published: 30 /

9 /

2016

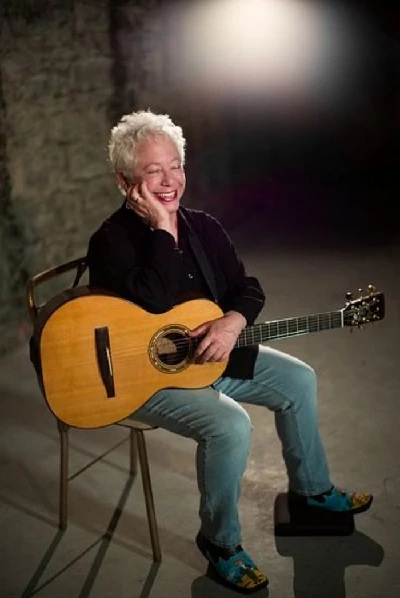

Lisa Torem interviews Janis Ian about the highlights of her five-plus decade career as a singer-songwriter, author and narrator

Article

Janis Ian demonstrated an early love for popular music, and, during her formative years, she learned to play the French horn, harmonica, guitar and organ. Very early in her career, she released ‘Society’s Child’ (‘Baby, I’ve Been Thinking’), which was produced by George “Shadow” Morton. The folk ballad was about a doomed inter-racial relationship. Reaction was initially violent due to severe racial tensions in the US. A radio station was burned down and Ian faced death threats.

“I was singing for people who wanted me dead. I was fifteen years old,” she wrote in her autobiography, 'Society’s Child' (Tarcher/Penguin, 2008), in which she also recounted more than fifty years of personal and professional experiences, and for which she was awarded 2013’s Best Spoken Word Album Grammy for the audio version.

Acoustic samba, ‘At Seventeen’ (‘Between The Lines’, 1975) relays the story of a lonely “ugly duckling girl like me”. One especially heartfelt line, “the valentines I never knew,” prompted fans to then send her hundreds of belated valentines. She came away with a Grammy for Best Pop Vocal Performance that year. In 1979, the single ‘Fly Too High’, produced by Giorgio Moroder, was included in the soundtrack for the film, 'Foxes'. The compelling dance number quickly became an international hit.

Never one to duck tough topics, the New York-born but now Nashville-based Ian would use her poetic talent throughout her career to draw attention to additional social issues and related heartbreaking events. She wrote ‘Matthew’ about a young gay man that was murdered in 1998 in a hate crime and, earlier in that decade, ‘His Hands’ about domestic violence (‘Breaking Silence', 1993).

Dedicating herself to philanthropy in honour of her late mother, Pearl, the singer/songwriter/author established the Pearl Foundation, which enables impoverished women to attend college free of charge. To raise funds, she offers fans opportunities to be “Roadie-of-the-day” or to purchase musical instruments, sheet music and other personal artifacts from Ian’s archives. To date, the foundation has raised over $900,000 dollars.

She cites Billie Holiday, Odetta and Joan Baez as early influences, but she went on to produce more than twenty studio albums of her own. Sony Music has recently announced that Janis Ian will be part of their prestigious Legacy Label in which they will reissue fifteen of her most beloved albums.

Her own vast catalogue of music has been covered by hundreds of vocalists, including Cher, Nina Simone, Roberta Flack, John Mellencamp and Dolly Parton. But besides being known as one of the most influential American songwriters of the 1960s-1970s and beyond, Ian also writes science fiction stories and narrates fiction and non-fiction books for adults and children worldwide.

This is my third Pennyblackmusic interview with Janis Ian, yet it feels like the first. She’s engaging and informative, just as prone to spontaneous laughter as she is to dishing out valuable advice that may steer the course of an emerging artist into a truly magical direction.

I fire away my queries on a sunny afternoon and hope they’re not identical to the ones Janis has just answered. There’s a slight melody and an earned resilience in her candid responses. She’s a songwriter’s songwriter, so professional and knowledgeable, yet so easy to speak with, that I’m afraid I’ll lose track of time.

But legends like Janis Ian? Do they ever lose track of time? We expect them to keep time, but then, when we least expect it, they actually transcend time. A verse in Janis Ian’s ‘Days Like These’ helps address the point.

“In lives like these, where every moment counts/I add up all the things that I can live without/When the one thing left is the blessing of my dreams, I can make my peace with days like these."

Pennyblackmusic welcomes back Janis Ian…

PB: Congratulations on the Sony Legacy news.

JI: Thank you. I thought it was a good move.

PB: I was wondering about the timing. Some artists might respond by saying, “What took you so long?” and others might react by saying, “Wait a minute. I still have so much more to contribute.” How was the timing for you on this?

JI: We’ve actually been in negotiations for two and a half years so if either sides lawyers had been inclined to work a little faster it would have been two-and-a half years ago. We probably could have done the whole thing in a month, so that’s part of the timing issue.

I think for somebody like me who is carrying around so much baggage - I think I own twenty-two albums and I have just released fifteen of them to Sony, a move like this insures that my co-writers get paid, that the publishers get paid, that the recordings get distribution that I can’t afford to keep on top of, so it’s a means to an end. Otherwise I spend all of my time being a record company and publisher and none of it being a creator.

PB: You were one of the early proponents of the digitalized format and that’s now the norm.

JI: I certainly was not one of the first proponents of streaming though. That’s a hard one now. Streaming is paying so little. I had lunch the other day with a friend I was writing with and over lunch we were talking about streaming. He said he just got a note with a check — he had a million-and-a half streams on a hit song and he got a check for a hundred dollars. So that’s really hurting us.

PB: I selected one of those fifteen albums, ‘Night Rains’ (1979) for some further discussion. On it, you had participated in some interesting collaborations. You worked on ‘The Other Side of the Sun’ with Albert Hammond and ‘Jenny’ with Chick Corea. You had said then, that for the first time, “I was recording the music I heard in my head.” Was ‘Night Rains’ a turning point in your career?

JI: Because I was starting to work with other artists?

PB: Yes, but also because you were working as a co-producer.

JI: Co-producer, co-writer, more ensemble work?

PB: Yes.

JI: Well, it was obviously a big turning point when I started working with Albert, because I’d never done any co-writing and he made it completely painless. I learned from him how to be with a new co-writer, and. because my first experience was so good, I went to the next and the next and the next experiences with just the best expectations.

PB: And what were a few of the key things you learned from that first collaboration?

JI: It’s interesting because I wrote a couple of years ago with Bette Midler and it was her first co-write, and then I wrote three weeks ago with Sarah Partridge, who is doing a tribute album to me and we wanted to see whether we couldn’t come up with something together too. And in both instances I was working with artists who have never co-written, and in Bette’s case had never written, and so I always start off with the basic rules.

The first one is, I don’t care whether we get a song or not. That’s really important to tell people because they are desperately worried about that. What if I’m stupid? What if I look like a fool? What if I’m not having a good day? All of the above. So I always say, at the worst, we’ll have a good lunch, and in a way that just takes the pressure off.

And the second thing I always say is, It’s just like algebra. A plus and a minus equals a minus. So if I love it and you don’t, then we keep working at it. If you love it and I don’t, we keep working at it, because when we both know it’s right then it’ll be right.

PB: Do you pass out what the roles will be? One does the lyrics…

JI: No. no. It’s organic. With someone like Bette, I don’t know that she plays — I had a guitar in my hand, but she certainly knows what feels good on her voice and she has such an encyclopaedic knowledge of songs and music in general that she was able to draw from sources that I wouldn’t normally be able to draw from; her history of show tunes, for instance.

With Sarah, she comes straight out of the jazz book, almost to the exclusion of anything else until this last year or so, and she’s also cutting her own album so she knows what feels good on her voice and I have to take that into consideration because it might not feel good on my voice.

So there’s a lot of things that go into co-writing, but the main thing that goes into it, I always say, is just a willing heart. You want to make each other shine. You’re not in competition.

PB: That’s a great attitude. Last year, you were an Audio Award nominee for ‘The Singer and the Song’. Emerging and gigging writers, vocalists and instrumentalists out there could gain a great deal from the content. You shared notes about “phrasing, interpretations and tunings.” Can you share some tips?

JI: I think when you set out to interpret someone else’s songs and make them your own, particularly when you’re sitting in an airless closet with just a guitar in your hand, one of the things you have to lose is your ego. It takes a lot of ego to be a good performer, but if you’re going to be a good interpreter or a good songwriter you can’t afford it. So you have to draw a clear line between yourself as a performer and yourself as those other things.

PB: On your website, you offer a download of ‘Danger Danger’ from ‘Folk is the New Black’. You suggest that it’s relevant today. Why?

JI: I think there are a lot of people right now with the attitude that anything that might make their children or themselves think differently is to be banned and, to me, anything that makes you think is a good thing. Period. End of discussion.

PB: One of your neighbours, I read, was Isaac Asimov.

JI: In New York. At 10 W. 66th. I will regret to my dying day that I never said anything to him. I saw him in the elevator all the time. He and Gene Simmons. Gene eventually looked at me and said, “It’s me, Gene.” I said, “Holy cow, that’s what you look like.”

PB: Do you think you picked up something in the air from those random Isaac Asimov encounters? Something that inspired your sci fi sensibilities?

JI: It was a building close to Lincoln Center that was affordable to artists.

PB: But at the time that you began writing science fiction, it wasn’t a discipline that was particularly accessible to female writers, was it?

JI: From what I understand…I started reading it when I was a kid. My dad used to tell us stories. He was a wonderful story teller and he would take a Ray Bradbury story, but he would tell it to us before we could read.

PB: In his own words?

JI: Yeah, he would paraphrase it. He read lots of the Oscar Wilde stories, Edgar Allan Poe, 'The Pit and the Pendulum', stuff like that. He would use them as short stories but talking them to us. And then I just started reading them as soon as I could read. And so I grew up in the form.

There were people like Leigh Brackett ('No Good from a Corpse') and others, but really, the women in science fiction didn’t have what I would call a solid footing, maybe, or the ability to write under their own names as opposed to using their initials until the mid 1970s when they started coming out with books like 'Women of Wonder'.

And then now, of course, you have people like Connie Willis ('The Doomsday Book', 'Blackout'), who are just at the very top of the heap and you have Anne McCaffrey ('Dragonriders of Pern'), who was the first female science fiction writer to hit the New York Times bestseller list and you don’t’ see the kind of gender disparity that you used to see. Although, it’s still there, I’m sure.

PB: You’ve written and inspired Mike Resnick and recently you narrated for him, didn’t you?

JI: I did his book 'Kirinyaga'. It’s kind of a very leftfield story of a Kenyan shaman, black male, being narrated by a Jewish, white girl. I think I said that when we first thought about it, I thought, ooh, I’m going to take a lot of flak, and then I thought, science fiction is an outsider genre to begin with, so why not? I love the book. It’s one of my favorite books on earth and I didn’t see anybody else jumping to do it, so I jumped in.

PB: And there you go, exploring creativity through narration, perhaps from listening to your dad and from the Stella Adler school of acting. All those skills coming to the fore.

JI: Yeah. The fun thing is using all of those parts of yourself.

PB: I was in the car with my sixteen-year-old. She pulled out her play list and I heard a warm, familiar voice introducing and then singing one of my favorite ballads, ‘At Seventeen’. The cool thing was that she discovered the song, not through me, but on her own.

JI: That’s great. That’s wonderful. It’s what every songwriter wants to hear.

PB: There’s that line, “inventing lovers on the phone” and, of course, now they’re all texting, but the theme for many of us is timeless. Do you still identify with the “brown-eyed girl in hand-me-downs”? Is the song as timeless to you as it is to us?

JI: Oh, yeah. First of all, because I don’t think anybody ever looks in the mirror all the time and says, “Dang, I look great.” I mean, none of us do that. And there’s always the unsureness, but I think also for me as the writer, it’s become such a powerful calling card. That’s what you wish for your work, that it go universal and that it cross generations. It’s pretty remarkable to watch that happening.

PB: I’ve heard men say, "Oh, my God, I was never picked for basketball." I relate. They don’t say, "Oh, that’s a girl song.”

JI: It was a great lesson to me that boys actually related to it. I would never have dreamed that when I wrote it.

PB: I remember reading about you setting on fire producer Shadow Morton’s newspaper. You were performing and he was ignoring you. Sometimes young artists feel marginalized by people in authority when they start their careers. You demonstrated a lot of confidence.

JI: There’s a big difference, though. Most artists will fight for their music. It’s very hard to fight for yourself in the other areas. That’s why it’s not good to negotiate for yourself and I think it goes back to the Sony deal. Part of the reason for the Sony deal was to take the load off me.

PB: And artists are called upon to do so much these days, beyond creating and performing.

JI: Think about your own life. If you think about your own life and the amount of time you put into work and now you also have to put that time in on your computer and on email and on a mobile phone and then texting and all of these other dozens of things. Then as an artist - the artist today is faced with having to put time in on Facebook, Twitter, on email, on their website and on these five hundred other things that have nothing to do with their work, so it becomes a bigger and bigger problem.

I’m becoming convinced that the Internet kills creativity because it’s such a time suck and it’s so not what any of us expected. We expected, wow, this will be cool, I can go see the Pyramids. Wow, this will be great. I can go see the British Royal Museum and instead everybody’s on Facebook.

PB: I remember going into a coffee shop and mingling. Now you can’t say hello to anyone…

JI: Nobody’s listening.

PB: The theme of ‘Society’s Child’ at the time of its release was considered controversial and was even banned. If you were to reimagine that song for this era, who would the major characters be?

JI: Probably a Christian and a Muslim. It could be so many things. It’s so unfortunate. It could still be a black and a white, which is really unfortunate. It could be a gay person in a straight family that are convinced they never met one. There are so many applications for the person you’re bringing home not being welcomed in your home. I think that’s one of the reasons that the song has endured.

PB: Yes, because we really need dialogue.

JI: That’s one of the cool things about that song that I’ve heard from so many people. One guy said, “I remember my mother’s weekly coffee group talking about that and hearing them say, ‘Well, yeah, but would you let your daughter date one?’” That really opened up discussions, which is great.

PB: You possess a wealth of knowledge and experience in the music industry. What would you say to a young person starting out?

JI: I would start with, trust your instincts, but listen to everyone and then I would say, trust no one and then I would probably say, I would have a day job and learn to budget and think of the future because the biggest thing I see with most artists is that there is no tomorrow and, fortunately if you stay alive long enough, there always is tomorrow.

PB: Imagine a film about your life. What would be the redeeming qualities of this film? Who would star as Janis Ian or be a co-star?

JI: Oh, gosh, why don’t we have Meryl Streep play me? Why not? I mean if we’re making up the whole thing anyway, or the woman who plays Crazy Eyes (actress Uza Aduba) on 'Orange is the New Black'. She’s a pretty phenomenal actor.

PB: Would it be a dystopic universe, since you’re so well-versed in that?

JI: I think right now it’s dystopic enough.

PB: What’s happening in Nashville these days?

JI: It’s very hot and we’re just finishing up our big Pride Festival, which was a huge success. We had En Vogue this year, so that was really rocking. We’re getting ready to head into full-blown tourist season, so that’s when everybody else stays home. And I’m having my annual July 4th party. It’s called the “No Networking Party”.

PB: Thank you.

Janis Ian's catalogue is available now on iTunes: www.smarturl.it/JanisIan. More information about Janis Ian can be found at www.janisian.com

Band Links:-

https://www.janisian.com/

https://en-gb.facebook.com/janisianpag

https://twitter.com/therealjanisian

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Janis_Ia

Have a Listen:-

Picture Gallery:-