums together, 'Framed' (1972), 'Next' (1973), 'The Impossible Dream' (1974), 'Tomorrow Belongs to Me' (1975), 'The Penthouse Tapes' (1976), 'SAHB Stories' (1976) and 'Rock Drill' (1978). Many of these went silver and gold.

While they made no initial indentation on the singles charts, they scored later successes with the rumbustious 'Delilah' (1975), a half-comical, half-sinister cover of a murder ballad that had been originally sung by Tom Jones, and 'Boston Tea Party' (1976), their own dark tribute to the 200th anniversary of the American Declaration of Independence.

It was, however, as a live act that the Sensational Alex Harvey Band made the most impression. During their stage shows they combined music, and their brazen rock riffs, with elements of both street theatre and pantomine. For 'Man in the Jar' Harvey would play the role of a seedy private eye, putting on a grubby overcoat and fedora for the part, and during 'Vambo Marble Eye he would assume the mantle of Vambo, a teenage punk and super hero of the future, and spray paint an imitation brick wall with the slogan 'Vambo Rool.' 'Framed' found him punching his way through the same wall, and sometimes lampooning its lyrics by taking on the role of a bug-eyed Hitler, while 'Delilah' had him dancing with a rubber doll and then throttling it to death.

He was matched in this by the other members of the band. Zal Cleminson, looking like a cross between Marcel Morceau and the Joker, always wore face paint on stage, and twisted his face into exaggerated contortions as he wrestled with his guitar, Chris Glen, usually a favourite amongst SAHB's female fans, meanwhile wore an over-sized, ridiculous-looking, cod piece.

1975 was SAHB's golden year. They headlined the bill at the Reading Festival for the second time and toured America twice. They finished the year in triumphant style by playing seven still fondly remembered shows, four at the London New Victoria and three at the Glasgow Apollo, which found them performing against the backdrop of a massive 'Vambo' set-an eerie, spectacular cross between a set of castle ramparts and a dilipidated tenement-that was specially designed for them by top designer Peter Styples.

In 1976, however, the Sensational Alex Harvey Band's fortunes started to decline. Their manager, Bill Fehilly, was killed in a plane crash, and Harvey began to battle against both poor health and also alcohol problems. They broke up in October 1977 when he walked out four days before the band was due to begin a European tour.

During the last four years of his life, Harvey's luck continued to wane. Still fighting against failing health and alcoholism, he retired briefly from the music business, but returned to touring with both his New Band and also the Electric Cowboys, and also released two sadly little heard solo albums, 'The Mafia Stole my Guitar' (1979) and the posthumous 'The Soldier on the Wall' (1983).

The rest of SAHB have met with mixed fortunes since the band's original demise. Cleminson, Glen and Ted McKenna, at the instigation of their management, briefly formed ZAL with Tubes backing vocalist LeRoy Jones, but feeling that the band was a poor imitation of SAHB, decided to split it up after five months. Both Glen and Ted McKenna then went on to find further success with the Michael Schenker Group. Glen has also worked with John Martyn, while McKenna, much in demand as a session drummer in the 80's, also worked with the late Rory Gallagher and Womack and Womack. Cleminson worked with both Elkie Brooks and Nazareth, but spent most of the 80's out of the music business. Hugh McKenna meanwhile has held down an erratic solo career.

In 1993 the Sensational Alex Harvey reformed for the first tim e with former Zero Zero singer Stevie Doherty on vocals. They then reformed again in 2002 with Billy Rankin, who had played guitar in ZAL, taking on the role of frontman.

In the time since Harvey died, the Sensational Alex Harvey Band's stature has grown again. Bands such as the Cosmic Rough Riders and Muse cite them as an influence. They have been the subject of various television and radio programmes, and there are now two biographies about them. The People's Palace, a local history museum in Glasgow, holds a permanent exhibition of SAHB memorabalia, and the band's critical standing and reputation is now such that Martin Kielty, the new manager of the band, and the author of 'SAHB Story', the most recent of two biographies, was recently able to have Harvey enlisted into the Who's Who Dictionary of National Biography.

Earlier this year the Sensational Alex Harvey Band decided to reform again for what they say is last time with the band's fourth singer, musical and theatrical performer Max Maxwell. While both Doherty and Rankin were straight rock frontmen, Maxwell, who has spent years in bands of all genres and played the role of Ebeneezer Goode on stage with the Shamen in early 90's, plans to reintroduce theatre into the band's stage show. A 12 date UK tour will take place at the end of November and the beginning of December. While the tour is billed as their "farwell tour", 2004 finds the members of SAHB optimistic about and looking forward to the future.

Pennyblackmusic spoke to Chris Glen and Ted McKenna over the course of an evening in late September in a pub in central Glasgow, and then to Zal Cleminson a few weeks later on the phone.

In a long interview, which we are splitting in two parts, both to be run consecutively, they spoke to us about the group's whole 32 year history, beginning with Tear Gas' first meeting with Harvey, and concluded by talking about the forthcoming tour.

PB : Alex Harvey was already a veteran of the Scottish music scene when you first met him, and had been playing gigs and recording music for over 15 years before SAHB got together. How aware were you of his legacy before you met him, and how did you first get together ?

ZC : I saw him when he played the Picasso Club in Glasgow with his Soul Band in the early 60’s and they were phenomenal. They were such a professional-sounding outfit, but because he was of a different generation I didn’t stop to think ‘Right, I need to take this on board’. He wasn’t doing anything there that we didn’t understand. We had been brought up ourselves playing soul music when we first left school, all the Tamlas, and James Browns and that sort of thing .

TM : I was vaguely familiar of the Alex Harvey Soul Band, but that was all. We weren’t experts by any means on his previous scenario.

CG : From my point of view I had just heard of him as a name, but I didn’t know much more than that. Tear Gas played the London Marquee and supported Alex and that was when we first met him.

ZC :He was playing with a three man outift which had him on guitar, and which also featured a bassist and a drummer. It was completely different to what I had seen at the Picasso which had been very much a soul thing, and which was very tight and well organised. What he was doing at the Marquee was much more experimental. It was out-of-tune, and, to be honest, wasn’t that great.

I was less than impressed with it( Laughs). I didn’t even go out of the dressing room to see them.I just sat in the dressing room and listened to it from there,. I thought ‘ Well, fair enough’, but I didn’t think that anything special was about to happen. The rest of it, however, was history so to speak.

TM : After we had played that gig with him our manager told us that Alex was well known amongst his peers and that he had a lot of respect in the business. It carried on from there.

ZC : Even at that stage there were things afoot with the management people. Mountain, who looked after Alex, and the people in Glasgow who worked with us were in contact with each other. I think someone had said ’Let’s put these two together if we possibly can’.

When that was finally put to us, we thought ‘Okay, let’s see what happens.’ We were back in Glasgow, and Alex came up from London where he was living to meet us. We met up in a pub, the Burns Howff, which was in West Regent Street, and sat down and had a drink together.

We had arranged a rehearsal room for later that day and went along and ran through a few tracks. Alex had a bunch of the material that he wanted us to do, so we just hammered the shit out of it and went ‘How does that sound ?’ and fortunately for all of us he was pretty knocked out.

TM : Our main worry was if we could play with him. While I thought that he was charismatic, I wasn’t very impressed with what he was doing and thought that his band were pretty lukewarm. Of course, when we did get together it clicked and there was this big all round sigh of relief.

PB : It has been said that he needed you as much as you needed him. Do you think that that’s true?

ZC : Yeah, I would say that that is absolutely true. What I saw at the Marquee wouldn’t have gone on another five minutes as far as I could see. I didn’t see anything in that which was going to turn people’s heads.

CG : Yeah in hindsight I do believe that. We weren’t as impressed with Alex as he was with us because he saw potential in us that we didn’t initially see in him. What was he saw was a fuck off, in-your-face loud rock band that didn’t give a shit, and he thought ‘That’s what I need’. What we saw was in him was a blues singer from the olden days, but when we started off playing his stuff we thought ‘Wait a minute here. We’re getting offered money to do this’, and then we thought ‘Well, this keeps us together if we play with it, so it’s not too bad’. And then we thought ‘Well, this is quite good. This is good fun.’ And then it grew and grew and grew and just went from there.

PB : Alex chose the title of ‘Sensational’ for the band. It was a name which gave you all a lot to live up to. Did you all feel that you had to be sensational after that ?

CG : No, no, not at all. You have to remember it wasn’t a new band. It was already a band, but with a different singer, and a singer with a ready built band. We were going to call it just the Alex Harvey Band , but then he came up with the title of the Sensational Alex Harvey Band. That was a throwback to the Fabulous Temptations and all those guys.

The first thing we thought was ‘Fuck, you’re asking for a kickin' if you call it that’. As far as Alex was concerned though, it was a good way of getting the interest of the papers. They would think ‘Oh, they think they’re sensational. I’ll just have a fucking listen to this, and then I’ll be able to slag them off.' If you believe in yourself though it is a good thing because then you get the attention of people.

PB : Alex lost his younger brother Leslie just before the Sensational Alex Harvey Band formed. (Leslie Harvey, also a musician, was electrocuted on stage in Swansea while his band Stone the Crows were playing a show-Ed). Leslie’s death seems to have left him very aware of how easy it is for talent to go to waste. He was very driven in the early years of SAHB. Do you think that tragedy contributed to much of his determination to succeed ?

CG : It actually happened at that time just when we were getting together. I don’t think that it made any difference. I think that it was a totally seperate thing. He was just like that anyway.

TM : I never thought that it was part of it either.

ZC : I think it probably did have an effect. I think that it put a chip on his shoulder and that he did carry that concept around with him that the world was robbed of someone who was a great guitar player. There were occasions when he got angry , and you would wonder “Why are you angry, Alex ? and it probably it had a lot to do with that even though he didn’t say anything outright..’You thought ‘Fuck it ! It’s just Alex being Alex again’, but I think in hindsight that a lot of that had to do with Leslie’s death, and the bitterness he had about that. That maybe did come out in his perfomances as well.

CG : Alex was always aware obviously of anything electrical after that. Tam, our head roadie, used to check our equipment just to make sure that you couldn’t even get a static charge of it or anything like that. The only shock that we got on tour was off our hotel keys when they touched the walls in America.

PB : ‘Framed’, SAHB’s first album, was produced by the band. Is it true that it was recorded very, very quickly ?

CG : It was recorded and mixed in three days.

PB : Was there a real sense of urgency to the recording ?

CG : Oh, totally. All the material on that album was all stuff that Alex already had. It was always a case with us of getting one batch of stuff out of the way, getting out on the road with it and then getting the new stuff in.

ZC : We did a lot of pre-rehearsal for ‘Framed’. We knew the songs by heart. It wasn’t a case of us going into the studio and saying ‘Hang on, what are we going to play here ? How do we work this out ?’ It was all done beforehand. We had been gigging a lot, so those songs were in shape. It was just a question of going in and playing them live, which was more or less what we did with hardly any overdubs on them. There is a real raw energy to it. There is a tightness about it. Even now you’ll find that we do probably most of ‘Framed’ live, just about every song. It just shows you the way it holds up. It’s full of good basic rock riffs which people seem to dig.

PB : Alex wasn’t very happy with ‘Framed’ though, was he ?

CG : He was at the time. That was in hindsight. Alex was very positive about the promotion of the album at first. Regardless of the lack of production on the album, the playing does come across as pretty damned good..

TM : I always felt that perhaps it let him down perhaps more than anyone else. The vocals were not as perhaps as prominent on the record as they should have been, although they were improved when the album was remastered. Initially we were all very happy with the contrast in the sound from the last Tear Gas album. We were really happy about the way the band sounded, and the way we played.

PB : The group played one of its first tours in 1973 supporting Slade. Slade’s audiences had a reputation of being notoriously difficult to crack, and were prone to being fairly intolerant and abusive of other bands. You were going out there every night and getting bombarded by coins and missiles. Do you think that experience toughened you up as a group ?

ZC : It wasn’t something which was totally new to us. We had played in front of hostile audiences before, and I am sure Alex had as well. Our attitude was ‘Oh, so you want to give us a bit of stick, do you ? Here have some of this.’ All it did was make us even more determined to wind them up. If they were trying to give us a hard time, then we would move nearer and nearer to the front of the stage, and further and further towards the audience . That was the way Alex approached anything like that. He would basically say ‘Okay, you want to have a go at us. We’re going to stay on longer then, and we’re not going to go off.’

CG : Alex would turn it into a pantomine. They would say ‘Fuck you’, and he would say ‘Fuck you’ and then they would start enjoying themselves. Alex’s attitude always was that a negative reaction is better in some ways than no reaction. By the end of the set they were actually enjoy booing us, and enjoying bantering with us.

Alex had a great trick. All the audience would be talking, and Alex would start talking into the microphone really quietly. Even if you don’t like someone you still turn round in those circumstances to the person next to you and say ‘Shut up ! I can’t hear what he is saying’. The audience would then quieten down.

ZC : Maybe they were curious and thought ‘I’m not really kind of sure about these guys’, but the irony was, of course, that when we went back on tour later by ourselves half the people in the audience were Slade fans.

PB : SAHB always had strong theatrical tendencies. When did you start experimenting with the make-up ?

ZC : It was quite early on. I don’t remember the exact date. When we first got together with Alex and started doing a lot of gigs, Bill Fehilly used to say ‘Look, you’re doing all this visual stuff, but no one in the back of the hall can see what you are doing and nobody can see what is going on.’ That is where it started from.

CG : Eveything started slowly and from small beginnings. It started off with Zal wearing green letraset dots.

TM : Alex was aware of the fact that Zal made a lot of faces when he played and he encouraged him to do something exaggerated, and it went through several changes.. Everything about the stage act, everything in fact, was developing at the same time. It came in bits and spurts.

ZC : We went to see Marcel Marceau in New York, and picked up a lot of stuff from that. We went to see some cabaret in Paris, and got some ideas from there a show called ‘Alcazar’. The face came out of that. It became this trademark thing.

CG : With a lot of bands the personas of the group are manufactured. They want you to look like this. They want you to do this. Everything is geared. Alex’s way of doing things was to take what you already had and to exaggerate it, so you felt comfortable with it. You never felt with him ‘I don’t want to do this.’

PB : He had been in ‘Hair’, hadn’t he ? Do you think that had had an effect ?

CG : Oh yes, definitely from a presentation point.

TM : He told me that he watched how the American producers came in and how they guided the show and how they would always look for a focal point. That’s basically what he introduced into the band. No matter what’s going on with the audience you have to tell the audience what to look for. That’s the key to any production

CG : Hence we did a little dance in ‘Delilah’ and before that we did “Runaway’ and used to do a little dance in that. It was just a feature. You wanted maybe four parts in light relief in any show that would give the audience something to focus on.

PB : You became successful pretty quickly under the Sensational Alex Harvey Band moniker.

TM : We went out and worked all the time. We went out and played everywhere we could-pubs, clubs, colleges, schools, prisons.

CG : Back then you had artist development, but nowadays that never happens. We were signed to a three album deal by Phonogram. Your singles then weren’t made to go into the charts. They were turntable hits. As long as you got played on the radio, people then would hear your name and then they would go and see a gig. Nowadays a band doesn’t do a gig unless it has had a hit record, and you don’t make an album unless you have had two hit singles.

When ‘Next’ went silver and then went gold, and at the same time ‘”Framed’ went silver, you still couldn’t get arrested with one of our singles.

TM : Although it seemed to come quite quickly we basically saturated our grass roots. We would go and play a place, and then we would go back and play that place again, and there would eventually be queues outside the door, because we focused so aggresively on our live following.

ZC : Things became meteoric in some places. You would go to some places, and there were 50 people there the week before and now there was 300.

TM : We went down a storm. We started selling halls out, while bands that were at number one in the charts struggled to sell half the tickets at the same venues.

CG : We did Newcastle City Hall on one tour, and it had sold out in one day. I remember asking the woman who was promoting it, and who was in charge of the ticket sales who else was playing there that week, and that band Pilot were playing. They had had two number one singles with ‘January’ and ‘Magic’. Sweet had also recently played there. I asked what kind of crowds they got, and you couldn’t get fucking arrested with a ticket for their gig. The place was half full, and both these bands had had number ones. We sold out, and we hadn’t even had a record in the charts at that stage.

TM : It was a fabulous tme. That whole experience of just believing in it and watching it grow was incredible. We played the Reading Festival for the first time n 1973 and opened up with ‘Faith Healer’ at the bottom of the bill. That was the point when I think we all felt that this was all really happening, and we really had something.

PB : ‘Next’has a track called ‘Gang Bang’ on it, which was a very politically incorrect choice for a name of a song even in those days.SAHB , however, seemed to be a band that noone seemed to take offence at, however outrageous or controversial they were.

ZC : It is a song I have felt quite ambivalent about over the years. I know that some of the guys in the band are not too sure about the politically correct aspect of it either, but the funny thing about that is the song goes down as well with women as it does the men. Nobody is going to be that prudish if you’re playing to a rock audience. If you were going to try and do that on TV, and maybe ‘Top of the Pops’ that might be a little different.

PB : There were serious messages sometimes underneath, but you always managed to be fun. Do you think as well that everyone realised that something like that was firmly tongue-in-cheek ?

ZC : Yeah, that was one of the saving graces with the band sometimes. People used to find Alex quite intimidating, and the band could look quite intimidating, and then at the same time everything would suddenly be blown apart by some sort of tongue-in-cheek thing that we would do, and everybody would fall about laughing and be left thinking ‘Wow, what was that all about ?’ One minute you’rte getting this heavy duty in-your-face kind of thing, and then the next minute there’s this kind of pantomine thing going on. That became, if you like, the band’s trademark.

PB : ‘The Impossible Dream’, your third album, was described by the rock journalist Charles Shaar Murray, who was one of your big fans, as ‘a rock ‘n’ roll comic book”. Would you agree with that ?

CG : Yes. It followed on from ‘Framed’ which was all Alex’s stuff, and “Next’, which was very heavily produced by Phil Wainman. While ’Next’ was a good album, we felt very constrained during the making of it because Phil wanted to put his stamp on it, On ‘The Impossible Dream’ the bubble burst. Everything came out at once and in all different directions. It was the first time that we felt that the arrangements were really ours.

TM : It all went hand in hand with the fact that we were all developing an identity as far as our stage persona was concerned. The gel or the flavour of the band was also becoming more bizarre and extreme. We started off by being like a heavy rock band, but then we couldn’t take that seriously. We thought that it was too funny.

CG : And like Spinal Tap .

TM : We used to laugh at the whole idea and concept of guys getting up on stage. It didn’t make any sense, so when Alex suggested doing something like a tango we would say “Yeah, that makes sense.” The key factor to the whole thing was we started to believe that we could do anything if we believed in it. We felt that if we could get into a song we could take the audience with us.

PB : Alex and Hugh shared most of the songwriting credits. How much impact did the rest of you have in creating the songs ?

CG : That would be the beginning of a very long conversation if you wanted to break it down to talk about individual songs. Things, however,usually expanded from the person who had the original idea, and the credit of the original song. If you heard, for example, the original version of ‘Faith Healer’ with piano and vocals, compared with what went down on record, they’re not nearly the same. From ‘The Impossible Dream’ onwards that became much more pronounced.

PB : You headlined Reading in both 1974 and then again in 1975. Did you feel then in those years that you would perhaps go on forever ?

ZC : Yeah,definitely. Everything was very healthy and Alex was very healthy. You go on every night and blow people away, and you think ‘Oh well, this is what I’ll do for the rest of my llife.’ You feel that you’re indestructible. We felt that Alex was indestructible, but the reality was he was anything but.

CG : Everything was very insular though for us as well . Unlike a lot of bands now who only do festivals, and have lots of time off, we had no time off. I thought we were quite good, but we never really interacted much with other musicians. Only when the band split did we find out we were fucking good, because other people wanted us to play with them. It was then that we found out that other musicians really respected us. Before then it was very incesteous between us all. We were in each other’s company all the time.

PB : You finished off 1975 by playing the Christmas shows at the London New Victoria and at the Glasgow Apollo. Even now 30 years on those shows are still remembered fondly. Why were those shows never filmed ?

TM : It was just a lack of vision on behalf of the management. It was all happening then. If someone had filmed those, that would have been our piece de resistance.

CG : We were out with the timing. It was in the days just before video.

PB : SAHB would have been the ultimate video band , woudn't they ?

CG : It’s true. It t would have been great if there had been video then .

TM : The best reaction we ever got was when people saw an ‘In Concert’ film we did at the London Rainbow for the BBC . Loads of people said that they saw that in America. The reaction was incredible. We were definitely pre-video. We were made for video the way we see it now, just for our live performances alone.

Picture Gallery:-

Visitor Comments:-

|

|

899 Posted By: James Anderson, Camden Arkansas on 27 Oct 2019 |

Thanks for the great interview. I saw SAHB 2 nights at the Roxy (or the Whiskey A Go-Go) when I was in high school. They were Sensational!!!

|