published: 7 /

1 /

2023

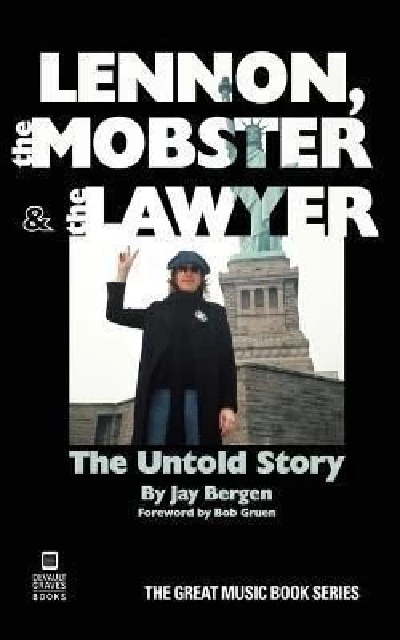

Lisa Torem speaks to Jay Bergen about his ‘under-the-radar’ memoir, ‘Lennon, Mobster and The Lawyer’, which is a fascinating account of John Lennon’s commitment to the courtroom when battling two lawsuits, with Bergen as his attorney.

Article

I had the pleasure of meeting attorney/author Jay Bergen as he signed books at a Chicago-land Fest For Beatles in mid-August 2022. The books flew off his table and into the hands of eager Beatles fans as he warmly greeted those in the front of the line. Later on, he conveyed his back story to an interviewer at the main stage in front of rapt fans.

Why was the demand for his product so high? A quick glance at the fine print answered the question. His memoir involved John Lennon and a court case in which the former Beatle had been subjected to bullying by a record label owner with a questionable past. Bergen had been Lennon’s attorney.

But Bergen’s journey with Lennon was more than a court battle over rights that he and Lennon efficiently won. For this interview with Pennyblackmusic, Bergen talks about the emotional after effects of working professionally with Lennon and how that experience affected his own outlook for years afterwards.

PB: Good morning, Jay. What motivated you to write ‘Lennon Mobster & The Lawyer’ at this specific point in time?

JB: I’d been carrying around five or six banker’s boxes with the entire original trial transcript of the testimony and also the record of the appeal, so I had ten-thousand pages of testimony, exhibits, including Beatles albums, and I had moved them between four or five moves.

Finally, in May of 2017, I was trying to figure out what to do with them; maybe donate them to the Rock ‘n’ Roll Hall of Fame.

I went out to the garage where I had them stored and I sat down and started to read John’s testimony. I thought, There’s a story here. There’s a story that hasn’t been told because this case flew under the radar--John had just dropped out of the music business. I really wanted to tell the story for two reasons:

First of all, I’d met John Lennon before, but this was a different John Lennon. He was happy. He was back with Yoko. She was pregnant. He was determined not to give in to Morris Levy. He had handled the ‘Come Together’ settlement and he was really very into the case and in helping me. So the two of us worked together on the case.

The other reason was that some of his testimony was, unlike anything he’d said in public before, about how he made records. He’d done hundreds and hundreds of interviews but he never got into that amount of detail and John and I decided, when we had this judge, Griesa, who was a classical musician, that we were going to teach him how John made records and how The Beatles gradually took control of the whole process.

Why did I hang on to these files? I don’t have files from any other cases that I’ve worked on except for the Major League cases that I’ve worked on for salary arbitrations. I have a handful of documents. So that was it. I started to do research and five years later it was published.

PB: As you said, you had at your disposal a great deal of source material, including testimony and even out-of-courtroom conversations. How did you narrow down the content?

JB: I told the story chronologically and I knew that there was certain testimony that was unneeded. I also worked with a woman named Lorraine Ash, who became my editor. She is an expert on memoirs and she teaches classes on memoir writing.

I met her through an old friend from my Morristown, New Jersey days. She had written a memoir about her grandmother, who she never knew, who died in Auschwitz. Barbara Gilford had put me in touch with Lorraine. I started working with Lorraine in the middle of 2019. She was a big help.

But when we got to the point of talking to a publisher, we had too many words-92,000 words. I cut it to 82. Lorraine cut it to 72. The editor suggested that we cut out four chapters that really cut into the flow of the story. So that’s the way that we narrowed it down.

PB: Morris Levy’s dealings with Lennon also involved a lawsuit concerning ‘You Can’t Catch Me’ from Levy’s catalogue which had been written by Chuck Berry. Allegations were made that Lennon used phrases from the song in ‘Come Together.’ How did the subsequent lawsuit come about?

JB I wasn’t involved in that. That case started in 1970. My partner, David Dolgenos, got hired to represent John, mainly in connection to the dissolution of The Beatles in 1973 when Lennon left attorney Allen Klein. That case was settled in October of 1973 by John agreeing to record three songs owned by Morris Levy in one of his publishing companies, Big Seven.

That was because the case, instead of just languishing for over three years, was about to go to trial and John had just started working in October of 1973 with Phil Spector in Los Angeles about doing an album of oldies. That was John’s idea. He wanted to do that because he wanted to sing songs written by somebody other than himself or The Beatles, and also these were all very influential songs that he grew up listening to as a teenager. So I didn’t get involved until February of 1975 when these rumors started about Morris Levy putting out a bootleg version of the album.

I had done a couple of small litigation matters for John in connection with some minor things. I’d never met him but I told David that I’d heard rumors around the office, that the law firm, Marshall, Bratter, Green, Allison & Tucker had been linked to litigation involving this Morris Levy and the bootleg album. I went to David and said that I’d like to be involved.

When I joined Marshall, Bradder, Green, Allison & Tucker In the fall of 1972, the first thing that was handed to me was representing Terry Knight in a lawsuit between Terry and Grand Funk Railroad. I had worked on that case for well over a year and a half. I finally settled it very successfully to Terry. So I had a reputation in the office and David called me down and asked me to go to this meeting on February 3rd at Capitol Records. This was the meeting where John Lennon opened the door and came in.

Harold Seider was John’s business advisor and a lawyer who had worked with Allen Klein and now was working with Universal Records in music publishing in Los Angeles. He knew that John needed a lawyer in New York, and through another contract, that’s how he got to my partner. David Dolgenos, So at the time he’d been doing the album, even though I believe Harold offered Lennon a settlement for some money, Levy said he wanted John to sing three songs on what was supposed to be the next album, the ‘Rock and Roll’ album. That’s how that happened. These three songs, since Morris’s company owned all of these rock and roll songs, that was a perfect fit and I think Morris turned down any cash money because, I think, it was his way of getting his hooks into John by having an obligation by John to record three of his songs on this next album.

The problem was that Phil Spector disappeared with the master tapes at the end of 1973. They couldn’t get them back. John then produced an album by Harry Nilsson. He was kind of bored so he was writing songs and decided in the summer of ’74; he really kind of gave up on ever getting the tapes back from Phil.

There was one story where Capitol had it all set up where they were going to pay Phil ninety--thousand dollars and he was going to turn over the tapes. But on that day, Phil refused to come out—he had this big chateau in Los Angeles. He refused to come out of his chateau with the tapes--there were about twenty-eight boxes, because he claimed there were C.I.A. helicopters circling over his head.

John went ahead and did ‘Walls and Bridges,’ his material. When that came out in September of 1974, Levy called and said, ‘Hey, where are my songs? That’s the next album.’ He knew that wasn’t the next album because the next album that came out was ‘Walls and Bridges’ with all of John’s songs. But Capitol got the master tapes back from Phil right around the time that John was ready to start the ‘Walls and Bridges’ album.

He started listening to some of the tracks and realized that, out of the Spector recordings, he had a lot of work to do. So he kind of put them aside and did the ‘Wall and Bridges’ album and he was going to go back to the ‘Rock and Roll’ album after that came out. That’s when Levy said, I want to meet John Lennon and I want to hear the story from him. That was kind of the origin of the contact with Levy because at that meeting, which I explained in the book.

One of the things I learned about John Lennon was that he was very shy and he didn’t like to tell people, no. He got very uncomfortable when people asked him to do things. So he was nervous about this meeting with Morris Levy. He didn’t know who he was. He just wanted to go and explain it and apologize for the things he said during the course of the meeting.

One of the things he said during the meeting at Club Cavallaro was that he was thinking of putting this out on TV. I’m worried that the critics are going to be lying in wait for this album and because of all the negative publicity; all the drinking and the drugging in Los Angeles, when he was there, his ‘lost weekend.’

Secondly, here’s John Lennon trying to interpret classic rock and roll songs from the 1950s and 1960s. As soon as he mentioned TV, Levy said, I’ve got a company that sells albums on TV. Both Seider and John repeated to Levy, I’m tied to EMI and need their permission to do that.

Everybody in the music industry, including Morris, knew that The Beatles, individually, and as a group, were tied up to EMI at that time.

PB: Lennon was reluctant to say no and even spent time with Levy at Disney Land and at Levy’s upstate New York Farm. Did that send up any red flags?

JB: As far as going to the farm, May Pang testified at the meeting at the Club Cavallaro that Morris kept asking John to come to the farm and John kept coming up with excuses. ‘I’m going to Montauk with my friend Mick Jagger.’ Morris would say, ‘Come next week.’

May went to the ladies room and when she came back, John said, ‘We’re going to the farm.’ She asked what happened and he said that he ran out of excuses.

As for Disney Land, it really illustrates how naïve he was. Here he turns over to Morris Levy, the two reels of the entire album and when he tells Seider what he did, Seider says, ‘I wish you hadn’t done that.’

And as for Disney Land, Julian was coming and he was thinking, what am I going to do with my son for two weeks? And there’s a way to do it. When I interviewed Klaus Voormann about John, he said that John was naïve about business. That was a very difficult thing for us to deal with. Why was he hanging out with Morris if there wasn’t some kind of a deal?

PB: You were aware that Morris Levy had unsavory connections. Were you nervous about your personal safety or that of John Lennon at any point?

JB: No, John wasn’t either. We never got into that. We never sat down and talked about that. I don’t know how much he knew about Morris. Of course, I’d heard a lot more as we went along. But I was really confident that Morris was not going to put any strong arm; monkey business. I think, Morris always thought, until we really got into the cases, that he’d be able to wrangle some kind of a deal with John, Capitol and EMI.

In the two lawsuits that he filed, he made these ridiculous allegations about conspiracy, among the three of them, but I think, he was always hoping that there was going to be some kind of a deal done.

One of the things that I quote in the book, on January 30, 1975, when Seider went up to his office to explain to them that Capitol wanted to put this record out, and getting a lot of people in the industry angry, like mom and pop record stores and big chains. He’d start selling it on TV. Morris, you remember the way I described him. When Seider walked in, Morris turned around and started a tape recorder and there’s Harold listening to John singing, ‘You Can’t Catch Me.’

And he said to Seider, ‘I’m going to put it out. I’ve got a shot.’

Morris was a grifter. He’s always got some scam and never does things the legal way. Tommy James wrote a book about his experiences.

PB: That was scary.

JB: Yes, there were points that were scary where Morris called an accountant that Tommy had asked to get in touch with Morris and Morris said, don’t ever call me again or else.

PB: John Lennon agreed to prepare for the case and appear as a witness, yet he frequently reminded you that he was a musician who didn’t discuss business. Can you talk about the process involved in preparing him to speak in a court of law?

JB: He did not like business. I don’t think he liked lawyers, or accountants, or all of the stuff that went with business. Yet we were able to connect almost right from the onset. He found out during the course of our meetings that I loved rock and roll music. I started listening to it at the same time that he started listening to it in England when I was in high school in the early 1950s.

I explained right from the beginning that in my litigation experience, I’m all about the facts. I don’t worry about the law. The law is what the law is, but the facts are the key to every case and I want to get the facts down clearly.

A couple of days after that first meeting, when I went back to Capitol with my first meeting with John and May Pang, I went over the facts and I think that John realized, because I kept harping at him about how important the facts were, that we had a story to tell and the story never changed.

May Pang’s deposition was taken, John’s deposition was taken, Harold Seider’s deposition was taken; the story was always the same. John and I spent a lot of time going over the facts of his deposition which was in May of 1975, and before he testified. And by the time he testified at the trial in January of 1976, we really had the facts locked in.

They were very clean and I remember telling John one day, ‘We’re really in good shape on the facts’ and Levy is not going to be. John asked, ‘Why’s that?’ I said it’s because Levy has to lie. He has to tell a different story and as it turned out, Levy never got the facts right. He was a terrible witness. His lawyer had not prepared him and we were prepared. John was ready and eager. He and Yoko came every day to the trial even on days when he didn’t have to testify. He realized right from the beginning that he had a point to make. He was going to make it by being there.

I was way out in New Jersey so I checked into a hotel a couple of days before the trials. I said, be there and if anything comes up, call me. He called me at midnight the night before the trial and he said, ‘Can Yoko come?’ I said, of course.

They showed up the next day. They were both there. Sean was about three months old then. He’d been born in October of 1975. Yoko never interfered, never said, we should do this or we should do that. Why aren’t we doing this?

She was just there and it was great. They were both there. There was a sequence which I quoted in the book, where a witness from Capitol was testifying and John said something from the spectator section.

To give you an idea of how much confidence I had in him testifying, John said, ‘They’re all rock.’ I looked around. This had never happened before. My client was speaking up from the spectator section. Because we didn’t have a jury, you know, you’re just dealing with the judge, who is going to decide the case.

A couple of minutes later, I said, ‘Can we bring Mr. Lennon on to the stand? ‘The judge said, ‘Oh, yes, of course.’ John walked up and the first thing he said was, ‘Are we still under oath?’

Another thing was that John was used to being questioned in interviews. We’ve all heard some of their interviews where they’re very quick; the four of them; very sharp. He was just a great witness.

PB: The judge spent a great deal of time asking John Lennon about rock music and recording studio practices. He clearly wanted to set the record straight but also seemed genuinely interested in the subject matter. Were you surprised at his line of questioning?

JB: No. The first time we met with judge Griesa in the robing room the afternoon when we had that blowup, with the first judge walking off the bench and recusing himself, he said, ‘Look, I don’t know anything about The Beatles, John Lennon or this case.’ He hadn’t been involved at all; this was brand new to him.

So when we got into the trial, there were several times when he said to us, ‘I listen to a lot of music but I don’t know anything about this music. So if you want me to understand the rock and roll music, you’re going to have to explain it.’ We didn’t have a jury.

We knew before we went into the courtroom with him that he’d only been on the bench for four or five years and we knew that he asked a lot of questions. Some judges would have said, ‘Why don’t you just keep the case going?’ like the first judge; we were almost in a race. I knew Judge McMann, and I knew his reputation but Judge Griesa asked a lot of questions and of course that prolonged the trial.

He was really fascinated. He went into the avant garde albums that John and Yoko had put out; he wanted to know what that was all about. He talked about John Cage and other experimental musicians. He was very very curious.

PB: You wrote that your professional and personal dealings with John Lennon ultimately transformed you. Can you elaborate?

JB: I had gotten away from rock and roll music and then when I got into the case, I saw that John had really stood his ground. At the time of the case, and afterward, I was in a very troubled marriage. I had not stood up for myself, when dealing with my wife at the time. The more I stood up, it became obvious that the marriage was not going to work. I had two young daughters and I finally decided that I had to stand my ground, like John had.

Ultimately, I moved out of the house and got a divorce. The other thing that she didn’t like was, after the case was over, I started to develop a rock and roll practice and she did not like that. She didn’t like the music. She didn’t like the people. She got the idea that I was going to be some kind of drug addict. That was never true. It was just that I loved this music and I tried to develop a practice and was mildly successful but after four or five years of doing that, and still doing my litigation, I decided—the competition in New York, as you can imagine, was fierce, among the lawyers that were steeped in that practice, and also riddled with conflicts.

It was not unusual for a lawyer named Allen Grubman representing CBS Records to also be representing Bruce Springsteen, who was on CBS. So that was something that kind of got in the way. I had some fun for about four or five years and then went back to the litigation.

PB: Your trial work with John Lennon prompted you to take on additional musically-oriented clients. Given your experience with intellectual property rights, etc., can you share some tips that aspiring artists should keep in mind when forging a career and negotiating contracts?

JB: Yes. Do not give away or sell your music publishing. You’ve got to hang on to it. The number of artists that have been screwed by a manager or an agent or a record company—the record companies want to get control of the actual music

When I represented Albert Grossman in litigation against Bob Dylan, in I think, 1978 or 1979, when Albert signed Bob as a manager, he thought he was getting fifty percent of the publishing. Finally, after they were separating after so many years, they did a deal where Albert would continue to get paid over the years with some percentage. And Bob was represented by a accounting firm, who advised him, don’t pay him.

I got hired to handle the lawsuit and after a couple of years of the case going along, we decided that the case was not moving fast enough, and he replaced me with a lawyer, I think, from Los Angeles. I don’t know what happened after that but look at what Bruce Springsteen sold just earlier this year. All of his music publishing and all of his records for Five hundred and fifty million dollars. The same thing happened with David Bowie, Stevie Nicks, Dylan.

I don’t think Stevie Nicks sold everything. I think she sold a portion of it but she was paid Eighty million dollars. And the thing about the music publishing is, all you need is an accountant to collect the royalties.

So I told young artists that I represented; we fought tooth and nail to hang on to the music publishing because it just continues to generate income over the years. You don’t have to do anything except to keep track of it. ASCAP and BMI keep track of the records being played; cover songs. I think that’s probably the most important thing.

The other thing is before you get involved with a manager or an agent, you have to have a lawyer. Dylan, and other artists, have testified… I was about to go on stage and Albert handed me this agreement and said, ‘Sign.’ That’s probably not the way it happens but it’s probably not very far from it because Dylan, or some of these other artists, didn’t have lawyers.

Tom Petty was in a situation where the fellow that was producing his first couple of albums, hadn’t locked up in terms of publishing and then Tom got a lawyer who recommended that he declare bankruptcy because he owed so much money to the record company from the production of his first two albums that he was broke. That enabled him to get out of the contract.

The key thing is, don’t sign anything until you have a lawyer, a lawyer who you can trust.

PB: Aside from promoting the book, you did multi-media presentations in North Carolina, South Carolina and New York. How did the audience respond?

JB: Early on when I started working on the book, I had a friend who is a director and playwright. She, Catherine Gillette, suggested that we do a multi-media show, where we’d write a script and add photos and videos, things like that; background.

Before I knew it, she, and a friend, who was, and still is the executive director of Tryon Fine Arts Center, decided to put on a show there. We wound up doing three nights. It was a small stage and so only seventy people attended. It was only supposed to be one night. They were only charging five dollars admission. It sold out within a couple of days.

After it was over, the executive director said, ‘Will you do it again on Thursday night?’ I said sure. So we sold out again. At this point, she was really upset that she wasn’t charging twenty dollars.

We wound up doing it Tuesday, Thursday and Saturday. And DiAnne and I had gotten involved in the Peace Center for the Performing Arts in Greenville, about thirty or forty miles south of us. We donated money to underserved children so they could have more exposure to the arts. A couple of the young people came to one of the shows and they told the president of the Peace Center, Megan Riegel about it. It has a 2100 seat concert hall. It was spectacular.

A couple of months ago. We saw Steve Martin and Martin Short on their tour there. But there was also a 450-seat theater attached to it where they would show other things.

So I approached Megan about doing the show there. We did it. We sold out. We didn’t make any money from it but I had a videographer shoot the video. The response was just terrific.

We only had ninety minutes and could only tell a portion of the story. We really didn’t get into a lot of the court testimony and that went to the 92nd Street Y. It’s a cultural spot where they have a lot of political talks and artists come in. So we sold out two nights there. One hundred people each and that was in early 2019 and we had a very very positive response.

I had the video transferred just before we went to Chicago to a DVD and I showed it Friday night at the Festival in one of the smaller venues where the merchandising was and the response again was terrific.

PB: What are some of your favorite John Lennon songs?

JB: I always liked ‘Help,’ John’s song, but Paul wrote part of it. It really demonstrated that very early in The Beatles career, he was feeling overwhelmed. I think back and they were in this horserace that just kept going for years and years and was one of the things which led him to drop out of the music business from February of 1975 to August of 1980 when he and Yoko started recording ‘Double Fantasy.’ Look at those lyrics. The other one I really love is ‘Number Nine Dream’ from ‘Walls and Bridges.’

Given all the time I spent with John, I never asked him about The Beatles. I never said, ‘What was it like?’ I think that was another thing that helped us have a good working and pleasant relationship. I didn’t ask him for an autograph. I didn’t ask him for gossip. You read the book. There wasn’t any gossip in it. That’s not why we were together. We were focusing on this case and I think the fact that even though I was a big Beatles fan and was initially shocked when he walked into the room, I treated him like any other client. We were friends, but were we close friends? Did we hang out or anything? No. And I think he appreciated that.

We never talked about it but I didn’t treat him like he was the rock star and I was the fan. That’s probably the best way to put it.

When we got into the limo on the first day of the trial, I said to John, ‘What do you want to eat?’ He said, ‘We’re only eating fish.’ I had a feeling that Yoko had a lot to do with that. I also told the story in the book about the time they showed up in my office with this quart jar. It turned out to have garlic juice in it.

I said, ‘What’s in the jar?’ He said, ‘Garlic juice. Yoko has found out that it’s very healthy." I asked him if I could smell it and luckily he didn’t ask me if I wanted a sip. In the courtroom, we were in a big courtroom for a few days when they had the garlic juice with them. They were drinking the garlic juice back in the room.

So when they said, ‘We’re only eating fish,’ I said, ‘We’re not very far from the old Fulton Fish Market which is along the East River." I knew there were some really classic seafood restaurants there, in terms of what they looked like, but the food…

We pulled up to Sloppy Louie’s; no white tablecloths or anything, just the basics. It was kind of just assumed that we would go back there the next day and the next and the next and then every day. We had fish.

Did you take a look at the tie that John is holding? He’s holding it up. It was a butterfly caught in a spider’s web. I told that story about how they went back there by themselves for years after the trial.

John loved New York. He loved the fact that most of the time people would leave him alone. The whole time we ate at Sloppy Louie’s, I think there was one person that came up and asked him for an autograph and it was a very popular restaurant with the Wall Street business types because we weren’t very far from Wall Street. He was very polite to people. ‘Not while I’m eating,’ that was his one rule for autographs.

PB: Thank you.

Thank you to Christopher Torem

Band Links:-

https://www.lennonthemobsterandthelawy

https://twitter.com/thelennonlawyer

Play in YouTube:-

Picture Gallery:-